Inter-CESTI: Methodological and Technical Feedbacks on Hardware Devices Evaluations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dsview User Guide V0.99

DSView User Guide v0.99 Revision History The following table shows the revision history for this document. Date(DD/MM/YY) Version Revision 30/05/18 V0.99 release for DSView v0.99 19/07/17 v0.98 release for DSView v0.98 08/09/16 v0.96 Initial release for DSView v0.96 1 www.dreamsourcelab.com Contents 1 Overview ................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 4 1.2 Download .................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Installing DSView ..................................................................................... 4 1.3.1 Operating System ............................................................................... 4 1.3.2 Recommended Minimum Hardware .................................................. 4 1.3.3 How to Install ..................................................................................... 5 1.4 User Interface ............................................................................................ 8 2 Logic Analyzer ........................................................................................................ 9 2.1 Hardware Connection ............................................................................... 9 2.2 Hardware Options ................................................................................... 11 2.2.1 Mode ............................................................................................... -

Design of a UAV-Based Radio Receiver for Avalanche Beacon Detection Using Software Defined Radio and Signal Processing

UPTEC F19 003 Examensarbete 30 hp Februari 2019 Design of a UAV-based radio receiver for avalanche beacon detection using software defined radio and signal processing Richard Hedlund Abstract Design of a UAV-based radio receiver for avalanche beacon detection using software defined radio and signal processing Richard Hedlund Teknisk- naturvetenskaplig fakultet UTH-enheten A fully functional proof of concept radio receiver for detecting avalanche beacons at the frequency 457 kHz was constructed in the work of this master thesis. The radio Besöksadress: receiver is intended to be mounted on an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV or drone) Ångströmlaboratoriet Lägerhyddsvägen 1 and used to aid the mountain rescue teams by reducing the rescue time in finding Hus 4, Plan 0 avalanche victims carrying a transmitting beacon. The main parts of this master thesis involved hardware requirement analysis, software development, digital signal Postadress: processing and wireless communications. Box 536 751 21 Uppsala The radio receiver was customized to receive low power signal levels because Telefon: magnetic antennas are used and the avalanche beacon will operate in the reactive near 018 – 471 30 03 field of the radio receiver. Noise from external sources has a significant impact on the Telefax: performance of the radio receiver. 018 – 471 30 00 This master thesis allows for straightforward further development and refining of the Hemsida: radio receiver due to the flexibility of the used open-source software development kit http://www.teknat.uu.se/student GNU Radio where the digital signal processing was performed. Handledare: Johan Tenstam Ämnesgranskare: Mikael Sternad Examinator: Tomas Nyberg ISSN: 1401-5757, UPTEC F19 003 Populärvetenskaplig sammanfattning I detta examensarbete har en fullt funktionell "proof of concept" radiomottagare för de- tektering av lavintransceivers på frekvensen 457 kHz konstruerats. -

Picoscope 3000 Series User Guide 2 Introduction

Welcome 1 1 Welcome The PicoScope 3000 Series of PC Oscilloscopes from Pico Technology is a range of high-specification, real-time measuring instruments that connect to the USB port of your computer. The oscilloscopes obtain their power supply through the USB cable, so they do not need an additional power supply and are therefore highly portable. The 3000 Series consists of two ranges: General-purpose range (PicoScope 3204, 3205 and 3206 variants) High-precision range (PicoScope 3224 and 3424 variants) With the PicoScope software you can use PicoScope 3000 Series PC Oscilloscopes as oscilloscopes and spectrum analysers; and with the PicoLog software you can use them as data loggers. Alternatively, using the API functions, 16 you can develop your own programs to collect and analyse data from the oscilloscope. A typical PicoScope 3000 Series PC Oscilloscope is supplied with the following items: USB cable, for use with USB 1.1 and 2.0 ports Software and Reference CD Installation Guide Copyright 2006-7 Pico Technology Limited. All rights reserved. PS3000044-2 2 PicoScope 3000 Series User Guide 2 Introduction 2.1 Safety symbols Symbol 1: Warning Triangle This symbol indicates that a safety hazard exists on the indicated connections if correct precautions are not taken. Read all safety documentation associated with the product before using it. Symbol 2: Equipotential This symbol indicates that the outer shells of the indicated BNC connectors are all at the same potential (shorted together). You must therefore take necessary precautions to avoid applying a potential across the return connections of the indicated BNC terminals as this may cause a large current to flow, resulting in damage to the product and/or connected equipment. -

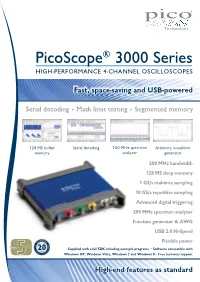

Picoscope® 3000 Series HIGH-PERFORMANCE 4-CHANNEL OSCILLOSCOPES

PicoScope® 3000 Series HIGH-PERFORMANCE 4-CHANNEL OSCILLOSCOPES Fast, space-saving and USB-powered Serial decoding • Mask limit testing • Segmented memory 128 MS buffer Serial decoding 200 MHz spectrum Arbitrary waveform memory analyzer generator 200 MHz bandwidth 128 MS deep memory 1 GS/s real-time sampling 10 GS/s repetitive sampling Advanced digital triggering 200 MHz spectrum analyzer Function generator & AWG USB 2.0 Hi-Speed Flexible power YE AR Supplied with a full SDK including example programs • Software compatible with Windows XP, Windows Vista, Windows 7 and Windows 8• Free technical support High-end features as standard PicoScope 3000 Series 4-Channel Oscilloscopes PicoScope: power, portability and versatility Digital triggering Pico Technology continues to push the limits of USB-powered oscilloscopes. Most digital oscilloscopes sold today still use an analog trigger architecture The new PicoScope 3000 Series offers the highest performance available based on comparators. This can cause time and amplitude errors that from any USB-powered oscilloscope on cannot always be calibrated out. The use of comparators often limits the the market today. trigger sensitivity at high bandwidths and can also create a long trigger The PicoScope 3000 Series has the power “re-arm” delay. and performance for many applications, Since 1991 we have been pioneering the use of fully digital triggering such as design, research, test, education, using the actual digitized data. This reduces trigger errors and allows our service and repair. oscilloscopes to trigger on the smallest signals, even at the full bandwidth. Pico USB-powered oscilloscopes are also Trigger levels and hysteresis can be set with high precision and resolution. -

Scope for Change Adding Variety to Test

www.electronicspecifier.com volume 1, 2016 Scope For Change Adding variety to test Strategy Shift Faster Data Test Challenge Open source – New logo heralds – AXIe digitisers – M2M/IoT need – Software platform new approach show the way new solutions for test applications TAKE YOUR DESIGN TO PRODUCTION • Over 650,000 products in stock • Unbeatable prices on volume orders • Local sales, technical and quoting teams closer to your business uk.farnell.com 04 CSP-BUYER-IBCport-210x297-UK.indd 1 02/10/2015 10:34 Contents Mobile World Congress 2016 10 06 Industry test and measurement heavyweights are preparing for a big week for any company connected to the Mobile world. Keysight Technologies, Rohde & Schwarz and Anritsu will all present developments for 5G testing alongside other wireless test products. New logo, new strategy 10 Tektronix is moving into 2016 with a new logo which heralds a change in its relationship with customers. Six brand principles have been introduced after extensive global research with customers and within the company. The company will now be looking at a collaborative approach based around customer applications Customised applications with AXIe products 12 A partnership between Keysight Technologies with a company called 12 Scientific Equipment has produced a 64 synchronous, multichannel data acquisition system composed of eight M9703A AXIe 12-bit high-speed digitisers/wideband digital receivers in a 14-slot chassis. Testing challenges for cellular M2M/IoT devices 16 Terms such as M2M (“machines talking to machines”) and IoT (“Internet of Things”) have started to invade our daily life, with short-range communication examples such as a watch communicating with a phone via Bluetooth or a Wi-Fi light bulb connected to a home router. -

Recreating Lab Measurements As RTL Stimulus

Torgeir Leithe Recreating lab measurements as RTL stimulus Master’s thesis in Electronic Systems Design Supervisor: Kjetil Svarstad June 2019 Master’s thesis Master’s NTNU Engineering Department of Electronic Systems Department of Electronic Faculty of Information Technology and Electrical Technology of Information Faculty Norwegian University of Science and Technology of Science University Norwegian Torgeir Leithe Recreating lab measurements as RTL stimulus Master’s thesis in Electronic Systems Design Supervisor: Kjetil Svarstad June 2019 Norwegian University of Science and Technology Faculty of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering Department of Electronic Systems Abstract Most of modern IC design verification is conducted as RTL simulations. However, the final verification steps must be done on physical silicon. If unexpected behavior is found at this stage, understanding the problem can be a challenge. The understanding of the problem is limited by all the internal signals and states in the DUT being hidden. Only the external signals can be probed. By recording all the stimulus applied to the IC, the conditions triggering the issue can be recreated in the RTL simulations. This enables a greater understanding of the inner workings of the IC at the time the issue occurs. This thesis investigates ways of assisting the designer in this process. By taking advantage of most stimulus applied to the DUT being part of a communication protocol, focus can be moved from the signals them self, to the information transmitted by the signals. Decoding the signals to a protocol level allows for reuse of existing testbenches. The information being presented at a protocol level also makes analysis of the problem simpler for the designer. -

Picoscope 3000 Quick Start Guide

PicoScope™ 3000 Quick start guide Pico Technology Ltd The Mill House Cambridge Street St. Neots Cambridgeshire PE19 1QB Tel: +44 (0) 1480 396 395 Fax: +44 (0) 1480 396 296 Email: [email protected] Web: www.picotech.com Included with your PicoScope… Your PicoScope 3000 package contains the following components: 1 PicoScope 320x series oscilloscope 1 USB cable 1 Pico Software CD 1 Power adapter (UK, EU or US – selected at time of ordering) 1 Installation guide 1 Quick start guide PicoScope 3000 Quick start… 1) Do not connect the PicoScope 3000 to the PC until software has been installed. 2) Insert CD which should automatically start Pico the installation application 3) Follow the links to install software 4) Follow the instructions on the screen to install PicoScope 5) Restart the PC 6) Click on “PicoScope” in the Windows Start menu to begin using PicoScope 3000. If you are using a scope probe and PicoScope, you should see a small 50Hz or 60Hz mains signal in the oscilloscope window when you touch the scope probe tip with your finger. Connector diagram Ch A) Input channel 1 Ch B) Input channel 2 1) USB port connector 2) 12Vdc 500mA power input 3) External trigger / Signal generator 4) LED. When lit, indicates the PicoScope 3000 series oscilloscope is sampling data PicoScope 3000 overview Oscilloscopes in the new PicoScope 3000 series all feature a high-speed USB 2.0 interface, together with impressive sampling rates, high bandwidths and a large buffer memory. PicoScope oscilloscopes simply connect to the USB port on any standard Windows based PC, making full use of the PCs' processing capabilities, large screens and familiar graphical user interfaces. -

Mobile Data-Logger for Ultra-Low Current and Power Measurements

Institut für Technische Informatik und Kommunikationsnetze Department of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering Spring Semester 2016 RocketLogger: Mobile Data-Logger for Ultra-Low Current and Power Measurements Semester Thesis, SA-2016-40 Matthias Leubin, Stefan Lippuner [email protected], [email protected] June 2016 Supervisors: Lukas Sigrist, [email protected] Andres Gomez, [email protected] Roman Lim, [email protected] Professor: Prof. Dr. L. Thiele, [email protected] Abstract With the appearance of wearable devices and the Internet of Things (IoT), energy harvesting nodes are becoming more and more important. These small standalone sensors and actuators, which harvest very lim- ited amounts of energy from their environment, are driving researchers into the development of ultra-low power devices. To evaluate new de- signs, very accurate and fast measurement systems are required, which are able to capture the rapidly changing currents. On the other hand, the necessity of real-world experiments creates a demand for compact and portable equipment. In this thesis we present the RocketLogger, a measurement device, which combines both properties, mobility and accuracy. It is able to measure powers in the range of 100 pW up to 2.5 W within the same measure- ment, while not being bigger than a human hand. The custom analog front-end allows the logging of power on several channels with sampling rates of up to 64 kSPS. In addition, it guarantees high precision over a dynamic range of 165 dB and has a seamless auto-ranging capability. The software handles the acquisition and logging of up to 13 Mbit/s of sensor data. -

Picoscope 4824 Data Sheet

PicoScope® 4824 High-precision PC oscilloscope 8 channels 20 MHz bandwidth 12 bit vertical resolution 256 MS buffer memory 80 MS/s sampling rate 1% DC accuracy ±10 mV to ±50 V input ranges 10 000 segment waveform buffer 80 MS/s AWG update rate 14 bit resolution AWG Low-cost and portable SuperSpeed USB 3.0 interface Split-screen waveform viewing Low sine and pulse distortion Advanced digital triggers Serial bus decoding Applications Power supply start sequencing 7 channel audio systems Multi-sensor systems Multi-phase drives and controls General-purpose and precision testing Complex embedded system development 5 year warranty www.picotech.com 8 channel oscilloscope With 8 high-resolution analog channels you can easily view audio, ultrasonic, vibration and power waveforms, analyze timing of complex systems, and perform a wide range of precision measurement tasks on multiple inputs at the same time. Although the scope has the same small footprint as Pico’s existing 2- and 4-channel models, the BNC connectors with 20 mm spacing still accept all common probes and accessories. Despite its compact size, there is no compromise on performance. With a high vertical resolution of 12 bits, 20 MHz bandwidth, 256 MS buffer memory, and a fast sampling rate of 80 MS/s, the PicoScope 4824 has the power and functionality to deliver accurate results. It also features deep memory to analyze multiple serial buses such as UART, I2C, SPI, CAN and LIN plus control and driver signals. Arbitrary waveform and function generators In addition, the PicoScope 4824 has a built-in low-distortion, 80 MS/s, 14 bit arbitrary waveform generator (AWG), which can be used to emulate missing sensor signals during product development, or to stress-test a design over the full intended operating range. -

Picoscope 6 PC Oscilloscope Software

SUPERSEDED PicoScope 6 PC Oscilloscope Software User's Guide psw.en r33 Copyright © 2007-2014 Pico Technology Ltd. All rights reserved. SUPERSEDED SUPERSEDED SUPERSEDED SUPERSEDED PicoScope 6 User's Guide I Table of Contents 1 Welcome ....................................................................................................................................1 2 PicoScope 6. ...................................................................................................................................2overview 3 Introduction....................................................................................................................................3 1 Legal statement ........................................................................................................................................3 2 Upgrades ........................................................................................................................................3 3 Trade marks ........................................................................................................................................4 4 Contact information ........................................................................................................................................4 5 How to use this manual........................................................................................................................................4 6 System requirements........................................................................................................................................5 -

Sigrok: Using Logic to Debug Logic

Sigrok: Using Logic to Debug Logic Matt Ranostay Intel Open Source Technology Center [email protected] sigrok Overview • Provides a simple Open Source solution for mostly proprietary and some Open Source Hardware digital logic devices • Common framework which includes output format, device metadata, and H/W interfacing sigrok Project • Blanket project with various libraries, backends, protocol decoders, third-party firmware, and graphical frontends • Aims to make a common framework for a various of logic analyzers, oscilloscopes, and other analog/digital debugging devices Meet The Family • libsigrok – Heart and brains behind the device communication, functionality, and control • libsigrokdecode – Python3 interfacing lib in C + protocol decoders • sigrok-cli – Command line backend for sigrok • sigrok-util – Various useful scripts + utilities • sigrok-dumps – Collections of various captures • fx2lafw – OSS Firmware for Cypress FX2 LAs • PulseView – sigrok QT GUI frontend sigrok Components sigrok-cli H/W Interface libsigrok PulseView libsigrokdecode Plugins + Bindings Examples of Supported Devices • Logic Analyzers ▫ Open Logic Sniffer ▫ Saleae Logic/Logic 16 • Oscilloscope ▫ Rigol DS1052E • Mixed-Mode Devices • Digital Multimeter • Analog devices like thermometers, hygrometers, light meters, etc • Full support list available on sigrok wiki Supported Devices sigrok output format • Device agnostic and interchangeable • Simple hexdump to process • Compressed with zip algorithm ▫ Due to most samples being repeats it isn’t rare to see -

Picoscope 6 User's Guide I

PicoScope® 6 PC Oscilloscope Software User's Guide psw.en r50 PicoScope 6 User's Guide I Table of Contents 1 Welcome ............................................................................................................................. 1 2 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 1 Legal statement ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2 Updates ................................................................................................................................................... 4 3 Trademarks ............................................................................................................................................ 4 4 System requirements ............................................................................................................................. 5 3 Using PicoScope for the first time .................................................................................... 6 4 PicoScope and oscilloscope primer ................................................................................. 7 1 Oscilloscope basics ............................................................................................................................... 7 2 PC Oscilloscope basics ......................................................................................................................... 8 3 PicoScope