Resolving the Subsidiary Director's Dilemma Eric J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resume Dop Jackson Hunt

2018-09-24 | Page 1 [ 2 ] Resume DoP Jackson Hunt Feature Film The Standoff at Sparrow Creek, Dir: Henry Dunham Short Films Jellywolf, Dir: Alma Har’el Lifeboat, Dir: Lorraine Nicholson Gerty, Dir: Dori Oskowitz Blackout, Dir: Dori Oskowitz Commercials Absolut Vodka, Airwick, Apple, Audi, Beats, Bank of Montreal, Black XS Perfume, Beats by Dre, BMO, Chanel/ID Magazine, Com hem, Converse, Facebook, Federal Student Aid: PSA, Goodwill: PSA, Google, Google Glass, Google Pixel, H&M, Head & Shoulders, Hershey’s, Honey Maid, i-D Magazine, John Lewis, Kiehls, LA Tourism & Convention Board, Lacoste, Levis, Lululemon, McDonalds, Nationwide, Nike, Paco Rabanne, P & G Secret, Rapha, River Island: SS15, Rosetta Stone, Stella McCartney, Telekom, Toyota, Unilever Project Sunlight, Uniqlo, Vauxhall: Corsa, Virgin Atlantic, Woolworths feat. Pharrell, World Vision: PSA Music Videos 2Chainz feat. Pharrell, Ambrosius, Angel Haze, Banks, Bastille, Belly, Ben Booker, Best Coast, Beyonce, Broods, Bryson Tiller, Cliff Dweller, Carly Rae Jepsen, Chrome Canyon, Coasts, Dj Cassidy ft. R Kelly, Hilary Duff, How to Destroy Angels, Hundred in the Hands, Indiana, Jake Bugg, Jamie XX, Jesse Boykins III, Jill Scott feat. Robert Glasper, Lawrence Rothman, Lawson, London Grammar, Major Lazer, Manchester Orchestra, Marsha, Mary J. Blige, Mary Lambert, Meghan Trainor, Travis Scott, Nick Jonas, Passion Pit, Purity Ring, RAC feat. Penguin Prison, Rita Ora, Sam Hunt, Selena Gomez, Skylar Grey, Solange, Steve Aoki, Sub Focus, The hundred in the Hands, The 1975, The War on Drugs, -

City and Colour with Guest Shakey Graves

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 106.7 THE DRIVE PRESENTS CITY AND COLOUR WITH GUEST SHAKEY GRAVES MONDAY, JUNE 6, 2016 ENMAX CENTRIUM, WESTERNER PARK – RED DEER, AB Doors: 6:30PM Show: 7:30PM TICKETS ON SALE FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 27 @ 10AM www.livenation.com Charge by Phone 1-855-985-5000 Tickets also available at all Ticketmaster Outlets Tickets (incl. GST) $35.00, $45.00, $59.50 (Plus FMF & Service charges) **RESERVED SEATING / ALL AGES** CITY AND COLOUR ANNOUNCES 2016 CANADIAN TOUR IN SUPPORT OF NEW LP IF I SHOULD GO BEFORE YOU DEBUTS INCLUDE #1 in CANADA + #16 on US BILLBOARD 200 + #5 in AUSTRALIA WATCH THE VIDEO FOR “Wasted Love” FROM DIRECTOR X HERE “...tells a story with a sincerity and fluency that is truly masterful.”—BBC “...moving, melodramatic songs delivered with candor and confidence by Mr. Green in a sweet, soaring voice. An excellent guitarist, he’s equally adept in a sparse solo folk setting and out in front of powerhouse players...” — The Wall Street Journal “Moody, magnificent and damn close to a masterpiece, this might be the finest album of Green’s career.”— Toronto Sun/Sun Media “…the strongest, most consistent set of songs City and Colour has produced” —Rolling Stone Australia City and Colour, acclaimed singer, songwriter and performer Dallas Green, has announced a Canadian tour for 2016. The tour, in support of Green’s latest album If I Should Go Before You, kicks off in Kelowna on June 2, and wraps up in Montreal on June 20, 2016 (full routing below). Supporting City and Colour on the tour is Austin’s Shakey Graves. -

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) Management Directive 715 (EEO Program Status) Report Fiscal Year 2019

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) Management Directive 715 (EEO Program Status) Report Fiscal Year 2019 Six Essential Elements of a Model EEO Program Prepared by the Office of Equal Opportunity Programs United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE 1849 C Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20240 IN REPLY REFER TO: P4217 (2740) DEC 1 7 2019 Memorandum To: Director, Office of Civil Rights, Office of the Secretary, DOI Thru: Deputy Director, Operations Exercising the Authority of the Director x -------- From: Chief, Office of Equal Opportunity Programs Subject: MD-715 EEO Program Status Report for FY 2019 Please find the attached annual MD-715 Executive Summary Report for FY 2019 for the National Park Service. The National Park Service is focused on creating a workplace environment that embraces and celebrates the diversity and multiculturalism of the people it serves. This goal is specified in the Director’s Call to Action, action item 36, which calls for the development “of a workforce that values diversity and an inclusive work environment so that the Service can recruit, hire, and retain diverse employees.” If you have any questions regarding this report, please contact Cleveland Williams, Affirmative Employment Program Manager at (202) 354-1857. cc: Kimberly Ly, Compliance and Programs Division, Office of Civil Rights Department of the Interior Acquanetta Newson, Compliance and Programs Division, Office of Civil Rights Department of the Interior ti/uai fjzfwjrffti -

Script to Screen a ONE DAY FILM INTENSIVE Program Guidelines

Script to Screen A ONE DAY FILM INTENSIVE Program Guidelines IMPORTANT DATES APPLICATION DEADLINE Tuesday, January 2, 2018 – 11:59 pm SCRIPT TO SCREEN WORKSHOP When: Friday, Feb. 16, 2018 (if selected, applicant must be able to attend on this day) Where: Campus of Fayetteville State University Time: 8:30 am – 5 pm OVERVIEW PROGRAM PURPOSE The purpose of Script to Screen is to provide students who are exploring a career in the film industry an opportunity to experience the many facets of film production under the guidance of a professional active in the industry. In this one-day film production intensive with noted writer, producer and Jamel "Mel City" Thornton. Students in grades 9-12 will learn theory and application in six key areas of film production: • Development and scriptwriting • Pre-production • Production • Wrap • Post-Production • Pitch and shopping distribution ABOUT MEL CITY Mel City got his start in the industry on Spike Lee’s infamous He Got Game. His extensive resume includes work on OX’s hit television series New York Undercover; Belly; countless music videos for artists such as DMX, The Lox, Ja Rule, Mobb Deep, Sean “Diddy” Combs, and Janet Jackson. Mel City has also worked with highly sought after directors like Chris Robinson, Director X (formerly Little X), Dave Myers and Benny Boom and is currently producing FLINT 6, a fictional-biopic which confronts the Flint Water Crisis head on. An Army veteran, Mel City holds a B.S. in Communication Arts & Mass Communication from St. John’s University, attended Thurgood Marshall School of Law (Houston, Texas) and is currently studying for the New York Uniform Bar Exam. -

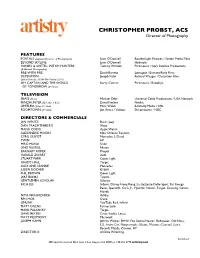

CHRISTOPHER PROBST, ASC Director of Photography

CHRISTOPHER PROBST, ASC Director of Photography FEATURES WAR OF THE WORLDS Rich Lee Universal / Staying Safe Productions PORTALS (Segment Director of Photography) Liam O’Donnell BoulderLight Pictures / Screen Media Films BEYOND SKYLINE Liam O’Donnell Hydraulx HANSEL & GRETEL: WITCH HUNTERS Tommy Wirkola Paramount / Gary Sanchez Productions (Additional Photography) FIRE WITH FIRE David Barrett Lionsgate / Emmett/Furla Films DETENTION Joseph Kahn Richard Weager / Detention Films Official Selection, SXSW Film Festival (2011) SKY CAPTAIN AND THE WORLD Kerry Conran Paramount / Brooklyn OF TOMORROW (2nd Unit) TELEVISION ERASE (Pilot) Michael Offer Universal Cable Productions / USA Network MINDHUNTER (Episodes 1 & 2) David Fincher Netflix LIMITLESS (Pilot, 2nd Unit) Marc Webb Relativity Media / CBS BOOMTOWN (2nd Unit) Jon Avnet / Various Dreamworks / NBC DIRECTORS & COMMERCIALS JAN WENTZ Buick, Jeep DAN TRACHTENBERG Xbox, Playstation MANU COSSU Apple Watch ALEXANDRE MOORS New Orleans Tourism CYRIL GUYOT Mercedes, L’Oreal TWIN HP HIRO MURAI Scion LINO RUSSELL Nissan BARNABY ROPER Propel HARALD ZWART Audi STUART PARR Coors Light GRADY HALL Target ALEX AND LEANNE Mercedes JULIEN ROCHER K1664 PHIL BROWN Coors Light JAKE BANKS Toyota GENTLEMEN SCHOLAR Udacity RICH LEE Subaru, Disney Hong Kong, La Gazzetto Dello Sport, Eni Energy, Beats, Special K, Carls Jr., Hyundai, Nissan, Target, Samsung, Sunosi, Honda NIMA NOURIZADEH Adidas BEN MOR Cisco GMUNK YouTube Red, Infiniti MATT OGENS Farmer John MARK PALANSKY Target DAVE MEYERS Ciroc Vodka, Lexus MATT -

Media Release

MEDIA RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ANDREW FEINSTEIN, MARTY SYJUCO ATTEND REELWORLD FILM FESTIVALTO SUPPORT ‘MEDIA FOR IMPACT’ REELWORLD 2016 HARNESSES THE POWER OF FILM AS A FORCE FOR SOCIAL GOOD TORONTO, ON (September 21, 2016) – Reelworld Film Festival returns for its 16th year featuring critically acclaimed feature films, shorts, documentaries, virtual reality films, games and more — all dedicated to harnessing the visual medium as a force for social good. The festival, which runs October 12–16 at Harbourfront Centre (235 Queens Quay West), launches with a one-day breakout conference on October 12 entitled Media for Impact ; a first-time ever experience that brings together organizations behind acclaimed films such as VIRUNGA, GIRLS RISING, BULLY, THE SQUARE and GASLAND. Supporting the festival’s multiple causes are critically-acclaimed author of “ The Shadow World: Inside the Global Arms Trade” Andrew Feinstein and award-winning filmmaker Marty Syjuco who will be in attendance and available for media opportunities before the festival. New this year, Reelworld has created a Conversation Room where audiences congregate after each screening to meet with activists, nonprofits and leaders working directly on the issues addressed in each of the films — giving attendees the opportunity to make change in the real world. “With so much turmoil, conflict and uncertainty in our world today Reelworld is focused on showcasing stories that offer solutions and build movement towards positive change,” says Gave Lindo, Reelworld Executive Director -

CHRISTOPHER PROBST, ACS Director of Photography

CHRISTOPHER PROBST, ACS Director of Photography FEATURES PORTALS (Segment Director of Photography) Liam O’Donnell BoulderLight Pictures / Screen Media Films BEYOND SKYLINE Liam O’Donnell Hydraulx HANSEL & GRETEL: WITCH HUNTERS Tommy Wirkola Paramount / Gary Sanchez Productions (Additional Photography) FIRE WITH FIRE David Barrett Lionsgate / Emmett/Furla Films DETENTION Joseph Kahn Richard Weager / Detention Films Official Selection, SXSW Film Festival (2011) SKY CAPTAIN AND THE WORLD Kerry Conran Paramount / Brooklyn OF TOMORROW (2nd Unit) TELEVISION ERASE (Pilot) Michael Offer Universal Cable Productions / USA Network MINDHUNTER (Episodes 1 & 2) David Fincher Netflix LIMITLESS (Pilot, 2nd Unit) Marc Webb Relativity Media / CBS BOOMTOWN (2nd Unit) Jon Avnet / Various Dreamworks / NBC DIRECTORS & COMMERCIALS JAN WENTZ Buick, Jeep DAN TRACHTENBERG Xbox MANU COSSU Apple Watch ALEXANDRE MOORS New Orleans Tourism CYRIL GUYOT Mercedes, L’Oreal TWIN HP HIRO MURAI Scion LINO RUSSELL Nissan BARNABY ROPER Propel HARALD ZWART Audi STUART PARR Coors Light GRADY HALL Target ALEX AND LEANNE Mercedes JULIEN ROCHER K1664 PHIL BROWN Coors Light JAKE BANKS Toyota GENTLEMEN SCHOLAR Udacity RICH LEE Subaru, Disney Hong Kong, La Gazzetto Dello Sport, Eni Energy, Beats, Special K, Carls Jr., Hyundai, Nissan, Target, Samsung, Sunosi, Honda NIMA NOURIZADEH Adidas BEN MOR Cisco GMUNK YouTube Red, Infiniti MATT OGENS Farmer John MARK PALANSKY Target DAVE MEYERS Ciroc Vodka, Lexus MATT PIEDMONT Microsoft JOSEPH KAHN Johnny Walker, BMW, Fox Sports/Nascar, Budweiser, -

New Monuments Dance & Film Production Blends Art & Activism

New Monuments dance & film production blends art & activism All-star cast of IBPOC creatives including Julien Christian Lutz pka DIRECTOR X, Tanisha Scott & Umbereen Inayet re-imagine the future Toronto, ON (June 15th, 2021) - Canadian Stage and Luminato Festival Toronto team up to present New Monuments, an original dance and film production featuring over 40 of Toronto's leading IBPOC dance- makers and an all-star cast of multi-disciplinary, award-winning, Toronto- bred creative talents, which will have its world premiere at Luminato Festival Toronto, streaming on CBC Gem on October 15th. Co-produced by Canadian Stage and Luminato Festival Toronto, and conceived and curated by Toronto's iconic, Grammy nominated, multiple award-winning director and installation artist Julien Christian Lutz pka DIRECTOR X (Drake, Rihanna, Rosalia, Superfly movie) with award-winning artistic producer and curator Umbereen Inayet (Nuit Blanche Toronto, Awakenings, TEDx) alongside visionary three-time MTV VMA-nominated Tanisha Scott (Beyoncé, Sean Paul) as lead choreographer, New Monuments comes to life on the shore of Lake Ontario, through the talents of Toronto-area dance companies in a cathartic story that takes us from the beginning of colonization to a more hopeful and equitable future. “In this new civil rights movement that we find ourselves in, New Monuments is a work of art that uses movement to tell a story. It shows how the subjugation that’s happening now, is tied to subjugation that happened in the 1800s,” explains co-curator Umbereen Inayet. “It’s a catalyst for change, a place for healing and catharsis, and it actually asks us what we want to take into the new world, and what we want to leave behind”. -

Simon Shohet, Csc | D Irector of Photography

SIMON SHOHET, CSC | D IRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY FEATURE FILMS/TELEVISION (Select Credits): ZAK’S HAUNTED MUSEUM (TV Series – Season 1) Various Discovery+/Cream Productions HISTORY ERASED (TV Series – Season 3) Various History Channel/Cream Productions AGE OF SAMURAI: BATTLE FOR JAPAN (TV Series) Simon George Netflix/Cream Productions/Blue Ant Media MAJIC (Feature Film) Erin Berry Banned For Life Productions KIDS ON (Web Series) Nolan Sarner CBC/Touchpoint Films MOTIVES AND MURDERS (TV Series) Various Cineflix/ID Discovery NOWHERE TO HIDE (TV Series - Seasons 1 & 2) Marc Riccardelli Cineflix/ID Discovery COLLISION COURSE (TV Series - Season 1) Gary Lang Muse Entertainment WEIRD OR WHAT? (TV Series - Seasons 1 & 2) Stephen Scott Cineflix URBAN LEGENDS (TV Series - Season 3) Stephen Scott Cineflix HOW MACHINES WORK (TV Series) Gary Lang Cream Productions BITTEN (Feature Film) Harvey Glazer Peace Arch Ent/RHI SHORT FILMS & DOCUMENTARIES (Select Credits): TRIUMPH: ROCK & ROLL MACHINE (Documentary) Marc Ricciardelli Banger Films FADING Kobe Ntiri Citylife Film Project THE REAL SHERLOCK Gary Lang Storyline Entertainment ROSIE TAKE THE TRAIN Stephen Scott Fireboy Films/ Bravo!FACT DINNER DATE Annie Bradley CFC MUSIC VIDEOS (Select Credits): BEDOUIN SOUNDCLASH – WALLS FALL DOWN HOLLERADO – I GOT YOU JAMES BARKER BAND - CHILLS RIHANNA FT. DRAKE – WORK (2nd Unit) SHAWN HOOK - RELAPSE GLORIOUS SONS – WHITE NOISE JOEL PLASKETT – FASHIONABLE PEOPLE STARS – BACKLINES TERRI CLARK – SOME SONGS KARDINAL OFFISHALL – EVERYDAY RUDEBOY K.I.D – TAKER STEREOS – -

Omer-February-2013.Pdf

the Volume 32, 31, Number Number 6 7 MarchFebruary 2012 2013 TEMPLE BETH ABRAHAM AdarShevat/Adar / Nisan 5773 5772 R i Pu M directory TEMPLE BETH ABRAHAM Services Schedule is proud to support the Conservative Movement by Services/ Time Location affiliating with The United Synagogue of Conservative Monday & Thursday Judaism. Morning Minyan Chapel 8:00 a.m. Friday Evening (Kabbalat Shabbat) Chapel 6:15 p.m. Advertising Policy: Anyone may sponsor an issue of The Omer and receive a dedication for their business or loved one. Contact us for details. We do Shabbat Morning Sanctuary 9:30 a.m. not accept outside or paid advertising. The Omer is published on paper that is 30% post-consumer fibers. Candle Lighting (Friday) The Omer (USPS 020299) is published monthly except July and August February 1 5:14 p.m. by Congregation Beth Abraham, 336 Euclid Avenue, Oakland, CA 94610. February 8 5:22 p.m. Periodicals Postage Paid at Oakland, CA. February 15 5:30 p.m. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to The Omer, c/o Temple Beth February 22 5:37 p.m. Abraham, 336 Euclid Avenue, Oakland, CA 94610-3232. © 2013. Temple Beth Abraham. The Omer is published by Temple Beth Abraham, a non-profit, located at Torah Portions (Saturday) 336 Euclid Avenue, Oakland, CA 94610; telephone 510-832-0936. It is February 2 Yitro published monthly except for the months of July and August for a total of February 9 Mishpatim ten issues per annum. It is sent as a requester publication and there is no February 16 T’rumah paid distribution. -

Spotify Applauds New Bill in Congress That Would Oust Apple's App Store

Bulletin YOUR DAILY ENTERTAINMENT NEWS UPDATE AUGUST 12, 2021 Page 1 of 36 INSIDE Spotify Applauds New Bill in • Kris Wu’s Career in Congress That Would Oust Apple’s Jeopardy as China Cracks Down on App Store Tax ‘Tainted Artists’ BY TATIANA CIRISANO • AEG Presents Will Require Fans and Employees to A new bipartisan bill introduced Wednesday (Aug. in holding Apple and other gatekeeper platforms Be Vaccinated 11) aims to crack down on the so-called “Apple Tax” accountable for their unfair and anti-competitive that developers pay to list their apps on Apple and practices.” Spotify has been one of the most vocal crit- • Kanye West’s Google’s app stores, with Spotify among the bill’s ics of Apple’s App Store system, calling its tax on Latest ‘Donda’ Event Is Most-Watched vocal supporters. in-app purchases “discriminatory” and even accusing Apple Music The Open App Markets Act, led by Sens. Marsha Apple — which of course has its own streaming ser- Livestream Ever Blackburn (R-Tenn.), Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) vice, Apple Music — of rejecting bug fixes and other and Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), intends to protect enhancements to Spotify’s product. • Pop, R&B and Love Songs: The State of developers and bring more competition to the app store “These platforms control more commerce, informa- the Billboard Hot market. Currently, developers must pay Apple and tion, and communication than ever before, and the 100’s Top 10 in the Google between 15% and 30% of revenue made through power they exercise has huge economic and societal First Half of 2021 in-app purchases in order to list their apps on the com- implications. -

The Music Video: from Popular Music to Film and Digital Media

MUSC 499: The Music Video: From Popular Music to Film and Digital Media University of Southern California, Spring 2014 Wednesdays, 6:00pm-9pm THH 202 Instructor: Dr. Richard Brown [email protected] www.richardhbrownjr.com Course Description: Since its emergence in the late 1970s, the music video has become the dominant means of advertising popular music and musicians, as well as one of the most influential multimedia genres in history. Music videos have affected aesthetic style in a wide range of film and television genres, introducing experimental and avant-garde techniques to a mass audience. Because most music videos last only a few minutes, it is difficult to make sense of their often-conflicting images, sounds, and messages. This course challenges participants to read music videos as texts by engaging with their visual and auditory materials. We will explore how the gender, race, and class of video participants shapes meaning, as well as how pacing and editing contribute to (or detract from) a narrative flow. We will also consider the music video in relation to notions of stardom and celebrity, and will speculate on the future of the music video amid drastic changes in the production and marketing of media. The second portion of the course applies these analytical skills to a wide variety of media, including video games, live concert films, film and television music placements, television title sequences and end credits, user generated content, YouTube, remixes and more. Course Materials: There is one required textbook available for free via USC’s electronic Ebook access: Carol Vernallis’ Experiencing Music Video: Aesthetics and Cultural Context (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004).