Minimizing Wages & Worker Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARCH 19 Layout 1

Focus at MHA on Still no room Congresswoman Clark respect, integrity, sees value of loan repay compassion at the inn VIEWPOINTS: DITORIAL PROVIDER PROFILE: E : PAGE 5 PAGE 4 PAGE 3 Vol. 40 - No. 3 The Newspaper of the Providers’ Council March 2019 Roundtable Federal, state discussion policy work gone to pot in spotlight he Providers’ Council and Massa- Organizations need to chusetts Nonprofit Network sent Ta joint letter to Congressman update policies, train staff Richard Neal (D-Mass.), Chair of the he legalization of marijuana usage Joint Committee on Taxation, urging in Massachusetts – for both medic- the immediate repeal of the new income Tinal and recreational purposes – is tax on expenses incurred by nonprofits creating new challenges and questions for providing employee transportation for human services providers about use benefits, such as parking and transit by both employees and clients. passes. Together, the Council and MNN Nearly 40 people representing 27 represent nearly 1,000 nonprofit or- Providers’ Council member organizations ganizations throughout Massachusetts. attended an HR Roundtable on Mari- The new tax – officially Internal Rev- juana Legalization Policies and Proce- enue Code Section 512(a)(7) – is a part dures hosted by the Council on Feb. 20 of the sweeping tax code reform passed in Needham to discuss their challenges in 2017 and the first payments will be and learn about best practices. due in a matter of weeks. It imposes a A panel – including attorneys Jeffrey 21 percent tax on nonprofits offering Hirsch and Peter Moser from the law firm transportation-related benefits to em- Hirsch Roberts Weinstein LLP; Senior ployees. -

We're Here for You!

wvv we speak sabatino • español Please call us! • portuguêse insurance agency • italiano We’re here for You! Rocco Longo all types of insurance! • auto • home • rental • flood • business • commercial 617-387-7466 | 564 Broadway, Everett | sabatino-ins.com Everett IndependentPublished by the Independent Newspaper Co. Wednesday, August 12, 2020 Everett tagged School Committee ‘high-risk’ community approves phased By Seth Daniel re-opening plan Everett health officials said they are watching By Seth Daniel school officials, City lead- closely as cases are going ers and parents. It is, she up slightly over the past The Everett School Com- said, a very unique plan as few weeks, with an average mittee voted 7-0 during well. of about six cases per day an Emergency Meeting on “Our approach is differ- after having it down as low Aug. 6 to approve a school ent from that being taken as zero cases around July 4. re-opening plan that starts by other districts,” she said. On Tuesday afternoon, the year mostly remote, “It is not likely something Gov. Charlie Baker did but will offer e-Learning you have heard mentioned designate Everett, Chel- Centers for the most needy in any of the numbers of sea, Revere and Lynn as students and to families that media reports that have put higher-risk communities in need child supervision or forth every probable sce- BlueBikes announced a new, free pass program for workers in grocery stores, restaurants, don’t have reliable internet nario schools might enact the state compared to else- pharmacies and retail. where, with rates at greater access. -

An Act to Promote Public Safety and Better Outcomes for Young Adults – S.825/H.3420

An Act to Promote Public Safety and Better Outcomes for Young Adults – S.825/H.3420 Lead Sponsors MASSACHUSETTS CURRENTLY SPENDS THE MOST MONEY ON Sen. Joseph Boncore (Winthrop) YOUNG ADULTS IN THE JUSTICE SYSTEM AND GETS THE Rep. James O'Day (West Boylston) Rep. Kay Khan (Newton) WORST OUTCOMES Co-Sponsors Shifting 18- to 20-year-olds into the juvenile system, where Rep. Ruth Balser (Newton) they must attend school and participate in rehabilitative Rep. Christine Barber (Somerville) programming, would lower recidivism. The young adult Sen. Michael Brady (Brockton) brain is still developing making them highly amenable to Rep. Mike Connolly (Cambridge) rehabilitation. This development is influenced – Sen. Brendan Crighton (Lynn) positively or negatively – by their environment. Rep. Daniel Cullinane (Dorchester) Sen. Julian Cyr (Truro) An overly punitive approach can actually cause more Rep. Marjorie Decker (Cambridge) Rep. Marcos Devers (Lawrence) offending: Most young people "age out" of offending by their Sen. Sal DiDomenico (Everett) mid-twenties, particularly with developmentally appropriate Rep. Daniel Donahue (Worcester) interventions. Exposure to toxic environments, like adult jails Rep. Carolyn Dykema (Holliston) and prisons, entrenches young people in problematic Sen. James Eldridge (Acton) behaviors, increasing probability of recidivism. Rep. Tricia Farley-Bouvier (Pittsfield) Sen. Cindy Friedman (Arlington) Recidivism among young people incarcerated in the adult Rep. Sean Garballey (Arlington) corrections is more than double similar youth released Rep. Carlos González (Springfield) from department of youth services commitment Rep. Tami Gouveia (Acton) Teens and young adults incarcerated in Massachusetts’ adult Rep. Jim Hawkins (Attleboro) correctional facilities have a 55% re-conviction rate, Rep. Stephan Hay (Fitchburg) compared to a similar profile of teens whose re-conviction Rep. -

Name Office Sought District

The candidates listed below have taken the Commonwealth Environmental Pledge. Name Office Sought District Gerly Adrien State Representative 28th Middlesex Representative Ruth B Balser State Representative 12th Middlesex Bryan P Barash Newton City Council Ward 2 Representative Christine P Barber State Representative 34th Middlesex Alex Bezanson State Representative 7th Plymouth 2nd Suffolk and Senator Will Brownsberger State Senate Middlesex Suezanne Patrice Bruce State Representative 9th Suffolk Michelle Ciccolo State Representative 15th Middlesex Matthew Cohen State Representative 15th Middlesex Hampshire, Franklin Jo Comerford State Senate and Worcester Representative Dan Cullinane State Representative 12th Suffolk Paul Cusack State Representative 2nd Barnstable Senator Julian Cyr State Senate Cape and Islands Representative Michael Day State Representative 31st Middlesex Representative Diana DiZoglio State Senate 1st Essex Christina Eckert State Representative 2nd Essex Representative Lori A. Ehrlich State Representative 8th Essex Middlesex and Senator James Eldridge State Senate Worcester Senator Paul Feeney State Senate Bristol and Norfolk Barnstable, Dukes and Representative Dylan Fernandes State Representative Nantucket 2nd Essex and Barry Finegold State Senate Middlesex Senator Cindy F. Friedman State Senate 4th Middlesex Representative Sean Garballey State Representative 23rd Middlesex Representative Carmine Lawrence Gentile State Representative 13th Middlesex 15 Court Square, Suite 1000, Boston, MA 02108 • (617) 742-0474 • www.elmaction.org Allison Gustavson State Representative 4th Essex Representative Solomon Goldstein-Rose State Representative 3rd Hampshire Tami Gouveia State Representative 14th Middlesex Representative Jim Hawkins State Representative 2nd Bristol Sabrina Heisey State Representative 36th Middlesex Sarah G. Hewins State Representative 2nd Plymouth Representative Natalie Higgins State Representative 4th Worcester Kevin Higgins State Representative 7th Plymouth John Hine State Representative 2nd Hampshire Senator Patricia D. -

HOUSE ...No. 2827

HOUSE DOCKET, NO. 1932 FILED ON: 1/17/2019 HOUSE . No. 2827 The Commonwealth of Massachusetts _________________ PRESENTED BY: Edward F. Coppinger _________________ To the Honorable Senate and House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in General Court assembled: The undersigned legislators and/or citizens respectfully petition for the adoption of the accompanying bill: An Act relative to transparency in private utility construction contracts. _______________ PETITION OF: NAME: DISTRICT/ADDRESS: Edward F. Coppinger 10th Suffolk Louis L. Kafka 8th Norfolk Steven Ultrino 33rd Middlesex Frank A. Moran 17th Essex Timothy R. Whelan 1st Barnstable Angelo J. Puppolo, Jr. 12th Hampden Brian W. Murray 10th Worcester Richard M. Haggerty 30th Middlesex Daniel Cahill 10th Essex José F. Tosado 9th Hampden David Paul Linsky 5th Middlesex Tommy Vitolo 15th Norfolk Joseph W. McGonagle, Jr. 28th Middlesex Tackey Chan 2nd Norfolk Mike Connolly 26th Middlesex Daniel J. Ryan 2nd Suffolk James B. Eldridge Middlesex and Worcester Stephan Hay 3rd Worcester 1 of 5 David M. Rogers 24th Middlesex Alice Hanlon Peisch 14th Norfolk Christopher Hendricks 11th Bristol Angelo M. Scaccia 14th Suffolk Smitty Pignatelli 4th Berkshire Thomas P. Walsh 12th Essex Daniel M. Donahue 16th Worcester Rady Mom 18th Middlesex Mathew J. Muratore 1st Plymouth Danielle W. Gregoire 4th Middlesex Carmine Lawrence Gentile 13th Middlesex Marc T. Lombardo 22nd Middlesex David F. DeCoste 5th Plymouth Bruce E. Tarr First Essex and Middlesex Bud L. Williams 11th Hampden Natalie M. Higgins 4th Worcester Mary S. Keefe 15th Worcester Joseph F. Wagner 8th Hampden Denise C. Garlick 13th Norfolk Antonio F. D. Cabral 13th Bristol Kimberly N. -

100% Renewable Energy Agenda 2019-2020 Legislative Session

! The 100% Renewable Energy Agenda 2019-2020 Legislative Session The 100% Renewable Energy Act Repower Massachusetts with 100 percent renewable electricity by 2035 and 100 percent renewable energy economy-wide (including heating and transportation) by 2045. • HD 3092: Rep. Marjorie Decker, Rep. Sean Garballey An Act re-powering Massachusetts with 100 percent renewable energy • SD 1625: Sen. Jamie Eldridge An Act transitioning Massachusetts to 100 per cent renewable energy Renewable electricity Community Empowerment An Act for community empowerment: Allow 25% solar power by 2030 cities and towns to support renewable en- An Act relative to solar power and the green ergy projects, like solar and offshore wind, economy: Eliminate caps on solar net me- by leveraging the buying power of their res- tering and increase the renewable portfolio idents. standard by 3 percent per year. • HD 3717: Rep. Dylan Fernandes • HD 2529: Rep. Paul Mark • SD 2098: Sen. Julian Cyr • SD 1376: Sen. Jamie Eldridge Clean Energy Future Act Solar roofs for new homes and businesses An Act to secure a clean energy future: In- An Act increasing solar rooftop energy: Re- crease solar, offshore wind, energy storage, quire solar panels to be installed on new and electric vehicles to get closer to zero residential and commercial buildings. carbon emissions by 2050. • HD 2890: Rep. Mike Connolly, Rep. Jack • HD 1248: Rep. Ruth Balser Lewis • SD 757: Sen. Marc Pacheco • SD 1532: Sen. Jamie Eldridge Contact: Ben Hellerstein, [email protected], 617-747-4368 Efficient buildings and appliances Clean transportation Net zero building code All-electric buses by 2035 An Act to establish a net zero stretch energy An Act transitioning Massachusetts to electric code: Allow cities and towns to adopt a buses: Require all transit buses and school stronger building code for highly efficient, buses to be clean electric vehicles by 2035. -

SNAP Gap Cosponsors - H.1173/S.678 91 Representatives & 28 Senators

SNAP Gap Cosponsors - H.1173/S.678 91 Representatives & 28 Senators Rep. Jay Livingstone (Sponsor) Representative Daniel Cahill Representative Jack Patrick Lewis Senator Sal DiDomenico (Sponsor) Representative Peter Capano Representative David Linsky Senator Michael Barrett Representative Daniel Carey Representative Adrian Madaro Senator Joseph Boncore Representative Gerard Cassidy Representative John Mahoney Senator William Brownsberger Representative Michelle Ciccolo Representative Elizabeth Malia Senator Harriette Chandler Representative Mike Connolly Representative Paul Mark Senator Sonia Chang-Diaz Representative Edward Coppinger Representative Joseph McGonagle Senator Jo Comerford Representative Daniel Cullinane Representative Paul McMurtry Senator Nick Collins Representative Michael Day Representative Christina Minicucci Senator Brendan Crighton Representative Marjorie Decker Representative Liz Miranda Senator Julian Cyr Representative David DeCoste Representative Rady Mom Senator Diana DiZoglio Representative Mindy Domb Representative Frank Moran Senator James Eldridge Representative Daniel Donahue Representative Brian Murray Senator Ryan Fattman Representative Michelle DuBois Representative Harold Naughton Senator Paul Feeney Representative Carolyn Dykema Representative Tram Nguyen Senator Cindy Friedman Representative Lori Ehrlich Representative James O'Day Senator Anne Gobi Representative Nika Elugardo Representative Alice Peisch Senator Adam Hinds Representative Tricia Farley-Bouvier Representative Smitty Pignatelli Senator -

METCO Legislators 2020

Phone (617) Address for newly District Senator/Representative First Name Last Name 722- Room # Email elected legislators Boston Representative Aaron Michlewitz 2220 Room 254 [email protected] Boston Representative Adrian Madaro 2263 Room 473-B [email protected] Natick, Weston, Wellesley Representative Alice Hanlon Peisch 2070 Room 473-G [email protected] East Longmeadow, Springfield, Wilbraham Representative Angelo Puppolo 2006 Room 122 [email protected] Boston Representative Rob Consalvo [email protected] NEW MEMBER Needham, Wellesley, Natick, Wayland Senator Becca Rausch 1555 Room 419 [email protected] Reading, North Reading, Lynnfield, Middleton Representative Bradley H. Jones Jr. 2100 Room 124 [email protected] Lynn, Marblehead, Nahant, Saugus, Swampscott, and Melrose Senator Adam Gomez [email protected] NEW MEMBER Longmeadow, Hampden, Monson Representative Brian Ashe 2430 Room 236 [email protected] Springfield Representative Bud Williams 2140 Room 22 [email protected] Springfield Representative Carlos Gonzales 2080 Room 26 [email protected] Sudbury and Wayland, Representative Carmine Gentile 2810 Room 167 [email protected] Boston Representative Chynah Tyler 2130 Room 130 [email protected] Woburn, Arlington, Lexington, Billerica, Burlington, Lexington Senator Cindy Friedman 1432 Room 413-D [email protected] Boston Senator Nick Collins 1150 Room 410 [email protected] Newton, Brookline, Wellesley Senator Cynthia Stone Creem 1639 Room 312-A [email protected] Boston, Milton Representative Dan Cullinane 2020 Room 527-A [email protected] Boston, Milton Representative Fluker Oakley Brandy [email protected] Boston, Chelsea Representative Daniel Ryan 2060 Room 33 [email protected] Boston Representative Daniel J. -

October 30, 2020 Secretary Stephanie Pollack Jeffrey Mcewen

October 30, 2020 Secretary Stephanie Pollack Jeffrey McEwen Massachusetts Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration 10 Park Plaza, Suite 4160 55 Broadway, 10th Floor Boston, MA 02116 Cambridge, MA 02142 [email protected] [email protected] Dear Secretary Pollack and Administrator McEwen, Over the past six years all of us have welcomed the opportunity to comment on MassDOT’s designs to the I-90 Allston Interchange/Allston Multimodal Project. We also understand this project is a transformative, once-in-a-generation project. As elected officials representing communities directly abutting this project and elected officials whose constituents will be severely affected by this project, we are all in agreement that of the three proposals that are under consideration of NEPA submission the Modified All At-Grade Proposal is the only plan that should move forward in this process. Our constituents span from Boston to Worcester and beyond, and the Modified All At-Grade Proposal is the least disruptive to commuter rail riders and allows for the most lanes to be in use on the Mass Pike during construction. For commuter rail riders, the Modified All At-Grade Proposal lays the foundation for a transformative transportation network expanding transit from MetroWest communities. Likewise, for drivers, the Modified All At-Grade Proposal provides the most safe, straight, and flat highway. We feel that at this critical moment for the future of this project, it is important for us to express our utmost desire for MassDOT to pick the Modified All At-Grade Proposal as the preferred alternative. Despite some competing interests from various large institutions and economic sectors, the Modified All At-Grade Proposal has garnered the most widespread support because of its transformative impacts for generations to come. -

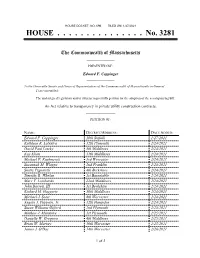

HOUSE ...No. 3281

HOUSE DOCKET, NO. 696 FILED ON: 1/27/2021 HOUSE . No. 3281 The Commonwealth of Massachusetts _________________ PRESENTED BY: Edward F. Coppinger _________________ To the Honorable Senate and House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in General Court assembled: The undersigned legislators and/or citizens respectfully petition for the adoption of the accompanying bill: An Act relative to transparency in private utility construction contracts. _______________ PETITION OF: NAME: DISTRICT/ADDRESS: DATE ADDED: Edward F. Coppinger 10th Suffolk 1/27/2021 Kathleen R. LaNatra 12th Plymouth 2/24/2021 David Paul Linsky 5th Middlesex 2/24/2021 Kay Khan 11th Middlesex 2/24/2021 Michael P. Kushmerek 3rd Worcester 2/24/2021 Susannah M. Whipps 2nd Franklin 2/24/2021 Smitty Pignatelli 4th Berkshire 2/24/2021 Timothy R. Whelan 1st Barnstable 2/24/2021 Marc T. Lombardo 22nd Middlesex 2/24/2021 John Barrett, III 1st Berkshire 2/24/2021 Richard M. Haggerty 30th Middlesex 2/24/2021 Michael J. Soter 8th Worcester 2/24/2021 Angelo J. Puppolo, Jr. 12th Hampden 2/24/2021 Susan Williams Gifford 2nd Plymouth 2/25/2021 Mathew J. Muratore 1st Plymouth 2/25/2021 Danielle W. Gregoire 4th Middlesex 2/25/2021 Brian W. Murray 10th Worcester 2/25/2021 James J. O'Day 14th Worcester 2/26/2021 1 of 2 Peter Capano 11th Essex 2/26/2021 Lindsay N. Sabadosa 1st Hampshire 2/26/2021 Christopher Hendricks 11th Bristol 2/26/2021 Jessica Ann Giannino 16th Suffolk 2/26/2021 Diana DiZoglio First Essex 2/26/2021 Michael S. Day 31st Middlesex 2/26/2021 James M. -

January 28, 2021 the Honorable Charles D. Baker Office of The

January 28, 2021 The Honorable Charles D. Baker Office of the Governor Massachusetts State House Boston, MA 02133 Dear Governor Baker: We write to you to express our concern regarding the current process available to the public to sign up for COVID-19 vaccines. Our constituencies have called on us for assistance in navigating the pathway laid out by your Administration. The system in use, while made to be expedient and accessible, has created barriers for our aging population, those who have limited access to technology, and those who struggle to use it. Inadvertently, restricting the sign up process to a digital format puts our senior population at risk. In searching for the official online tool, the query also provides results not affiliated with the Commonwealth. This makes residents vulnerable to scams, and exposes them to undue online risks. Collectively, we implore the Administration to create a user friendly 1-800 number which would allow Massachusetts residents to access the sign up process more easily. Additionally, we request that the Administration create a centralized system, under the COVID-19 Task Force, that would allow for a more accessible sign-up process for those who can utilize the online tools. Currently, residents must choose a location, and then follow one of many links to separate entities to book appointments. We are appreciative for the steps that the Administration has taken, and are grateful for your consideration. Please contact our offices should you have questions, concerns, or wish to discuss this further. Sincerely, Anne M. Gobi Adam Gomez State Senator State Senator Worcester, Hampden, Hampshire Middlesex District Hampden District Eric P. -

Eastie Man Indicted on Child Sexual Assault, Child Pornography Charges

Jeffrey Bowen 781-201-9488 12 new construction luxury condos for [email protected] sale in Chelsea located at 87 Parker St. chelsearealestate.com for details BOOK YOUR POST IT Call Your Advertising Rep T IMES -F REE P RESS (781)485-0588 East BostonWednesday, March 27, 2019 Tramelli named as new East Boston Liaison By John Lynds couldn’t be more excited for her to become the East Bos- Last week Mayor Martin ton liaison,” said Walsh. “East Walsh announced the appoint- Boston is a neighborhood full ment of Lina Tramelli as the of tradition, growth and diver- East Boston Neighborhood sity and I know she will con- Liaison within the Mayor’s tinue to be an advocate for the Civic Engagement Cabinet. residents and businesses in Tramelli will replace Jesús East Boston.” García-Mota who will now As the East Boston liaison, become Mayor Walsh’s City- Tramelli will serve as the pri- wide liaison to the Latino mary contact for constituents community. and businesses looking to Tramelli will officially be- connect with the Mayor’s Of- gin serving as Eastie’s liaison fice, and will facilitate the de- on April 8. livery of services in collabo- “Lina has a fantastic back- Lina Tramelli announced as ground in public service and I See TRAMELLI Page 2 new East Boston Liaison. Eastie man indicted on child sexual assault, child pornography charges By John Lynds semination of matter harmful of the worst crimes against to a minor; three counts of children,” said District Attor- An East Boston man was posing a child in a state of nu- ney Rollins.