Michael Erlewine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014–2015 Season Sponsors

2014–2015 SEASON SPONSORS The City of Cerritos gratefully thanks our 2014–2015 Season Sponsors for their generous support of the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts. YOUR FAVORITE ENTERTAINERS, YOUR FAVORITE THEATER If your company would like to become a Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts sponsor, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at 562-916-8510. THE CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (CCPA) thanks the following current CCPA Associates donors who have contributed to the CCPA’s Endowment Fund. The Endowment Fund was established in 1994 under the visionary leadership of the Cerritos City Council to ensure that the CCPA would remain a welcoming, accessible, and affordable venue where patrons can experience the joy of entertainment and cultural enrichment. For more information about the Endowment Fund or to make a contribution, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. MARQUEE Sandra and Bruce Dickinson Diana and Rick Needham Eleanor and David St. Clair Mr. and Mrs. Curtis R. Eakin A.J. Neiman Judy and Robert Fisher Wendy and Mike Nelson Sharon Kei Frank Jill and Michael Nishida ENCORE Eugenie Gargiulo Margene and Chuck Norton The Gettys Family Gayle Garrity In Memory of Michael Garrity Ann and Clarence Ohara Art Segal In Memory Of Marilynn Segal Franz Gerich Bonnie Jo Panagos Triangle Distributing Company Margarita and Robert Gomez Minna and Frank Patterson Yamaha Corporation of America Raejean C. Goodrich Carl B. Pearlston Beryl and Graham Gosling Marilyn and Jim Peters HEADLINER Timothy Gower Gwen and Gerry Pruitt Nancy and Nick Baker Alvena and Richard Graham Mr. -

Jukebox Oldies

JUKEBOX OLDIES – MOTOWN ANTHEMS Disc One - Title Artist Disc Two - Title Artist 01 Baby Love The Supremes 01 I Heard It Through the Grapevine Marvin Gaye 02 Dancing In The Street Martha Reeves & The Vandellas 02 Jimmy Mack Martha Reeves & The Vandellas 03 Reach Out, I’ll Be There Four Tops 03 You Keep Me Hangin’ On The Supremes 04 Uptight (Everything’s Alright) Stevie Wonder 04 The Onion Song Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell 05 Do You Love Me The Contours 05 Got To Be There Michael Jackson 06 Please Mr Postman The Marvelettes 06 What Becomes Of The Jimmy Ruffin 07 You Really Got A Hold On Me The Miracles 07 Reach Out And Touch Diana Ross 08 My Girl The Temptations 08 You’re All I Need To Get By Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell 09 Where Did Our Love Go The Supremes 09 Reflections Diana Ross & The Supremes 10 I Can’t Help Myself Four Tops 10 My Cherie Amour Stevie Wonder 11 The Tracks Of My Tears Smokey Robinson & The Miracles 11 There’s A Ghost In My House R. Dean Taylor 12 My Guy Mary Wells 12 Too Busy Thinking About My Marvin Gaye 13 (Love Is Like A) Heatwave Martha Reeves & The Vandellas 13 The Happening The Supremes 14 Needle In A Haystack The Velvelettes 14 It’s A Shame The Spinners 15 It’s The Same Old Song Four Tops 15 Ain’t No Mountain High Enough Diana Ross 16 Get Ready The Temptations 16 Ben Michael Jackson 17 Stop! (in the name of love) The Supremes 17 Someday We’ll Be Together Diana Ross & The Supremes 18 How Sweet It Is Marvin Gaye 18 Ain’t Too Proud To Beg The Temptations 19 Take Me In Your Arms Kim Weston 19 I’m Still Waiting Diana Ross 20 Nowhere To Run Martha Reeves & The Vandellas 20 I’ll Be There The Jackson 5 21 Shotgun Junior Walker & The All Stars 21 What’s Going On Marvin Gaye 22 It Takes Two Marvin Gaye & Kim Weston 22 For Once In My Life Stevie Wonder 23 This Old Heart Of Mine The Isley Brothers 23 Stoned Love The Supremes 24 You Can’t Hurry Love The Supremes 24 ABC The Jackson 5 25 (I’m a) Road Runner JR. -

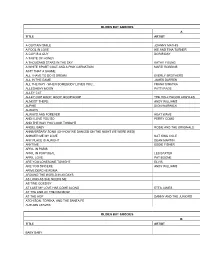

Oldies but Goodies a Title Artist a Certain Smile Johnny Mathis a Fool in Love Ike and Tina Turner a Guy Is a Guy Doris Day a Ta

OLDIES BUT GOODIES A TITLE ARTIST A CERTAIN SMILE JOHNNY MATHIS A FOOL IN LOVE IKE AND TINA TURNER A GUY IS A GUY DORIS DAY A TASTE OF HONEY A THOUSAND STARS IN THE SKY KATHY YOUNG A WHITE SPORT COAT AND A PINK CARNATION MARTI ROBBINS AIN'T THAT A SHAME ALL I HAVE TO DO IS DREAM EVERLY BROTHERS ALL IN THE GAME JAMES DARREN ALL THE WAY - WHEN SOMEBODY LOVES YOU… FRANK SINATRA ALLEGHENY MOON PATTI PAGE ALLEY CAT ALLEY OOP BOOP, BOOP, BOOP BOOP THE HOLLYWOOD ARGYLES ALMOST THERE ANDY WILLIAMS ALPHIE DION WARWICK ALWAYS ALWAYS AND FOREVER HEAT WAVE AND I LOVE YOU SO PERRY COMO AND THE WAY YOU LOOK TONIGHT ANGEL BABY ROSIE AND THE ORIGINALS ANNIVERSARY SONG (OH HOW WE DANCED ON THE NIGHT WE WERE WED) ANSWER ME MY LOVE NAT KING COLE ANY PLACE IS ALRIGHT DEAN MARTIN ANYTIME EDDIE FISHER APRIL IN PARIS APRIL IN PORTUGAL LES BAXTER APRIL LOVE PAT BOONE ARE YOU LONESOME TONIGHT ELVIS ARE YOU SINCERE ANDY WILLIAMS ARIVE DERCHE ROMA AROUND THE WORLD IN 80 DAYS AS LONG AS SHE NEEDS ME AS TIME GOES BY AT LAST MY LOVE HAS COME ALONG ETTA JAMES AT THE END OF THE RAINBOW AT THE HOP DANNY AND THE JUNIORS ATCHISON, TOPEKA, AND THE SANTA FE AUTUMN LEAVES OLDIES BUT GOODIES B TITLE ARTIST BABY BABY BABY DON'T SAY DON'T ELVIS PRESLEY BABY ELEPHANT WALK BABY I'M YOURS MAMA CASS BAND OF GOLD BARBARA ANN THE BEACH BOYS BECAUSE (YOU'VE COME TO ME) PERRY COMO BECAUSE OF YOU BEWITCHED, BOTHERED AND BEWILDERED BIG JOHN JIMMY DEAN BIG MAN FOUR PREPS BIRD DOG EVERLY BROTHERS BLAME IT ON THE BOSANOVA BLOWIN' IN THE WIND PETER PAUL & MARY BLUE HAWAII ELVIS PRESLEY BLUE -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

The Arizona Record Label Discography

1 The Arizona Record Label Discography By John P. Dixon RAMCO 3701 3702 Bob Cox I Live Alone / Don't Hold Her So Close ‘60 3703 Jim Murphey The Jenny Lee / Nobody's Darlin' But Mine ‘60 3704 Jerry Davis I Sold My Heart to the JunkMan / So Broke up ’61 3705 Al Casey Combo A Cookin’ / Hot Foot ‘61 3706 The Darnell Brothers It's Me / Little Two Face ‘61 3707 Ritchie Hart Vacation TiMe / Her Singing Idol ‘61 3708 Jack Cook Run Boy Run / I Gotta Book ‘61 3709 Ritchie Hart & Heartbeats Do It Twist / Phyllis ‘61 3710 Little Worley and the Drops Who Stole My Girl / You Better Watch Yourself ‘61 3711 Terry Wells Her Song / Terry’s TheMe ‘62 3712 The Prophets Ape / Japanese Twist ‘62 3713 Arv Jenkins Jenny Gaylor / Runnin' Wild (Picture Sleeve) ‘62 3714 Frankie and the Favorites Whirlaway / Phyllis ‘62 3715 The Vice-Roys My Heart / I Need Your Love So Bad Jim Musil ‘62 3716 Ritchie Hart So Far Away From Home / Love ls ‘62 3717 The Versatiles w/ M.M. CoMbo Blue Feelin’ / Just Pretending Jim Musil ‘63 3718 JimMy Grey My World / Late Last Night ‘63 3719 Jody Brian Quartet Drifting HoMe To You / Cabin on the Hill ‘63 3720 Jane Darwin His and Hers / Half A WoMan Jerry Davis/Joe English ‘63 3721 Jack Cook B Walk Another Mile / My Evil Mind ‘63 3722 Johnny Lance C* All About Julie * / Mountain In The Rainbow Jody Reynolds/Floyd RaMsey ‘63 3723 Donny Owens DreaM Girl / My Love ‘63 3724 Larry Rickard & Heart Beats Doctor Love / Lived My Life In Pain ‘63 3725 Brother Zee & Decades Smokey the Bear / Sha-BooM Bang Jim Musil ‘63 3726 Pee Wee Sutton You Don’t Thrill Me / That’s What I DreaMed Last Night ‘64 3727 Don Rutherford D E The PunishMent of Love/Skadawdawreetawrawskrawnskrillyawnskraw(The EskiMo Song) ‘64 3728 Mack Fields I Like To Yodel / O, How The TiMe Does Fly ‘64 3729 Mary Keel ChristMas Is A Season / Dear Mr. -

Thanks to John Frank of Oakland, California for Transcribing and Compiling These 1960S WAKY Surveys!

Thanks to John Frank of Oakland, California for transcribing and compiling these 1960s WAKY Surveys! WAKY TOP FORTY JANUARY 30, 1960 1. Teen Angel – Mark Dinning 2. Way Down Yonder In New Orleans – Freddy Cannon 3. Tracy’s Theme – Spencer Ross 4. Running Bear – Johnny Preston 5. Handy Man – Jimmy Jones 6. You’ve Got What It Takes – Marv Johnson 7. Lonely Blue Boy – Steve Lawrence 8. Theme From A Summer Place – Percy Faith 9. What Did I Do Wrong – Fireflies 10. Go Jimmy Go – Jimmy Clanton 11. Rockin’ Little Angel – Ray Smith 12. El Paso – Marty Robbins 13. Down By The Station – Four Preps 14. First Name Initial – Annette 15. Pretty Blue Eyes – Steve Lawrence 16. If I Had A Girl – Rod Lauren 17. Let It Be Me – Everly Brothers 18. Why – Frankie Avalon 19. Since You Broke My Heart – Everly Brothers 20. Where Or When – Dion & The Belmonts 21. Run Red Run – Coasters 22. Let Them Talk – Little Willie John 23. The Big Hurt – Miss Toni Fisher 24. Beyond The Sea – Bobby Darin 25. Baby You’ve Got What It Takes – Dinah Washington & Brook Benton 26. Forever – Little Dippers 27. Among My Souvenirs – Connie Francis 28. Shake A Hand – Lavern Baker 29. It’s Time To Cry – Paul Anka 30. Woo Hoo – Rock-A-Teens 31. Sand Storm – Johnny & The Hurricanes 32. Just Come Home – Hugo & Luigi 33. Red Wing – Clint Miller 34. Time And The River – Nat King Cole 35. Boogie Woogie Rock – [?] 36. Shimmy Shimmy Ko-Ko Bop – Little Anthony & The Imperials 37. How Will It End – Barry Darvell 38. -

Songs by Artist

Nice N Easy Karaoke Songs by Artist Bookings - Arie 0401 097 959 10 Years 50 Cent A1 Through The Iris 21 Questions Everytime 10Cc Candy Shop Like A Rose Im Not In Love In Da Club Make It Good Things We Do For Love In Da' Club No More 112 Just A Lil Bit Nothing Dance With Me Pimp Remix Ready Or Not Peaches Cream Window Shopper Same Old Brand New You 12 Stones 50 Cent & Olivia Take On Me Far Away Best Friend A3 1927 50 Cents Woke Up This Morning Compulsory Hero Just A Lil Bit Aaliyah Compulsory Hero 2 50 Cents Ft Eminem & Adam Levine Come Over If I Could My Life (Clean) I Don't Wanna 2 Pac 50 Cents Ft Snoop Dogg & Young Miss You California Love Major Distribution (Clean) More Than A Woman Dear Mama 5Th Dimension Rock The Boat Until The End Of Time One Less Bell To Answer Aaliyah & Timbaland 2 Unlimited 5Th Dimension The We Need A Resolution No Limit Aquarius Let The Sun Shine In Aaliyah Feat Timbaland 20 Fingers Stoned Soul Picnic We Need A Resolution Short Dick Man Up Up And Away Aaron Carter 3 Doors Down Wedding Bell Blues Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Away From The Sun 702 Bounce Be Like That I Still Love You How I Beat Shaq Here Without You 98 Degrees I Want Candy Kryptonite Hardest Thing The Aaron Carter & Nick Landing In London I Do Cherish You Not Too Young, Not Too Old Road Im On The Way You Want Me To Aaron Carter & No Secrets When Im Gone A B C Oh, Aaron 3 Of Hearts Look Of Love Aaron Lewis & Fred Durst Arizona Rain A Brooks & Dunn Outside Love Is Enough Proud Of The House We Built Aaron Lines 3 Oh 3 A Girl Called Jane Love Changes -

Music-Industry-Vs-Pandora.Pdf

INDEX NO. UNASSIGNED NYSCEF DOC. NO. 1 RECEIVED NYSCEF: 04/17/2014 SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF NEW YORK CAPITOL RECORDS, LLC, a Delaware INDEX NO. limited liability corporation; SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT, a Delaware partnership; UMG RECORDINGS, INC., a Delaware corporation; WARNER MUSIC GROUP CORP., a Delaware corporation, and ABKCO MUSIC & RECORDS, INC., a New York corporation, Plaintiffs, V. SUMMONS PANDORA MEDIA, INC., a Delaware Corporation; and DOES 1 through 10, being fictitious and unknown to Plaintiffs, being participants in all or some of the acts alleged against the Defendants in the Complaint, Defendants. To the above named Defendant(s) You are hereby summoned to answer the complaint in this action and to serve a copy of your answer, or, if the complaint is not served with this summons, to serve a notice of appearance, on the Plaintiffs attorney within 20 days after the service of this summons, exclusive of the day of service (or within 30 days after the service is complete if this summons is not personally delivered to you within the State of New York); and in case of your failure to appear or answer, judgment will be taken against you by default for the relief demanded in the complaint. Plaintiff has designated venue as New York County, pursuant to CPLR § 503. The basis for venue in New York County is made pursuant to CPLR § 503(a) and (c). 6032919.1/11224-00128 DATED: New York, New York MITCHELL SILBERBERG & KNUPP LLP April 17, 2014 By: auren J. Wachtler 12 East 49th Street', 30th Floor New York, New York 10017-1028 Telephone: (212) 509-3900 Facsimile: (212) 509-7239 Russell J. -

The Arizona Record Label Discography

1 The Arizona Record Label Discography By John P. Dixon RAMCO 3701 3702 Bob Cox I Live Alone / Don't Hold Her So Close ‘60 3703 Jim Murphey The Jenny Lee / Nobody's Darlin' But Mine ‘60 3704 Jerry Davis I Sold My Heart to the JunkMan / So Broke up ’61 3705 Al Casey Combo A Cookin’ / Hot Foot ‘61 3706 The Darnell Brothers It's Me / Little Two Face ‘61 3707 Ritchie Hart Vacation TiMe / Her Singing Idol ‘61 3708 Jack Cook Run Boy Run / I Gotta Book ‘61 3709 Ritchie Hart & Heartbeats Do It Twist / Phyllis ‘61 3710 Little Worley and the Drops Who Stole My Girl / You Better Watch Yourself ‘61 3711 Terry Wells Her Song / Terry’s TheMe ‘62 3712 The Prophets Ape / Japanese Twist ‘62 3713 Arv Jenkins Jenny Gaylor / Runnin' Wild (Picture Sleeve) ‘62 3714 Frankie and the Favorites Whirlaway / Phyllis ‘62 3715 The Vice-Roys My Heart / I Need Your Love So Bad Jim Musil ‘62 3716 Ritchie Hart So Far Away From Home / Love ls ‘62 3717 The Versatiles w/ M.M. CoMbo Blue Feelin’ / Just Pretending Jim Musil ‘63 3718 JimMy Grey My World / Late Last Night ‘63 3719 Jody Brian Quartet Drifting HoMe To You / Cabin on the Hill ‘63 3720 Jane Darwin His and Hers / Half A WoMan Jerry Davis/Joe English ‘63 3721 Jack Cook B Walk Another Mile / My Evil Mind ‘63 3722 Johnny Lance C* All About Julie * / Mountain In The Rainbow Jody Reynolds/Floyd RaMsey ‘63 3723 Donny Owens DreaM Girl / My Love ‘63 3724 Larry Rickard & Heart Beats Doctor Love / Lived My Life In Pain ‘63 3725 Brother Zee & Decades Smokey the Bear / Sha-BooM Bang Jim Musil ‘63 3726 Pee Wee Sutton You Don’t Thrill Me / That’s What I DreaMed Last Night ‘64 3727 Don Rutherford D E The PunishMent of Love/Skadawdawreetawrawskrawnskrillyawnskraw(The EskiMo Song) ‘64 3728 Mack Fields I Like To Yodel / O, How The TiMe Does Fly ‘64 3729 Mary Keel ChristMas Is A Season / Dear Mr. -

To Help Flood Victims

08120 z á m JULY 8, 1972 $1.25 á F A 3 BILLBOARD PUBLICATION 1'V SEVENTY -EIGHTH YEAR z The International r,.III Music- RecordTape Newsweekly TAPE /AUDIO /VIDEO PAGE 28 HOT 100 PAGE 56 I C) TOP LP'S PAGES 58, 60 FCC's Ray To Clear NARM Spearheads Drive Payola Air At Forum LOS ANGELES -William B. Ray, chief of the complaints and To Help Flood Victims compliances division of the Federal Communications Commission, By PAUL ACKERMAN will clear the air on the topic of payola as a speaker of the fifth annual Billboard Radio Programming Forum which will be held here NEW YORK-A massive all - ing closely with the record manu- working out these plans in con- Aug. 17 -19 at the Century Plaza Hotel. Ray will be luncheon speaker industry drive to aid record and facturers, vendors of fixtures and junction with representatives of all on Aug. 18. tape retailers whose businesses accessories, even pressing plants industry segments. He indicated have been partially or totally wiped and we are drawing that final decisions would be up Seven other new up a speakers, including new commissioner Ben out by the recent floods is being plan whereby damaged stock and to branches. local distributors. rack - Hooks of the FCC, have been slated for the three -day Forum, the spearheaded by NARM executive fixtures may be replenished at jobbers. rather than a central largest educational radio programming meeting of its kind. Also director Jules Malamud, NARM cost. We are also hopeful that group. speaking will be Paul Drew, programming consultant from Wash- president Dave Press and the or- the victimized businesses will be Overall Plan ington, D.C.; Pat O'Day, general manager of KJR, Seattle; Sonny ganization's board of directors. -

Playlist.Pdf

by Andrew Blendermann www.blenderful.com Frank SINATRA Nat “King” COLE CROONERS All My Tomorrows Angel Eyes (Bennett, Mathis, etc.) All Or Nothing At All Avalon Ain’t That A Kick In The All The Way Ballerina Head The Best Is Yet To Come Darling, Je Vous Aime Call Me Irresponsible The Best Of Everything Beaucoup Catch A Falling Star Chicago (That Toddlin’ For Sentimental Reasons Chances Are Town) Frim-Fram Sauce Cheek To Cheek Come Fly With Me Late, Late Show Dancing On The Ceiling High Hopes L-O-V-E Danke Schoen I Thought About You Mona Lisa Everybody Loves Somebody I'm Gonna Live Till I Die Orange-Colored Sky I Left My Heart In San I’ve Got The World On A Ramblin' Rose Francisco String Route 66 I Wanna Be Around I’ve Got You Under My Skin Smile Let's Get Away From It All In The Wee Small Hours Straighten Up And Fly Right Magic Moments It Was A Very Good Year Sweet Lorraine Mean To Me Just In Time Tenderly Memories Are Made Of This Lady Is A Tramp That Sunday, That Summer Misty Love And Marriage This Can’t Be Love More My Kind Of Town Those Lazy, Hazy, Crazy Once Upon A Time Nancy With The Laughing Face Days Of Summer Papa Loves Mambo Nice 'n' Easy The Very Thought Of You Please Don't Talk About Me One For My Baby (And One Walking My Baby Back When I'm Gone More For The Road) Home Quando, Quando, Quando Second Time Around When I Take My Sugar To Rags To Riches September Song Tea Shadow Of Your Smile Something’s Gotta Give Sway Tender Trap (Love Is The) Teach Me Tonight That’s Life That’s All Time After Time (40’s) Violets For Your Furs Too Close For Comfort Volare Too Marvelous For Words When Sunny Gets Blue Witchcraft You Make Me Feel So Young Young At Heart www.blenderful.com - 1 - Summer 2021 Andrew Blendermann “Blenderful Music” George GERSHWIN Duke ELLINGTON Fats WALLER, But Not For Me Caravan Louis JORDAN, Embraceable You Don’t Get Around Much Louis PRIMA, etc. -

Song Title Artist Album Year

Song Title Artist Album Year #1 Celia Cruz (All I Have To Do Is) Dream Gina West Promo Only - Country Radio - December 1999 (Da Le) Yaleo Guy Lombardo And His Royal Canadians The Fabulous Fifties - Those Wonderful Years (Disc 2) (Don't Fear) The Reaper Nelly Mainstream Radio October 2001 2001 (Ghost) Riders In The Sky The Brian Setzer Orchestra VaVoom 2000 (Goin') Wild For You Baby Ramsey Lewis Trio AM Gold 1965 1990 (Have I Stayed) Too Long At The fair/Look At That Face Linda Ronstadt (Feat. Nelson Riddle and his Orchestra) For Sentimental Reasons 1986 (Have) I Stayed Too Long At The Fair Sarah Vaughn The Sullivan Years-Great Ladies Of Jazz (He's A) Quiet Guy Maureen McGovern Maureen McGovern Sings Gershwin - Naughty Baby (Hot S**T) Country Grammar (Clean Edit W/Effects) Keith Whitley & Lorrie Morgan Greatest Hits 1995 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Pam Tillis Sweetheart's Dance 1994 (I Got Spurs) Jingle, Jangle, Jingle Rod Stewart As Time Goes By...:The Great American Songbook Vol. 2 2003 (I Had Myself A) True Love Nylons, The Rockapella (I Hate) Everything About You Santana Supernatural 1999 (I Just) Died In Your Arms - Cutting Crew Blue Oyster Cult Rough And Rowdy (70s Greatest Rock Hits #7) (I Know) I'm Losing You The Outlows South Rules 70's Greatest Rock Hits Volume 2 (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Bonnie Raitt Bonnie Raitt Collection 1990 (If Loving You Is Wrong)I Don't Want To Be Right Barbra Streisand Just For The Record ... The 60's (Part II) 1991 (If There Was) Any Other Way Rosemary Clooney 70 - A Seventieth Birthday Celebration 1998 (If You Want It) Do It Yourself Darlene Love The Best Of Darlene Love 1992 (I've Been) Searchin' So Long Nelly Promo Only Mainstream Radio - Aug 00 (I've Got To) Stop Thinkin' 'Bout That Devo Casino (Disc 2) 1995 (I've Got) Beginner's Luck Kay Kyser Big Bands In Hi-Fi, Vol 1 - Let's Dance (Disc 2) (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Barbra Streisand Just For The Record ..