Environmental Assessment for Infrastructure Within U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trip Report for Travel to Arizona the Week of January 23 , 2006

Trip Report for Travel to Arizona the Week of January 23rd, 2006. William B. Reed, Senior Hydrologist, NOAA’s NWS Colorado Basin River Forecast Center Itinerary: Traveled to Tucson on Monday, January 23, 2006; and returned from Tucson to Salt Lake City on Friday January 27, 2006. During the week I was accompanied by Michael Schaffner, Service Hydrologist, Tucson. Mike prearranged field logistics (including the borrowing of survey equipment) that provided for a very productive and conducive trip. Monday night – Tucson Tuesday night – Tucson Wednesday night – Safford Thursday night – Safford Part of Tuesday, Mike and I were joined by Elise Moore, County Floodplain Manager, Pinal County Department of Public Works, P.O. Box 727, Florence, AZ 85232. Noon Creek. Photo by Mike Schaffner (January 2006). Purpose: To visit river forecast points, meet with hydrologic customers, evaluate flood hazards at locations removed from stream gages, and collect hydrologic data related to recent burn-area peak flows. The later will be included in a peer-review journal article that Bill and Mike are completing related to post-burn runoff. (See picture previous page: Bill Reed measuring depth of peak flow water surface with survey rod. A tape measure has been stretched across the channel to correspond to the water surface at time of peak flow. Noon Creek is a 3 square mile watershed in the Pinaleno Mountains of Graham County. Water encompassed a cross sectional area 110 feet wide and a minimum of 10.5 feet deep at the time of peak flow to yield a peak flow in excess of 2,500 cfs.) Accomplishments: Monday: Madera Canyon. -

Friends of the San Pedro River Roundup

Friends of the San Pedro River Roundup Winter 2014 In This Issue: Bioblitz... Lectures... Film Festival... Executive Director’s Report... Festival of Arts... BLM Acting Director’s Visit... Archeology & Heritage Month... Dark Skies Position... Ron Beck’s Big Year... Christmas Bird Count Results... Trees along the 19th-Century River... Brunckow’s Cabin Rehab... EOP Leaders Sought... Walkway Bricks... Operations Committee... Members ... Calendar ... Contacts Save the Date! The morning of April 26, FSPR will hold a Bioblitz (an inventory of the flora and fauna) at various locations in SPRNCA. Stay tuned for details in the coming weeks. FSPR Lectures February & March 20 JoinPawlowski, us on Thursday, Water Sentinels February Program 20 at 7 Coordinatorpm at the Sierra for the Vista Grand Ranger Canyon District Chapter Office, of 4070the Sierra East AvenidaClub, will Saracino, Hereford, for a lecture by Becky Orozco on the Chiracahua Apache. Then, on March 20, Steve discuss ecology and conservation of the San Pedro River; current threats; and the conservation work of the Sentinels within SPRNCA. Learn how to use citizen science, “hands-on” conservation, and advocacy to shape a more-sustainable future for one of the Southwest’s most ecologically significant rivers. Second Annual Wild & Scenic Film Festival March 13 & 14 The Friends have been invited to host our second Wild & Scenic Film Festival as part of the 12th annual event that showcases North America’s premier collection of short films on the environment. We have selected 13 films for the evening program for adults that are relevant to many of the issues facing the Southwest. Some will make you smile, some may get you angry, others will have you amazed, but hopefully, all will motivate you to get involved. -

Notices of Public Information 3489

Arizona Administrative Register Notices of Public Information NOTICES OF PUBLIC INFORMATION Notices of Public Information contain corrections that agencies wish to make to their notices of rulemaking; miscella- neous rulemaking information that does not fit into any other category of notice; and other types of information required by statute to be published in the Register. Because of the variety of material that is contained in a Notice of Public Information, the Office of the Secretary of State has not established a specific format for these notices. NOTICE OF PUBLIC INFORMATION DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY 1. A.R.S. Title and its heading: 49, The Environment A.R.S. Chapter and its heading: 2, Water Quality Control A.R.S. Article and its heading: 2.1, Total Maximum Daily Loads A.R.S. Sections: A.R.S. § 49-232, Lists of Impaired Waters; Data Requirements; Rules 2. The public information relating to the listed statute: A.R.S. § 49-232(A) requires the Department to at least once every five years, prepare a list of impaired waters for the pur- pose of complying with section 303(d) of the Clean Water Act (33 U.S.C. 1313(d)). The Department shall provide public notice and allow for comment on a draft list of impaired waters prior to its submission to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The Department shall prepare written responses to comments received on the draft list. The Department shall publish the list of impaired waters that it plans to submit initially to the regional administrator and a summary of the responses to comments on the draft list in the Arizona Administrative Register at least forty-five days before submission of the list to the regional administrator. -

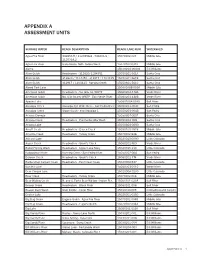

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

TMDL Deposition Document Abandoned Mines Boulder Creek - Arsenic the Final TMDL TMDL Document Hillside Mine 7/26/04 Part 1: J

Arizona's Total Maximum Daily Load Program - History and Current Status as of 11/14/11 Bill Williams Watershed Colorado River/Grand Canyon Watershed Colorado River/Lower Gila River Watershed Little Colorado River Watershed Middle Gila Watershed Salt River Watershed San Pedro Watershed Santa Cruz River Watershed Verde River Watershed Upper Gila Watershed Bill Williams Watershed Impaired Water Pollutant(s) Status Downloadable Types of Approved Implementation Staff Covered Information Point/ by EPA Plans/Activities Contact Nonpoint Name Sources Alamo Lake Mercury Updating Model. Fact Sheet Atmospheric No No S. Fitch Draft Mercury TMDL deposition Document Abandoned mines Boulder Creek - Arsenic The final TMDL TMDL Document Hillside Mine 7/26/04 Part 1: J. Wilder Creek to report has been (abandoned), Characterization Sutter Copper Copper Creek completed. remnant Part 2: Zinc tailings piles Implementation Plan Colorado River/Grand Canyon Watershed Impaired Water Pollutant(s) Status Downloadable Types of Approved Implementation Staff Covered Information Point/ by EPA Plans/Activities Contact Nonpoint Name Sources No past or current projects in this watershed Colorado River/Lower Watershed Impaired Water Pollutant(s) Status Downloadable Types of Approved Implementation Staff Covered Information Point/ by EPA Plans/Activities Contact Nonpoint Name Sources Lower Colorado Nitrogen The final TMDL TMDL Document 1992 No J. River - Yuma USGS report has been Sutter Phosphorus Gage 0952110 to completed. International Border Little Colorado River Watershed Impaired Water Pollutant(s) Status Downloadable Types of Approved Implementation Staff Covered Information Point/ by EPA Plans/Activities Contact Nonpoint Name Sources Lake Mary (lower) Mercury Updating model Fact Sheet Under No No S. Fitch and draft TMDL. -

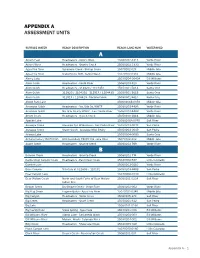

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED A Ackers East Headwaters - Ackers West 15060202-3313 Verde River Ackers West Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-3333 Verde River Agua Fria River Sycamore Creek - Bishop Creek 15070102-023 Middle Gila Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo Lake 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alder Creek Headwaters - Verde River 15060203-910 Verde River Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820 / 1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - Aravaipa Wild. Bndry 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arizona Canal (15070102) HUC boundary 15070102 - Gila River 15070102-202 Middle Gila Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River B Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bass Canyon Tributary at 322606 / 110131 15050203-899B San Pedro -

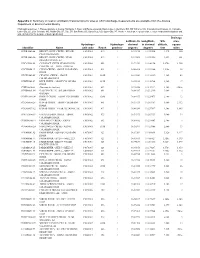

USGS Open-File Report 2009-1269, Appendix 2

Appendix 2. Summary of location and basin characteristics for sites at which discharge measurements are available from the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality [Hydrologic provinces: 1, Plateau Uplands; 2, Central Highlands; 3, Basin and Range Lowlands. Basin codes in Identifiers: BW, Bill Williams; CG, Colorado-Grand Canyon; Cl, Colorado- Lower Gila; LC, Little Colorado; MG, Middle Gila; SR, Salt; SP, San Pedro; SC, Santa Cruz; UG, Upper Gila; VR, Verde. <, less than; >, greater than; e, value not present in database and was estimated for the purpose of model predictions] Drainage Latitude, in Longitude, Site area, Hydrologic Hydrologic decimal in decimal altitude, square Identifier Name unit code Reach province degrees degrees feet miles CGBRA000.44 BRIGHT ANGEL CREEK - BELOW 15010001 019 1 36.10236 112.09514 2,520 100 PHANTOM RANCH CGBRA000.50 BRIGHT ANGEL CREEK - NEAR 15010001 019 1 36.10306 112.09556 2,452 101 GRAND CANYON, AZ CGCAT056.68 CATARACT CREEK NEAR GRAND 15010004 005 1 35.72333 112.44194 5,470e 1,200 CANYON, AZ USGS 09404100 CGCLE000.19 CLEAR CREEK - ABOVE COLORADO 15010001 025 1 36.08414 112.03344 2,520e 36 RIVER CGCRY000.05 CRYSTAL CREEK - ABOVE 15010002 018B 1 36.13542 112.24319 2,360 43 COLORADO RIVER CGDEE000.07 DEER CREEK - ABOVE COLORADO 15010002 019B 1 36.38931 112.50764 1,960 17 RIVER CGDIA000.06 (No name in database) 15010002 002 1 35.76556 113.37222 1,340 <946e CGGDN001.09 GARGEN CREEK - BELOW INDIAN 15010002 841 1 36.08347 112.12319 3,600 4 GARDEN CGHRM000.08 HERMIT CREEK - ABOVE COLORADO 15010002 020B -

San Pedro Valley, Arizona

An exploration gravity survey in the San Pedro Valley, southeastern Arizona Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic); maps Authors Halvorson, Phyllis Heather Fett Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 12:54:48 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/557989 AN EXPLORATION GRAVITY SURVEY IN THE SAN PEDRO VALLEY, SOUTHEASTERN ARIZONA b y Phyllis Heather Fett Halverson A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF GEOSCIENCES In Partial Fullfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE WITH A MAJOR IN GEOPHYSICS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 8 4 — r I i ,, >——» OQ a Call No. BINDING INSTRUCTIONS INSTRUCTIONS INTERUBRARY STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of require ments for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotations from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate School when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

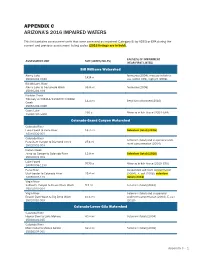

Appendix C Arizona's 2016 Impaired Waters

APPENDIX C ARIZONA’S 2016 IMPAIRED WATERS This list contains assessment units that were assessed as impaired (Category 5) by ADEQ or EPA during the current and previous assessment listing cycles (2016 listings are in bold). CAUSE(S) OF IMPAIRMENT ASSESSMENT UNIT SIZE (ACRES/MILES) (YEAR FIRST LISTED) Bill Williams Watershed Alamo Lake Ammonia (2004), mercury in fish tis- 1414 a 15030204-0040 sue (2002- EPA), high pH (1996) Bill Williams River Alamo Lake to Castaneda Wash 35.9 mi Ammonia (2006) 15030204-003 Boulder Creek Tributary at 344114/1131800 to Wilder 14.4 mi Beryllium (dissolved)(2010) Creek 15030202-006B Coors Lake 230 a Mercury in fish tissue (2004- EPA) 15030202-5000 Colorado-Grand Canyon Watershed Colorado River Lake Powell to Paria River 16.3 mi Selenium (total) (2016) 14070006-001 Colorado River Selenium (total) and suspended sedi- Parashant Canyon to Diamond Creek 27.6 mi ment concentration (2004) 15010002-003 Kanab Creek Jump-up Canyon to Colorado River 12.8 m Selenium (total) (2016) 15010003-001 Lake Powell 9770 a Mercury in fish tissue (2010- EPA) 14070006-1130 Paria River Suspended sediment concentration Utah border to Colorado River 29.4 mi (2004), E. coli (2006), selenium 14070007-123 (total) (2016) Virgin River Sullivan’s Canyon to Beaver Dam Wash 9.7 mi Selenium (total) (2012) 15010010-004 Virgin River Selenium (total) and suspended Beaver Dam Wash to Big Bend Wash 10.1 mi sediment concentration (2004), E. coli 15010010-003 (2010) Colorado-Lower Gila Watershed Colorado River Hoover Dam to Lake Mohave 40.4 mi Selenium -

The Development of Piping Erosion

The development of piping erosion Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic); maps Authors Jones, Neil Owen Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 12:01:34 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/565170 THE DEVELOPMENT OF PIPING EROSION Neil Owen Jones, Ph. D. The University of Arizona, 1968 Director: Lawrence K. Lustlg Piping erosion is widespread in the semiarid valleys of the southwestern United States. The extensive pipe sys tems near Benson in the San Pedro Valley, Arizona, were studied to determine the prerequisite conditions for piping, factors affecting pipe evolution and the effect of piping on subsequent development of the drainage net. It is believed that extensive piping was initiated after arroyo-cuttlng began in the San Pedro Valley about 1890. Since that time slightly less than 10 percent of the Aravalpa Surface has been affected by piping, but the af fected area includes some 40 percent of the cultivated land, most of which is adjacent to the river. Field studies in cluded determination of the geomorphic and hydrologic set ting of the major pipe systems and detailed mapping of rep resentative pipe systems to determine the influence of local geologic structures on piping. Changes in a representative pipe system during the study period were measured. Se quences of aerial photographs for the period 1935-66 indicate the long-term rate of development of pipe systems and their relation to the drainage net. -

Section VII Potential Linkage Zones SECTION VII POTENTIAL LINKAGE ZONES

2006 ARIZONA’S WILDLIFE LINKAGES ASSESSMENT 41 Section VII Potential Linkage Zones SECTION VII POTENTIAL LINKAGE ZONES Linkage 1 Linkage 2 Beaver Dam Slope – Virgin Slope Beaver Dam – Virgin Mountains Mohave Desert Ecoregion Mohave Desert Ecoregion County: Mohave (Linkage 1: Identified Species continued) County: Mohave Kit Fox Vulpes macrotis ADOT Engineering District: Flagstaff and Kingman Mohave Desert Tortoise Gopherus agassizii ADOT Engineering District: Flagstaff ADOT Maintenance: Fredonia and Kingman Mountain Lion Felis concolor ADOT Maintenance: Fredonia ADOT Natural Resources Management Section: Flagstaff Mule Deer Odocoileus hemionus ADOT Natural Resources Management Section: Flagstaff Speckled Dace Rhinichthys osculus Spotted Bat Euderma maculatum AGFD: Region II AGFD: Region II Virgin Chub Gila seminuda Virgin Spinedace Lepidomeda mollispinis mollispinis BLM: Arizona Strip District Woundfin Plagopterus argentissimus BLM: Arizona Strip District Congressional District: 2 Threats: Congressional District: 2 Highway (I 15) Council of Government: Western Arizona Council of Governments Urbanization Council of Government: Western Arizona Council of Governments FHWA Engineering: A2 and A4 Hydrology: FHWA Engineering: A2 Big Bend Wash Legislative District: 3 Coon Creek Legislative District: 3 Virgin River Biotic Communities (Vegetation Types): Biotic Communities (Vegetation Types): Mohave Desertscrub 100% Mohave Desertscrub 100% Land Ownership: Land Ownership: Bureau of Land Management 59% Bureau of Land Management 93% Private 27% Private -

ADMMR Mining Collection Inventory

ADMMR MINING COLLECTION INVENTORY Casey Brown Arizona Geological Survey OPEN-FILE REPORT OFR-12-37 September 2012 Arizona Geological Survey www.azgs.az.gov | repository.azgs.az.gov Arizona Geological Survey M. Lee Allison, State Geologist and Director Manuscript approved for publication in September 2012 Printed by the Arizona Geological Survey All rights reserved For an electronic copy of this publication: www.repository.azgs.az.gov Printed copies are on sale at the Arizona Experience Store 416 W. Congress, Tucson, AZ 85701 (520.770.3500) For information on the mission, objectives or geologic products of the Arizona Geological Survey visit www.azgs.az.gov. This publication was prepared by an agency of the State of Arizona. The State of Arizona, or any agency thereof, or any of their employees, makes no warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed in this report. Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the State of Arizona. ___________________________ Recommended Citation: Brown, C., 2012, ADMMR mining collection. Arizona Geological Survey Open File Report, OFR-12-37, 152 p. ADMMR mining collection by Casey Brown Arizona Geological Survey Open-File Report 12-37 August 2012 Curating and documenting this collection was supported by the State of Arizona and the U.S. Geological Survey National Geological and Geophysical Data Preservation Program Grant #G11AP20180. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S.