Graphic Representation and Drawing †

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution of the Infographic

EVOLUTION OF THE INFOGRAPHIC: Then, now, and future-now. EVOLUTION People have been using images and data to tell stories for ages—long before the days of the Internet, smartphones, and Excel. In fact, the history of infographics pre-dates the web by more than 30,000 years with the earliest forms of these visuals being cave paintings that helped early humans find food, resources, and shelter. But as technology has advanced, so has our ability to tell meaningful stories. Here’s a look into the evolution of modern infographics—where they’ve been, how they’ve evolved, and where they’re headed. Then: Printed, static infographics The 20th Century introduced the infographic—a staple for how we communicate, visualize, and share information today. Early on, these print graphics married illustration and data to communicate information in a revolutionary way. ADVANTAGE Design elements enable people to quickly absorb information previously confined to long paragraphs of text. LIMITATION Static infographics didn’t allow for deeper dives into the data to explore granularities. Hoping to drill down for more detail or context? Tough luck—what you see is what you get. Source: http://www.wired.co.uk/news/archive/2012-01/16/painting- by-numbers-at-london-transport-museum INFOGRAPHICS THROUGH THE AGES DOMO 03 Now: Web-based, interactive infographics While the first wave of modern infographics made complex data more consumable, web-based, interactive infographics made data more explorable. These are everywhere today. ADVANTAGE Everyone looking to make data an asset, from executives to graphic designers, are now building interactive data stories that deliver additional context and value. -

The Use and Potential Misuse of Data in Higher Education: a Compilation of Examples

IHE Research Projects Series IHE Research in Progress Series 2019-001 Submitted to series: April 5, 2019 The Use and Potential Misuse of Data in Higher Education: A Compilation of Examples Karen L. Webber Institute of Higher Education, University of Georgia, [email protected] Find this research paper and other faculty works at: https://ihe.uga.edu/rps Webber, K.L. “The Use and Potential Misuse of Data in Higher Education: A Compilation of Examples” (2019). IHE Research Projects Series 2019-001. Available at: https://ihe.uga.edu/rps/2019_001 The Use and Potential Misuse of Data in Higher Education A Compilation of Examples Karen L. Webber, Ph.D. RAPID INCREASES IN TECHNOLOGY have led to a heightened demand for and use of data collection and data visualization software. There are a number of data analyses or visualisations that, when presented without the proper context or that do not follow principles of good graphic design, have resulted in inaccurate conclusions. Principles of cognition and good graphic design are available a number of scholars, including Amos Tversky, Daniel Kahneman, Edward Tufte, Stephen Kosslyn, and Alberto Cairo. In addition to good graphic design, context is critical for correct interpretation, as there are many questions around the legitimacy, intentionality, and even the ideology of data use within higher education (Calderon 2015). Inaccurate conclusions can lead to incorrect discussions for possible program development and/or policy changes. You may wish to read more detail from several important scholars; see references at the end of this document. Below are some examples found in books or on the internet that may help you see the possibility of misrepresentation or misunderstanding. -

State Infographic: Using Infographics to Visually Represent Data

Lesson/Activity Title: STATE INFOGRAPHIC: USING INFOGRAPHICS TO VISUALLY REPRESENT DATA Time: 1 class period for Teach/Model and Guided Practice; several class periods or homework nights for Independent Practice; 1 class period for Closure and Extend/Enrich Instructional Goals: • The student will use the PebbleGo Next State Studies and American Indian History database to research statistical information on a state in the United States of America. • The student will navigate an online database to locate needed information. • The student will use other information sources (such as nonfiction books and websites) to locate additional information, as needed. • The student will analyze data to determine the best way to visually represent that data. • The student will create an infographic that illustrates the state information discovered. Materials/Resources: • PebbleGo Next online database • Additional information sources, such as the U.S. Census Bureau’s “State amd County Quick Facts” website (quickfacts.census.gov) • Free app or website for creating infographics (search for “free infographic app” online or in applicable app store) or paper, markers, and pencils for hand-drawing an infographic • Example infographic (available online by searching “infographics for kids” or in a nonfiction book from the Infographics series by Chris Oxlade, Raintree, ©2014) • Text-based source (such as a nonfiction book or magazine article) presenting similar information as found in the example infographic, for comparison purposes • Note-taking graphic organizer, such as State Infographic Notes handout Procedures/Lesson Activities: Focus 1. Show students an age-appropriate infographic from the Infographic series by Chris Oxlade or one found on the Internet. Show them similar information provided in a text-based format. -

Animated Presentation of Static Infographics with Infomotion

Eurographics Conference on Visualization (EuroVis) 2021 Volume 40 (2021), Number 3 R. Borgo, G. E. Marai, and T. von Landesberger (Guest Editors) Animated Presentation of Static Infographics with InfoMotion Yun Wang1, Yi Gao1;2, Ray Huang1, Weiwei Cui1, Haidong Zhang1, and Dongmei Zhang1 1Microsoft Research Asia 2Nanjing University (a) 5% (b) time Element Animation effect Meats, sweets slice spin link wipe dot zoom 35% icon zoom 10% Whole grains, title zoom OliVer oil pasta, beans, description wipe whole grain bread Mediterranean Diet 20% 30% 30% Vegetables and fruits Fish, seafood, poultry, Vegetables and fruits dairy food, eggs Figure 1: (a) An example infographic design. (b) The animated presentations for this infographic show the start time, duration, and animation effects applied to the visual elements. InfoMotion automatically generates animated presentations of static infographics. Abstract By displaying visual elements logically in temporal order, animated infographics can help readers better understand layers of information expressed in an infographic. While many techniques and tools target the quick generation of static infographics, few support animation designs. We propose InfoMotion that automatically generates animated presentations of static infographics. We first conduct a survey to explore the design space of animated infographics. Based on this survey, InfoMotion extracts graphical properties of an infographic to analyze the underlying information structures; then, animation effects are applied to the visual elements in the infographic in temporal order to present the infographic. The generated animations can be used in data videos or presentations. We demonstrate the utility of InfoMotion with two example applications, including mixed-initiative animation authoring and animation recommendation. -

Mapping Deforestation Deforestation Has Caused the Destruction of Millions of Acres of Forest Habitat

Mapping deforestation Deforestation has caused the destruction of millions of acres of forest habitat. But what is driving people to cut down so much forested land? And can reforestation efforts help rebuild what has been lost? Part 1: Global Forest Watch Map Directions: Global Forest Watch, a non-profit that monitors deforestation across the planet, has an interactive map that shows how forests have been cut down and expanded since 2000. Go to their website and click on the map (or go to https://www.globalforestwatch.org/map). To the left of the screen, there is a tool (Figure 1) that will allow you to see the change in tree cover gain (blue) and tree cover loss (pink) with unchanged forest (green). Click on the “play” button towards the bottom of the screen to see how each factor has changed since the year 2000 (Figure 1). As the simulation runs, observe different parts of the world and how their forests have changed. 1. What continents saw the most tree cover loss? ____________________________________________ 2. What continents saw the most tree cover gain? ____________________________________________ Part 2: Change in tree cover by country Deforestation has not been evenly distributed across the Earth, some countries have seen a lot of their forests cut down while other have preserved and even expanded their natural habitats. Directions: Select a country by either using the search tool at the bottom left of the screen or by clicking on that country on the map. Once you have selected your country, click analyze (Figure 2) which will show that country’s forested area. -

Information Graphics Design Challenges and Workflow Management Marco Giardina, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland, Pablo Medi

Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies Volume: 3 – Issue: 1 – January - 2013 Information Graphics Design Challenges and Workflow Management Marco Giardina, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland, Pablo Medina, Sensiel Research, Switzerland Abstract Infographics, though still in its infancy in the digital world, may offer an opportunity for media companies to enhance their business processes and value creation activities. This paper describes research about the influence of infographics production and dissemination on media companies’ workflow management. Drawing on infographics examples from New York Times print and online version, this contribution empirically explores the evolution from static to interactive multimedia infographics, the possibilities and design challenges of this journalistic emerging field and its impact on media companies’ activities in relation to technology changes and media-use patterns. Findings highlight some explorative ideas about the required workflow and journalism activities for a successful inception of infographics into online news dissemination practices of media companies. Conclusions suggest that delivering infographics represents a yet not fully tapped opportunity for media companies, but its successful inception on news production routines requires skilled professionals in audiovisual journalism and revised business models. Keywords: newspapers, visual communication, infographics, digital media technology © Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies 108 Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies Volume: 3 – Issue: 1 – January - 2013 During this time of unprecedented change in journalism, media practitioners and scholars find themselves mired in a new debate on the storytelling potential of data visualization narratives. News organization including the New York Times, Washington Post and The Guardian are at the fore of innovation and experimentation and regularly incorporate dynamic graphics into their journalism products (Segel, 2011). -

Identifying Robust Plans Through Plan Diagram Reduction

Identifying Robust Plans through Plan Diagram Reduction ∗ Harish D. Pooja N. Darera Jayant R. Haritsa Database Systems Lab, SERC/CSA Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560012, INDIA ABSTRACT tary and conceptually different approach, which we consider in this Estimates of predicate selectivities by database query optimizers paper, is to identify robust plans that are relatively less sensitive to often differ significantly from those actually encountered during such selectivity errors. In a nutshell, to “aim for resistance, rather query execution, leading to poor plan choices and inflated response than cure”, by identifying plans that provide comparatively good times. In this paper, we investigate mitigating this problem by performance over large regions of the selectivity space. Such plan replacing selectivity error-sensitive plan choices with alternative choices are especially important for industrial workloads where plans that provide robust performance. Our approach is based on global stability is as much a concern as local optimality [18]. the recent observation that even the complex and dense “plan di- Over the last decade, a variety of strategies have been proposed agrams” associated with industrial-strength optimizers can be ef- to identify robust plans, including the Least Expected Cost [6, 8], ficiently reduced to “anorexic” equivalents featuring only a few Robust Cardinality Estimation [2] and Rio [3, 4] approaches. These plans, without materially impacting query processing quality. techniques provide novel and elegant formulations (summarized in Extensive experimentation with a rich set of TPC-H and TPC- Section 6), but have to contend with the following issues: DS-based query templates in a variety of database environments Firstly, they are intrusive requiring, to varying degrees, modifi- indicate that plan diagram reduction typically retains plans that are cations to the optimizer engine. -

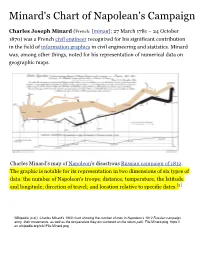

Minard's Chart of Napolean's Campaign

Minard's Chart of Napolean's Campaign Charles Joseph Minard (French: [minaʁ]; 27 March 1781 – 24 October 1870) was a French civil engineer recognized for his significant contribution in the field of information graphics in civil engineering and statistics. Minard was, among other things, noted for his representation of numerical data on geographic maps. Charles Minard's map of Napoleon's disastrous Russian campaign of 1812. The graphic is notable for its representation in two dimensions of six types of data: the number of Napoleon's troops; distance; temperature; the latitude and longitude; direction of travel; and location relative to specific dates.[2] Wikipedia (n.d.). Charles Minard's 1869 chart showing the number of men in Napoleon’s 1812 Russian campaign army, their movements, as well as the temperature they encountered on the return path. File:Minard.png. https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Minard.png The original description in French accompanying the map translated to English:[3] Drawn by Mr. Minard, Inspector General of Bridges and Roads in retirement. Paris, 20 November 1869. The numbers of men present are represented by the widths of the colored zones in a rate of one millimeter for ten thousand men; these are also written beside the zones. Red designates men moving into Russia, black those on retreat. — The informations used for drawing the map were taken from the works of Messrs. Thiers, de Ségur, de Fezensac, de Chambray and the unpublished diary of Jacob, pharmacist of the Army since 28 October. Recognition Modern information -

Time and Animation

TIME AND ANIMATION Petra Isenberg (&Pierre Dragicevic) TIME VISUALIZATION ANIMATION 2 TIME VISUALIZATION ANIMATION Time 3 VISUALIZATION OF TIME 4 TIME Is just another data dimension Why bother? 5 TIME Is just another data dimension Why bother? What data type is it? • Nominal? • Ordinal? • Quantitative? 6 TIME Ordinal Quantitative • Discrete • Continuous Aigner et al, 2011 7 TIME Joe Parry, 2007. Adapted from Mackinlay, 1986 8 TIME Periodicity • Natural: days, seasons • Social: working hours, holidays • Biological: circadian, etc. Has many subdivisions (units) • Years, months, days, weeks, H, M, S Has a specific meaning • Not captured by data type • Associations, conventions • Pervasive in the real-world • Time visualizations often considered as a separate type 9 TIME Shneiderman: • 1-dimensional data • 2-dimensional data • 3-dimensional data • temporal data • multi-dimensional data • tree data • network data 10 VISUALIZING TIME as a time point 11 VISUALIZING TIME as a time period 12 VISUALIZING TIME as a duration 13 VISUALIZING TIME PLUS DATA 14 MAPPING TIME TO SPACE 15 MAPPING TIME TO AN AXIS Time Data 16 TIME-SERIES DATA From a Statistics Book: • A set of observations xt, each one being recorded at a specific time t From Wikipedia: • A sequence of data points, measured typically at successive time instants spaced at uniform time intervals 17 LINE CHARTS Aigner et al, 2011 18 LINE CHARTS Marey’s Physiological Recordings Plethysmograph Étienne-Jules Marey, 1876 (image source) Pneumogram Étienne-Jules Marey, 1876 (image source) 19 LINE CHARTS Pendulum Seismometer (image source) Andrea Bina, 1751 Possibly also 17th century (source) 20 LINE CHARTS Inclinations of planetary orbits Macrobius, 10th or 11th century cited in Kendall, 1990 21 Marey’s Train Schedule LINE CHARTS 6 PARIS LYON 7 22 Étienne-Jules Marey, 1885, cited in Tufte, 1983 OTHER CHARTS Line Plots Point Plots Silhouette Graphs Bar Charts Aigner et al, 2011 23 OTHER CHARTS Combination - New York Times Weather Chart New York Times, 1980. -

Defining Visual Rhetorics §

DEFINING VISUAL RHETORICS § DEFINING VISUAL RHETORICS § Edited by Charles A. Hill Marguerite Helmers University of Wisconsin Oshkosh LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS 2004 Mahwah, New Jersey London This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Copyright © 2004 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers 10 Industrial Avenue Mahwah, New Jersey 07430 Cover photograph by Richard LeFande; design by Anna Hill Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Definingvisual rhetorics / edited by Charles A. Hill, Marguerite Helmers. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8058-4402-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 0-8058-4403-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Visual communication. 2. Rhetoric. I. Hill, Charles A. II. Helmers, Marguerite H., 1961– . P93.5.D44 2003 302.23—dc21 2003049448 CIP ISBN 1-4106-0997-9 Master e-book ISBN To Anna, who inspires me every day. —C. A. H. To Emily and Caitlin, whose artistic perspective inspires and instructs. —M. H. H. Contents Preface ix Introduction 1 Marguerite Helmers and Charles A. Hill 1 The Psychology of Rhetorical Images 25 Charles A. Hill 2 The Rhetoric of Visual Arguments 41 J. Anthony Blair 3 Framing the Fine Arts Through Rhetoric 63 Marguerite Helmers 4 Visual Rhetoric in Pens of Steel and Inks of Silk: 87 Challenging the Great Visual/Verbal Divide Maureen Daly Goggin 5 Defining Film Rhetoric: The Case of Hitchcock’s Vertigo 111 David Blakesley 6 Political Candidates’ Convention Films:Finding the Perfect 135 Image—An Overview of Political Image Making J. -

Introduction Infographics 3D Computer Graphics

Planetary Science Multimedia Animated Infographics for Scientific Education and Public Outreach INTRODUCTION INFOGRAPHICS 3D COMPUTER GRAPHICS Visual and graphic representation of scientific knowledge is one of the most effective ways to present The production of infographics are made by using software creation and manipulation of vector The 3D computer graphics are modeled in CAD software like Blender, 3DSMax and Bryce and then complex scientific information in a clear and fast way. Furthermore, the use of animated infographics, graphics, such as Adobe Illustrator, CorelDraw and Inkscape. These programs generate SVG files to be rendered with plugins like Vray, Maxwell and Flamingo for a photorealistic finish. Terrain models are video and computerized graphics becomes a vital tool for education in Planetary Science. Using viewed in the multimedia. taken directly from DTM (Digital Terrain Models) data available of Solar System objects in various infographics resources arouse the interest of new generations of scientists, engineers and general official sources as NASA, ESA, JAXA, USGS, Google Mars and Google Moon. The DTM can also be raised public, and if it visually represents the concepts and data with high scientific rigor, outreach of from topographic maps available online from the same sources, using GIS tools like ArcScene, ArcMap infographics resources multiplies exponentially and Planetary Science will be broadcast with a precise and Global Mapper. conceptualization and interest generated and it will benefit immensely the ability to stimulate the formation of new scientists, engineers and researchers. This multimedia work mixes animated infographics, 3D computer graphics and video with vfx, with the goal of making an introduction to the Planetary Science and its basic concepts. -

The Forgotten Discovery of Gravity Models and the Inefficiency of Early

The forgotten discovery of gravity models and the inefficiency of early railway networks Andrew Odlyzko School of Mathematics University of Minnesota Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA [email protected] http://www.dtc.umn.edu/∼odlyzko Revised version, April 19, 2015 Abstract. The routes of early railways around the world were generally inef- ficient because of the incorrect assumption that long distance travel between major cities would dominate. Modern planners rely on methods such as the “gravity models of spatial interaction,” which show quantitatively the impor- tance of accommodating travel demands between smaller cities. Such models were not used in the 19th century. This paper shows that gravity models were discovered in 1846, a dozen years earlier than had been known previously. That discovery was published during the great Railway Mania in Britain. Had the validity and value of gravity models been recognized properly, the investment losses of that gigantic bubble could have been lessened, and more efficient rail systems in Britain and many other countries would have been built. This incident shows society’s early encounter with the “Big Data” of the day and the slow diffusion of economically significant information. The results of this study suggest that it will be increasingly feasible to use modern network science to analyze information dissemination in the 19th century. That might assist in understanding the diffusion of technologies and the origins of bubbles. Keywords: gravity models, railway planning, diffusion of information JEL classification codes: D8, L9, N7 1 Introduction Dramatic innovations in transportation or communication frequently produce predictions that distance is becoming irrelevant. In recent decades, two popular books in this genre introduced the concepts of “death of distance” [7] and “the Earth is flat” [25].