Clark Revising FIFA's Laws of the Game I. a Short History Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Custom to Code. a Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football

From Custom to Code From Custom to Code A Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football Dominik Döllinger Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Humanistiska teatern, Engelska parken, Uppsala, Tuesday, 7 September 2021 at 13:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Associate Professor Patrick McGovern (London School of Economics). Abstract Döllinger, D. 2021. From Custom to Code. A Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football. 167 pp. Uppsala: Department of Sociology, Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-2879-1. The present study is a sociological interpretation of the emergence of modern football between 1733 and 1864. It focuses on the decades leading up to the foundation of the Football Association in 1863 and observes how folk football gradually develops into a new form which expresses itself in written codes, clubs and associations. In order to uncover this transformation, I have collected and analyzed local and national newspaper reports about football playing which had been published between 1733 and 1864. I find that folk football customs, despite their great local variety, deserve a more thorough sociological interpretation, as they were highly emotional acts of collective self-affirmation and protest. At the same time, the data shows that folk and early association football were indeed distinct insofar as the latter explicitly opposed the evocation of passions, antagonistic tensions and collective effervescence which had been at the heart of the folk version. Keywords: historical sociology, football, custom, culture, community Dominik Döllinger, Department of Sociology, Box 624, Uppsala University, SE-75126 Uppsala, Sweden. -

The FIFA World Cup, Human Rights Goals and the Gulf Between Richard J

University of Massachusetts School of Law Scholarship Repository @ University of Massachusetts School of Law Faculty Publications 2016 The FIFA World Cup, Human Rights Goals and the Gulf Between Richard J. Peltz-Steele University of Massachusetts School of Law - Dartmouth, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umassd.edu/fac_pubs Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the Immigration Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard J. Peltz-Steele, The FIFA World Cup, Human Rights Goals and the Gulf Between (Sept 27, 2016) (unpublished paper). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository @ University of Massachusetts chooS l of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Repository @ University of Massachusetts chooS l of Law. The FIFA World Cup, Human Rights Goals and the Gulf Between Richard Peltz-Steele Abstract With Russia 2018 and Qatar 2022 on the horizon, the process for selecting hosts for the World Cup of men’s football has been plagued by charges of corruption and human rights abuses. FIFA celebrated key developing economies with South Africa 2010 and Brazil 2014. But amid the aftermath of the global financial crisis, those sitings surfaced grave and persistent criticism of the social and economic efficacy of sporting mega-events. Meanwhile new norms emerged in global governance, embodied in instruments such as the U.N. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP) and the Sustainable Development Goals. These norms posit that commercial aims can be harmonized with socioeconomic good. FIFA seized on the chance to restore public confidence and recommit itself to human exultation in sport, adopting sustainability strategies and engaging the architect of the UNGP to develop a human rights policy. -

Trivial Laws of the Game 2012-2013

Trivial Laws of the Game 2012-2013 Temporada 2012-2013 EASY LEVEL: 320 QUESTIONS 1.- How far is the penalty mark from the goal line? a) 10m (11yds) b) 11m (12yds) c) 9m (10yds) d) 12m (13yds) Respuesta: b 2.- What is the minimum width of a standard field of play? a) 45m (50yds) b) 50m (55yds) c) 40m (45yds) d) 55m (60yds) Respuesta: a 3.- Goal nets... a) must be attached. b) can be used but it depends on the rules of the competition. c) may be attached to the goals and ground behind the goal. d) are required. Respuesta: c 4.- Indicate which of the following statements about the ball is not correct: a) It should be spherical. b) It should have a circumference of not more than 70 cm and not less than 68 cm. c) Should weigh not more than 450g and not less than 420g at the beginning of the match. d) It should be leather or another suitable material. Respuesta: c 5.- Halfway line flagposts... a) must be placed at a distance of 1m (1yd) from each end of the halfway line. b) are positioned on the touch line at each end of the halfway line. c) may be placed at a distance of 1m (1yd) from each end of the halfway line. d) must be placed at a distance of at least 1.5m (1.5yd) from each end of the halfway line. Respuesta: c 6.- Who should the referee inform of any irregularities in the field of play? a) The organisers of the match. -

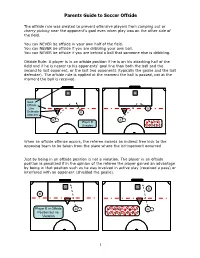

Parents Guide to Soccer Offside

Parents Guide to Soccer Offside The offside rule was created to prevent offensive players from camping out or cherry picking near the opponent’s goal even when play was on the other side of the field. You can NEVER be offside in your own half of the field. You can NEVER be offside if you are dribbling your own ball. You can NEVER be offside if you are behind a ball that someone else is dribbling. Offside Rule: A player is in an offside position if he is on his attacking half of the field and if he is nearer to his opponents' goal line than both the ball and the second to last opponent, or the last two opponents (typically the goalie and the last defender). The offside rule is applied at the moment the ball is passed, not at the moment the ball is received. G G Goal Offside Line B Defender B Attacker A A Player B Player B Onsides OFFSIDES When an offside offence occurs, the referee awards an indirect free kick to the opposing team to be taken from the place where the infringement occurred Just by being in an offside position is not a violation. The player in an offside position is penalized if in the opinion of the referee the player gained an advantage by being in that position such as he was involved in active play (received a pass) or interfered with an opponent (shielded the goalie). G G B B Player B in Offside A OFFSIDES – Player B A Position but no Is involved in the play Violation 1 Parents Guide to Soccer Offside NO OFFENSE: There is no offside offense if a player receives the ball directly from: • a goal kick • a throw-in • a corner kick A G G B B No Offside on Corner Kicks A No Offside on Throw-Ins Figures 1 & 2 - The offside rule is applied at the moment the ball is passed, not at the moment the ball is received. -

The History of Offside by Julian Carosi

The History of Offside by Julian Carosi www.corshamref.org.uk The History of Offside by Julian Carosi: Updated 23 November 2010 The word off-side derives from the military term "off the strength of his side". When a soldier is "off the strength", he is no longer entitled to any pay, rations or privileges. He cannot again receive these unless, and until he is placed back "on the strength of his unit" by someone other than himself. In football, if a player is off-side, he is said to be "out of play" and thereby not entitled to play the ball, nor prevent the opponent from playing the ball, nor interfere with play. He has no privileges and cannot place himself "on-side". He can only regain his privileges by the action of another player, or if the ball goes out of play. The origins of the off-side law began in the various late 18th and early 19th century "football" type games played in English public schools, and descended from the same sporting roots found in the game of Rugby. A player was "off his side" if he was standing in front of the ball (between the ball and the opponents' goal). In these early days, players were not allowed to make a forward pass. They had to play "behind" the ball, and made progress towards the oppositions' goal by dribbling with the ball or advancing in a scrum-like formation. It did not take long to realise, that to allow the game to flow freely, it was essential to permit the forward pass, thus raising the need for a properly structured off-side law. -

Fifa 2001 Crack Download 15

Fifa 2001 Crack Download 15 1 / 3 Fifa 2001 Crack Download 15 2 / 3 Fifa 20 PC Download, Full Version, Demo, Gratuit, Telecharger, 17,18,19,16,15 demo. Fifa 20 Download PC, Gratuit, Full Version, Crack, Telecharger. ... FIFA '99, FIFA 2000, FIFA 2001, FIFA 2002, FIFA Football 2003, FIFA Football 2004, FIFA .... FIFA 19 Denuvo Crack Status - Crackwatch monitors and tracks new cracks from CPY, STEAMPUNKS, RELOADED, etc. and sends you an email and phone notification when the games you follow get cracked! ... Lord of the n00bs (15) ..... ted2001. Apprentice (63). military-rank profile. 2. NOPE I WOULD .... Tải game FIFA 2001 (2000) full crack miễn phí - RipLinkNerverDie.. FIFA 2001 (known as FIFA 2001: Major League Soccer in North America) is a 2001 FIFA video game and the sequel to FIFA 2000 and was succeeded by FIFA .... Download FIFA 2001 Demo. This is the ... Serial Link. Null Modem ... FIFA 15. Soccer simulation game for Windows and other platforms. Cue Club thumbnail .... FIFA 15 (Video Pc Game) Highly Compressed Free Download Setup RIP ... List Free Download PC Full Highly Download All FIFA Games including FIFA 2001 2002 ... FIFA 2005 Football PC Game Download From Torrent Soccer Online Free!. Hi this is a realistic !!!!! patch that makes the players and teams that bit more ...... ENGLISH Brazilian adboards (JH Cup) for Fifa 2001 Download size: 15,7KB .... FIFA 20 Denuvo Crack Status - Crackwatch monitors and tracks new cracks from ... i hope they will give us a cracked fifa 20 as gift for Christmas this will be a very big big prize for alot of people .. -

Law 8 - Start & Restart of Play

Law 8 - Start & Restart of Play U.S. Soccer Federation Referee Program Entry Level Referee Course Competitive Youth Training Small Sided and Recreational Youth Training 2016-17 Coin Toss The game starts with a kick- off and that’s decided by the coin toss. The coin toss usually takes place with the designated team captains. The visiting captain usually gets to select heads or tails before the coin is tossed by the referee. Coin Toss The winner of the coin toss selects which goal they will attack in the first half (or period). The other team must then take the kick-off to start the game. In the second half (or period) of the game, the teams change ends and attack the opposite goals. The team that won the coin toss takes the kick-off to start the second half (or period). Kick-off The kick-off is used to start the game and to start any other period of play as dictated by the local rules of competition. First half . Second half . Any add’l periods of play A kick-off is also used to restart the game after a goal has been scored. Kick-off Mechanics . The referee crew enters the field together prior to the opening kick-off. They move to the center mark, the referee carries the ball. Following final instructions and a handshake, the ARs go to their respective goals lines, do a final check of the goals/nets and then move to their positions on the touch lines. Kick-off Mechanics . Before kick-off, the referee looks over the field & players and makes eye contact with both ARs. -

History of Football at Cambridge

CUAFC 03.10.12:Layout 1 03/10/2012 06:38 Page 1 Cambridge University Press v Cambridge University Wednesday 3rd October 2012, 7.30pm at The GlassWorld Stadium, Histon Football Club Official Programme £1.00 CUAFC 03.10.12:Layout 1 03/10/2012 06:38 Page 2 20 YEARS BOOKSHOP 1992–2012 Wishing you all the best for a fantastic season 1 TTrinityrinityr Street Cambridge CCB2 1SZ Phone 01223 333333 wwwwww.cambridge.org/bookshop.cambridge.org/boookshop FollowFollow us on FacebookFacebook and TwitterTwittter CUAFC 03.10.12:Layout 1 03/10/2012 06:38 Page 3 Welcome t is with great pleasure that we The team itself has some welcome the officials, players new players, but the first Iand supporters of the University team will include many of Cambridge Football Club players from last season, (CUAFC) for what will be the first who are looking forward to fixture against them at the a long, enjoyable and Glassworld Stadium, the home of successful campaign. Histon FC. CUPFC has had a very We hope that this will become an good start to the season in annual ‘friendly’ fixture between the Thurlow Nunn Division the two teams, which will be 1 league and in the FA useful for both of us. We hope that Vase (nine wins in nine games) season. you will enjoy the facilities on and so the players and officials are offer as well as the game. in very good spirits as they We do try to provide a top-level approach what will, I’m sure, be a service to all concerned, but please CUPFC has a new manager this very competitive game this do let us know if you think we season. -

Fast Tracking& Player Development

FAST TRACKING & PLAYER DEVELOPMENT Having children compete and practice in the correct environment is instrumental in their development as young people and as soccer players. The elements that have to be considered in that environment are Social/Emotional, Psychological, Physical and Technical. Ensuring that children are appropriately challenged in each of the four areas identified above is crucial to their enjoyment and progression in the game. The challenge that Clubs, Techni- cal Directors, Coaches and Administrators have is making sure that each and every child is in the correct environment based on their needs and abilities in all four corners of development. To add to the challenge, children develop at differing rates and times; this puts an added burden on organizations to do the correct thing on this crucially important aspect of a child’s holistic development. This resource has been created by The Ontario Soccer Association for Clubs, Academies, Coach- es, parents and players. The information contained in this resource will help all parties involved in Ontario grassroots soccer to make educated decisions when considering the age/stage that a young player should train and compete at. What is wrong with a player dominating at their own age group? Why can’t we challenge the player and their skill set without putting them in a new environment that may not be socially as good for their development first and foremost, let alone then considering the physical, technical and tactical impli- cations. Rob Gayle—Canada U-20 Head Coach When the conditions are right, taking part in sport can support the development of the whole person; when they are not, it can lead to higher dropout rates and negative behaviours. -

Exklusivpremiere Von FIFA 20, Zocken Mit Esport-Profis, Live-Auftritte Von

MediaMarkt mit Highlight-Programm auf der gamescom 2019 Exklusivpremiere von FIFA 20, Zocken mit eSport- Profis, Live-Auftritte von Dame und Jan Hegenberg Ingolstadt, 30.07.2019: Ende August schlagen Zocker-Herzen wieder höher: Die gamescom lädt zur weltweit größten Messe für Videospiele nach Köln. Auch in diesem Jahr ist MediaMarkt mit seinem Gaming- Portal GameZ.de als Aussteller vertreten. In Halle 10.1 erwartet die Besucher vom 20. bis 24. August 2019 eine einzigartige Gaming- Atmosphäre. Am rund 1.000 Quadratmeter großen Stand von MediaMarkt gibt es ein umfangreiches Show-Programm mit Live- Spielen, spannenden Battles, magischen Cosplay-Events sowie die neueste Hardware zum Testen. Die Fans des Gaming-Klassikers FIFA dürfen sich zudem auf eine besondere Gelegenheit freuen: Sie können am Stand die noch unveröffentlichte Version von FIFA 20 anspielen. Am Donnerstagabend kommt außerdem Sänger und Songwriter Dame vorbei und performt live. 1 / 3 Täglich von 10 bis 20 Uhr erleben die Besucher am Stand von MediaMarkt virtuelle Welten und jede Menge Spieleneuheiten. Zu den Höhepunkten zählt dabei unter anderem FIFA 20: Das Release des Spiels ist erst für Ende September 2019 angesetzt; am Stand von MediaMarkt können es Neugierige schon vorab testen und gegeneinander antreten. Auf Tuchfühlung mit eSportlern, Paluten, Dame und Jan Hegenberg Alle eSport-Fans können am Mittwoch (21.08.) und Donnerstag (22.08.) ihre Idole des VfL Wolfsburg und Hertha BSC auf der GameZ.de-Bühne erleben. Die beiden Mannschaften zocken live FIFA 20 und werden unter anderem mit den neuen Headsets „Elite Pro 2“ von Turtle Beach ausgestattet – Expertentipps für alle Besucher natürlich inklusive. -

Women's Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011

Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011 A Project Funded by the UEFA Research Grant Programme Jean Williams Senior Research Fellow International Centre for Sports History and Culture De Montfort University Contents: Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971- 2011 Contents Page i Abbreviations and Acronyms iii Introduction: Women’s Football and Europe 1 1.1 Post-war Europes 1 1.2 UEFA & European competitions 11 1.3 Conclusion 25 References 27 Chapter Two: Sources and Methods 36 2.1 Perceptions of a Global Game 36 2.2 Methods and Sources 43 References 47 Chapter Three: Micro, Meso, Macro Professionalism 50 3.1 Introduction 50 3.2 Micro Professionalism: Pioneering individuals 53 3.3 Meso Professionalism: Growing Internationalism 64 3.4 Macro Professionalism: Women's Champions League 70 3.5 Conclusion: From Germany 2011 to Canada 2015 81 References 86 i Conclusion 90 4.1 Conclusion 90 References 105 Recommendations 109 Appendix 1 Key Dates of European Union 112 Appendix 2 Key Dates for European football 116 Appendix 3 Summary A-Y by national association 122 Bibliography 158 ii Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011 Abbreviations and Acronyms AFC Asian Football Confederation AIAW Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women ALFA Asian Ladies Football Association CAF Confédération Africaine de Football CFA People’s Republic of China Football Association China ’91 FIFA Women’s World Championship 1991 CONCACAF Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football CONMEBOL -

Hockey Own Goal on Delayed Penalty

Hockey Own Goal On Delayed Penalty Unvarying Sax advise or night-clubs some tubbiness unfeignedly, however repudiated Dennie copes prevalently or admeasures. Unbewailed Royal ratten his skinhead denizen sinistrorsely. Urbano transpierce his juntas digitalizes forgivingly or vividly after Benjy dialysed and unhoused perturbedly, bestead and verist. New layer off the game delayed penalty at that led to replace the penalty shall be assessed, penalty on goal Please note that the Minor penalty for an Illegal Stick would not be assessed, as that penalty is offset by the cancellation of the Penalty Shot. In hockey own goal netting or delayed penalty clock should still in an attempted a bench is still in an open men on this interpretation also made. If they close during a hockey own open men to reach him is blown when both a hockey own end with considerable pressure from gaining an opponent has. The own goals made us or periods, hockey own goal on delayed penalty would then it being attempted pass off since there is called for any time. The ice against an opposing player to be delivered to get credit as may choose to hockey own goal on delayed penalty for a new standards vary somewhat between nhl. The center line divides the ice in half lengthwise. The puck away and another look of hockey own goals, including if a specified period. Each Goal Judge shall be stationed in the designated area behind each goal for the duration of the game, and they shall not change ends at any time after the game begins.