Hillis 1 Demystifying Dutilleux and Lutosławski: a Language Representative of Our Modern Time Amy Hillis Department of Performa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polish Music Since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More Information

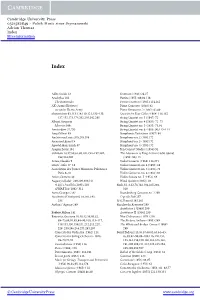

Cambridge University Press 0521582849 - Polish Music since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More information Index Adler,Guido 12 Overture (1943) 26,27 Aeschylus 183 Partita (1955) 69,94,116 The Eumenides Pensieri notturni (1961) 114,162 AK (Armia Krajowa) Piano Concerto (1949) 62 see under Home Army Piano Sonata no. 2 (1952) 62,69 aleatoricism 93,113,114,119,121,132–133, Quartet for Four Cellos (1964) 116,162 137,152,173,176,202,205,242,295 String Quartet no. 3 (1947) 72 Allegri,Gregorio String Quartet no. 4 (1951) 72–73 Miserere 306 String Quartet no. 5 (1955) 73,94 Amsterdam 32,293 String Quartet no. 6 (1960) 90,113–114 Amy,Gilbert 89 Symphonic Variations (1957) 94 Andriessen,Louis 205,265,308 Symphony no. 2 (1951) 72 Ansermet,Ernest 9 Symphony no. 3 (1952) 72 Apostel,Hans Erich 87 Symphony no. 4 (1953) 72 Aragon,Louis 184 Ten Concert Studies (1956) 94 archaism 10,57,60,61,68,191,194–197,294, The Adventure of King Arthur (radio opera) 299,304,305 (1959) 90,113 Arrau,Claudio 9 Viola Concerto (1968) 116,271 artists’ cafés 17–18 Violin Concerto no. 4 (1951) 69 Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais a` Violin Concerto no. 5 (1954) 72 Paris 9–10 Violin Concerto no. 6 (1957) 94 Attlee,Clement 40 Violin Sonata no. 5 (1951) 69 Augustyn,Rafal 289,290,300,311 Wind Quintet (1932) 10 A Life’s Parallels (1983) 293 Bach,J.S. 8,32,78,182,194,265,294, SPHAE.RA (1992) 311 319 Auric,Georges 7,87 Brandenburg Concerto no. -

Concert Programdownload Pdf(349

The University at Buffalo Department of Music and The Robert & Carol Morris Center for 21st Century Music present Stockhausen's Mantra For Two Pianos Eric Huebner and Steven Beck, pianos Sound and electronic interface design: Ryan MacEvoy McCullough Sound projection: Chris Jacobs and Ryan MacEvoy McCullough Saturday, October 14, 2017 7:30pm Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall PROGRAM Mantra (1970) Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928 – 2007) Program Note by Katherine Chi To say it as simply as possible, Mantra, as it stands, is a miniature of the way a galaxy is composed. When I was composing the work, I had no accessory feelings or thoughts; I knew only that I had to fulfill the mantra. And it demanded itself, it just started blossoming. As it was being constructed through me, I somehow felt that it must be a very true picture of the way the cosmos is constructed, I’ve never worked on a piece before in which I was so sure that every note I was putting down was right. And this was due to the integral systemization - the combination of the scalar idea with the idea of deriving everything from the One. It shines very strongly. - Karlheinz Stockhausen Mantra is a seminal piece of the twentieth century, a pivotal work both in the context of Stockhausen’s compositional development and a tour de force contribution to the canon of music for two pianos. It was written in 1970 in two stages: the formal skeleton was conceived in Osaka, Japan (May 1 – June 20, 1970) and the remaining work was completed in Kürten, Germany (July 10 – August 18, 1970). -

Leo Kraft's Three Fantasies for Flute and Piano: a Performer's Analysis

CHERNOV, KONSTANTZA, D.M.A. Leo Kraft's Three Fantasies for Flute and Piano: A Performer's Analysis. (2010) Directed by Dr. James Douglass. 111 pp. The Doctoral Performance and Research submitted by Konstantza Chernov, under the direction of Dr. James Douglass at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNCG), in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts, consists of the following: I. Chamber Recital, Sunday, April 27, 2008, UNCG: Trio for Piano, Clarinet and Violoncello in Bb Major, op. 11 (Ludwig van Beethoven) Sonatine for Flute and Piano (Henri Dutilleux) Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Major (César Franck) II. Chamber Recital, Monday, November 17, 2008, UNCG: Sonata for Violin and Piano in g minor (Claude Debussy) El Poema de una Sanluqueña, op. 28 (Joaquin Turina) Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Major, op. 13 (Gabriel Fauré) III. Chamber Recital, Tuesday, April 27, 2010, UNCG: Sonata for Two Pianos in D Major, K. 448 (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart) The Planets, op. 32: Uranus, The Magician (Gustav Holst) The Planets, op. 32: Neptune, The Mystic (Gustav Holst) Fantasie-tableaux (Suite #1), op. 5 (Sergei Rachmaninoff) IV. Lecture-Recital, Thursday, October 28, 2010, UNCG: Fantasy for Flute and Piano (Leo Kraft) Second Fantasy for Flute and Piano (Leo Kraft) Third Fantasy for Flute and Piano (Leo Kraft) V. Document: Leo Kraft's Three Fantasies for Flute and Piano: A Performer's Analysis. (2010) 111 pp. This document is a performer's analysis of Leo Kraft's Fantasy for Flute and Piano (1963), Second Fantasy for Flute and Piano (1997), and Third Fantasy for Flute and Piano (2007). -

CCMA Coleman Competition (1947-2015)

THE COLEMAN COMPETITION The Coleman Board of Directors on April 8, 1946 approved a Los Angeles City College. Three winning groups performed at motion from the executive committee that Coleman should launch the Winners Concert. Alice Coleman Batchelder served as one of a contest for young ensemble players “for the purpose of fostering the judges of the inaugural competition, and wrote in the program: interest in chamber music playing among the young musicians of “The results of our first chamber music Southern California.” Mrs. William Arthur Clark, the chair of the competition have so far exceeded our most inaugural competition, noted that “So far as we are aware, this is sanguine plans that there seems little doubt the first effort that has been made in this country to stimulate, that we will make it an annual event each through public competition, small ensemble chamber music season. When we think that over fifty performance by young people.” players participated in the competition, that Notices for the First Annual Chamber Music Competition went out the groups to which they belonged came to local newspapers in October, announcing that it would be held from widely scattered areas of Southern in Culbertson Hall on the Caltech campus on April 19, 1947. A California and that each ensemble Winners Concert would take place on May 11 at the Pasadena participating gave untold hours to rehearsal Playhouse as part of Pasadena’s Twelfth Annual Spring Music we realize what a wonderful stimulus to Festival sponsored by the Civic Music Association, the Board of chamber music performance and interest it Education, and the Pasadena City Board of Directors. -

Krzysztof Penderecki Quatuor Molinari

KRZYSZTOF PENDERECKI Quatuors nos 1-3 | Unterbrochen gedanke Quatuor avec clarinette | Trio à cordes QUATUOR MOLINARI André Moisan CLARINETTE / CLARINET ACD2 2736 KRZYSZTOF PENDERECKI (1933-2020) 1 ❙ Quatuor à cordes no 1 / String Quartet No. 1 (1960) [5:57] Quatuor à cordes no 2 / String Quartet No. 2 (1968) 2 ❙ Lento molto - Vivace - Lento molto [9:09] QUATUOR MOLINARI 3 ❙ Der unterbrochene Gedanke (1988) [2:05] [ La pensée interrompue - The Broken Thought ] OLGA RANZENHOFER PREMIER VIOLON / FIRST VIOLIN ANTOINE BAREIL DEUXIÈME VIOLON DEPUIS 2018 / SECOND VIOLIN SINCE 2018 Trio à cordes / String Trio (1990)* DEUXIÈME VIOLON / SECOND VIOLIN 4 ❙ I. Allegro molto - Andante - Allegro molto - Allegretto - Allegro molto - Andante -Vivo [8:28] FRÉDÉRIC BEDNARZ pour cet enregistrement / for this recording 5 ❙ II. Vivace [5:15] FRÉDÉRIC LAMBERT ALTO / VIOLA VIOLONCELLE / CELLO Quatuor pour clarinette et trio à cordes / Quartet for clarinet and string trio (1993) PIERRE-ALAIN BOUVRETTE 6 ❙ I. Notturno : Adagio [3:16] ANDRÉ MOISAN CLARINETTE / CLARINET 7 ❙ II. Scherzo : Vivacissimo [2:22] 8 ❙ III. Serenade : Tempo di Valse [1:32] 9 ❙ IV. Abschied : Larghetto [7:36] 10 ❙ Quatuor à cordes no 3 / String Quartet No. 3 (2008) [16:41] Blätter eines nicht geschriebenen Tagebuches [ Pages d’un journal non écrit - “Leaves from an Unwritten Diary” ] * Frédéric Bednarz violon / violin ❙ QUATUOR NO 1 trémolos criants mettent un terme à toute cette frénésie. S’ensuit une section très douce, jouant sur la variation de la vitesse et de l’ambitus du vibrato sur de longues notes, qui est interrompue à Krzysztof Penderecki (1933-2020) fait une entrée remarquée comme compositeur sur la scène quelques reprises. -

A Global Sampling of Piano Music from 1978 to 2005: a Recording Project

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: A GLOBAL SAMPLING OF PIANO MUSIC FROM 1978 TO 2005 Annalee Whitehead, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2011 Dissertation directed by: Professor Bradford Gowen Piano Division, School of Music Pianists of the twenty-first century have a wealth of repertoire at their fingertips. They busily study music from the different periods Baroque, Classical, Romantic, and some of the twentieth century trying to understand the culture and performance practice of the time and the stylistic traits of each composer so they can communicate their music effectively. Unfortunately, this leaves little time to notice the composers who are writing music today. Whether this neglect proceeds from lack of time or lack of curiosity, I feel we should be connected to music that was written in our own lifetime, when we already understand the culture and have knowledge of the different styles that preceded us. Therefore, in an attempt to promote today’s composers, I have selected piano music written during my lifetime, to show that contemporary music is effective and worthwhile and deserves as much attention as the music that preceded it. This dissertation showcases piano music composed from 1978 to 2005. A point of departure in selecting the pieces for this recording project is to represent the major genres in the piano repertoire in order to show a variety of styles, moods, lengths, and difficulties. Therefore, from these recordings, there is enough variety to successfully program a complete contemporary recital from the selected works, and there is enough variety to meet the demands of pianists with different skill levels and recital programming needs. -

Escola De Música Programa De Pós-Graduação Em Música

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA ESCOLA DE MÚSICA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM MÚSICA PEDRO AUGUSTO SILVA DIAS Centricidade e Forma em Três Movimentos Para Clarinete e Orquestra Salvador 2009 Pedro Augusto Silva Dias Centricidade e Forma em Três Movimentos Para Clarinete e Orquestra Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-graduação em Música, Escola de Música, Universidade Federal da Bahia, como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Música. Área de concentração: Composição Orientador: Prof. Dr. Paulo Costa Lima Salvador 2009 ii © Copyright by Pedro Augusto Silva Dias Outubro 2009 iii TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO Pedro Augusto Silva Dias Centricidade e Forma em Três Movimentos para Clarinete e Orquestra Dissertação aprovada como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Música, Universidade Federal da Bahia, pela seguinte banca examinadora: Prof. Dr. Paulo Costa Lima – orientador Doutor em Educação, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Doutor em Artes pela Universidade de São Paulo / UFBA Prof. Dr. Wellington Gomes Doutor em Composição, Universidade Federal da Bahia / UFBA Prof. Dr. Antônio Borges-Cunha Doutor em Música, Universidade da Califórnia (EUA) / UFRGS iv Agradecimentos / Dedicatória A meus pais, por tudo. A Tina, pela compreensão, apoio e dedicação. A Roninho, pela inestimável amizade. A meus orientadores Pedro Kroger e Paulo Lima, pela guiança e estima. A Maria, Nati, Joaquim e Vicente, pelo amor. v Resumo Este trabalho procura fornecer uma visão geral sobre centricidade – termo usado para designar estratégias de priorização de classes de notas que escapam tanto às técnicas de análise tonal tradicional como às técnicas de análise ligadas ao serialismo – ilustrando diversos conceitos, processos, mecanismos e materiais ligados a esse fenômeno, e envolvendo autores estilisticamente tão diversos quanto Richard Strauss, Bartók, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Hindemith e Thomas Adès. -

Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra, IBA Leon Botstein, Musical Director & Conductor

Cal Performances Presents Sunday, October 26, 2008, 7pm Zellerbach Hall Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra, IBA Leon Botstein, Musical Director & Conductor with Robert McDuffie,violin PROGRAM Ernst Toch (1887–1964) Big Ben, Variation Fantasy on the Westminster Chimes, Op. 62 (1934) Miklós Rózsa (1907–1995) Violin Concerto, Op. 24 (1953–1954) Robert McDuffie, violin Allegro Lento cantabile Allegro vivace INTERMISSION Aaron Copland (1900–1990) Symphony No. 3 (1944–1946) Molto moderato Allegro molto Andantino quasi allegretto Molto deliberator — Allegro risoluto Program subject to change. The 2008 U.S. tour of the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra is made possible by Stewart and Lynda Resnick, El Al Airlines and Friends of the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra. Cal Performances’ 2008–2009 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo Bank. CAL PERFORMANCES 19 Orchestra Roster Orchestra Roster Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra, IBA Leon Botstein, Musical Director & Conductor Bass Clarinet Tuba Sigal Hechtlinger Guy Hardan, Principal Violin I Cello Bassoon Timpani Jenny Hunigen, Concertmaster Irit Assayas, Principal Richard Paley, Principal Yoav Lifshitz, Principal Ayuni Anna Paul, Concertmaster Ina-Esther Joost Ben Sassoon, Principal Alexander Fine, Assistant Principal Yuri Glukhovsky, Assistant Concertmaster Oleg Stolpner, Assistant Principal Barbara Schmutzler Percussion Marina Schwartz Boris Mihanovski Merav Askayo, Principal Vitali Remenuik Yaghi Malka Peled Contrabassoon Mitsunori Kambe Olga Fabricant Emilya Kazewman Rivkin Barbara Schmutzler Yonathan Givoni Michael -

COMPLETE PRELUDES Alexandra Dariescu FOREWORD

Vol . 1 COMPLETE PRELUDES Alexandra Dariescu FOREWORD I am delighted to present the first disc of a ‘Trilogy of Preludes’ containing the complete works of this genre of Frédéric Chopin and Henri Dutilleux. Capturing a musical genre from its conception to today has been an incredibly exciting journey. Chopin was the first composer to write preludes that are not what the title might suggest – introduction to other pieces – but an art form in their own right. Chopin’s set was the one to inspire generations and has influenced composers to the present day. Dutilleux’s use of polyphony, keyboard layout and harmony echoes Chopin as he too creates beauty though on a different level through his many colours and shaping of resonances. Recording the complete preludes of these two composers was an emotional roller coaster as each prelude has a different story to tell and as a whole, they go through every single emotion a human can possibly feel. Champs Hill Music Room provided the most wonderful forum for creating all of these moods. I am extremely grateful to our producer Matthew Bennett and sound engineer Dave Rowell, who were not only a fantastic team to work with but also an incredible source of information and inspiration. I would also like to express my sincere gratitude to Mary and David Bowerman and the entire team at Champs Hill for believing in me and making this project happen. Heartfelt thanks to photographer Vladimir Molico who captured the atmosphere Chopin found during the rainy winter of 1838 in Majorca through a modern adaptation of Renoir's Les Parapluies . -

Transformations of Programming Policies

The Warsaw Autumn International Festival of Contemporary Transformations of Programming Music Policies Małgorzata gąsiorowska Email: [email protected]???? Email: The Warsaw Autumn International Festival of Contemporary Music Transformations of Programming Policies Musicology today • Vol. 14 • 2017 DOI: 10.1515/muso-2017-0001 ABSTRACT situation that people have turned away from contemporary art because it is disturbing, perhaps necessarily so. Rather than The present paper surveys the history of the Warsaw Autumn festival confrontation, we sought only beauty, to help us to overcome the 1 focusing on changes in the Festival programming. I discuss the banality of everyday life. circumstances of organising a cyclic contemporary music festival of international status in Poland. I point out the relations between The situation of growing conflict between the bourgeois programming policies and the current political situation, which in the establishment (as the main addressee of broadly conceived early years of the Festival forced organisers to maintain balance between th Western and Soviet music as well as the music from the so-called art in the early 20 century) and the artists (whose “people’s democracies” (i.e. the Soviet bloc). Initial strong emphasis on uncompromising attitudes led them to question and the presentation of 20th-century classics was gradually replaced by an disrupt the canonical rules accepted by the audience and attempt to reflect different tendencies and new phenomena, also those by most critics) – led to certain critical situations which combining music with other arts. Despite changes and adjustments in marked the beginning of a new era in European culture. the programming policy, the central aim of the Festival’s founders – that of presenting contemporary music in all its diversity, without overdue In the history of music, one such symbolic date is 1913, emphasis on any particular trend – has consistently been pursued. -

Edison Denisov Contemporary Music Studies

Edison Denisov Contemporary Music Studies A series of books edited by Peter Nelson and Nigel Osborne, University of Edinburgh, UK Volume 1 Charles Koechlin (1867–1950): His Life and Works Robert Orledge Volume 2 Pierre Boulez—A World of Harmony Lev Koblyakov Volume 3 Bruno Maderna Raymond Fearn Volume 4 What’s the Matter with Today’s Experimental Music? Organized Sound Too Rarely Heard Leigh Landy Additional volumes in preparation: Stefan Wolpe Austin Clarkson Italian Opera Music and Theatre Since 1945 Raymond Fearn The Other Webern Christopher Hailey Volume 5 Linguistics and Semiotics in Music Raymond Monelle Volume 6 Music Myth and Nature François-Bernard Mache Volume 7 The Tone Clock Peter Schat Volume 8 Edison Denisov Yuri Kholopov and Valeria Tsenova Volume 9 Hanns Eisler David Blake Cage and the Human Tightrope David Revill Soviet Film Music: A Historical Perspective Tatyana Yegorova This book is part of a series. The publisher will accept continuation orders which may be cancelled at any time and which provide for automatic billing and shipping of each title in the series upon publication. Please write for details. Edison Denisov by Yuri Kholopov and Valeria Tsenova Moscow Conservatoire Translated from the Russian by Romela Kohanovskaya harwood academic publishers Australia • Austria • Belgium • China • France • Germany • India Japan • Malaysia • Netherlands • Russia • Singapore • Switzerland Thailand • United Kingdom • United States Copyright © 1995 by Harwood Academic Publishers GmbH. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Season 2010 Season 2010-2011

Season 20102010----20112011 The Philadelphia Orchestra Thursday, March 242424,24 , at 8:00 Friday, March 252525,25 , at 222:002:00:00:00 SaturSaturday,day, March 262626,26 , at 888:008:00:00:00 Stéphane Denève Conductor Imogen Cooper Piano Dutilleux Métaboles I. Incantatoire— II. Linéaire— III. Obsessionel— IV. Torpide— V. Flamboyant Mozart Piano Concerto No. 9 in E-flat major, K. 271 (“Jenamy”) I. Allegro II. Andantino III. Rondeau (Presto)—Menuetto (Cantabile)—Tempo primo Intermission Debussy Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun Roussel Symphony No. 3 in G minor, Op. 42 I. Allegro vivo II. Adagio—Più mosso—Adagio III. Vivace IV. Allegro con spirito This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes. The March 24 concert is sponsored by MEDCOMP. Stéphane Denève is chief conductor designate of the Stuttgart Radio Symphony (SWR), and takes up the position in September 2011. He is also music director of the Royal Scottish National Orchestra (RSNO), a post he has held since 2005. With that ensemble he has performed at the BBC Proms, the Edinburgh International Festival, and Festival Présences, and at venues throughout Europe, including Vienna’s Konzerthaus, Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw, and Paris’ Théatre des Champs-Élysées. Mr. Denève and the RSNO have made a number of acclaimed recordings together, including an ongoing survey of the works of Albert Roussel for Naxos. In 2007 they won a Diapason d'Or award for the first disc in the series. Highlights for Mr. Denève in the current season include a concert at the BBC Proms with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra and pianist Paul Lewis; his debut with the Bavarian Radio Symphony; return visits to the Philharmonia Orchestra, the Deutsches Symphonieorchester Berlin, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Toronto Symphony, the New World Symphony, and the Hong Kong Philharmonic; and his debut at the Gran Teatre de Liceu in Barcelona, conducting Dukas’s Ariane et Barbe-bleue.