Gladiators at Pompeii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Grave Goods of Roman Hierapolis

THE GRAVE GOODS OF ROMAN HIERAPOLIS AN ANALYSIS OF THE FINDS FROM FOUR MULTIPLE BURIAL TOMBS Hallvard Indgjerd Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History University of Oslo This thesis is submitted for the degree of Master of Arts June 2014 The Grave Goods of Roman Hierapolis ABSTRACT The Hellenistic and Roman city of Hierapolis in Phrygia, South-Western Asia Minor, boasts one of the largest necropoleis known from the Roman world. While the grave monuments have seen long-lasting interest, few funerary contexts have been subject to excavation and publication. The present study analyses the artefact finds from four tombs, investigating the context of grave gifts and funerary practices with focus on the Roman imperial period. It considers to what extent the finds influence and reflect varying identities of Hierapolitan individuals over time. Combined, the tombs use cover more than 1500 years, paralleling the life-span of the city itself. Although the material is far too small to give a conclusive view of funerary assem- blages in Hierapolis, the attempted close study and contextual integration of the objects does yield some results with implications for further studies of funerary contexts on the site and in the wider region. The use of standard grave goods items, such as unguentaria, lamps and coins, is found to peak in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. Clay unguentaria were used alongside glass ones more than a century longer than what is usually seen outside of Asia Minor, and this period saw the development of new forms, partially resembling Hellenistic types. Some burials did not include any grave gifts, and none were extraordinarily rich, pointing towards a standardised, minimalistic set of funerary objects. -

Gladiator Politics from Cicero to the White House

Gladiator Politics from Cicero to the White House The gladiator has become a popular icon. He is the hero fighting against the forces of oppression, a Spartacus or a Maximus. He is the "gridiron gladiator" of Monday night football. But he is also the politician on the campaign trail. The casting of the modern politician as gladiator both appropriates and transforms ancient Roman attitudes about gladiators. Ancient gladiators had a certain celebrity, but they were generally identified as infames and antithetical to the behavior and values of Roman citizens. Gladiatorial associations were cast as slurs against one's political opponents. For example, Cicero repeatedly identifies his nemesis P. Clodius Pulcher as a gladiator and accuses him of using gladiators to compel political support in the forum by means of violence and bloodshed in the Pro Sestio. In the 2008 and 2012 presidential campaigns the identification of candidates as gladiators reflects a greater complexity of the gladiator as a modern cultural symbol than is reflected by popular film portrayals and sports references. Obama and Clinton were compared positively to "two gladiators who have been at it, both admired for sticking at it" in their "spectacle" of a debate on February 26, 2008 by Tom Ashbrook and Mike McIntyre on NPR's On Point. Romney and Gingrich appeared on the cover of the February 6, 2012 issue of Newsweek as gladiators engaged in combat, Gingrich preparing to stab Romney in the back. These and other examples of political gladiators serve, when compared to texts such as Cicero's Pro Sestio, as a means to examine an ancient cultural phenomenon and modern, popularizing appropriations of that phenomenon. -

The Ancient People of Italy Before the Rise of Rome, Italy Was a Patchwork

The Ancient People of Italy Before the rise of Rome, Italy was a patchwork of different cultures. Eventually they were all subsumed into Roman culture, but the cultural uniformity of Roman Italy erased what had once been a vast array of different peoples, cultures, languages, and civilizations. All these cultures existed before the Roman conquest of the Italian Peninsula, and unfortunately we know little about any of them before they caught the attention of Greek and Roman historians. Aside from a few inscriptions, most of what we know about the native people of Italy comes from Greek and Roman sources. Still, this information, combined with archaeological and linguistic information, gives us some idea about the peoples that once populated the Italian Peninsula. Italy was not isolated from the outside world, and neighboring people had much impact on its population. There were several foreign invasions of Italy during the period leading up to the Roman conquest that had important effects on the people of Italy. First there was the invasion of Alexander I of Epirus in 334 BC, which was followed by that of Pyrrhus of Epirus in 280 BC. Hannibal of Carthage invaded Italy during the Second Punic War (218–203 BC) with the express purpose of convincing Rome’s allies to abandon her. After the war, Rome rearranged its relations with many of the native people of Italy, much influenced by which peoples had remained loyal and which had supported their Carthaginian enemies. The sides different peoples took in these wars had major impacts on their destinies. In 91 BC, many of the peoples of Italy rebelled against Rome in the Social War. -

Journey to Antioch, However, I Would Never Have Believed Such a Thing

Email me with your comments! Table of Contents (Click on the Title) Prologue The Gentile Heart iv Part I The Road North 1 Chapter One The Galilean Fort 2 Chapter Two On the Trail 14 Chapter Three The First Camp 27 Chapter Four Romans Versus Auxilia 37 Chapter Five The Imperial Way Station 48 Chapter Six Around the Campfire 54 Chapter Seven The Lucid Dream 63 Chapter Eight The Reluctant Hero 68 Chapter Nine The Falling Sickness 74 Chapter Ten Stopover In Tyre 82 Part II Dangerous Passage 97 Chapter Eleven Sudden Detour 98 Chapter Twelve Desert Attack 101 Chapter Thirteen The First Oasis 111 Chapter Fourteen The Men in Black 116 Chapter Fifteen The Second Oasis 121 Chapter Sixteen The Men in White 128 Chapter Seventeen Voice in the Desert 132 Chapter Eighteen Dark Domain 136 Chapter Nineteen One Last Battle 145 Chapter Twenty Bandits’ Booty 149 i Chapter Twenty-One Journey to Ecbatana 155 Chapter Twenty-Two The Nomad Mind 162 Chapter Twenty-Three The Slave Auction 165 Part III A New Beginning 180 Chapter Twenty-Four A Vision of Home 181 Chapter Twenty-Five Journey to Tarsus 189 Chapter Twenty-Six Young Saul 195 Chapter Twenty-Seven Fallen from Grace 210 Chapter Twenty-Eight The Roman Escorts 219 Chapter Twenty-Nine The Imperial Fort 229 Chapter Thirty Aurelian 238 Chapter Thirty-One Farewell to Antioch 246 Part IV The Road Home 250 Chapter Thirty-Two Reminiscence 251 Chapter Thirty-Three The Coastal Route 259 Chapter Thirty-Four Return to Nazareth 271 Chapter Thirty-Five Back to Normal 290 Chapter Thirty-Six Tabitha 294 Chapter Thirty-Seven Samuel’s Homecoming Feast 298 Chapter Thirty-Eight The Return of Uriah 306 Chapter Thirty-Nine The Bosom of Abraham 312 Chapter Forty The Call 318 Chapter Forty-One Another Adventure 323 Chapter Forty-Two Who is Jesus? 330 ii Prologue The Gentile Heart When Jesus commissioned me to learn the heart of the Gentiles, he was making the best of a bad situation. -

World Archaeology the Animals of the Arena: How and Why Could Their

This article was downloaded by: [Universitetsbiblioteket i Bergen] On: 26 April 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 907435713] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK World Archaeology Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713699333 The animals of the arena: how and why could their destruction and death be endured and enjoyed? Torill Christine Lindstrøm a a Dept of Psychosocial Science, University of Bergen, Online publication date: 23 April 2010 To cite this Article Lindstrøm, Torill Christine(2010) 'The animals of the arena: how and why could their destruction and death be endured and enjoyed?', World Archaeology, 42: 2, 310 — 323 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/00438241003673045 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00438241003673045 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Reading Death in Ancient Rome

Reading Death in Ancient Rome Reading Death in Ancient Rome Mario Erasmo The Ohio State University Press • Columbus Copyright © 2008 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Erasmo, Mario. Reading death in ancient Rome / Mario Erasmo. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1092-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1092-9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Death in literature. 2. Funeral rites and ceremonies—Rome. 3. Mourning cus- toms—Rome. 4. Latin literature—History and criticism. I. Title. PA6029.D43E73 2008 870.9'3548—dc22 2008002873 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1092-5) CD-ROM (978-0-8142-9172-6) Cover design by DesignSmith Type set in Adobe Garamond Pro by Juliet Williams Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI 39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents List of Figures vii Preface and Acknowledgments ix INTRODUCTION Reading Death CHAPTER 1 Playing Dead CHAPTER 2 Staging Death CHAPTER 3 Disposing the Dead 5 CHAPTER 4 Disposing the Dead? CHAPTER 5 Animating the Dead 5 CONCLUSION 205 Notes 29 Works Cited 24 Index 25 List of Figures 1. Funerary altar of Cornelia Glyce. Vatican Museums. Rome. 2. Sarcophagus of Scipio Barbatus. Vatican Museums. Rome. 7 3. Sarcophagus of Scipio Barbatus (background). Vatican Museums. Rome. 68 4. Epitaph of Rufus. -

9.4. South Italic Military Equipment and Identity: 229 9.5

REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree py\D Name of Author Year 2bOfa flJdNS, N\. CO PYRIG HT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the priorwritten consent of the author. LOANS Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the Senate House Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: Inter-Library Loans, Senate House Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the Senate House Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The Senate House Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962 - 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. -

Gladiators and Martyrs Icons in the Arena

Gladiators and Martyrs Icons in the Arena Susan M. (Elli) Elliott Shining Mountain Institute Red Lodge, Montana One of the questions before us for the 2015 spring meeting Christianity Seminar of the Westar Institute is: “Why did martyrdom stories explode in popularity even as Roman violence against early Christians subsided?”1 I propose that the association of Christian martyrs with the popular image of the gladiator, both as failed heroes, as proposed primarily in the work of Carlin A. Barton, is a starting point for addressing this question.2 The martyrs became icons for Christian identity in a Christian vision of the Empire much as the gladiators functioned as icons for the Roman identity in the Roman Empire. The first part of this paper will offer an overview of the Roman arena as both a projection of Roman imperial power and a setting for negotiation of social relations. The second section will focus on the gladiator as a central feature of the spectacle program for which the Roman arenas were constructed and as an icon of Roman identity. The final section will discuss how the presentation of Christian martyrs casts them as gladiators and some of the implications of seeing them in this role. 1 When I learned of the topic for the spring meeting at the fall Westar meeting, I offered to pursue a topic that first occurred to me several years ago while reading Judith Perkins’ ground- breaking work, The Suffering Self: Pain and Narrative Representation in the Early Christian Era (London, New York: Routledge, 1995). This project has taken another direction. -

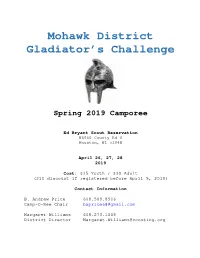

Mohawk District Gladiator's Challenge

Mohawk District Gladiator’s Challenge Spring 2019 Camporee Ed Bryant Scout Reservation N6960 County Rd G Mauston, WI 53948 April 26, 27, 28 2019 Cost: $35 Youth / $30 Adult ($10 discount if registered before April 5, 2019) Contact Information B. Andrew Price 608.509.8506 Camp-O-Ree Chair [email protected] Margaret Williams 608.273.1005 District Director [email protected] Dear Scouts and Scouters, Your Legionary (Troop) is invited to attend the annual Mohawk District Spring Camporee. This year’s theme is “GLADIATOR CHALLENGE ”. Have you ever watched movies or read books based on gladiator warriors of the ancient Roman Empire? If so, then you might have a fairly good idea of what is in store for you at the 2019 Mohawk District Spring Camporee. If not, allow me to enlighten you on what it means to be a gladiator. In ancient Rome, contestants would compete in combat inside large arenas called coliseums. These contestants were called gladiators and were usually of great skill and strength. These gladiatorial competitions were not only physical challenges, but battles of will and sheer determination. Competitions would normally last until only one gladiator or group of gladiators remained. The victor or victors would then compete in numerous other competitions, becoming more skilled and knowledgeable with each consecutive battle. Beloved by the masses, Roman gladiators were the working-class heroes of antiquity. The victorious gladiators would gain wealth and glory for their efforts, and a lucky few were event granted “A wooden sword” and along with it, their freedom. The Mohawk Gladiator’s Challenge will offer the same opportunities for competition and perhaps event victory to a chosen few. -

Italo-Hellenistic Sanctuaries of Pentrian Samnium: Questions of Accessibility

doi: 10.2143/AWE.13.0.3038731 AWE 13 (2014) 63-79 ITALO-HELLENISTIC SANCTUARIES OF PENTRIAN SAMNIUM: QUESTIONS OF ACCESSIBILITY RACHEL VAN DUSEN Abstract This article addresses the region of Pentrian Samnium, located in the Central Apennines of Italy. The traditional view regarding ancient Samnium presents the region as a backwater which was economically marginalised and isolated. This article examines Pentrian religious architecture from the 3rd to the 1st century BC in order to present an alternative reading of the evidence towards a more favourable view of the region with respect to its socio- economic conditions and openness to ideas and developments in Italy. The early 3rd century BC marks a time of great transformation in Italy. Roman imperialism was sweeping through the entire peninsula, large stretches of territory were being seized and Roman power was being solidified via colonies, military camps and unbalanced alliances in many of the regions in both the hinterland and along the coast. Yet, in the midst of these changes one region of Italy remained almost completely intact and autonomous – Pentrian Samnium.1 However, one look at the political map of Italy during this period suggests that while on the inside Pentrian territory, located high in the Central Apennines, remained virtually untouched by Roman encroachment, on the outside it had become entirely surrounded by Roman colonies and polities unquestionably loyal to Rome. Pentrian Samnium was the largest and most long-lived of all the Samnite regions. From the early 3rd century BC onwards, it can be argued that the Pentri made up the only Samnite tribe to have remained truly ‘Samnite’ in its culture and identity. -

Titus's 100 Days of Games “Today Is the Day,” I Told My Mom As I Dashed

Titus’s 100 Days of Games “Today is the day,” I told my mom as I dashed down the stairs. I had been waiting weeks for this to happen. My dad and I were headed to the games! I had been to gladiatorial fights in the forum and at funeral processions, but never huge matches like this. The first ever gladiator match was in 264 BC and it was in a cattle market known as the Forum Boarium to celebrate Brutus Pera. My ancestors watched the whole fight and now it has become a family tradition. Titus has been a horrible leader until today. In 79 AD when he started his reign Mount Vesuvius erupted. The gods clearly were unhappy with his ruling. Now he is in good favor with the people because today he finally opens the games and the Colosseum. His father Vespasian ruled before him and started the building of the Colosseum. I asked my mother, “Did you know, Titus is the first ruler to come to throne after his biological father.” She responded, “Yes sweetie now you better leave for the games your father is waiting for you.” I saw my father in the atrium and we set off. I’ve always admired my father. He is in the Senate therefore he gets to sit in the front right behind the emperor at the Colosseum. Our walk was short and we found little to discuss other than our excitement towards our day to come. We finally arrived at the massive Colosseum. Quickly everyone filed into their seats as the games were about to begin. -

Violence in Sports: a Comparison of Gladiatorial Games in Ancient Rome to the Sports of America Amanda Doherty

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Honors Theses University Honors Program 8-2001 Violence in Sports: A Comparison of Gladiatorial Games in Ancient Rome to the Sports of America Amanda Doherty Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/uhp_theses Name On Title Page: Amanda Stern Recommended Citation Doherty, Amanda, "Violence in Sports: A Comparison of Gladiatorial Games in Ancient Rome to the Sports of America" (2001). Honors Theses. Paper 9. This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ., Violence in Sports: A Comparison of Gladiatorial Games in Ancient Rome to the Sports ofAmerica Amanda Stern Gladiatorial games in Ancient Rome and modem sports have more in common than we would like to believe. Violence has been a key component to the success ofeach ofthese activities. Many spectators watched as the Coliseum was filled with blood from brutal gladiatorial matches. Today, hundreds offans watch as two grown men hit one another in a boxing ring. After examining gladiatorial games and looking at modem sports one may notice similarities between the two. These similarities suggest that modem sports seem to be just as violent as games in Ancient Rome. The Romans believed that they inherited the practice ofgladiatorial games from the Etruscans who used them as part ofa funeral ritual (Grant, 7). The first gladiatorial games were offered in Rome in 264 BCE by sons ofJunius Brutus Pera in their father's honor (Grant, 8).