An Introduction to Inequality of Race, Wealth, and Class, Equality of Opportunity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Board Committee Academic Policy Documents B5 1

Board of Trustees of The City University of New York RESOLUTION I.B.5 TO Award an Honorary Degree at Commencement by the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism October 7, 2019 WHEREAS, journalist Masha Gessen is one of the keenest investigative reporters and observers of Russian politics and culture, as well as the present world of political life in the United States; and WHEREAS, Gessen, a staff writer at the New Yorker, is the author of ten books and countless articles for a variety of top journalistic outlets, including Slate, The New York Times, Vanity Fair, Harper’s, The New York Review of Books, U.S. News & World Report, and The New Republic; and WHEREAS, their publications have been acknowledged with numerous awards, fellowships and other honors, including the 2017 National Book Award for The Future is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia; and WHEREAS, the Newmark Graduate School of Journalism is committed to serving the public interest by cultivating the next generation of skilled, ethically minded, and diverse journalists, and Gessen represents the values to which the Newmark J-School holds true, and to which we hope our graduates aspire; and WHEREAS, in granting this degree, the Newmark J-School will recognize Gessen's extensive contributions to our understanding of Russia and the importance of free expression through insightful and provocative books, essays, and articles; and WHEREAS, the honorary degree will also recognize their commitment to a robust democratic life, an informed electorate, and an active fourth estate; and WHEREAS, with the Newmark's J-School's emphasis on investigative reporting and the importance of strong journalism that stands up to tyranny, Gessen is an ideal candidate for the first-ever honorary CUNY degree from the J-School NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED, That the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY award Masha Gessen the degree of Doctor of Humane Letters, honoris causa, at the school’s commencement ceremony on December 13, 2019. -

EXPERIMENT: a Manifesto of Young England, 1928- 1931 Two Volumes

EXPERIMENT: A Manifesto of Young England, 1928- 1931 Two Volumes Vol. 2 of 2 Kirstin L. Donaldson PhD University of York History of Art September 2014 Table of Conents Volume Two Appendix: Full Transcript of Experiment Experiment 1 (November 1928) 261 Experiment 2 (February 1929) 310 Experiment 3 (May 1929) 358 Experiment 4 (November 1929) 406 Experiment 5 (February 1930) 453 Experiment 6 (October 1930) 501 Experiment 7 (Spring 1931) 551 260 EXPERIMENT We are concerned with all the intellectual interests of undergraduates. We do not confine ourselves to the work of English students, nor are we at pains to be littered with the Illustrious Dead and Dying. Our claim has been one of uncompromising independence: therefore not a line in these pages has been written by any but degreeless students or young graduates. It has been our object to gather all and none but the not yet ripe fruits of art, science and philosophy in the university. We did not wish so much that our articles should be sober and guarded as that they should be stimulating and lively and take up a strong line. We were prepared in fact to give ourselves away. But we know that Cambridge is painfully well-balanced just now (a sign, perhaps of anxiety neurosis) and so we were prepared also to find, as the reader will find, rather too guarded and sensible a daring. Perhaps we will ripen into extravagance. Contributions for the second number should be send to W. Empson of Magdalene College. We five are acting on behalf of the contributors, who have entrusted us with this part of the work. -

March 18, 2014

March 18, 2014 Student Highlight Faculty Updates Mazal Collection in the News Russian-A merican Journalist & A ctivist Masha Gessen Comes to CU East European Jewish A ffairs Journal Embodied Judaism Symposium Online Resources and Scholarships for Students On Campus & A round Town Student Highlight... Chelsea is pursuing a minor in Jewish Studies in addition to a major in International Affairs and a certificate in Digital Arts and Media. She first joined the Program in Jewish Studies because she wanted to incorporate genocide and religious studies into her broader major, and was specifically attracted to learning about gendered experiences within both the Holocaust and Judaism. We would like to congratulate Chelsea on recently being awarded the 2014 Jacob Van Ek S cholar Award! An outstanding student, this past year, Chelsea has also received the Wrenn Scholarship from the Boulder Chapter of the United Nations Association and the Ripple Award from the Dennis Small Cultural Center. During her time at CU, Chelsea has served as a member of the Jewish Studies Student Advisory Board, was the co-president of Hillel, played for CU's Women's Rugby team, served on CUSG and Student Outreach Retention Center for Equity (SORCE), and was on the KVCU Radio 1190 Task Force. Chelsea also works for the CU Recreation Center. This past summer 2013, Chelsea completed the CU in D.C. summer session, interning with Women's Action for New Directions and the Women Legislators' Lobby in Washington, DC. She worked particularly on women's advocacy and defense budget issues, as well as nuclear policies. -

The Illusory Distinction Between Equality of Opportunity and Equality of Result

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1992 The Illusory Distinction between Equality of Opportunity and Equality of Result David A. Strauss Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David A. Strauss, "The Illusory Distinction between Equality of Opportunity and Equality of Result," 34 William and Mary Law Review 171 (1992). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ILLUSORY DISTINCTION BETWEEN EQUALITY OF OPPORTUNITY AND EQUALITY OF RESULT DAVID A. STRAUSS* I. INTRODUCTION "Our society should guarantee equality of opportunity, but not equality of result." One hears that refrain or its equivalent with increasing frequency. Usually it is part of a general attack on gov- ernment measures that redistribute wealth, or specifically on af- firmative action, that is, race- and gender-conscious efforts to im- prove the status of minorities and women. The idea appears to be that the government's role is to ensure that everyone starts off from the same point, not that everyone ends up in the same condi- tion. If people have equal opportunities, what they make of those opportunities is their responsibility. If they end up worse off, the government should not intervene to help them.1 In this Article, I challenge the usefulness of the distinction be- tween equality of opportunity and equality of result. -

Curtailing Inherited Wealth

Michigan Law Review Volume 89 Issue 1 1990 Curtailing Inherited Wealth Mark L. Ascher University of Arizona College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Law and Society Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Taxation-Federal Estate and Gift Commons Recommended Citation Mark L. Ascher, Curtailing Inherited Wealth, 89 MICH. L. REV. 69 (1990). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol89/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CURTAILING INHERITED WEALTH Mark L. Ascher* INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • • • • . • • • • • • • • . • • . • • • • . • • • 70 I. INHERITANCE IN PRINCIPLE........................... 76 A. Inheritance as a Natural Right..................... 76 B. The Positivistic Conception of Inheritance . 77 C. Why the Positivistic Conception Prevailed . 78 D. Inheritance - Property or Garbage?................ 81 E. Constitutional Concerns . 84 II. INHERITANCE AS A MATIER OF POLICY •• • . •••••.. •••• 86 A. Society's Stake in Accumulated Wealth . 86 B. Arguments in Favor of Curtailing Inheritance . 87 1. Leveling the Playing Field . 87 2. Deficit Reduction in a Painless and Appropriate Fashion........................................ 91 3. Protecting Elective Representative Government . 93 4. Increasing Privatization in the Care of the Disabled and the Elderly . 96 5. Expanding Public Ownership of National and International Treasures . 98 6. _Increasing Lifetime Charitable Giving . 98 7. Neutralizing the Co"osive Effects of Wealth..... 99 C. Arguments Against Curtailing Inheritance. -

The Youth's Instructor for 1957

Maryane Myers pictures in miniature the misery that comes with disaster: After Seven Years—Rain JULY 23, 1957 Bible Lesson for August 3 it ° WE HOLD THESE TRUTHS Are You a Berean? THE YOUTH'S INSTRUCTOR is read by many who COVER We are indebted to the Dallas do not necessarily accept the teachings and practices of its Morning News for the picture of a boy on Seventh-day Adventist publishers. It is to such readers that our our cover. He is smiling through a not-so- question is addressed—Are you a Berean? happy situation for many people. For a Tenor There is nothing mysterious about either the query or the of Our Times article turn to Maryane Myers' center-spread report, "After Seven Years— name it employs. Reference is made to the Bereans in the Scrip- Rain." A single article can give only a keyhole ture lesson beginning on page 17. Of them it was written: "These view of the disaster that has followed what were more noble than those in Thessalonica, in that they received the Weekly Reader of January 7-11, 1957, the word with all readiness of mind, and searched the scriptures credited scientists as saying was the worst daily, whether those things were so" (Acts 17:11). drought "in 700 years." Why were the residents of Berea judged more noble than the citizens of Thessalonica? Was it an accident of birth? or 23 Tenor of our times articles are item 23 inheritance? or public office? or renown in sports? or victories on our topic-frequency chart. -

Cigarettesaftersex Biog2017 Copy

! ! BIOGRAPHY 2017 ! ! On August 18th 2017, Ghostpoet aka Obaro Ejimiwe returns with his eagerly anticipated fourth album. As the title suggests, Dark Days & Canapés is a record that siphons the sense of unease hanging in the air throughout the time of its creation and uses it as a fuel source. It’s also a record that dramatically fore- grounds the continuing evolution of twice- Mercury nominated Obaro as one of our most perspicacious and original songwriters. In the wake of 2015’s universally acclaimed Shedding Skin – an album which found him moving away from the beats-driven arrangements of the first two records – Dark Days & Canapés completes the transition to a fuller band sound. Integral to that transition was Obaro’s choice of producer for the record. “On previous records, the production side of things has run along 50:50 lines,” he explains, “But this time around, I wanted to see what would happen if I relaxed that a little.” Early in the process, he hooked up with producer/writer/ guitarist Leo Abrahams, perhaps best known for his work with Brian Eno and Jon Hopkins (Small Craft On A Milk Sea) and Wild Beasts (Present Tense) as well as his own feted solo albums. The two clicked immediately. “I went to his studio in East London,” recalls Obaro, “And the thing that struck me about him was that he was impossible to faze. I was de- scribing the mood I was after in quite fanciful, surreal terms, and yet he knew exactly how to translate !that into music.” The results of those early sessions - which saw guitarist Joe Newman assisting, fleshing out guitar parts on the early demos -quickly established the momentum of what followed. -

Autocracy: Rules for Survival | by Masha Gessen | NYR Daily

Autocracy: Rules for Survival Masha Gessen “Thank you, my friends. Thank you. Thank you. We have lost. We have lost, and this is the last day of my political career, so I will say what must be said. We are standing at the edge of the abyss. Our political system, our society, our country itself are in greater danger than at any time in the last century and a half. The president-elect has made his intentions clear, and it would be immoral to pretend otherwise. We must band together right now to defend the laws, the institutions, and the ideals on which our country is based.” That, or something like that, is what Hillary Clinton should have said on Wednesday. Instead, she said, resignedly, We must accept this result and then look to the future. Donald Trump is going to be our president. We owe him an open mind and the chance to lead. Our constitutional democracy enshrines the peaceful transfer of power. We don’t just respect that. We cherish it. It also enshrines the rule of law; the principle [that] we are all equal in rights and dignity; freedom of worship and expression. We respect and cherish these values, too, and we must defend them. Hours later, President Barack Obama was even more conciliatory: We are now all rooting for his success in uniting and leading the country. The peaceful transition of power is one of the hallmarks of our democracy. And over the next few months, we are going to show that to the world….We have to remember that we’re actually all on one team. -

Russia: Background and U.S

Russia: Background and U.S. Policy Updated August 21, 2017 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44775 Russia: Background and U.S. Policy Summary Over the last five years, Congress and the executive branch have closely monitored and responded to new developments in Russian policy. These developments include the following: increasingly authoritarian governance since Vladimir Putin’s return to the presidential post in 2012; Russia’s 2014 annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea region and support of separatists in eastern Ukraine; violations of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty; Moscow’s intervention in Syria in support of Bashar al Asad’s government; increased military activity in Europe; and cyber-related influence operations that, according to the U.S. intelligence community, have targeted the 2016 U.S. presidential election and countries in Europe. In response, the United States has imposed economic and diplomatic sanctions related to Russia’s actions in Ukraine and Syria, malicious cyber activity, and human rights violations. The United States also has led NATO in developing a new military posture in Central and Eastern Europe designed to reassure allies and deter aggression. U.S. policymakers over the years have identified areas in which U.S. and Russian interests are or could be compatible. The United States and Russia have cooperated successfully on issues such as nuclear arms control and nonproliferation, support for military operations in Afghanistan, the Iranian and North Korean nuclear programs, the International Space Station, and the removal of chemical weapons from Syria. In addition, the United States and Russia have identified other areas of cooperation, such as countering terrorism, illicit narcotics, and piracy. -

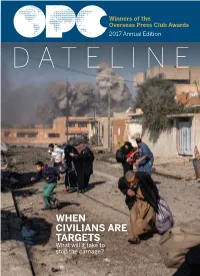

WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What Will It Take to Stop the Carnage?

Winners of the Overseas Press Club Awards 2017 Annual Edition DATELINE WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What will it take to stop the carnage? DATELINE 2017 1 President’s Letter / dEIdRE dEPkE here is a theme to our gathering tonight at the 78th entries, narrowing them to our 22 winners. Our judging process was annual Overseas Press Club Gala, and it’s not an easy one. ably led by Scott Kraft of the Los Our work as journalists across the globe is under Angeles Times. Sarah Lubman headed our din- unprecedented and frightening attack. Since the conflict in ner committee, setting new records TSyria began in 2011, 107 journalists there have been killed, according the for participation. She was support- Committee to Protect Journalists. That’s more members of the press corps ed by Bill Holstein, past president of the OPC and current head of to die than were lost during 20 years of war in Vietnam. In the past year, the OPC Foundation’s board, and our colleagues also have been fatally targeted in Iraq, Yemen and Ukraine. assisted by her Brunswick colleague Beatriz Garcia. Since 2013, the Islamic State has captured or killed 11 journalists. Almost This outstanding issue of Date- 300 reporters, editors and photographers are being illegally detained by line was edited by Michael Serrill, a past president of the OPC. Vera governments around the world, with at least 81 journalists imprisoned Naughton is the designer (she also in Turkey alone. And at home, we have been labeled the “enemy of the recently updated the OPC logo). -

Honoring the Recent Fallen Lt

OCTOBER 27, 2016 1 THE OCTOBER 27, 2016 VOL. 73, NO. 42 ® UTY ONOR OUNTRY OINTER IEW D , H , C PSERVING THE U.S. MILITARY ACADEMY AND THE COMMUNITY V OF WEST POINT ® Honoring the recent Fallen Lt. Gen. Robert L. Caslen Jr., superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy, leads the Army West Point Football team into Michie Stadium on a motorcycle donated by the father of fallen Cadet Thomas Surdyke, Oct. 22 at West Point. The custom bike commemorates three cadets (Surdyke, Mitch Winey and Brandon Jackson) and two recent graduates (2nd Lts. Mike Parros and Andrew Hunt) who have passed away this year. PHOTO BY MAJ. SCOT KEITH/USMA PAO INSIDE & #USMA Social Scene SEE PAGE 3— ONLINE SEE PAGE 12 FAMILY WEEKEND WWW . USMA . EDU WWW . POINTERVIEW . COM 2 OCTOBER 27, 2016 NEWS & FEATURES POINTER VIEW Army Football game day security message to community By Col. Andrew Hanson or after 5 p.m. game day. USAG-West Point Garrison Commander If you do stay on West Point, walking or using the game day shuttle buses to and from areas on West Point is highly Ensuring the protection of our Soldiers, Cadets, family encouraged. members and Civilian employees is the priority at West Road closures on game day: Point. 1.) Starting at 6 a.m., Mills Road, from Herbert Hall to Army Football home games pose certain challenges for Stony Lonesome Road, will be closed. Only those vehicles everyone on West Point and we want to ensure our garrison with a proper vehicle exception pass, or under Military and community know of our game day force protection Police escort are allowed access around Michie Stadium. -

Mourning the Family Album

Mourning the Family Album Tahneer Oksman a/b: Auto/Biography Studies, Volume 24, Number 2, Winter 2009, pp. 235-248 (Article) Published by The Autobiography Society DOI: 10.1353/abs.2010.0002 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/abs/summary/v024/24.2.oksman.html Access Provided by New York University at 08/17/12 1:24AM GMT Mourning the Family Album By Tahneer Oksman The oval portrait of a dog was me at an early age. Something shimmers, something is hushed up —John Ashbery, “This Room” ANY MEMOIRS begin with youth—not just as a convenient mode Mof organization, but because the early years represent a kind of clean slate of consciousness, a time before the full range of pos- sibilities for self-reflection can be realized. As literal relics of the past, photographs are especially interesting objects to use to think about the past idyllic image of a self, the image that is forever being held up against the present self. In Jo Spence’s photographic memoir Putting Myself in the Picture, for instance, there is a photograph of the face of a six-year-old smiling girl with light hair and short bangs. The note beneath the photo reads, “Six years: looking like an uncared for, but rather cheeky ‘orphan’. This is a ‘face’ I still see on me even now. Less often though” (86). However much Spence has moved away from this photograph both in time (as an adult) and in percep- tion (as a photographer who examines and destabilizes the idea of a fixed image/identity), she is still trapped within its frame.