Lord Minto and the Indian Nationalist Movement, with Special Reference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeking Offense: Censorship and the Constitution of Democratic Politics in India

SEEKING OFFENSE: CENSORSHIP AND THE CONSTITUTION OF DEMOCRATIC POLITICS IN INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Ameya Shivdas Balsekar August 2009 © 2009 Ameya Shivdas Balsekar SEEKING OFFENSE: CENSORSHIP AND THE CONSTITUTION OF DEMOCRATIC POLITICS IN INDIA Ameya Shivdas Balsekar, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 Commentators have frequently suggested that India is going through an “age of intolerance” as writers, artists, filmmakers, scholars and journalists among others have been targeted by institutions of the state as well as political parties and interest groups for hurting the sentiments of some section of Indian society. However, this age of intolerance has coincided with a period that has also been characterized by the “deepening” of Indian democracy, as previously subordinated groups have begun to participate more actively and substantively in democratic politics. This project is an attempt to understand the reasons for the persistence of illiberalism in Indian politics, particularly as manifest in censorship practices. It argues that one of the reasons why censorship has persisted in India is that having the “right to censor” has come be established in the Indian constitutional order’s negotiation of multiculturalism as a symbol of a cultural group’s substantive political empowerment. This feature of the Indian constitutional order has made the strategy of “seeking offense” readily available to India’s politicians, who understand it to be an efficacious way to discredit their competitors’ claims of group representativeness within the context of democratic identity politics. -

J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J ~

I j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j ~ . he ~ Ra,;t -.se~~\trr) ObananJayarao Gadgtl Library mmm~ m~ mmlillllllllmal GIPE·PUNE"()64S06 - To Dadabhai -Naotoji, Esquire, j j j j j j j j j j j j j 'V2 M45 j x j j j :D~ j j 64 gO' j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j PREPACk TH B Honourable Sir Pherozeshah" Merwanjee Mehta, K.C.I.B., M.A., Barrister-at-Iaw, occupies a fore most position among the worthiest of our public men by reason alike of commanding talents and disinterested patriotism. His speeches and writings, which have al ways attracted considerable attention, are admired no less for their literary charm than for the soundness of his opinions,-closely argued, expressed in earnest lang uage and breathing conviction in every syllable. Sir Pherozeshah's public life began so early as in 1867, and during the long space of time that has elapsed since then there has not been any important problem, local, provincial or imperial, in the discussion of which he has not taken a conspicuous part. What a large part he has played in the p1,lblic life of his city, province and country, is evident from his many speeches as well as his varied and numerous contributions to the fress; which are now presented to the world in this volume. It would be presumption on my part to pass an opinion on the character of Sir Pheroze shah's pronouncements on public questions. -

* RPO Guwahati Covers Five Other North-Eastern States Also at Present

* RPO Guwahati covers five other North-Eastern States also at present. **RPO Chandigarh covers parts of Punjab and Haryana. ***RPO Delhi covers parts of Haryana. @RPO Kolkata covers Sikkim and Tripura. ANNEXURE-III STATE-WISE LIST OF POST OFFICE PASSPORT SEVA KENDRAS (POPSKs) S.No. Locations State/UT Passport Office 1 Anantpur Andhra Pradesh Vijayawada 2 Bapatla Andhra Pradesh Vijayawada 3 Chittoor Andhra Pradesh Vijayawada 4 Gudivada Andhra Pradesh Vijayawada 5 Guntur Andhra Pradesh Vijayawada 6 Hindupur Andhra Pradesh Vijayawada 7 Kadappa Andhra Pradesh Vijayawada 8 Kodur Andhra Pradesh Vijayawada 9 Kurnool Andhra Pradesh Vijayawada 10 Nandyal Andhra Pradesh Vijayawada 11 Narasaraopet Andhra Pradesh Vijayawada 12 Nellore Andhra Pradesh Vijayawada 13 Ongole Andhra Pradesh Vijayawada 14 Amalapuram Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatnam 15 Eluru Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatnam 16 Kakinada Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatnam 17 Rajamundry Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatnam 18 Srikakulam Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatnam 19 Vizianagaram Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatnam 20 Yelamanchili Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatnam 21 Changlang Arunachal Pradesh Guwahati 22 Khonsa Arunachal Pradesh Guwahati 23 Barpeta Assam Guwahati 24 Dhubri Assam Guwahati 25 Dibrugarh Assam Guwahati 26 Goalpara Assam Guwahati 27 Golaghat Assam Guwahati 28 Jorhat Assam Guwahati 29 Karbi Anglong Assam Guwahati 30 Karimganj Assam Guwahati 31 Kokrajhar Assam Guwahati 32 Mangaldoi Assam Guwahati 33 Nawgong Assam Guwahati 34 North Lakhimpur Assam Guwahati 35 Silchar Assam Guwahati 36 Tezpur Assam Guwahati 37 Tinsukia -

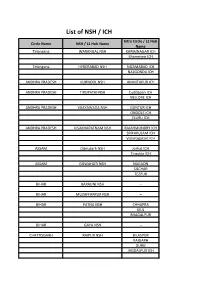

List of NSH / ICH Intra Circle / L2 Hub Circle Name NSH / L1 Hub Name Name Telangana WARANGAL NSH KARIMNAGAR ICH Khammam ICH

List of NSH / ICH Intra Circle / L2 Hub Circle Name NSH / L1 Hub Name Name Telangana WARANGAL NSH KARIMNAGAR ICH Khammam ICH Telangana HYDERABAD NSH NIZAMABAD ICH NALGONDA ICH ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL NSH ANANTAPUR ICH ANDHRA PRADESH TIRUPATHI NSH Cuddapah ICH NELLORE ICH ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA NSH GUNTUR ICH ONGOLE ICH ELURU ICH ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM NSH RAJAHMUNDRY ICH SRIKAKULAM ICH Vizianagaram ICH ASSAM Dibrugarh NSH Jorhat ICH Tinsukia ICH ASSAM GUWAHATI NSH NAGAON SILCHAR TEZPUR BIHAR BARAUNI NSH – BIHAR MUZAFFARPUR NSH – BIHAR PATNA NSH CHHAPRA KIUL BHAGALPUR BIHAR GAYA NSH – CHATTISGARH RAIPUR NSH BILASPUR RAIGARH DURG JAGDALPUR ICH DELHI DELHI NSH – GUJRAT AHMEDABAD NSH HIMATNAGAR MEHSANA PALANPUR BHAVNAGAR BHUJ Dhola ICH GUJRAT RAJKOT NSH JAMNAGAR JUNAGADH SURENDRANAGAR GUJRAT SURAT NSH VALSAD GUJRAT VADODARA NSH BHARUCH GODHARA ANAND HARYANA GURGAON NSH FARIDABAD ICH REWARI ICH HARYANA KARNAL NSH – HARYANA ROHTAK NSH HISAR ICH HARYANA AMBALA NSH SOLAN MANDI HIMACHAL PRADESH SHIMLA NSH SOLAN ICH HIMACHAL PRADESH PATHANKOT NSH KANGRA HAMIRPUR JAMMUKASHMIR JAMMU NSH – JAMMUKASHMIR SRINAGAR NSH – JHARKHAND JAMSHEDPUR NSH JHARKHAND RANCHI NSH DALTONGANJ HAZARIBAGH ROAD JHARKHAND DHANBAD NSH B. DEOGHAR KARNATAKA BENGALURU NSH BALLARI ICH TUMAKURU ICH KARNATAKA BELAGAVI NSH – KARNATAKA KALABURAGI NSH RAICHUR ICH KARNATAKA HUBBALLI-DHARWAD NSH BAGALKOT ICH KUMTA ICH VIJAYAPURA ICH KARNATAKA MANGALURU NSH – KARNATAKA MYSURU NSH – KARNATAKA ARSIKERE NSH – KERALA KOCHI NSH Kottayam ICH KERALA THRISSUR PALAKKAD ICH KERALA TRIVANDRUM -

Angeli, Helen Rossetti, Collector Angeli-Dennis Collection Ca.1803-1964 4 M of Textual Records

Helen (Rossetti) Angeli - Imogene Dennis Collection An inventory of the papers of the Rossetti family including Christina G. Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Michael Rossetti, as well as other persons who had a literary or personal connection with the Rossetti family In The Library of the University of British Columbia Special Collections Division Prepared by : George Brandak, September 1975 Jenn Roberts, June 2001 GENEOLOGICAL cw_T__O- THE ROssFTTl FAMILY Gaetano Polidori Dr . John Charlotte Frances Eliza Gabriele Rossetti Polidori Mary Lavinia Gabriele Charles Dante Rossetti Christina G. William M . Rossetti Maria Francesca (Dante Gabriel Rossetti) Rossetti Rossetti (did not marry) (did not marry) tr Elizabeth Bissal Lucy Madox Brown - Father. - Ford Madox Brown) i Brother - Oliver Madox Brown) Olive (Agresti) Helen (Angeli) Mary Arthur O l., v o-. Imogene Dennis Edward Dennis Table of Contents Collection Description . 1 Series Descriptions . .2 William Michael Rossetti . 2 Diaries . ...5 Manuscripts . .6 Financial Records . .7 Subject Files . ..7 Letters . 9 Miscellany . .15 Printed Material . 1 6 Christina Rossetti . .2 Manuscripts . .16 Letters . 16 Financial Records . .17 Interviews . ..17 Memorabilia . .17 Printed Material . 1 7 Dante Gabriel Rossetti . 2 Manuscripts . .17 Letters . 17 Notes . 24 Subject Files . .24 Documents . 25 Printed Material . 25 Miscellany . 25 Maria Francesca Rossetti . .. 2 Manuscripts . ...25 Letters . ... 26 Documents . 26 Miscellany . .... .26 Frances Mary Lavinia Rossetti . 2 Diaries . .26 Manuscripts . .26 Letters . 26 Financial Records . ..27 Memorabilia . .. 27 Miscellany . .27 Rossetti, Lucy Madox (Brown) . .2 Letters . 27 Notes . 28 Documents . 28 Rossetti, Antonio . .. 2 Letters . .. 28 Rossetti, Isabella Pietrocola (Cole) . ... 3 Letters . ... 28 Rossetti, Mary . .. 3 Letters . .. 29 Agresti, Olivia (Rossetti) . -

Legislative Council Proceedings and Debates Held by SAMP September 2007

SAMP Holdings List – Legislative Council Debates South Asia Microform Project September 2007 Legislative Council Proceedings and Debates Held by SAMP September 2007 Contents: India. Imperial Legislative Council. .............................................................................................................................. 1 Assam (India). .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Bengal (India). ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 Bihar and Orissa (India). ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Bihar (India). ................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Bombay (India : State). .................................................................................................................................................. 7 Burma. .......................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Central Provinces and Berar (India). ........................................................................................................................... -

Modern Indian Political Thought Ii Modern Indian Political Thought Modern Indian Political Thought Text and Context

Modern Indian Political Thought ii Modern Indian Political Thought Modern Indian Political Thought Text and Context Bidyut Chakrabarty Rajendra Kumar Pandey Copyright © Bidyut Chakrabarty and Rajendra Kumar Pandey, 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. First published in 2009 by SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd B1/I-1 Mohan Cooperative Industrial Area Mathura Road, New Delhi 110 044, India www.sagepub.in SAGE Publications Inc 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, California 91320, USA SAGE Publications Ltd 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP, United Kingdom SAGE Publications Asia-Pacifi c Pte Ltd 33 Pekin Street #02-01 Far East Square Singapore 048763 Published by Vivek Mehra for SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd, typeset in 10/12 pt Palatino by Star Compugraphics Private Limited, Delhi and printed at Chaman Enterprises, New Delhi. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chakrabarty, Bidyut, 1958– Modern Indian political thought: text and context/Bidyut Chakrabarty, Rajendra Kumar Pandey. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Political science—India—Philosophy. 2. Nationalism—India. 3. Self- determination, National—India. 4. Great Britain—Colonies—India. 5. India— Colonisation. 6. India—Politics and government—1919–1947. 7. India— Politics and government—1947– 8. India—Politics and government— 21st century. I. Pandey, Rajendra Kumar. II. Title. JA84.I4C47 320.0954—dc22 2009 2009025084 ISBN: 978-81-321-0225-0 (PB) The SAGE Team: Reema Singhal, Vikas Jain, Sanjeev Kumar Sharma and Trinankur Banerjee To our parents who introduced us to the world of learning vi Modern Indian Political Thought Contents Preface xiii Introduction xv PART I: REVISITING THE TEXTS 1. -

Contributions of Lala Har Dayal As an Intellectual and Revolutionary

CONTRIBUTIONS OF LALA HAR DAYAL AS AN INTELLECTUAL AND REVOLUTIONARY ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF ^ntiat ai pijtl000pi{g IN }^ ^ HISTORY By MATT GAOR CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2007 ,,» '*^d<*'/. ' ABSTRACT India owes to Lala Har Dayal a great debt of gratitude. What he did intotality to his mother country is yet to be acknowledged properly. The paradox ridden Har Dayal - a moody idealist, intellectual, who felt an almost mystical empathy with the masses in India and America. He kept the National Independence flame burning not only in India but outside too. In 1905 he went to England for Academic pursuits. But after few years he had leave England for his revolutionary activities. He stayed in America and other European countries for 25 years and finally returned to England where he wrote three books. Har Dayal's stature was so great that its very difficult to put him under one mould. He was visionary who all through his life devoted to Boddhi sattava doctrine, rational interpretation of religions and sharing his erudite knowledge for the development of self culture. The proposed thesis seeks to examine the purpose of his returning to intellectual pursuits in England. Simultaneously the thesis also analyses the contemporary relevance of his works which had a common thread of humanism, rationalism and scientific temper. Relevance for his ideas is still alive as it was 50 years ago. He was true a patriotic who dreamed independence for his country. He was pioneer for developing science in laymen and scientific temper among youths. -

Places in London Associated with Indian Freedom Fighters

A SPECIAL TOUR OF PLACES IN LONDON ASSOCIATED WITH INDIAN FREEDOM FIGHTERS by V S Godbole 1 Preface Indian Freedom struggle went through four phases as described in the next few pages. The role of the revolutionaries has been wiped out of memory by various parties of vested interest. However, because of their sacrifices we have become independent. We now see increased prosperity in India and as a result, many Indians are now visiting England, Europe and even America. Some go around on world tour. And they are not all businessmen. The visitors even include school teachers, and draughtsmen who were once regarded as poorly paid. It is appropriate therefore that they should visit places associated with Veer Savarkar and other Indian freedom fighters who made today's changed circumstances possible. After the failure of the 1857 war to gain Indian independence from rule of the East India Company, some one said to Emperor Bahadurshah, Dum Dumaye Dam Nahi Aba Khaira Mango Janaki Aih, Jafar Aba Thandi Hui Samsher Hindostanki The valour of Indian people has now subsided. You better beg the English for your life. Bahadurshah replied Gaziame Boo Rahegi Jabtalak Eemanki Tabtak To London tak Chalegi Teg Hindostanki As long as there is a spark of self respect in the blood of our youth, we will carry our fight for independence even to doors of London. That fight was indeed carried in London 50 years later by Savarkar and others. Those patriots sacrificed their careers, their comfort, and their lives so that the future generations would live with dignity. -

INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 1885-1947 Year Place President

INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 1885-1947 Year Place President 1885 Bombay W.C. Bannerji 1886 Calcutta Dadabhai Naoroji 1887 Madras Syed Badruddin Tyabji 1888 Allahabad George Yule First English president 1889 Bombay Sir William 1890 Calcutta Sir Pherozeshah Mehta 1891 Nagupur P. Anandacharlu 1892 Allahabad W C Bannerji 1893 Lahore Dadabhai Naoroji 1894 Madras Alfred Webb 1895 Poona Surendranath Banerji 1896 Calcutta M Rahimtullah Sayani 1897 Amraoti C Sankaran Nair 1898 Madras Anandamohan Bose 1899 Lucknow Romesh Chandra Dutt 1900 Lahore N G Chandravarkar 1901 Calcutta E Dinsha Wacha 1902 Ahmedabad Surendranath Banerji 1903 Madras Lalmohan Ghosh 1904 Bombay Sir Henry Cotton 1905 Banaras G K Gokhale 1906 Calcutta Dadabhai Naoroji 1907 Surat Rashbehari Ghosh 1908 Madras Rashbehari Ghosh 1909 Lahore Madanmohan Malaviya 1910 Allahabad Sir William Wedderburn 1911 Calcutta Bishan Narayan Dhar 1912 Patna R N Mudhalkar 1913 Karachi Syed Mahomed Bahadur 1914 Madras Bhupendranath Bose 1915 Bombay Sir S P Sinha 1916 Lucknow A C Majumdar 1917 Calcutta Mrs. Annie Besant 1918 Bombay Syed Hassan Imam 1918 Delhi Madanmohan Malaviya 1919 Amritsar Motilal Nehru www.bankersadda.com | www.sscadda.com| www.careerpower.in | www.careeradda.co.inPage 1 1920 Calcutta Lala Lajpat Rai 1920 Nagpur C Vijaya Raghavachariyar 1921 Ahmedabad Hakim Ajmal Khan 1922 Gaya C R Das 1923 Delhi Abul Kalam Azad 1923 Coconada Maulana Muhammad Ali 1924 Belgaon Mahatma Gandhi 1925 Cawnpore Mrs.Sarojini Naidu 1926 Guwahati Srinivas Ayanagar 1927 Madras M A Ansari 1928 Calcutta Motilal Nehru 1929 Lahore Jawaharlal Nehru 1930 No session J L Nehru continued 1931 Karachi Vallabhbhai Patel 1932 Delhi R D Amritlal 1933 Calcutta Mrs. -

Mundella Papers Scope

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 6 - 9, MS 22 Title: Mundella Papers Scope: The correspondence and other papers of Anthony John Mundella, Liberal M.P. for Sheffield, including other related correspondence, 1861 to 1932. Dates: 1861-1932 (also Leader Family correspondence 1848-1890) Level: Fonds Extent: 23 boxes Name of creator: Anthony John Mundella Administrative / biographical history: The content of the papers is mainly political, and consists largely of the correspondence of Mundella, a prominent Liberal M.P. of the later 19th century who attained Cabinet rank. Also included in the collection are letters, not involving Mundella, of the family of Robert Leader, acquired by Mundella’s daughter Maria Theresa who intended to write a biography of her father, and transcriptions by Maria Theresa of correspondence between Mundella and Robert Leader, John Daniel Leader and another Sheffield Liberal M.P., Henry Joseph Wilson. The collection does not include any of the business archives of Hine and Mundella. Anthony John Mundella (1825-1897) was born in Leicester of an Italian father and an English mother. After education at a National School he entered the hosiery trade, ultimately becoming a partner in the firm of Hine and Mundella of Nottingham. He became active in the political life of Nottingham, and after giving a series of public lectures in Sheffield was invited to contest the seat in the General Election of 1868. Mundella was Liberal M.P. for Sheffield from 1868 to 1885, and for the Brightside division of the Borough from November 1885 to his death in 1897. -

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India Gyanendra Pandey CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Remembering Partition Violence, Nationalism and History in India Through an investigation of the violence that marked the partition of British India in 1947, this book analyses questions of history and mem- ory, the nationalisation of populations and their pasts, and the ways in which violent events are remembered (or forgotten) in order to en- sure the unity of the collective subject – community or nation. Stressing the continuous entanglement of ‘event’ and ‘interpretation’, the author emphasises both the enormity of the violence of 1947 and its shifting meanings and contours. The book provides a sustained critique of the procedures of history-writing and nationalist myth-making on the ques- tion of violence, and examines how local forms of sociality are consti- tuted and reconstituted by the experience and representation of violent events. It concludes with a comment on the different kinds of political community that may still be imagined even in the wake of Partition and events like it. GYANENDRA PANDEY is Professor of Anthropology and History at Johns Hopkins University. He was a founder member of the Subaltern Studies group and is the author of many publications including The Con- struction of Communalism in Colonial North India (1990) and, as editor, Hindus and Others: the Question of Identity in India Today (1993). This page intentionally left blank Contemporary South Asia 7 Editorial board Jan Breman, G.P. Hawthorn, Ayesha Jalal, Patricia Jeffery, Atul Kohli Contemporary South Asia has been established to publish books on the politics, society and culture of South Asia since 1947.