Caspase-Mediated Nuclear Pore Complex Trimming in Cell Differentiation and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovery of Endoplasmic Reticulum Calcium Stabilizers to Rescue ER-Stressed Podocytes in Nephrotic Syndrome

Discovery of endoplasmic reticulum calcium stabilizers to rescue ER-stressed podocytes in nephrotic syndrome Sun-Ji Parka, Yeawon Kima, Shyh-Ming Yangb, Mark J. Hendersonb, Wei Yangc, Maria Lindahld, Fumihiko Uranoe, and Ying Maggie Chena,1 aDivision of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63110; bNational Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Rockville, MD 20850; cDepartment of Genetics, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63110; dInstitute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland 00014; and eDivision of Endocrinology, Metabolism, and Lipid Research, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63110 Edited by Martin R. Pollak, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brookline, MA, and approved May 28, 2019 (received for review August 16, 2018) Emerging evidence has established primary nephrotic syndrome activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), which act as proximal (NS), including focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), as a sensors of ER stress. ER stress activates these sensors by inducing primary podocytopathy. Despite the underlying importance of phosphorylation and homodimerization of IRE1α and PERK/ podocyte endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in the pathogenesis of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), as well as relocalization of NS, no treatment currently targets the podocyte ER. In our mono- ATF6 to the Golgi, where it is cleaved by S1P/S2P proteases from genic podocyte ER stress-induced NS/FSGS mouse model, the 90 kDa to the active 50-kDa ATF6 (8), leading to activation of podocyte type 2 ryanodine receptor (RyR2)/calcium release channel their respective downstream transcription factors, spliced XBP1 on the ER was phosphorylated, resulting in ER calcium leak and (XBP1s), ATF4, and p50ATF6 (8–10). -

Towards Therapy for Batten Disease

Towards therapy for Batten disease Mariana Catanho da Silva Vieira MRC Laboratory for Molecular Cell Biology University College London PhD Supervisor: Dr Sara E Mole A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College London September 2014 Declaration I, Mariana Catanho da Silva Vieira, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract The gene underlying the classic neurodegenerative lysosomal storage disorder (LSD) juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (JNCL) in humans, CLN3, encodes a polytopic membrane spanning protein of unknown function. Several studies using simpler models have been performed in order to further understand this protein and its pathological mechanism. Schizosaccharomyces pombe provides an ideal model organism for the study of CLN3 function, due to its simplicity, genetic tractability and the presence of a single orthologue of CLN3 (Btn1p), which exhibits a functional profile comparable to its human counterpart. In this study, this model was used to explore the effect of different mutations in btn1 as well as phenotypes arising from complete deletion of the gene. Different btn1 mutations have different effects on the protein function, underlining different phenotypes and affecting the levels of expression of Btn1p. So far, there is no cure for JNCL and therefore it is of great importance to identify novel lead compounds that can be developed for disease therapy. To identify these compounds, a drug screen with btn1Δ cells based on their sensitivity to cyclosporine A, was developed. Positive hits from the screen were validated and tested for their ability to rescue other specific phenotypes also associated with the loss of btn1. -

Serine Proteases with Altered Sensitivity to Activity-Modulating

(19) & (11) EP 2 045 321 A2 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 08.04.2009 Bulletin 2009/15 C12N 9/00 (2006.01) C12N 15/00 (2006.01) C12Q 1/37 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 09150549.5 (22) Date of filing: 26.05.2006 (84) Designated Contracting States: • Haupts, Ulrich AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR 51519 Odenthal (DE) HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC NL PL PT RO SE SI • Coco, Wayne SK TR 50737 Köln (DE) •Tebbe, Jan (30) Priority: 27.05.2005 EP 05104543 50733 Köln (DE) • Votsmeier, Christian (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in 50259 Pulheim (DE) accordance with Art. 76 EPC: • Scheidig, Andreas 06763303.2 / 1 883 696 50823 Köln (DE) (71) Applicant: Direvo Biotech AG (74) Representative: von Kreisler Selting Werner 50829 Köln (DE) Patentanwälte P.O. Box 10 22 41 (72) Inventors: 50462 Köln (DE) • Koltermann, André 82057 Icking (DE) Remarks: • Kettling, Ulrich This application was filed on 14-01-2009 as a 81477 München (DE) divisional application to the application mentioned under INID code 62. (54) Serine proteases with altered sensitivity to activity-modulating substances (57) The present invention provides variants of ser- screening of the library in the presence of one or several ine proteases of the S1 class with altered sensitivity to activity-modulating substances, selection of variants with one or more activity-modulating substances. A method altered sensitivity to one or several activity-modulating for the generation of such proteases is disclosed, com- substances and isolation of those polynucleotide se- prising the provision of a protease library encoding poly- quences that encode for the selected variants. -

Caspase-12 Antibody A

Revision 1 C 0 2 - t Caspase-12 Antibody a e r o t S Orders: 877-616-CELL (2355) [email protected] Support: 877-678-TECH (8324) 2 0 Web: [email protected] 2 www.cellsignal.com 2 # 3 Trask Lane Danvers Massachusetts 01923 USA For Research Use Only. Not For Use In Diagnostic Procedures. Applications: Reactivity: Sensitivity: MW (kDa): Source: UniProt ID: Entrez-Gene Id: WB M Endogenous 42, 55 Rabbit O08736 12364 Product Usage Information Application Dilution Western Blotting 1:1000 Storage Supplied in 10 mM sodium HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 100 µg/ml BSA and 50% glycerol. Store at –20°C. Do not aliquot the antibody. Specificity / Sensitivity Caspase-12 Antibody detects endogenous levels of full-length caspase-12 protein (55 kDa) and its cleaved product (42 kDa). The antibody does not cross-react with other caspases. Species Reactivity: Mouse Source / Purification Polyclonal antibodies are produced by immunizing animals with a synthetic peptide corresponding to residues surrounding amino acid 158 of mouse caspase-12. Antibodies are purified by protein A and peptide affinity chromatography. Background Caspase-12 is located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). It is responsible for ER stress- induced apoptosis, such as high calcium concentration, low oxygen, and low glucose levels (1,2). One of the mechanisms for caspase-12 activation is related to calpain- mediated cleavage at T132 and K158, both of which are located at the amino-terminal region of caspase-12 (2,3). Caspase-12 also has a putative caspase cleavage site located at the carboxy-terminal region of the protein (3). -

Di-O-Demethylcurcumin Protects SK-N-SH.Pdf

Neurochemistry International 80 (2015) 110–119 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Neurochemistry International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/nci Di-O-demethylcurcumin protects SK-N-SH cells against mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum-mediated apoptotic cell death induced by Aβ25-35 Decha Pinkaew a, Chatchawan Changtam b, Chainarong Tocharus c, Sarinthorn Thummayot c, Apichart Suksamrarn d, Jiraporn Tocharus a,* a Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand b Division of Physical Science, Faculty of Science and Technology, Huachiew Chalermprakiet University, Samutprakarn 10540, Thailand c Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand d Department of Chemistry and Center of Excellence for Innovation in Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Ramkhamhaeng University, Bangkok 10240, Thailand ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative and progressive disorder. The hallmark of pathological Received 2 July 2014 AD is amyloid plaque which is the accumulation of amyloid β (Aβ) in extracellular neuronal cells and Received in revised form 20 October 2014 neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) in neuronal cells, which lead to neurotoxicity via reactive oxygen species Accepted 21 October 2014 (ROS) generation related apoptosis. Loss of synapses and synaptic damage are the best correlates of cog- Available online 24 October 2014 nitive decline in AD. Neuronal cell death is the main cause of brain dysfunction and cognitive impairment. Aβ activates neuronal death via endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and mitochondria apoptosis pathway. Keywords: This study investigated the underlying mechanisms and effects of di-O-demethylcurcumin in prevent- Alzheimer’s disease Amyloid beta ing Aβ-induced apoptosis. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,871,609 B2 Ziff Et Al

US007871609B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,871,609 B2 Ziff et al. (45) Date of Patent: Jan. 18, 2011 (54) SUPPLEMENTS FOR PAIN MANAGEMENT 2006,0040000 A1 2/2006 Gokaraju et al. 2006/0240037 A1 10/2006 Fey et al. (76) Inventors: Sam Ziff, 1617 E. Robinson St., Apt. 2, 2006, O246.115 A1 11/2006 Rueda et al. Orlando, FL (US) 32803; David Ziff, 1822 Hillcrest Dr., Orlando, FL (US) OTHER PUBLICATIONS 328O3 Jurna I. Schmerz, Analgetische und analgesie-potenzietende Wirkung von B-Vitaminen, Medizinische Fakultat der Universitat (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this des Saarlandes, Apr. 20, 1998, pp. 136-141, vol. 12, No. 2. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 Gokhale, Leela B., Curative treatment of primary (spasmodic) U.S.C. 154(b) by 369 days. dysmenorrhoea, Indian J. Med. Res., Apr. 1996, pp. 227-231, vol. 103. (21) Appl. No.: 12/038,534 Kandarkar, et al., Subchronic oral heptotoxicity of turmeric in mice—Histopathological and ultrastructural studies, Indian Journal (22) Filed: Feb. 27, 2008 of Experimental Biology, Jul. 1998, pp. 675-679, vol. 36. Bender, David A. Novel functions of vitamin B6, Proceedings of the (65) Prior Publication Data Nutrition Society, 1994, pp. 625-630, vol. 53. Chandra, et al., Regulation of Immune Responses by Vitamin B6, NY US 2008/O213246A1 Sep. 4, 2008 AcadSci, 1990, pp. 404–423, vol. 585. Trakatellis, et al., Pyridoxine deficiency: new approaches in Related U.S. Application Data immunosuppression and chemotherapy, Postgrad Med J. 1997, pp. 617-622, vol. 73. (60) Provisional application No. -

Caspase-12 Processing and Fragment Translocation Into Nuclei of Tunicamycin-Treated Cells

Cell Death and Differentiation (2002) 9, 1108 ± 1114 ã 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 1350-9047/02 $25.00 www.nature.com/cdd Caspase-12 processing and fragment translocation into nuclei of tunicamycin-treated cells E Fujita1,4, Y Kouroku1,4, A Jimbo1, A Isoai2, K Maruyama3 proteins called IREs1 that lead to the induction of ER stress. and T Momoi*,1 For instance, IRE1-a mediates ER stress signals induced by agents such as tunicamycin, which blocks N-linked protein 2 1 Divisions of Development and Differentiation, National Institute of glycosylation in the ER. Upon activation, IRE1-a can recruit Neuroscience, NCNP, Kodaira, Tokyo, Japan the cytosolic adaptor protein, TNF receptor-associated factor 2 Asahi glass Co., Hasawa-cho, Kanagawa-ku, Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan 2 (TRAF2), which in turn recruits and activates the proximal 3 Department of Pharmacology, Saitama Medical School, Moroyama, Saitama, components of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway. Japan 4 ER stress also leads to the activation of genes possessing a The ®rst two authors contributed equally to this work. 3 * Corresponding author: T Momoi, Division of Development and Differentiation, UPR element in the promoter region. Such genes include the National Institute of Neuroscience, NCNP, Kodaira, Tokyo 187-8502, Japan. Bip/Grp78 protein that increases protein folding in the ER Tel: +81-42-341-2711 Ext 5273; Fax: +81-42-346-1754; lumen. When these stress signals are unable to rescue cells, E-mail: [email protected] the apoptotic pathway is activated. However, little is known about the molecular mechanism of cell death induced by ER Received 23.1.02; revised 10.5.02; accepted 13.5.02 stress. -

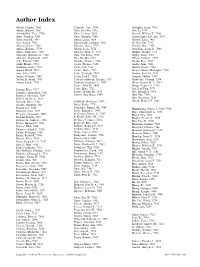

Author Index

Author Index A˚ brink, Magnus, 7681 Cemerski, Saso, 7394 Gallagher, Grant, 7302 Adachi, Roberto, 7681 Chen, Jian-Xia, 7435 Gan, Li, 7573 Afonyushkin, Taras, 7706 Chen, Lieping, 7654 Garrard, William T., 7544 Alder, Jonathan, 7161 Chen, Shuzhen, 7699 Garrett-Sinha, Lee Ann, 7374 Allen, Paul M., 7487 Cheng, Liang, 7654 Garzetti, Livia, 7467 Alon, Ronen, 7394 Chennareddi, Lakshmi, 7262 Ge, Bao-Xue, 7435 Alvarez, Xavier, 7340 Chiarini, Marco, 7713 Geadah, Marc, 7374 Amano, Keishiro, 7739 Chieffi, Paolo, 7474 Geutskens, Sacha B., 7691 Amara, Rama Rao, 7262 Chilvers, Mark A., 7731 Ghidini, Claudia, 7713 Anderson, Shannon M., 7146 Chin, Shu Shien, 7374 Gigley, Jason, 7663 Anderton, Stephen M., 7235 Cho, Dae-Ho, 7274 Gilbert, Sarah C., 7583 Aoki, Takashi, 7507 Choubey, Divaker, 7385 Giorda, Ezio, 7293 Araki, Mariko, 7739 Ciucci, Thomas, 7165 Gocke, Anne, 7161 Aranburu, Alaitz, 7293 Civin, Curt, 7161 Goebel, Nicole, 7180 Arnold, Bernd, 7518 Clerici, Mario, 7723 Gomez, Manuel Rodriguez, 7180 Asai, Akira, 7174 Coch, Christoph, 7367 Gordon, Scott M., 7151 Augier, Se´verine, 7165 Coffer, Paul J., 7252 Gorman, Shelley, 7207 Austen, K. Frank, 7681 Conforti-Andreoni, Cristina, 7317 Grabovsky, Valentin, 7394 Azuma, Eiichi, 7739 Constant, Stephanie L., 7663 Green, Francis H. Y., 7413 Cooper, Max D., 7405 Grupp, Stephan A., 7151 Badami, Ester, 7317 Corey, Mary, 7731 Gui, Jian-Fang, 7573 Balandya, Emmanuel, 7596 Cortes, Claudia M., 7633 Guo, Mingzhou, 7654 Ballatore, Giovanna, 7293 Cuervo, Ana Maria, 7349 Guo, Yun, 7330 Balsley, Molly A., 7663 Guo, Zhenhong, -

Caspase 12 Polyclonal Antibody Catalog Number:55238-1-AP 60 Publications

For Research Use Only Caspase 12 Polyclonal antibody www.ptglab.com Catalog Number:55238-1-AP 60 Publications Catalog Number: GenBank Accession Number: Purification Method: Basic Information 55238-1-AP NR_000035 Antigen affinity purification Size: GeneID (NCBI): Recommended Dilutions: 150ul , Concentration: 550 μg/ml by 120329 WB 1:500-1:2000 Nanodrop and 400 μg/ml by Bradford Full Name: IP 0.5-4.0 ug for IP and 1:500-1:2000 method using BSA as the standard; caspase 12 (gene/pseudogene) for WB Source: IHC 1:50-1:500 Calculated MW: IF 1:50-1:500 Rabbit 39 kDa Isotype: Observed MW: IgG 36-42 kDa, 50 kDa Applications Tested Applications: Positive Controls: IF, IHC, IP, WB,ELISA WB : HEK-293 cells, multi-cells Cited Applications: IP : HEK-293 cells, IF, IHC, WB IHC : human prostate hyperplasia tissue, human heart Species Specificity: tissue human Cited Species: IF : HeLa cells, hamster, human Note-IHC: suggested antigen retrieval with TE buffer pH 9.0; (*) Alternatively, antigen retrieval may be performed with citrate buffer pH 6.0 Caspase 12 is an enzyme known as a cysteine protease. It belongs to a family of enzymes called caspases that Background Information cleave their substrates at C-terminal aspartic acid residues. It is most highly related to members of the ICE subfamily of caspases that process inflammatory cytokines. Caspase-12 is located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). It is responsible for ER-stress-induced apoptosis, such as high calcium concentration, low oxygen and low glucose levels. Caspase-12 Antibody detects endogenous levels of full-length caspase-12 protein (50 kDa) and its cleaved product (40-44 kDa). -

R&D Systems Products for Neuroscience Research

R&D Systems Tools for Cell Biology Research™ R&D Systems Products for Neuroscience Research ON THE COVER This illustration was featured in the Cytokine Bulletin (2010, Issue 1). TLR2 IL-6 IL-6 R MOG IL-21 R TGF-β R STAT3 Dendritic TGF-β Cell STAT3 Batf, RORγt IL-23 Batf RORγt Th17 Cell IL-23 R IL-17 JunB Batf RORγt IL-17 NO Myelin TNF-α Axon MMPs Macrophages Neuron Oligodendrocyte Prolonged production of IL-17 by Th17 cells is dependent on the transcription factor Batf. Recent studies suggest that prolonged production of IL-17 by Th17 cells is dependent on the synergistic actions of the RORt and Batf-JunB transcription factors. These fi ndings may have implications for Th17-related autoimmune disorders such as multiple sclerosis. Following induction of autoimmune conditions in mice using myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) immunization, diff erentiated Th17 cells secrete proinfl ammatory cytokines, and activated macrophages destroy myelin and damage oligodendrocytes. It remains to be determined whether the induction of Batf expression is dependent on STAT3 in Th17 cells, and whether an interaction between Batf and Irf4 or Ahr is required to promote the respective induction of IL-21 and IL-22. Schraml, B.U. et al. (2009) Nature 460:405. To request the most recent issue of the Cytokine Bulletin and other R&D Systems literature please visit www.RnDSystems.com/go/Request R&D Systems Tools for Cell Biology Research™ R&D Systems Cytokine Bulletin Cytokine BULLETIN 2011 | Issue 2 Adipose Tissue INSIDE s)NFLAMMATION s$ECREASEDADIPOGENESIS -

A Genomic Analysis of Rat Proteases and Protease Inhibitors

A genomic analysis of rat proteases and protease inhibitors Xose S. Puente and Carlos López-Otín Departamento de Bioquímica y Biología Molecular, Facultad de Medicina, Instituto Universitario de Oncología, Universidad de Oviedo, 33006-Oviedo, Spain Send correspondence to: Carlos López-Otín Departamento de Bioquímica y Biología Molecular Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Oviedo 33006 Oviedo-SPAIN Tel. 34-985-104201; Fax: 34-985-103564 E-mail: [email protected] Proteases perform fundamental roles in multiple biological processes and are associated with a growing number of pathological conditions that involve abnormal or deficient functions of these enzymes. The availability of the rat genome sequence has opened the possibility to perform a global analysis of the complete protease repertoire or degradome of this model organism. The rat degradome consists of at least 626 proteases and homologs, which are distributed into five catalytic classes: 24 aspartic, 160 cysteine, 192 metallo, 221 serine, and 29 threonine proteases. Overall, this distribution is similar to that of the mouse degradome, but significatively more complex than that corresponding to the human degradome composed of 561 proteases and homologs. This increased complexity of the rat protease complement mainly derives from the expansion of several gene families including placental cathepsins, testases, kallikreins and hematopoietic serine proteases, involved in reproductive or immunological functions. These protease families have also evolved differently in the rat and mouse genomes and may contribute to explain some functional differences between these two closely related species. Likewise, genomic analysis of rat protease inhibitors has shown some differences with the mouse protease inhibitor complement and the marked expansion of families of cysteine and serine protease inhibitors in rat and mouse with respect to human. -

Apoptosis in Retinal Degeneration Involves Cross-Talk Between Apoptosis-Inducing Factor (AIF) and Caspase-12 and Is Blocked by Calpain Inhibitors

Apoptosis in retinal degeneration involves cross-talk between apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) and caspase-12 and is blocked by calpain inhibitors Daniela Sanges*, Antonella Comitato*, Roberta Tammaro*, and Valeria Marigo*†‡ *Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine (TIGEM), 80131 Naples, Italy; and †Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, 41100 Modena, Italy Edited by Jeremy Nathans, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, and approved September 21, 2006 (received for review July 24, 2006) Molecular mechanisms underlying apoptosis in retinitis pigmen- mitochondria is regulated by -calpain (18) and can occur inde- tosa, as in other neurodegenerative diseases, are still elusive, and pendently from cytochrome c release (19). this fact hampers the development of a cure for this blinding In this study, we demonstrate a direct correlation of increased disease. We show that two apoptotic pathways, one from the intracellular Ca2ϩ, calpain activation, and nuclear translocation of mitochondrion and one from the endoplasmic reticulum, are co- AIF and caspase-12 in apoptotic photoreceptors. We also show that activated during the degenerative process in an animal model of AIF plays the key role in apoptosis activation. Finally, we provide retinitis pigmentosa, the rd1 mouse. We found that both AIF and evidences that treatment with calpain inhibitors is able to block caspase-12 translocate to the nucleus of dying photoreceptors in activation of AIF and caspase-12 and, consequently, apoptosis in vivo and in an in vitro cellular model. Translocation of both vitro and in vivo. apoptotic factors depends on changes in intracellular calcium homeostasis and on calpain activity.