Pilkadaris Terry and Others V Asian Tour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 2014 Vol.7 Issue No.2

www.indiangolfunion.org THE OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE INDIAN GOLF UNION Second Quarter - August 2014 Vol.7 Issue No.2 In this issue President’s Message President’s Message 1 Director General’s Message 2 Greetings and here’s wishing you a happy Independence Editorial 2 Day and a great year ahead. Amateur Golf in India has Features progressed rapidly in the past few years and Junior golf - Playing in the “Zone”... 3 has been growing so fast that the IGU was pleased to start Committee Reports the zonal feeder tours to accommodate the expanding - Ladies Committee 4 numbers. Skill levels on the national tours keep on Features improving such that the foremost players are turning - Shaili Speaks 4 professional while still in their teens! We are also seeing a Rules & Regulations dichotomy or sorts. On one hand we are always on our - Hornets and More 5 toes to nurture the next level of players, which ultimately Features increases depth in our ranks. On the other, medals may - At the 2014 Open Championships 6 - At the Land of the Royal Liverpudlians 7 not be won at every outing, as youngsters on the team have to go through the process of - A “Pinefull” Experience 8 getting competition exposure on the big stage. - Amateur Golf Championships 10 This is a call to all amateurs to hone your skills and play abroad at the best of courses Merit List 11 against top competition–all at the cost of the IGU! THE IGU COUNCIL Golf, when compared to other sports, provides an extended window for competitive President - Raian F Irani play. -

Larry Petryk – PGA Golf Professional

Larry Petryk – PGA Golf Professional Personal Born and raised in the small town of Smoky Lake, Alberta. History Began playing golf at the age of 13. Smoky Lake Golf Club: Board of directors at the age of 16. Helped develop the golf course and it's transition from sand to grass greens. Winner of numerous club championships. Graduated High School: H. A. Kostash (Smoky Lake) Professional Memberships 2014 - Present PGA of Canada Member 2006 – 2014 Member of The Macau Professional Golfer’s Association 2007 - 2011 Chief Operating Officer MPGA: Organized and hosted events such as Pro-Ams, Corporate Golf Clinics and Seminars, Junior Golf Events, and General MPGA Assembly meetings. Professional 16+ Years of Instructing & Coaching: Teaching Taught golf in Canada, the US, and overseas in China to juniors, ladies, & men (beginners, intermediate amateurs, elite amateurs, & professionals). Experience Conducted group lessons, clinics, & seminars on subjects such as increasing power, short game, stop-slicing, etc. 2016 - Present Head Teaching Golf Professional at Raven Crest Golf Club (Larry Petryk Golf Academy) 2014 – 2015 Head Teaching Golf Professional at EGMGCC (& Pro Shop Supervisor) 2009 – 2012 Head Teaching Golf Professional at the Macau Golf and Country Club 2007 – 2008 Teaching Golf Professional at the Orient Macau Golf Club, Macau, China 2006 - 2007 The International School of Macau – Golf in physical education 2004, 2005, Concordia University College Golf Coach, Edmonton, Canada. 2013, 2018 2018 Provincial ACAC Championships: Men's Team -2nd Women's Team 3rd. 2003 – 2004 Touring & Assistant Teaching Professional, Billy’s D’s Golf Center, Edmonton, Canada. Co-taught group classes to Jr. -

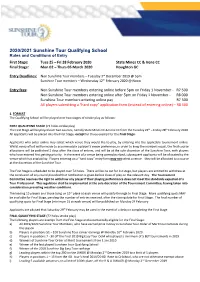

2020/2021 Sunshine Tour Qualifying School Rules and Conditions of Entry

2020/2021 Sunshine Tour Qualifying School Rules and Conditions of Entry First Stage: Tues 25 – Fri 28 February 2020 State Mines CC & Irene CC Final Stage: Mon 02 – Thurs 05 March 2020 Houghton GC Entry Deadlines: Non Sunshine Tour members – Tuesday 3rd December 2019 @ 5pm Sunshine Tour members – Wednesday 12th February 2020 @ Noon Entry fees: Non Sunshine Tour members entering online before 5pm on Friday 1 November - R7 500 Non Sunshine Tour members entering online after 5pm on Friday 1 November - R8 000 Sunshine Tour members entering online pay R7 500 All players submitting a “hard copy” application form (instead of entering online) – R8 500 1. FORMAT The Qualifying School will be played over two stages of stroke play as follows: FIRST QUALIFYING STAGE (72 holes stroke play) The First Stage will be played over two courses, namely State Mines CC & Irene CC from the Tuesday 25th – Friday 28th February 2020. All applicants will be placed into the First Stage, except for those exempt for the Final Stage. Applicants who enter online may select which venue they would like to play, by entering into the applicable tournament online. Whilst every effort will be made to accommodate a player’s venue preference, in order to keep the numbers equal, the final course allocations will be published 2 days after the close of entries, and will be at the sole discretion of the Sunshine Tour, with players who have entered first getting priority. In the event of a venue being oversubscribed, subsequent applicants will be allocated to the venue which has availability. -

Annual Review 2018 Scottish Golf Annual Review 2018 Scottish Golf Annual Review

2018 Scottish Golf Annual Review 2018 SCOTTISH GOLF ANNUAL REVIEW 2018 SCOTTISH GOLF ANNUAL REVIEW with more than 60% of the membership voting in favour of a more modest increase to the Per Capita Fee, enabled Scottish Golf to commit to a series of measures designed to reinvigorate the game. A new platform is already being tested that will not only connect the game in an unprecedented manner in Scotland, providing new marketing and sales opportunities for clubs, but also provide the flexibility to introduce the many thousands of pay-per-play golfers whose integration into the golfing family has been long overdue. We have provided a commitment to ring-fence funds for the development of the game among our clubs as part of an overarching strategy to increase participation, especially among women and young people, to support club development “ at all levels, and to increase commercial revenue. A goal without The platform is the central pillar of this strategy and the key to a plan is just delivering an enhanced service for all golfers now and in the future. a wish. ” The current membership is the lifeblood of our game and we are grateful to all who have shared their views on a range of Welcome important subjects. That passion is the heart of golf and I am CEO Introduction certain we are already on a stronger footing. A goal without a plan is just a wish. I am pleased to report that It is not only an important leap into the digital world but, as from the Chair This year promises to be a hugely exciting one. -

Smbc Singapore Open Wins Top Award It Is the Best Tournament for 2017, While Sentosa’S Serapong Claims Best Course Honours

BY GODFREY ROBERT SMBC SINGAPORE OPEN WINS TOP AWARD IT IS THE BEST TOURNAMENT FOR 2017, WHILE SENTOSA’S SERAPONG CLAIMS BEST COURSE HONOURS he SMBC Singapore Open beat 27 other Asian Tour events to be voted the Best Tournament of the Year 2017. The Singapore event came out tops in a voting exercise by more than 300 golfers who play in Asia, Europe, Africa and Australia. Although the prize-money for the event had dropped from a high of US$7 million to US$1 million, the Singapore Open, Tinaugurated in 1961, is a very popular tournament even among the world’s best players. Previous winners of the award include Ho Tram Cham- pionship in Vietnam and the Thailand Golf Championship in Thailand. Golfers such as Jordan Spieth, Phil Mickelson, Adam Scott, Angel Cabrera and Sergio Garcia have graced the Sin- gapore Open which has made Sentosa Golf Club’s world- acclaimed Serapong course its home since 2005. So it came as no surprise that at the Asian Tour’s annu- al awards gala night at the Royal Jakarta Golf Club on Dec 17, the Serapong layout was named the Best Course of the Year for 2017. Promoters Lagardere Sports’ vice president (Golf Asia) Patrick Feizal Joyce said: “Winning the tournament of the year on the Asian Tour is a terrific accolade and one we are extremely proud of. The acknowledgement from the DISCOVER GOLF CARNIVAL: Patrick Feizal Joyce, Vice President, players that our event is the one that sets the bar and an The Discover Golf Carnival on Jan 14 (from 2pm to 6pm) Golf — Asia, Lagardère Sports, receives the award from Cho Minn event they truly look forward to is tremendous validation at Sentosa Golf Club will feature various fun activities Thant (above, right), COO, Asian Tour. -

Anne, Le Musical Viel Chante Brel Et Du West-End Frères Jacques

ÉDITO MUSICALS MAGAZINE est édité par Matthieu Gallou Entertainment 14, rue Cavé, 75018 Paris N°9 - PRinTemPS 2009 EN ATTendanT L'ÉTÉ... Tirage : 1 000 exemplaires Directeur de la publication : À l’heure où nous imprimons ce numéro, nous ne pouvons pas encore vous annoncer la pro- Matthieu Gallou grammation officielle du festival Les Musicals qui se tiendra à Paris du 6 au 26 juillet 2009. Ce Rédacteur en chef : Matthieu Gallou Rédactrice en chef adjointe : sera chose faite début avril sur le site www.lesmusicals.com. Par contre, nous connaissons l’am- Geneviève Krieff pleur de la programmation : entre 25 et 30 musicals, tous genres confondus (tout public, jeune Rédacteurs : Vanessa Bertran - Gilles de Lesdain public, comédies musicales, spectacles musicaux, opérettes) et plus de 200 représentations ! Gabriel Elian - Dorothée Gallou Les organisateurs ont aussi déterminé un tarif unique pour tous les spectacles : 19€. Ce qui Benjamin Giraud - Anne-Marie Hallynck Nicolas Maille - Hélène Milon permet d’accéder à des spectacles de premier ordre et normalement affichés à 30, 35 € la place. Michel Pouradier - Sébastien Riché Ceux qui ne partent pas en vacances, ceux qui travaillent encore, mais aussi les jeunes et les Christine Sabban - Tomoko Sawauchi Nicolas Williamson séniors pourront ainsi s’offrir des sorties à portée de leurs moyens. Secrétaire de redaction : Josée Krieff - Anne-Marie Hallynck La fin de saison approche et les récompenses commencent à être distribuées. Hélène Milon Conception graphique Après les Césars, les Oscars, les Tony Awards, les Victoires de la Musique et et mise en page : Geneviève Krieff les Molières, se profile la cérémonie des Marius, honorant les (www.genevievekrieff.com) meilleurs musicals de l’année et les meilleurs interprètes. -

BMW SA OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP Proudly Hosted by City of Ekurhuleni

ENTRY FORM BMW SA OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP Proudly Hosted by City of Ekurhuleni To be played at Glendower Golf Club From 12th – 15th January 2017 ENTRY FEE R250* * The entry fee for European Tour members is determined by their Tour's Members' General Regulations Handbook. CLOSE OF ENTRIES: Non Sunshine Tour or European Tour Members: 5PM (SA TIME) ON MONDAY 12TH DECEMBER 2016 2016/2017 Sunshine Tour & 2017 European Tour Members: 5PM (SA TIME) ON MONDAY 19TH DECEMBER 2016 Address: Southern Africa PGA Tour, PostNet Suite # 185, Private Bag X15, Somerset West, 7129, South Africa BMW SA OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP Proudly Hosted by City of Ekurhuleni To enter, please complete the form below and return, with the proof of payment of the entrance fee to [email protected] or fax # +27 (0) 21 852 8271 Surname: ______________________________ First Name (Known As name): ______________________________ Nationality: ______________________________ Date of Birth: __________________________________________ Postal Address: _________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ Post Code ___________________ Home Tel: (_____) _____________________________Mobile: (_____) _____________________________________ E-mail Address: _________________________________________________________________________________ If exempt from qualifying, please quote authority here: ____________________________________________________ I have read the Information and Conditions and agree to abide thereby: -

Singapore Open to Return in 2016 Tournament Reborn with Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (SMBC) As a New Title Sponsor

Singapore Open To Return In 2016 Tournament Reborn with Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (SMBC) as a New Title Sponsor Singapore, 28 January 2015 – After a three-year absence, Singapore’s iconic national Open will make a welcome return with a new title sponsor and sanctioning partner. Last staged in 2012, the SMBC Singapore Open is set to thrill local golf fans and global audiences alike when it roars back to life from January 28 to 31, 2016 at the scene of past dramatic editions, the Serapong Course at Sentosa Golf Club. Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (SMBC), one of Japan’s leading financial institutions and a growing presence in the banking sector in Asia and worldwide, has taken on the mantle as title sponsor with this landmark three-year association with golf in Singapore. “We are honoured to be the title sponsor and support the tournament as the SMBC Singapore Open,” said Mr. Masayuki Shimura, Managing Director and Head of Asia Pacific Division, SMBC. “The Singapore Open has great history, great champions, and is recognized globally as one of the premier golf tournaments. We look forward to adding to that legacy and further expanding our corporate brand in Asia with our growing focus to the region, as well as contributing to the expansion of golf in Asia through the development of the next generation golfers in Asia.” Asian Tour Chairman Kyi Hla Han was effusive. “The Singapore Open was always one of our best events and one that our members strove to compete well in. It is tremendous to have it back as it is an important event for our region and our tour. -

PLAYERS GUIDE — Shinnecock Hills Golf Club | Southampton, N.Y

. OP U.S EN SHINNECOCK HILLS TH 118TH U.S. OPEN PLAYERS GUIDE — Shinnecock Hills Golf Club | Southampton, N.Y. — June 14-17, 2018 conducted by the 2018 U.S. OPEN PLAYERS' GUIDE — 1 Exemption List SHOTA AKIYOSHI Here are the golfers who are currently exempt from qualifying for the 118th U.S. Open Championship, with their exemption categories Shota Akiyoshi is 183 in this week’s Official World Golf Ranking listed. Birth Date: July 22, 1990 Player Exemption Category Player Exemption Category Birthplace: Kumamoto, Japan Kiradech Aphibarnrat 13 Marc Leishman 12, 13 Age: 27 Ht.: 5’7 Wt.: 190 Daniel Berger 12, 13 Alexander Levy 13 Home: Kumamoto, Japan Rafael Cabrera Bello 13 Hao Tong Li 13 Patrick Cantlay 12, 13 Luke List 13 Turned Professional: 2009 Paul Casey 12, 13 Hideki Matsuyama 11, 12, 13 Japan Tour Victories: 1 -2018 Gateway to The Open Mizuno Kevin Chappell 12, 13 Graeme McDowell 1 Open. Jason Day 7, 8, 12, 13 Rory McIlroy 1, 6, 7, 13 Bryson DeChambeau 13 Phil Mickelson 6, 13 Player Notes: ELIGIBILITY: He shot 134 at Japan Memorial Golf Jason Dufner 7, 12, 13 Francesco Molinari 9, 13 Harry Ellis (a) 3 Trey Mullinax 11 Club in Hyogo Prefecture, Japan, to earn one of three spots. Ernie Els 15 Alex Noren 13 Shota Akiyoshi started playing golf at the age of 10 years old. Tony Finau 12, 13 Louis Oosthuizen 13 Turned professional in January, 2009. Ross Fisher 13 Matt Parziale (a) 2 Matthew Fitzpatrick 13 Pat Perez 12, 13 Just secured his first Japan Golf Tour win with a one-shot victory Tommy Fleetwood 11, 13 Kenny Perry 10 at the 2018 Gateway to The Open Mizuno Open. -

Slice Proof Swing Tony Finau Take the Flagstick Out! Hot List Golf Balls

VOLUME 4 | ISSUE 1 MAY 2019 `150 THINK YOUNG | PLAY HARD PUBLISHED BY SLICE PROOF SWING TONY FINAU TAKE THE FLAGSTICK OUT! HOT LIST GOLF BALLS TIGER’S SPECIAL HERO TRIUMPH INDIAN GREATEST COMEBACK STORY OPEN Exclusive Official Media Partner RNI NO. HARENG/2016/66983 NO. RNI Cover.indd 1 4/23/2019 2:17:43 PM Roush AD.indd 5 4/23/2019 4:43:16 PM Mercedes DS.indd All Pages 4/23/2019 4:45:21 PM Mercedes DS.indd All Pages 4/23/2019 4:45:21 PM how to play. what to play. where to play. Contents 05/19 l ArgentinA l AustrAliA l Chile l ChinA l CzeCh republiC l FinlAnd l FrAnCe l hong Kong l IndIa l indonesiA l irelAnd l KoreA l MAlAysiA l MexiCo l Middle eAst l portugAl l russiA l south AFriCA l spAin l sweden l tAiwAn l thAilAnd l usA 30 46 India Digest Newsmakers 70 18 Ajeetesh Sandhu second in Bangladesh 20 Strong Show By Indians At Qatar Senior Open 50 Chinese Golf On The Rise And Yes Don’t Forget The 22 Celebration of Women’s Golf Day on June 4 Coconuts 54 Els names Choi, 24 Indian Juniors Bring Immelman, Weir as Laurels in Thailand captain’s assistants for 2019 Presidents Cup 26 Club Round-Up Updates from courses across India Features 28 Business Of Golf Industry Updates 56 Spieth’s Nip-Spinner How to get up and down the spicy way. 30 Tournament Report 82 Take the Flagstick Out! Hero Indian Open 2019 by jordan spieth Play Your Best We tested it: Here’s why putting with the pin in 60 Leadbetter’s Laser Irons 75 One Golfer, Three Drives hurts more than it helps. -

2019 All Thailand Golf Tour Annual Qualifying School

All Thailand Golf Tour 7/F, Supreme Complex, 1024 Samsen Road, Dusit, Bangkok 10300, Thailand Tel: + (662) 667-4250 Fax: + (662) 667-4252 2019 ALL THAILAND GOLF TOUR ANNUAL QUALIFYING SCHOOL I. INTRODUCTION Beginning in the 2019 season and onwards, the All Thailand Golf Tour (“ATGT”) shall hold an annual qualifying school (“Q-School”). The leading 35 applicants and ties at the Final Qualifying Stage shall be entitled to Member Exemption Category 15 and shall join the leaders on the previous year’s Order of Merit and certain other exempt players as ATGT members in the 2019 season. The list of Member Exemption Categories is noted in Appendix 1. The ATGT expects a very competitive Q-School that will be run in the following two stages: Venue: Watermill Golf Club & Resort Address: 44 Moo 2 Photan, Ongkaruk, Nakornnayok 26120 Tel: (662) 549-1555-8, (666) 4936-0029 (A) First Qualifying Stage: Date: 4 – 7 December 2018 Any applicant who did not meet the eligibility criteria for the Final Qualifying Stage has to compete in the First Qualifying Stage that is played over four rounds. (B) Final Qualifying Stage: Date: 11 – 14 December 2018 Applicants who meet the eligibility criteria for the Final Qualifying Stage and applicants who qualify from the First Qualifying Stage shall compete in the Final Qualifying Stage that is played over four rounds. Closing Date for Applications: 31 October 2018 (5:00 PM, Thailand time) II. QUALIFYING SCHOOL FORMAT The Q-School will be conducted in two stages. (A) First Qualifying Stage: Dates: 4 - 7 December 2018 Practice Round: 3 December 2018 Player Registration: 2 December 2018; 7:00 AM – 4:00 PM (Thailand time) 3 December 2018; 7:00 AM – 12:00 PM (Thailand time) Applicants shall be allocated spots on a “first come, first serve” basis and subject to availability. -

Online Newshour and Newshour Extra Release

Using NewsHour Extra Feature Stories STORY What Does Lady Gaga’s Asia Tour Say About the Global Economy? 05/14/2012 http://www.pbs.org/newshour/extra/features/arts/jan-june12/gaga_05-14.html Estimated Time: One 45-minute class period with possible extension Student Worksheet (reading comprehension and discussion questions without answers) PROCEDURE 1. WARM UP Use initiating questions to introduce the topic and find out how much your students know. 2. MAIN ACTIVITY Have students read NewsHour Extra's feature story and answer the reading comprehension and discussion questions on the student handout. 3. DISCUSSION Use discussion questions to encourage students to think about how the issues outlined in the story affect their lives and express and debate different opinions.] INITIATING QUESTIONS 1. Why do musicians go on tour? 2. What do you know about Asia and its culture? 3. How do musicians like Lady Gaga make money? READING COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS – Student Worksheet 1. Where did Lady Gaga kick off her tour for the album “Born This Way?” Seoul, South Korea 2. Where else will the tour stop? Hong Kong, Taiwan’s Taipei, Jakarta in Indonesia, Singapore, and Bangkok in Thailand 3. What Asian country has always been a destination for successful music artists? Japan 4. Who is encouraging people to boycott Lady Gaga’s concerts? Religious groups from Christians in Korea to Muslims in Indonesia 5. How many tickets to Lady Gaga’s show were sold in the first two hours in Jakarta? 25,000 6. What is the new minimum age for people to attend Lady Gaga’s concerts in South Korea? 18 years old http://www.pbs.org/newshour/extra/ 1 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS (more research might be needed) 1.