The Dark Ecology of William Gibson's Neuromancer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyberpunking a Library

Cyberpunking a Library Collection assessment and collection Leanna Jantzi, Neil MacDonald, Samantha Sinanan LIBR 580 Instructor: Simon Neame April 8, 2010 “A year here and he still dreamed of cyberspace, hope fading nightly. All the speed he took, all the turns he’d taken and the corners he’d cut in Night City, and he’d still see the matrix in his sleep, bright lattices of logic unfolding across that colorless void.” – Neuromancer, William Gibson 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Description of Subject ....................................................................................................................................... 3 History of Cyberpunk .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Themes and Common Motifs....................................................................................................................................... 3 Key subject headings and Call number range ....................................................................................................... 4 Description of Library and Community ..................................................................................................... -

A Very Short History of Cyberpunk

A Very Short History of Cyberpunk Marcus Janni Pivato Many people seem to think that William Gibson invented The cyberpunk genre in 1984, but in fact the cyberpunk aesthetic was alive well before Neuromancer (1984). For example, in my opinion, Ridley Scott's 1982 movie, Blade Runner, captures the quintessence of the cyberpunk aesthetic: a juxtaposition of high technology with social decay as a troubling allegory of the relationship between humanity and machines ---in particular, artificially intelligent machines. I believe the aesthetic of the movie originates from Scott's own vision, because I didn't really find it in the Philip K. Dick's novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (1968), upon which the movie is (very loosely) based. Neuromancer made a big splash not because it was the "first" cyberpunk novel, but rather, because it perfectly captured the Zeitgeist of anxiety and wonder that prevailed at the dawning of the present era of globalized economics, digital telecommunications, and exponential technological progress --things which we now take for granted but which, in the early 1980s were still new and frightening. For example, Gibson's novels exhibit a fascination with the "Japanification" of Western culture --then a major concern, but now a forgotten and laughable anxiety. This is also visible in the futuristic Los Angeles of Scott’s Blade Runner. Another early cyberpunk author is K.W. Jeter, whose imaginative and disturbing novels Dr. Adder (1984) and The Glass Hammer (1985) exemplify the dark underside of the genre. Some people also identify Rudy Rucker and Bruce Sterling as progenitors of cyberpunk. -

New Alt.Cyberpunk FAQ

New alt.cyberpunk FAQ Frank April 1998 This is version 4 of the alt.cyberpunk FAQ. Although previous FAQs have not been allocated version numbers, due the number of people now involved, I've taken the liberty to do so. Previous maintainers / editors and version numbers are given below : - Version 3: Erich Schneider - Version 2: Tim Oerting - Version 1: Andy Hawks I would also like to recognise and express my thanks to Jer and Stack for all their help and assistance in compiling this version of the FAQ. The vast number of the "answers" here should be prefixed with an "in my opinion". It would be ridiculous for me to claim to be an ultimate Cyberpunk authority. Contents 1. What is Cyberpunk, the Literary Movement ? 2. What is Cyberpunk, the Subculture ? 3. What is Cyberspace ? 4. Cyberpunk Literature 5. Magazines About Cyberpunk and Related Topics 6. Cyberpunk in Visual Media (Movies and TV) 7. Blade Runner 8. Cyberpunk Music / Dress / Aftershave 9. What is "PGP" ? 10. Agrippa : What and Where, is it ? 1. What is Cyberpunk, the Literary Movement ? Gardner Dozois, one of the editors of Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine during the early '80s, is generally acknowledged as the first person to popularize the term "Cyberpunk", when describing a body of literature. Dozois doesn't claim to have coined the term; he says he picked it up "on the street somewhere". It is probably no coincidence that Bruce Bethke wrote a short story titled "Cyberpunk" in 1980 and submitted it Asimov's mag, when Dozois may have been doing first readings, and got it published in Amazing in 1983, when Dozois was editor of1983 Year's Best SF and would be expected to be reading the major SF magazines. -

The Disappearing Human: Gnostic Dreams in a Transhumanist World

religions Article The Disappearing Human: Gnostic Dreams in a Transhumanist World Jeffrey C. Pugh Department of Religious Studies, Elon University, Elon, NC 27244-2020, USA; [email protected] Academic Editor: Noreen Herzfeld Received: 25 January 2017; Accepted: 18 April 2017; Published: 3 May 2017 Abstract: Transhumanism is dedicated to freeing humankind from the limitations of biological life, creating new bodies that will carry us into the future. In seeking freedom from the constraints of nature, it resembles ancient Gnosticism, but complicates the question of what the human being is. In contrast to the perspective that we are our brains, I argue that human consciousness and subjectivity originate from complex interactions between the body and the surrounding environment. These qualities emerge from a distinct set of structural couplings embodied within multiple organ systems and the multiplicity of connections within the brain. These connections take on different forms, including structural, chemical, and electrical manifestations within the totality of the human body. This embodiment suggests that human consciousness, and the intricate levels of experience that accompany it, cannot be replicated in non-organic forms such as computers or synaptic implants without a significant loss to human identity. The Gnostic desire to escape our embodiment found in transhumanism carries the danger of dissolving the human being. Keywords: Singularity; transhumanism; Merleau-Ponty; Kurzweil; Gnosticism; AI; emergence; technology 1. Introduction In 1993, the mathematician and science fiction writer Vernor Vinge gave a talk at the Vision 21 symposium sponsored by NASA introducing the idea of the Singularity, an evolutionary moment when we would create the capacity for superhuman intelligence that would transcend the human and take us into the posthuman world (Vinge 1993). -

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century Carlen Lavigne McGill University, Montréal Department of Art History and Communication Studies February 2008 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies © Carlen Lavigne 2008 2 Abstract This study analyzes works of cyberpunk literature written between 1981 and 2005, and positions women’s cyberpunk as part of a larger cultural discussion of feminist issues. It traces the origins of the genre, reviews critical reactions, and subsequently outlines the ways in which women’s cyberpunk altered genre conventions in order to advance specifically feminist points of view. Novels are examined within their historical contexts; their content is compared to broader trends and controversies within contemporary feminism, and their themes are revealed to be visible reflections of feminist discourse at the end of the twentieth century. The study will ultimately make a case for the treatment of feminist cyberpunk as a unique vehicle for the examination of contemporary women’s issues, and for the analysis of feminist science fiction as a complex source of political ideas. Cette étude fait l’analyse d’ouvrages de littérature cyberpunk écrits entre 1981 et 2005, et situe la littérature féminine cyberpunk dans le contexte d’une discussion culturelle plus vaste des questions féministes. Elle établit les origines du genre, analyse les réactions culturelles et, par la suite, donne un aperçu des différentes manières dont la littérature féminine cyberpunk a transformé les usages du genre afin de promouvoir en particulier le point de vue féministe. -

Information Age Anthology Vol II

DoD C4ISR Cooperative Research Program ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF DEFENSE (C3I) Mr. Arthur L. Money SPECIAL ASSISTANT TO THE ASD(C3I) & DIRECTOR, RESEARCH AND STRATEGIC PLANNING Dr. David S. Alberts Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Defense, or any other U.S. Government agency. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Portions of this publication may be quoted or reprinted without further permission, with credit to the DoD C4ISR Cooperative Research Program, Washington, D.C. Courtesy copies of reviews would be appreciated. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Alberts, David S. (David Stephen), 1942- Volume II of Information Age Anthology: National Security Implications of the Information Age David S. Alberts, Daniel S. Papp p. cm. -- (CCRP publication series) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-893723-02-X 97-194630 CIP August 2000 VOLUME II INFORMATION AGE ANTHOLOGY: National Security Implications of the Information Age EDITED BY DAVID S. ALBERTS DANIEL S. PAPP TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ................................................ v Preface ................................................................ vii Chapter 1—National Security in the Information Age: Setting the Stage—Daniel S. Papp and David S. Alberts .................................................... 1 Part One Introduction......................................... 55 Chapter 2—Bits, Bytes, and Diplomacy—Walter B. Wriston ................................................................ 61 Chapter 3—Seven Types of Information Warfare—Martin C. Libicki ................................. 77 Chapter 4—America’s Information Edge— Joseph S. Nye, Jr. and William A. Owens....... 115 Chapter 5—The Internet and National Security: Emerging Issues—David Halperin .................. 137 Chapter 6—Technology, Intelligence, and the Information Stream: The Executive Branch and National Security Decision Making— Loch K. -

The Virtual Worlds of Japanese Cyberpunk

arts Article New Spaces for Old Motifs? The Virtual Worlds of Japanese Cyberpunk Denis Taillandier College of International Relations, Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto 603-8577, Japan; aelfi[email protected] Received: 3 July 2018; Accepted: 2 October 2018; Published: 5 October 2018 Abstract: North-American cyberpunk’s recurrent use of high-tech Japan as “the default setting for the future,” has generated a Japonism reframed in technological terms. While the renewed representations of techno-Orientalism have received scholarly attention, little has been said about literary Japanese science fiction. This paper attempts to discuss the transnational construction of Japanese cyberpunk through Masaki Goro’s¯ Venus City (V¯ınasu Shiti, 1992) and Tobi Hirotaka’s Angels of the Forsaken Garden series (Haien no tenshi, 2002–). Elaborating on Tatsumi’s concept of synchronicity, it focuses on the intertextual dynamics that underlie the shaping of those texts to shed light on Japanese cyberpunk’s (dis)connections to techno-Orientalism as well as on the relationships between literary works, virtual worlds and reality. Keywords: Japanese science fiction; cyberpunk; techno-Orientalism; Masaki Goro;¯ Tobi Hirotaka; virtual worlds; intertextuality 1. Introduction: Cyberpunk and Techno-Orientalism While the inversion is not a very original one, looking into Japanese cyberpunk in a transnational context first calls for a brief dive into cyberpunk Japan. Anglo-American pioneers of the genre, quite evidently William Gibson, but also Pat Cadigan or Bruce Sterling, have extensively used high-tech, hyper-consumerist Japan as a motif or a setting for their works, so that Japan became in the mid 1980s the very exemplification of the future, or to borrow Gibson’s (2001, p. -

"The Infinite Plasticity of the Digital"

"The Infinite Plasticity of the Digital" http://reconstruction.eserver.org/043/leaver.htm Ever since William Gibson coined the term "cyberspace" in his debut novel Neuromancer , his work has been seen by many as a yardstick for postmodern and, more recently, posthuman possibilities. This article critically examines Gibson's second trilogy ( Virtual Light , Idoru and All Tomorrow's Parties ), focusing on the way digital technologies and identity intersect and interact, with particular emphasis on the role of embodiment. Using the work of Donna Haraway, Judith Butler and N. Katherine Hayles, it is argued that while William Gibson's second trilogy is infused with posthuman possibilities, the role of embodiment is not relegated to one choice among many. Rather the specific materiality of individual existence is presented as both desirable and ultimately necessary to a complete existence, even in a posthuman present or future. "The Infinite Plasticity of the Digital": Posthuman Possibilities, Embodiment and Technology in William Gibson's Interstitial Trilogy Tama Leaver Communications technologies and biotechnologies are the crucial tools recrafting our bodies. --- Donna Haraway, "A Cyborg Manifesto" She is a voice, a face, familiar to millions. She is a sea of code ... Her audience knows that she does not walk among them; that she is media, purely. And that is a large part of her appeal. --- William Gibson, All Tomorrow's Parties <1> In the many, varied academic responses to William Gibson's archetypal cyberpunk novel Neuromancer , the most contested site of meaning has been Gibson's re-deployment of the human body. Feminist critic Veronica Hollinger, for example, argued that Gibson's use of cyborg characters championed the "interface of the human and the machine, radically decentring the human body, the sacred icon of the essential self," thereby disrupting the modernist and humanist dichotomy of human and technology, and associated dualisms of nature/culture, mind/body, and thus the gendered binarism of male/female (33). -

Space and the Re-Purposing of Materials and Technology in William Gibson's Neuromancer and Virtual Light Submitted by Grigori

Space and the Re-Purposing of Materials and Technology in William Gibson’s Neuromancer and Virtual Light Submitted by Grigorios Iliopoulos A thesis submitted to the Department of American Literature and Culture, School of English, Faculty of Philosophy of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English and American Studies. Supervisor: Dr. Tatiani Rapatzikou June 2020 Iliopoulos 2 Abstract This thesis explores the relationship between space and technology as well as the re-purposing of tangible and intangible materials in William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984) and Virtual Light (1993). With attention paid to the importance of the cyberpunk setting. Gibson approaches marginal spaces and the re-purposing that takes place in them. The current thesis particularly focuses on spotting the different kinds of re-purposing the two works bring forward ranging from body alterations to artificial spatial structures, so that the link between space and the malleability of materials can be proven more clearly. This sheds light not only on the fusion and intersection of these two elements but also on the visual intensity of Gibson’s writing style that enables readers to view the multiple re-purposings manifested in thε pages of his two novels much more vividly and effectively. Iliopoulos 3 Keywords: William Gibson, cyberspace, utilization of space, marginal spaces, re-purposing, body alteration, technology Iliopoulos 4 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Tatiani Rapatzikou, for all her guidance and valuable suggestions throughout the writing of this thesis. I would also like to express my gratitude to my parents for their unconditional support and understanding. -

Cyberspace Operations

Updated December 15, 2020 Defense Primer: Cyberspace Operations Overview force; (2) compete and deter in cyberspace; (3) strengthen The Department of Defense (DOD) defines cyberspace as a alliances and attract new partnerships; (4) reform the global domain within the information environment department; and (5) cultivate talent. consisting of the interdependent network of information technology infrastructures and resident data, including the Three operational concepts identified in the DOD Cyber internet, telecommunications networks, computer systems, Strategy are to conduct cyberspace operations to collect and embedded processors and controllers. The DOD intelligence and prepare military cyber capabilities to be Information Network (DODIN) is a global infrastructure used in the event of crisis or conflict, and to defend forward carrying DOD, national security, and related intelligence to disrupt or halt malicious cyber activity at its source, community information and intelligence. including activity that falls below the level of armed conflict. Defending forward may involve a more aggressive Cyberspace operations are composed of the military, active defense, meaning activities designed to disrupt an intelligence, and ordinary business operations of the DOD adversary’s network when hostile activity is suspected. in and through cyberspace. Military cyberspace operations use cyberspace capabilities to create effects that support Cyber Mission Force operations across the physical domains and cyberspace. DOD began to build a Cyber Mission Force (CMF) in 2012 Cyberspace operations differ from information operations to carry out DOD’s cyber missions. The CMF consists of (IO), which are specifically concerned with the use of 133 teams that are organized to meet DOD’s three cyber information-related capabilities during military operations missions. -

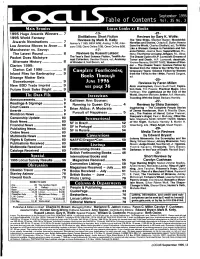

Table of Contents Vol. 35 No. 3

September 1995 Table of Contents vol. 35 no. 3 M a i n S t o r ie s Locus Looks a t Books 1995 Hugo Awards Winners... 7 - 13- - 21 - 1995 World Fantasy Distillations: Short Fiction Reviews by Gary K. Wolfe: Reviews by Mark R. Kelly: The Time Ships, Stephen Baxter; Bloodchild: Awards Nominations .............. 7 Asimov’s 11/95; F&SF 8/95; Analog 11/95; Inter Novellas and Stories, Octavia E. Butler; How to Lou Aronica Moves to Avon.... 8 zone 7/95; Omni Online 7/95; Omni Online 8/95. Save the World, Charles Sheffield, ed.; To Write Like a Woman: Essays in Feminism and Sci Manchester vs. Savoy: - 17- ence Fiction, Joanna Russ; Superstitious, R.L. The Latest Round..................... 8 Reviews by Russell Letson: Stine; The Horror at Camp Jellyjam, R.L. Stine; Pocket Does McIntyre The Year’s Best Science Fiction, Twelfth An The Dream Cycle of H.P. Lovecraft: Dreams of nual Collection, Gardner Dozois, ed ; Anatomy Terror and Death, H.P. Lovecraft; deadrush, Alternate History...................... 8 of Wonder 4, Neil Barron, ed. Yvonne Navarro; SHORT TAKE: Women of Won Clarion 1995; der - The Classic Years: Science Fiction by Women from the 1940s to the 1970s/The Con Clarion Call 1996 .................... 8 C o m p l ete For t hcoming temporary Years: Science Fiction by Women Inland Files for Bankruptcy ...... 9 from the 1970s to the 1990s, Pamela Sargent, Strange Matter Gets Books Thr ough ed. -25- Goosebumps.............................. 9 June 1996 Reviews by Faren Miller: New BDD Trade Imprint ........... 9 See p age 3 6 Alvin Journeyman, Orson Scott Card; Expira Future Book Sales Bright......... -

And the Vestiges of Humanity in William Gibson's

TECHNOLOGICAL DOMINANCE, “DISCARNATE MEN,” AND THE VESTIGES OF HUMANITY IN WILLIAM GIBSON’S NEUROMANCER AND PHILIP K. DICK’S DO ANDROIDS DREAM OF ELECTRIC SHEEP? Robert Sparrow-Downes tba 2020 95 TECHNOLOGICAL DOMINANCE, “DISCARNATE MEN,” AND THE VESTIGES OF HUMANITY IN WILLIAM GIBSON’S NEUROMANCER AND PHILIP K. DICK’S DO ANDROIDS DREAM OF ELECTRIC SHEEP? Robert Sparrow-Downes William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984) tells the story of Case, a “console cowboy” who is unknowingly recruited and manipulated by an artificial intelligence named Wintermute, forced to help the AI break free of its cybernetic constraints and merge with its twin AI, Neuromancer. In having Wintermute and Neuro- mancer merge at the end of the novel, Gibson solidifies artificial intelligence as being the dominant player in the relationship between humans and technology, having now found a way of doing what only humans could do before: self-improve. Case recognizes the dominant position of technology, and his own subordi- nate position, in the novel’s Coda when he asks the newly transformed Wintermute: “So what’s the score? How are things different? You running the world now? You God?”1 As is evident by this quote, and by Case’s reversal of fortune, Gibson provides a stark warning regarding the potential loss of human identity in the modern technological age. Similarly, Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) is set following World War Terminus, a radioactive cataclysmic event responsible for having killed off a significant portion of human and animal life. Following WWT, much of the surviving population has fled to Mars and other planetary colonies in a mass exodus in order to escape the lingering radioactivity; however, as these humans continue to emigrate, some androids (or “replicants”) reverse the course of this exodus and instead arrive on Earth.