Changing Patterns of the Professionalpolitician

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Catch and Trade of Seahorses in the Philippines Post-CITES

ISSN 1198-6727 Fisheries Centre Research Reports 2019 Volume 27 Number 2 The catch and trade of seahorses in the Philippines post-CITES Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, The University of British Columbia, Canada The catch and trade of seahorses in the Philippines post-CITES Project Seahorse and the Zoological Society of London-Philippines A report on research carried out in collaboration with the Philippines Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Please cite as: Foster, S.J., Stanton, L.M., Nellas, A.C., Arias, M.M. and Vincent, A.C.J. (2019). The catch and trade of seahorses in the Philippines post-CITES. Fisheries Centre Research Reports 27(2): 45pp. © Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, The University of British Columbia, 2019 Fisheries Centre Research Reports are Open Access publications ISSN 1198-6727 Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries The University of British Columbia 2202 Main Mall Vancouver, B.C., Canada V6T 1Z4 This research report is indexed in Google Scholar, ResearchGate, the UBC library archive (cIRcle). 2019 Fisheries Centre Research Report 27 (2) Table of Contents Director’s Foreword ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Abstract .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. -

Directory of Participants 11Th CBMS National Conference

Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Academe Dr. Tereso Tullao, Jr. Director-DLSU-AKI Dr. Marideth Bravo De La Salle University-AKI Associate Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 Ms. Nelca Leila Villarin E-Mail: [email protected] Social Action Minister for Adult Formation and Advocacy De La Salle Zobel School Mr. Gladstone Cuarteros Tel No: (02) 771-3579 LJPC National Coordinator E-Mail: [email protected] De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 7212000 local 608 Fax: 7248411 E-Mail: [email protected] Batangas Ms. Reanrose Dragon Mr. Warren Joseph Dollente CIO National Programs Coordinator De La Salle- Lipa De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 756-5555 loc 317 Fax: 757-3083 Tel No: 7212000 loc. 611 Fax: 7260946 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Camarines Sur Brother Jose Mari Jimenez President and Sector Leader Mr. Albino Morino De La Salle Philippines DEPED DISTRICT SUPERVISOR DEPED-Caramoan, Camarines Sur E-Mail: [email protected] Dr. Dina Magnaye Assistant Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Cavite Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 E-Mail: [email protected] Page 1 of 78 Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Ms. Rosario Pareja Mr. Edward Balinario Faculty De La Salle University-Dasmarinas Tel No: 046-481-1900 Fax: 046-481-1939 E-Mail: [email protected] Mr. -

Binanog Dance

Gluck Classroom Fellow: Jemuel Jr. Barrera-Garcia Ph.D. Student in Critical Dance Studies: Designated Emphasis in Southeast Asian Studies Flying Without Wings: The Philippines’ Binanog Dance Binanog is an indigenous dance from the Philippines that features the movement of an eagle/hawk to the symbolic beating of bamboo and gong that synchronizes the pulsating movements of the feet and the hands of the lead and follow dancers. This specific type of Binanog dance comes from the Panay-Bukidnon indigenous community in Panay Island, Western Visayas, Philippines. The Panay Bukidnon, also known as Suludnon, Tumandok or Panayanon Sulud is usually the identified indigenous group associated with the region and whose territory cover the mountains connecting the provinces of Iloilo, Capiz and Aklan in the island of Panay, one of the main Visayan islands of the Philippines. Aside from the Aetas living in Aklan and Capiz, this indigenous group is known to be the only ethnic Visayan language-speaking community in Western Visayas. SMILE. A pair of Binanog dancers take a pose They were once associated culturally as speakers after a performance in a public space. of the island’s languages namely Kinaray-a, Akeanon and Hiligaynon, most speakers of which reside in the lowlands of Panay and their geographical remoteness from Spanish conquest, the US invasion of the country, and the hairline exposure they had with the Japanese attacks resulted in a continuation of a pre-Hispanic culture and tradition. The Suludnon is believed to have descended from the migrating Indonesians coming from Mainland Asia. The women have developed a passion for beauty wearing jewelry made from Spanish coins strung together called biningkit, a waistband of coins called a wakus, and a headdress of coins known as a pundong. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized CDD and Social Capital Impact Designing a Baseline Survey in the Philippines Copyright © 2005 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C., 20433, USA All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America First Printing May 2005 This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, http://www.copyright.com/. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202-522-2422, and e-mail [email protected]. -

MAKING the LINK in the PHILIPPINES Population, Health, and the Environment

MAKING THE LINK IN THE PHILIPPINES Population, Health, and the Environment The interconnected problems related to population, are also disappearing as a result of the loss of the country’s health, and the environment are among the Philippines’ forests and the destruction of its coral reefs. Although greatest challenges in achieving national development gross national income per capita is higher than the aver- goals. Although the Philippines has abundant natural age in the region, around one-quarter of Philippine fami- resources, these resources are compromised by a number lies live below the poverty threshold, reflecting broad social of factors, including population pressures and poverty. The inequity and other social challenges. result: Public health, well-being and sustainable develop- This wallchart provides information and data on crit- ment are at risk. Cities are becoming more crowded and ical population, health, and environmental issues in the polluted, and the reliability of food and water supplies is Philippines. Examining these data, understanding their more uncertain than a generation ago. The productivity of interactions, and designing strategies that take into the country’s agricultural lands and fisheries is declining account these relationships can help to improve people’s as these areas become increasingly degraded and pushed lives while preserving the natural resource base that pro- beyond their production capacity. Plant and animal species vides for their livelihood and health. Population Reference Bureau 1875 Connecticut Ave., NW, Suite 520 Washington, DC 20009 USA Mangroves Help Sustain Human Vulnerability Coastal Communities to Natural Hazards Comprising more than 7,000 islands, the Philippines has an extensive coastline that is a is Increasing critical environmental and economic resource for the nation. -

Supplementary Document 6: Typhoon Yolanda-Affected Areas and Areas Covered by the Kalahi– Cidss National Community-Driven Development Project

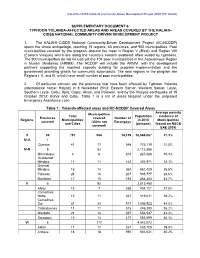

KALAHI–CIDSS National Community-Driven Development Project (RRP PHI 46420) SUPPLEMENTARY DOCUMENT 6: TYPHOON YOLANDA-AFFECTED AREAS AND AREAS COVERED BY THE KALAHI– CIDSS NATIONAL COMMUNITY-DRIVEN DEVELOPMENT PROJECT 1. The KALAHI–CIDDS National Community-Driven Development Project (KC-NCDDP) spans the whole archipelago, reaching 15 regions, 63 provinces, and 900 municipalities. Poor municipalities covered by the program abound the most in Region V (Bicol) and Region VIII (Eastern Visayas) which are along the country’s eastern seaboard often visited by typhoons. The 900 municipalities do not include yet the 104 poor municipalities in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM). The NCDDP will include the ARMM, with the development partners supporting the required capacity building for program implementation and the government providing grants for community subprojects. The new regions in the program are Regions I, II, and III, which have small number of poor municipalities. 2. Of particular concern are the provinces that have been affected by Typhoon Yolanda (international name: Haiyan) in 8 November 2013: Eastern Samar, Western Samar, Leyte, Southern Leyte, Cebu, Iloilo, Capiz, Aklan, and Palawan, and by the Visayas earthquake of 15 October 2013: Bohol and Cebu. Table 1 is a list of areas targeted under the proposed Emergency Assistance Loan. Table 1: Yolanda-affected areas and KC-NCDDP Covered Areas Average poverty Municipalities Total Population incidence of Provinces covered Number of Regions Municipalities in 2010 Municipalities -

STATE of the COASTS the Second of Guimaras Province

The Second STATE OF THE COASTS of Guimaras Province The Provincial Government of Guimaras, Philippines The Second State of the Coasts of Guimaras Province The Provincial Government of Guimaras, Philippines The Second State of the Coasts of Guimaras Province November 2018 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes or to provide wider dissemination for public response, provided prior written permission is obtained from the PEMSEA Resource Facility Executive Director, acknowledgment of the source is made and no commercial usage or sale of the material occurs. PEMSEA would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any purpose other than those given above without a written agreement between PEMSEA and the requesting party. Published by the Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA) and Provincial Government of Guimaras, Philippines with support from the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Printed in Quezon City, Philippines Citation: PEMSEA and Provincial Government of Guimaras, Philippines. 2018. The Second State of the Coasts of Guimaras Province. Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA), Quezon City, Philippines. ISBN 978-971-812-048-4 PEMSEA is an international organization mandated to implement the Sustainable Development Strategy for the Seas of East Asia (SDS-SEA). The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of PEMSEA and other participating organizations. The designation employed and the presentation do not imply expression of opinion, whatsoever on the part of PEMSEA concerning the legal status of any country or territory, or its authority or concerningthe delimitation of its boundaries. -

Iloilo Antique Negros Occidental Capiz Aklan Guimaras

Sigma Kalibo Panitan Makato Handicap International Caluya PRCS - IFRC Don Bosco Network Ivisan PRCS - IFRC Humanity First Tangalan CapizNED CapizNED Don Bosco Network PRCS - IFRC CARE Supporting Self Recovery PRAY PRCS - IFRC IOM Citizens’ Disaster Response Center New Washington CapizNED IOM Region VI Humanity First Caritas Austria Don Bosco Network PRAY PRAY of Shelter Activities Malay PRAY World Vision Numancia PRCS - IFRC Humanity First PRCS - IFRC Buruanga IOM PRCS - IFRC by Municipality (Roxas) PRCS - IFRC Nabas Buruanga Don Boxco Network Balasan Pontevedra Altavas Roxas City PRCS - IFRC Ibajay HEKS - TFM 3W map summary Nabas Libertad IOM Region VI Caritas Austria IOM R e gion VI World Vision PRCS - IFRC CapizNED Tangalan CapizNED World Vision Citizens’ Disaster Response Center Produced April 14, 2014 Pandan PRAY Batad Numancia Don Bosco Network IOM Region VI CARE IRC Makato PRCS - IFRC PRCS - IFRC Malinao Makato Kalibo Panay MSF-CH Don BoSco Network Batan Humanity First Humanity First This map depicts data PRCS - IFRC Lezo IOM Caritas Austria Relief o peration for Northern Iloilo World Vision Lezo PRCS - IFRC CapizNED Solidar Suisse gathered by the Shelter CARE PRCS - IFRCNew Washington IOM Region VI Pilar Cluster about agencies Don Bosco Network HEKS - TFM Malinao HEKS - TFM Carles who are responding to Sebaste Banga Caritas Austria IOM Region VI PRAY DFID - HMS Illustrious Sebaste World Vision Welt Hunger Hilfe Typhoon Yolanda. PRCS - IFRC Concern Worldwide IOM Banga Citizens’ Disaster Response CenterRoxas City Humanity First IOM Region VI Batan Humanity First MSF-CH Carles Any agency listed may Citizens’Panay Disaster Response Center Save the Children Region VI Altavas Ivisan ADRA Ayala Land have projects at different Madalag AklanBalete SapSapi-Ani-An stages of completion (e.g. -

Province: Capiz Population (As of August 1, 2015; in Thousand): 2,384 Income Classification: 1St Class Province Major Economic Activities: Farming and Fishing

CAPIZ Mineral Profile I. GENERAL INFORMATION Region: WESTERN VISAYAS (Region VI) Province: Capiz Population (as of August 1, 2015; in thousand): 2,384 Income classification: 1st Class Province Major economic activities: Farming and fishing The Province of Capiz is located at the northeastern portion of Panay Island, bordering Aklan and Antique to the west and Iloilo to the South. Capiz faces the Sibuyan Sea to the North. Capiz is composed of one component city known as its capital, 16 municipalities, further subdivided into 590 barangays. II. LAND AREA AND MINERAL POTENTIAL Total land area of the province of Capiz is 263,371 hectares. The total area covered by the approved mining rights is only 2.24% or 5,888.0115 hectares of the total land area of Capiz. MINERAL PROFILE PROVINCE OF CAPIZ 1 Number of Mining Rights Issued by National Government in Capiz TYPE OF MINING RIGHT NUMBER AREA Mineral Production Sharing 2 5,888.0115 Agreements (MPSA) has. III. MINERAL RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS The province has no operating mining company. All mining companies are under exploration. Teresa Marble Corporation (MPSA No. 107-98-VI) and Quarry Ventures Philippines (MPSA No. 129-98-VI) explore minerals like copper and gold. MINERAL PROFILE PROVINCE OF CAPIZ 2 IV. ECONOMIC CONTRIBUTION Gross Regional Domestic Product (GRDP) As shown in the table below, the three major industries dominating the economic activities of Region VI in 2015 are agriculture and forestry which amounted to PhP 48,402,142 or 15.91%; other services (accommodation and food services, arts, entertainment and recreation services, etc) amounting to PhP 41,647,508 or 13.69%; and trade and repair of motor vehicles, motorcycle, personal and household goods amounting PhP 40,399,033 or 13.28%. -

CBD Fourth National Report

ASSESSING PROGRESS TOWARDS THE 2010 BIODIVERSITY TARGET: The 4th National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity Republic of the Philippines 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables 3 List of Figures 3 List of Boxes 4 List of Acronyms 5 Executive Summary 10 Introduction 12 Chapter 1 Overview of Status, Trends and Threats 14 1.1 Forest and Mountain Biodiversity 15 1.2 Agricultural Biodiversity 28 1.3 Inland Waters Biodiversity 34 1.4 Coastal, Marine and Island Biodiversity 45 1.5 Cross-cutting Issues 56 Chapter 2 Status of National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) 68 Chapter 3 Sectoral and cross-sectoral integration and mainstreaming of 77 biodiversity considerations Chapter 4 Conclusions: Progress towards the 2010 target and implementation of 92 the Strategic Plan References 97 Philippines Facts and Figures 108 2 LIST OF TABLES 1 List of threatened Philippine fauna and their categories (DAO 2004 -15) 2 Summary of number of threatened Philippine plants per category (DAO 2007 -01) 3 Invasive alien species in the Philippines 4 Jatropha estates 5 Number of forestry programs and forest management holders 6 Approved CADTs/CALTs as of December 2008 7 Number of documented accessions per crop 8 Number of classified water bodies 9 List of conservation and research priority areas for inland waters 10 Priority rivers showing changes in BOD levels 2003-2005 11 Priority river basins in the Philippines 12 Swamps/marshes in the Philippines 13 Trend of hard coral cover, fish abundance and biomass by biogeographic region 14 Quantity -

Iloilo Capiz Antique Aklan Negros Occidental

PHILIPPINES: Summary of Planned Cash Activities in REGION VI (Western Visayas) (as of 24 Feb 2014) Malay Planned Cash Activities 0 Buruanga Nabas 1 - 5 6 - 10 11 - 20 Libertad Ibajay Aklan > 20 Pandan Tangalan Numancia Makato Kalibo Lezo New Washington Malinao Banga Capiz Sebaste Roxas City Batan Panay Carles Balete Altavas Ivisan Sapi-An Madalag Pilar Balasan Estancia Panitan Mambusao Sigma Culasi Libacao Pontevedra President Roxas Batad Dao Jamindan Ma-Ayon San Dionisio Cuartero Tibiao Dumalag Sara Barbaza Tapaz Antique Dumarao Lemery Concepcion Bingawan Passi City Laua-An Calinog San Rafael Ajuy Lambunao San Enrique Bugasong Barotac Viejo Duenas Banate Negros Valderrama Dingle Occidental Janiuay Anilao Badiangan Mina Pototan Patnongon Maasin Iloilo Manapla Barotac Nuevo San Remigio Cadiz City Alimodian Cabatuan Sagay City New Lucena Victorias City Leon Enrique B. Magalona ¯ Belison Dumangas Zarraga Data Source: OCHA 3W database, Humanitarian Cluster lead organizations, GADMTubungan Santa Barbara Created 14 March 2014 San Jose Sibalom Silay City Escalante City 0 3 6 12 Km Planned Cash Activities in Region VI by Province, Municipality and Type of Activity as of 24 February 2014 Cash Grant/ Cash Grant/ Cash for Work Province Municipality Cash Voucher Transfer TOTAL (CFW) (conditional) (unconditional) BALETE 0 5 0 0 5 IBAJAY 0 0 0 1 1 AKLAN LIBACAO 0 1 0 0 1 MALINAO 0 8 0 1 9 BARBAZA 0 0 0 1 1 CULASI 0 0 0 1 1 LAUA-AN 0 0 0 1 1 ANTIQUE SEBASTE 0 0 0 1 1 TIBIAO 0 0 0 1 1 not specified 0 1 0 0 1 CUARTERO 0 0 0 1 1 DAO 0 6 0 0 6 JAMINDAN -

Aklan Antique Capiz Guimaras Iloilo Masbate Negros Occidental Negros

121°50'E 122°0'E 122°10'E 122°20'E 122°30'E 122°40'E 122°50'E 123°0'E 123°10'E 123°20'E Busay Tonga Salvacion Panubigan Panguiranan Lanas Poblacion Mapitogo Romblon Palane Mapili Pinamihagan Poblacion Jangan Ilaya Victory Masbate Dao Balud Baybay Sampad 12°0'N 12°0'N Yapak Ubo San Balabag Antonio San Andres Quinayangan Diotay Quinayangan Tonga Manoc-Manoc Guinbanwahan Mabuhay Bongcanaway Danao Union Pulanduta Caticlan Argao Rizal Calumpang Cubay San Norte Viray Unidos Poblacion Cogon Pawa Naasug Motag Balusbus Cubay Libertad Dumlog Sur Malay Bel-Is Cabulihan Nabaoy Tagororoc Mayapay Napaan Habana Habana Balusbos Jintotolo Cabugan Gibon Alegria Laserna Toledo Cantil Poblacion El Progreso Tag-Osip Nabas Nagustan Buruanga Poblacion Katipunan Buenasuerte Nazareth Alimbo-Baybay 11°50'N Buenavista Aslum 11°50'N Buenafortuna Ondoy Poblacion Colongcolong Aquino Agbago Polo San Tigum Inyawan Solido Tagbaya Isidro Matabana Tul-Ang Bugtongbato Maramig Magallanes Laguinbanua Buenavista Naisud Panilongan Pajo Santa Bagacay Cubay Luhod-Bayang Antipolo Cruz Jawili Libertad Pinatuad Capilijan Panangkilon Batuan Afga Santander San Rizal Codiong Unat Regador Paz Roque Mabusao Dumatad Poblacion Tinindugan Igcagay Candari Maloco Naligusan Bagongbayan Centro Santa Weste Baybay Lindero Barusbus Bulanao Cruz Buang Agdugayan Panayakan Tagas Union Pucio Taboc Tondog Dapdap Tinigbas San Naile Tangalan Sapatos Patria Santo Guia Joaquin Fragante Cabugao Tamalagon Baybay Duyong Rosario Zaldivar Jinalinan Santa Tingib Cabugao Pudiot Nauring Ana Lanipga Dumga Alibagon