C-Span and State Public Affairs Networks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winthrop Students Win Prizes in C-SPAN Video Documentary Competition

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: WEDNESDAY, MARCH 10, 2021 Winthrop Students Win Prizes in C-SPAN Video Documentary Competition During unprecedented times, students addressed issues of national importance WASHINGTON (March 10, 2021) – Today C-SPAN announced that students in Winthrop, Iowa, are winners in C-SPAN’s national 2021 StudentCam competition. The following students from East Buchanan Community School have won prizes: Trey Johnson, Tristan Lau and Cole Bowden will receive $250 as honorable mention winners for the documentary, "Government Subsidies for Electric Vehicles." Keira Hellenthal , Hannah McMurrin and Emma Kress will receive $250 as honorable mention winners for the documentary, "Our Future Reality," about the environment and changing climate. The competition, now in its 17th year, invited all middle and high school students to enter by producing a short documentary. C-SPAN, in cooperation with cable television partners, asked students to join the national conversation on the challenges our country is facing with the theme: "Explore the issue you most want the president and new Congress to address in 2021." Despite the unique challenges brought about by COVID-19 this year, more than 2,300 students across the country participated in the contest. C-SPAN received over 1,200 entries from 43 states and Washington, D.C. The most popular topics addressed were: Health Care (14.9%) Environmental and Energy Policy (14.6%) Equal Rights and Equity (13.5%) Criminal Justice/Policing (7.6%) Education (7.5%) "With the continual shift in the educational landscape, it is difficult to overstate just how challenging the pandemic has proven for schools across our nation," said Craig McAndrew, Director, C-SPAN Education Relations. -

The President's Desk: a Resource Guide for Teachers, Grades 4

The President’s Desk A Resource Guide for Teachers: Grades 4-12 Department of Education and Public Programs With generous support from: Edward J. Hoff and Kathleen O’Connell, Shari E. Redstone John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum Table of Contents Overview of The President’s Desk Interactive Exhibit.... 2 Lesson Plans and Activities................................................................ 40 History of the HMS Resolute Desk............................................... 4 List of Lessons and Activities available on the Library’s Website... 41 The Road to the White House...................................................................... 44 .......................... 8 The President’s Desk Website Organization The President at Work.................................................................................... 53 The President’s Desk The President’s Desk Primary Sources.................................... 10 Sail the Victura Activity Sheet....................................................................... 58 A Resource Guide for Teachers: Grades 4-12 Telephone.................................................................................................... 11 Integrating Ole Miss....................................................................................... 60 White House Diary.................................................................................. 12 The 1960 Campaign: John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Scrimshaw.................................................................................................. -

CV Available At

3/9/2017 Yale 1 Always up-to-date CV available at www.robertyale.com/cv ROBERT N. YALE Assistant Professor Satish & Yasmin Gupta College of Business [email protected] University of Dallas office: (972) 721-5058 1845 East Northgate Drive fax: (972) 721-4007 Irving, TX 75062 www.robertyale.com EDUCATION Ph.D. Purdue University | Brian Lamb School of Communication Communication Minor Areas: Quantitative Research Methods, Strategic Messaging Major Professor: Jakob D. Jensen, Communication Committee Members: Howard E. Sypher and W. Bart Collins, Communication; Jeffrey D. Karpicke, Cognitive Psychology Dissertation: Development and Validation of the Narrative Believability Scale M.A. Miami University | Department of Communication Speech Communication Thesis: Instant Messaging Communication: A Quantitative Linguistic Analysis B.A. Cedarville University | Communication Studies (with high honors) PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT 2014 Rutgers University | Rutgers Business School Mini-MBA: Social Media Marketing. Twelve-week intensive graduate program exploring ways to connect marketing and public relations objectives with social media strategies, platforms, and tactics. 2013-2014 University of Dallas | College of Business Concentration in Marketing courses. Six MBA marketing concentration courses: Foundations of Marketing, Value Based Marketing, Services Marketing, Brand Marketing, Digital Marketing Strategies, and Strategic Marketing. 2008 Purdue University | Center for Instructional Excellence Graduate Teaching Certificate. Documents involvement in classroom teaching, formal teacher development, consultative feedback, self-analysis, and teaching evaluations by supervisors and more senior faculty. AWARDS AND DISTINCTIONS 2017 Nominee, Piper Professor Award | Selected by committee as the University of Dallas nominee for the Minnie Stevens Piper Foundation Piper Professor award, given annually to ten educators in the state of Texas in recognition of their superior teaching at the college level. -

Public Service, Private Media: the Political Economy of The

PUBLIC SERVICE, PRIVATE MEDIA: THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF THE CABLE-SATELLITE PUBLIC AFFAIRS NETWORK (C-SPAN) by GLENN MICHAEL MORRIS A DISSERTATION Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2010 11 University of Oregon Graduate School Confirmation ofApproval and Acceptance of Dissertation prepared by: Glenn Morris Title: "Public Service, Private Media: The Political Economy ofthe Cable-Satellite Public Affairs Network (C-SPAN)." This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree in the Department of Journalism and Communication by: Janet Wasko, Chairperson, Journalism and Communication Carl Bybee, Member, Journalism and Communication Gabriela Martinez, Member, Journalism and Communication John Foster, Outside Member, Sociology and Richard Linton, Vice President for Research and Graduate Studies/Dean ofthe Graduate School for the University of Oregon. June 14,2010 Original approval signatures are on file with the Graduate School and the University of Oregon Libraries. 111 © 2010 Glenn Michael Morris IV An Abstract of the Dissertation of Glenn Michael Morris for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism and Communication to be taken June 2010 Title: PUBLIC SERVICE, PRIVATE MEDIA: THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF THE CABLE-SATELLITE PUBLIC AFFAIRS NETWORK (C-SPAN) Approved: _ Dr. Janet Wasko The Satellite-Cable Public Affairs Network (C-SPAN) is the only television outlet in the U.S. providing Congressional coverage. Scholars have studied the network's public affairs content and unedited "gavel-to-gavel" style of production that distinguish it from other television channels. -

C-Span Announces Winners of 2020 Studentcam Documentary Competition

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: WEDNESDAY, MARCH 11, 2020 C-SPAN ANNOUNCES WINNERS OF 2020 STUDENTCAM DOCUMENTARY COMPETITION Students explore issues of national importance in the 2020 presidential campaign Jason Lin, Amar Karoshi and Sara Yen receive $5,000 for their Grand Prize documentary, “Cmd-Delete: Technology's Damaging Effect on Democracy in 2020.” WASHINGTON (March 11, 2020) – C-SPAN announced the winners of the national 2020 StudentCam documentary competition, awarding a total of $100,000 in cash prizes to 150 winning documentaries. Each year since 2006, C-SPAN partners with local cable television providers in communities nationwide to invite middle and high school students to produce short documentaries about a subject of national importance. This year students addressed the theme, "What's Your Vision in 2020? Explore the issue you most want presidential candidates to address during the campaign." In response, nearly 5,400 students from 44 states and Washington, D.C., participated. C-SPAN received over 2,500 submissions on a variety of topics. The most popular topics addressed were: • Environment (18%) – Climate Change, Green New Deal, Pollution and Plastics • Equality/Discrimination (15%) – Prison Rights, Affirmative Action, Veterans' Rights, Human Rights • Guns (13%) – Gun Control, Mass Shootings, Second Amendment, Gun Safety • Health Care (12%) – Universal Health Care, Mental Health, Addictions, Vaping • Immigration (9%) – Border Security, Undocumented Immigration, Separation of Families, DACA "StudentCam provides a platform for young people to have their voices heard on the issues they are clearly passionate about," said C-SPAN's Director of Education Relations Craig McAndrew. "This year's entries reflect remarkable research and production values and feature a wide range of interviews with elected officials and experts. -

Spring Taps 2020

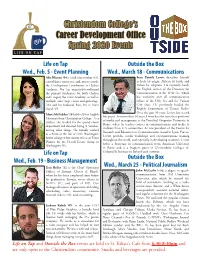

Christendom College’College’ss CarCareereer Development Office Spring 2020 Events Life on Tap Outside the Box Wed., Feb. 5 - Event Planning Wed., March 18 - Communications Alex Klassen ‘04 is a full time mother of 6, Sean Patrick Lovett describes himself retired dance instructor, and, most recently, as Irish by origin, African by birth, and the Development Coordinator at Chelsea Italian by adoption. He currently heads Academy. She has organized/coordinated the English section of the Dicastery for the primary fundraisers for both Chelsea Communication of the Holy See, which and Gregory the Great Academy, as well as has authority over all communication multiple other large events and gatherings. offices of the Holy See and the Vatican Alex and her husband, Ron, live in Front City State. He previously headed the Royal, VA. English Department of Vatican Radio. Over the past 40 years, Lovett has served Maria McFadden ‘18 holds a BA in English five popes. For more than 30 years, Lovett has also served as a professor Literature from Christendom College. As a of media and management at the Pontifical Gregorian University in student, she worked for the special events Rome, where he teaches courses in communications and media to department and directed Swing ‘n Sundaes, students from U.S. universities. As vice president of the Centre for among other things. She initially worked Research and Education in Communication, based in Lyon, France, as a florist at the Inn at Little Washington Lovett provides media workshops and communications training before taking on her current role as an Event throughout the world, and especially in developing countries. -

February-March 1998 77

GIFTED EDUCATION NEWS-PAGE VOLUME 7, NUMBER 3 Published by GIFTED EDUCATION PRESS; 10201 YUMA COURT; P.O. BOX 1586; MANASSAS, VA 20108; 703-369-5017 www.giftededpress.com BOOK NEWS AND REVIEWS BOOKNOTES: AMERICA’S FINEST AUTHORS ON READING, WRITING, AND THE POWER OF IDEAS BY BRIAN LAMB (HOST OF C-SPAN’S BOOKNOTES). TIMES BOOKS. NY. 1997. This book concentrates upon asking outstanding storytellers, reporters and public figures why and how they created their finest works. It contains over one-hundred interviews from the C-SPAN public affairs show (also called Booknotes) with individuals such as David McCullough (Truman: A Life and Times), Shelby Foote (Stars in Their Courses: The Gettysburg Campaign), Doris Kearns Goodwin (Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II), Nathaniel Branden (Judgment Day: My Years with Ayn Rand), Stephen Ambrose (D-Day, June 6, 1944: The Climatic Battle of World War II), David Halberstam (The Fifties), Elaine Sciolino (The Outlaw State: Saddam Hussein’s Quest for Power and the Gulf Crisis), Richard Nixon (Seize the Moment: America’s Challenge in a One-Superpower World), Colin Powell (My American Journey), Bill Clinton (Between Hope and History: Meeting America’s Challenges for the 21st Century), and Margaret Thatcher (The Downing Street Years). Lessons about writing, the experiences of being an author, their quirks and techniques for producing creative works, and the major influences of teachers and mentors frequently occur in these fascinating two to three page interviews. Here are some examples: Shelby Foote has written 1.5 million words about the Civil War using old-fashioned steel-point pens – “I write with a ‘dip pen,’ which causes all kinds of problems – everything from finding blotters to pen points – but it makes me take my time, and it gives me a feeling of satisfaction. -

The C-SPAN Archives: an Interdisciplinary Resource for Discovery, Learning, and Engagement

The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research Volume 1 Article 1 10-15-2014 The C-SPAN Archives: An Interdisciplinary Resource for Discovery, Learning, and Engagement Robert X. Browning Purdue University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ccse Part of the American Politics Commons Recommended Citation Browning, Robert X. (2014) "The C-SPAN Archives: An Interdisciplinary Resource for Discovery, Learning, and Engagement," The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research: Vol. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ccse/vol1/iss1/1 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. The C-SPAN Archives: An Interdisciplinary Resource for Discovery, Learning, and Engagement Cover Page Footnote To purchase a hard copy of this publication, visit: http://www.thepress.purdue.edu/titles/format/ 9781557536952 This article is available in The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ccse/vol1/iss1/1 Browning: The C-SPAN Archives: An Interdisciplinary Resource for Discovery, THE C-SPAN ARCHIVES An Interdisciplinary Resource for Discovery, Learning, and Engagement Published by Purdue e-Pubs, 2014 1 The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research, Vol. 1 [2014], Art. 1 https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ccse/vol1/iss1/1 2 Browning: The C-SPAN Archives: An Interdisciplinary Resource for Discovery, THE C-SPAN ARCHIVES An Interdisciplinary Resource for Discovery, Learning, and Engagement edited by ROBErt X. BROWNING PURDUE UNIVERSITY PRESS, WEST LAFAYETTE, INDIANA Published by Purdue e-Pubs, 2014 3 The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research, Vol. -

The Year in C-Span Archives Research Series

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Book Previews Purdue University Press 5-2018 The eY ar in C-SPAN Archives Research: Volume 4 Robert X. Browning Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_previews Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, and the Social Influence and Political Communication Commons Recommended Citation Browning, Robert X., "The eY ar in C-SPAN Archives Research: Volume 4" (2018). Purdue University Press Book Previews. 9. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_previews/9 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. THE YEAR IN ARCHIVES RESEARCH Volume 4 OTHER BOOKS IN THE YEAR IN C-SPAN ARCHIVES RESEARCH SERIES The C-SPAN Archives: An Interdisciplinary Resource for Discovery, Learning, and Engagement Exploring the C-SPAN Archives: Advancing the Research Agenda Advances in Research Using the C-SPAN Archives “Robert Browning’s annual C-SPAN research series has become a veritable scholarly institution. This year marks the 30th anniversary of the C-SPAN Video Library, and this volume’s incredible array of research projects drawn from it demonstrates its importance for our understanding of public life. In the chapters collected here, scholars analyze everything from congressional debates over mental health and law enforcement to speeches from the cam- paign trail in 2016. In doing so, the scholarship in this volume sheds light on elite rhetoric and the claims that ground policymaking and the search for public legitimacy. -

Minutes of a Regular Meeting of the Municipal Council - Township of Edison

05/25/2016 MINUTES OF A REGULAR MEETING OF THE MUNICIPAL COUNCIL - TOWNSHIP OF EDISON May 25, 2016 A Regular Meeting of the Municipal Council was held in the Council Chambers of the Municipal Building on Wednesday, May 25, 2016. The meeting was called to order at 7:02 p.m. by Council President Lombardi, followed by the Pledge of Allegiance. Present were Councilmembers Diehl, Gomez, Karabinchak, Lombardi, Patil, Sendelsky and Shah. Also present were Township Clerk Russomanno, Deputy Township Clerk McCray, Township Attorney Northgrave, Business Administrator Ruane, Township Engineer Kataryniak, Public Works Director Haines, Health Camille Spearnock , Recreation Director Halliwell, Police Deputy Chief Mieczkowski,, Battalion Chief Deak and Cameraman D’Amato. The Township Clerk advised that adequate notice of this meeting, as required by the Open Public Meetings Act of 1975, has been provided by an Annual Notice sent to The Home News Tribune, The Star Ledger, and the Sentinel on December 12, 2015 and posted in the Main Lobby of the Municipal Complex on the same date. APPROVAL OF MINUTES; On a motion made by Councilmember Gomez, seconded by Councilmember Sendelsky , and duly carried, the Minutes of the Worksession of February 22, Regular Meetings of February 24, March 9, March 23 and April 27,2016 were accepted as submitted. COUNCIL PRESIDENT’S REMARKS: Council President Lombardi invited everyone to attend our Memorial Day Parade on Sunday, May 29, 2016 at 12:00 noon starting at Division, street closing will start at 11:30am. He reminded everyone of the true meaning of Memorial Day it is the time to honor our veterans and their families who sacrificed to defend our country. -

V I E W E R ' S G U I

VIEWER’S GUIDE Created by Cable. Offered as a Public Service. THE MISSION To provide our audience with access to the live, gavel-to- • To provide the audience, through viewer call-in gavel proceedings of the U.S. House of Representatives and programs, direct access to elected officials, other the U.S. Senate and to other forums where public policy decision-makers and journalists on a frequent is discussed, debated and decided – all without editing, and open basis; commentary or analysis and with a balanced presentation of points of view; • To employ production values that accurately VIEWER’S GUIDE convey the business of government rather than • To provide elected and appointed officials and others distract from it; and who would influence public policy a direct conduit to the audience without filtering or otherwise distorting their • To conduct all other aspects of the C-SPAN points of view; networks’ operations consistent with these principles. THE C-SPAN NETWORKS The C-SPAN networks were created by the cable industry and With headquarters in Washington, D.C., C-SPAN employs are offered as a public service to provide access to balanced, more than 250 people who work to fulfill cable’s Covering the Events that Shape the Nation commercial-free coverage of the American political process. commitment to public affairs programming. The networks The networks are privately funded by the cable industry and also provide other information and education services, without government or taxpayer support. including C-SPAN.org, C-SPAN Radio, C-SPAN Classroom and the C-SPAN Bus. VIEWER’S GUIDE C-SPAN was launched in 1979 to provide live, gavel-to-gavel coverage of the U.S. -

C-SPAN, the Cable TV Channel

C-SPAN, the Cable TV channel C-SPAN, the Cable-Satellite Public Affairs Network is a medium that truly brings the government to the people. By presenting live and uncut footage of our government in action, the citizens of the United States can get a bit closer to what the founding fathers had in mind when they created our government. C-SPAN is truly a unique channel amongst the mass of today's viewing options. C-SPAN was launched March 19, 1979, "to provide live, gavel to gavel coverage of the United States House of Representatives."1, but the enterprise has been expanded beyond the original one channel and now utilizes several mediums to reach its goal. The originator of this idea of bringing government into peoples' homes was Brian Lamb, who in addition to being the chairman and CEO of C-SPAN, is also a host on many of C-SPAN's programs. Brian's primary belief is that people should be able to see government in action without soundbites, computer maps, models, images, music, and news anchor commentary. Brian feels that if people can see government in action without the normal clutter, then they can more easily make decisions for themselves about politics and the workings of their government. In addition to C-SPAN, a second channel, C-SPAN2 has also been created. C-SPAN2 is committed to providing live and uncut coverage of the U.S. Senate when it is in session. C-SPAN2 continues the tradition of the original channel by giving an even wider unfiltered and unplugged view of our government in action.