Syria's Post-Uprising Media Outlets: Challenges and Opportunities In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, Seamus Hughes, Bennett Clifford FEBRUARY 2018

Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, Seamus Hughes, Bennett Clifford FEBRUARY 2018 THE TRAVELERS American Jihadists in Syria and Iraq BY Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, Seamus Hughes, Bennett Cliford Program on Extremism February 2018 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2018 by Program on Extremism Program on Extremism 2000 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20006 www.extremism.gwu.edu Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................v A Note from the Director .........................................................................................vii Foreword ......................................................................................................................... ix Executive Summary .......................................................................................................1 Introduction: American Jihadist Travelers ..........................................................5 Foreign Fighters and Travelers to Transnational Conflicts: Incentives, Motivations, and Destinations ............................................................. 5 American Jihadist Travelers: 1980-2011 ..................................................................... 6 How Do American Jihadist -

U.S. Citizens Kidnapped by the Islamic State John W

CRS Insights U.S. Citizens Kidnapped by the Islamic State John W. Rollins, Specialist in Terrorism and National Security ([email protected], 7-5529) Liana Rosen, Specialist in International Crime and Narcotics ([email protected], 7-6177) February 13, 2015 (IN10167) Overview On February 10, 2015, President Barack Obama acknowledged that U.S. citizen Kayla Mueller was killed while held in captivity by the terrorist group known as the Islamic State (IS). This was the fourth death of an American taken hostage by the Islamic State: Abdul-Rahman Kassig (previously Peter Kassig), James Foley, and Steven Sotloff were also killed. The death of Mueller and the graphic videos depicting the deaths of the other three Americans have generated debate about the U.S. government's role and capabilities for freeing hostages. In light of these deaths, some policymakers have called for a reevaluation of U.S. policy on international kidnapping responses. Questions include whether it is effective and properly coordinated and implemented, should be abandoned or modified to allow for exceptions and flexibility, or could benefit from enhancements to improve global adherence. Scope The killing of U.S. citizens by the Islamic State may be driven by a variety of underlying motives. Reports describe the group as inclined toward graphic and public forms of violence for purposes of intimidation and recruitment. It is unclear whether the Islamic State would have released its Americans hostages in exchange for ransom payments or other concessions. Foley's family, for example, disclosed that the Islamic State demanded a ransom of 100 million euros ($132 million). -

Politcal Science

Politcal Science Do Terrorist Beheadings Infuence American Public Opinion? Sponsoring Faculty Member: Dr. John Tures Researchers and Presenters: Lindsey Weathers, Erin Missroon, Sean Greer, Bre’Lan Simpson Addition Researchers: Jarred Adams, Montrell Brown, Braxton Ford, Jefrey Garner, Jamarkis Holmes, Duncan Parker, Mark Wagner Introduction At the end of Summer 2014, Americans were shocked to see the tele- vised execution of a pair of American journalists in Syria by a group known as ISIS. Both were killed in gruesome beheadings. The images seen on main- stream media sites, and on websites, bore an eerie resemblance to beheadings ten years earlier in Iraq. During the U.S. occupation, nearly a dozen Americans were beheaded, while Iraqis and people from a variety of countries were dis- patched in a similar manner. Analysts still question the purpose of the videos of 2004 and 2014. Were they designed to inspire locals to join the cause of those responsible for the killings? Were they designed to intimidate the Americans and coalition members, getting the public demand their leaders withdraw from the region? Or was it some combination of the two ideas? It is difcult to assess the former. But we can see whether the behead- ings had any infuence upon American public opinion. Did they make Ameri- cans want to withdraw from the Middle East? And did the beheadings afect the way Americans view Islam? To determine answers to these questions, we look to the literature for theories about U.S. public opinion, as well as infuences upon it. We look at whether these beheadings have had an infuence on survey data of Americans across the last dozen years. -

The James W. Foley Journalism Safety Modules

The James W. Foley Journalism Safety Modules UPDATED: May 3, 2021 Developed in collaboration with the Marquette University Diederich College of Communication ii Contents Lessons for Undergraduate Journalism and Communications Programs: An Overview .........................1 Module 1: Introduction to Journalism Safety ......................................................................................2 BE SAFE (Before Everything Stop Assess Focus Enact) ............................................................................. 2 “Six months later, the Capital-Gazette shooting still resonates, among family, community, news industry” Jean Marbella, The Baltimore Sun ............................................................................................ 3 “Doing No Harm: The Call for Crime Reporting that Does Justice to the Beat” Natalie Yahr, Center for Journalism Ethics ...................................................................................................................................... 3 “We Need to Talk About the Dangers of Journalism” Melanie Pineda, Washington Square News......... 4 Module 2: Developing Safe Journalistic Habits ....................................................................................5 Risk Assessments for Journalists .............................................................................................................. 5 “For student journalists, the beats are the same but the protections are different” Stephanie Sugars, Freedom of the Press Foundation ............................................................................................................ -

TITLE Ll—AUTHORITY for the USE of MILITARY FORCE AGAINST

DAV15E09 S.L.C. AMENDMENT NO.llll Calendar No.lll Purpose: To authorize the use of the United States Armed Forces against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES—114th Cong., 1st Sess. (no.) lllllll (title) llllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll Referred to the Committee on llllllllll and ordered to be printed Ordered to lie on the table and to be printed AMENDMENT intended to be proposed by Mr. KAINE (for himself and Mr. FLAKE) Viz: 1 At the appropriate place, insert the following: 2 TITLE ll—AUTHORITY FOR 3 THE USE OF MILITARY FORCE 4 AGAINST THE ISLAMIC STATE 5 OF IRAQ AND THE LEVANT 6 SEC. l1. SHORT TITLE. 7 This title may be cited as the ‘‘Authority for the Use 8 of Military Force Against the Islamic State of Iraq and 9 the Levant Act’’. 10 SEC. l2. FINDINGS. 11 Congress makes the following findings: DAV15E09 S.L.C. 2 1 (1) The terrorist organization that has referred 2 to itself as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant 3 and various other names (in this resolution referred 4 to as ‘‘ISIL’’) poses a grave threat to the people and 5 territorial integrity of Iraq and Syria, regional sta- 6 bility, and the national security interests of the 7 United States and its allies and partners. 8 (2) ISIL holds significant territory in Iraq and 9 Syria and has stated its intention to seize more ter- 10 ritory and demonstrated the capability to do so. 11 (3) ISIL leaders have stated that they intend to 12 conduct terrorist attacks internationally, including 13 against the United States, its citizens, and interests. -

After Foley Killing, US Defends Refusal to Pay Ransom To

The Obama administration sharply defended its refusal to negotiate with or pay ransom to terrorist groups that kidnap, following the videotaped execution this week of American photojournalist James Foley by the Islamic State. “We believe that paying ransoms or making concessions would put all Americans overseas at greater risk” and would provide funding for groups whose capabilities “we are trying to degrade,” Marie Harf, a State Department spokeswoman, said in a briefing Thursday. Harf said it is illegal for any American citizen to pay ransom to a group, such as the Islamic State, that the U.S. government has designated as a terrorist organization. ADVERTISING In late 2013, more than a year after Foley was captured while reporting on Syria’s civil war, his family received several e-mails from the Islamic State, including one demanding 100 million Euros, about $133 million, for his freedom, according to GlobalPost, Foley’s employer. The amount, many times the ransom demanded for other Western hostages, indicated that the Islamic State was not serious about releasing Foley, U.S. officials said. His family and GlobalPost agreed, said Richard Byrne, the company’s vice president and director of communications. “I don’t think there was a negotiation,” he said. GlobalPost has said that it shared with federal officials all communications it received from the kidnappers, including a final e-mail last week saying they were about to execute Foley. Earlier this summer, U.S. Special Operations forces had tried to rescue Foley and three other Americans known to be held by the Islamic State. Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel on Thursday described the raid — in which one U.S. -

Song, State, Sawa Music and Political Radio Between the US and Syria

Song, State, Sawa Music and Political Radio between the US and Syria Beau Bothwell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Beau Bothwell All rights reserved ABSTRACT Song, State, Sawa: Music and Political Radio between the US and Syria Beau Bothwell This dissertation is a study of popular music and state-controlled radio broadcasting in the Arabic-speaking world, focusing on Syria and the Syrian radioscape, and a set of American stations named Radio Sawa. I examine American and Syrian politically directed broadcasts as multi-faceted objects around which broadcasters and listeners often differ not only in goals, operating assumptions, and political beliefs, but also in how they fundamentally conceptualize the practice of listening to the radio. Beginning with the history of international broadcasting in the Middle East, I analyze the institutional theories under which music is employed as a tool of American and Syrian policy, the imagined youths to whom the musical messages are addressed, and the actual sonic content tasked with political persuasion. At the reception side of the broadcaster-listener interaction, this dissertation addresses the auditory practices, histories of radio, and theories of music through which listeners in the sonic environment of Damascus, Syria create locally relevant meaning out of music and radio. Drawing on theories of listening and communication developed in historical musicology and ethnomusicology, science and technology studies, and recent transnational ethnographic and media studies, as well as on theories of listening developed in the Arabic public discourse about popular music, my dissertation outlines the intersection of the hypothetical listeners defined by the US and Syrian governments in their efforts to use music for political ends, and the actual people who turn on the radio to hear the music. -

Gw Extremism Tracker Terrorism in the United States

GW EXTREMISM TRACKER TERRORISM IN THE UNITED STATES INDIVIDUALS HAVE BEEN CHARGED IN THE U.S. ON OFFENSES RELATED 217 to the Islamic State (also known as IS, ISIS, and ISIL) since March 2014, when the first arrests occurred. Of those: Their activities were located in 30 states and the District of Columbia the average age of are male 90% 28 those charged. have pleaded or * the average length 157 were found guilty 13.2 of sentence in years. *Uses 470 months for life sentences per the practice of the U.S. Sentencing Commission were accused of attempting 39% to travel or successfully traveled abroad. were accused of being 31% involved in plots to carry out attacks on U.S. soil. were charged in an operation MALE 58% involving an informant and/or an undercover agent. FEMALE indicates law enforcement operation Acknowledgement Disclaimer This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as under Grant Award Number 20STTPC00001‐01 necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Apprehensions & Charges for Other conspirators were involved in the IS “hostage-taking scheme,” which resulted in the kidnapping and subsequent death of Jihadist Groups James Foley, Kayla Mueller, Steven Sotloff, Peter Kassig, as well as British and Japanese nationals. The pair, who also face material support charges, were captured in January of 2018 by OCT 21 VA the Syrian Democratic Forces and transferred to American custody in 2019. -

Syria's Future and the War Against ISIS

14 October 2014 Syria's Future and the War against ISIS How will the military campaign against ISIS affect Syria over the long-term? Murhaf Jouejati warns that unless Washington actively trains, equips and politically accommodates ‘moderate’ Syrian opposition forces, the greatest beneficiary of the intervention could indeed be the Assad regime. By Murhaf Jouejati for ISN On 10 September 2014, US President Barack Obama publicly declared war on ISIS with the goal of degrading and destroying the extremist organization. Obama’s new stance was an escalation of his earlier, more limited decision to use American airpower against ISIS in western Iraq. In his televised speech, Obama affirmed that he would not hesitate to strike at ISIS targets in Syria as well – without seeking the Assad regime’s authorization. What explains the shift from Obama’s earlier “hands off” approach towards Syria, and how will the new approach affect that war-torn country? The shift in Obama’s approach The trigger for the dramatic shift in American policy was the beheading by ISIS fighters of two American journalists, James Foley and Steven Sotloff. Against this backdrop, widespread criticism regarding Obama’s passive Syria policy had been mounting steadily. Critics took Obama to task for not having intervened in Syria’s civil war earlier, when the emergence of ISIS might have been prevented. Many argued that the negative ramifications of Obama’s passivity went beyond Syria: it emboldened Russia to annex Crimea and destabilize Ukraine, and hardened Iran’s stance in the nuclear talks -- without the fear of major retribution. At the end of the day, what forced Obama’s hand was the combination of this stinging criticism, pressure from sustained lobbying efforts by key US allies, and the significant shift in American public opinion (before the beheadings, 68% of Americans were “for” delaying the use of airpower. -

Right to Act: United States Legal Basis Under the Law of Armed Conflict to Pursue the Islamic State in Syria Samantha Arrington Sliney

University of Miami Law School Institutional Repository University of Miami National Security & Armed Conflict Law Review November 2015 Right to Act: United States Legal Basis Under the Law of Armed Conflict to Pursue the Islamic State in Syria Samantha Arrington Sliney Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umnsac Part of the International Law Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Recommended Citation Samantha Arrington Sliney, Right to Act: United States Legal Basis Under the Law of Armed Conflict to Pursue the Islamic State in Syria, 6 U. Miami Nat’l Security & Armed Conflict L. Rev. 1 () Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umnsac/vol6/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami National Security & Armed Conflict Law Review by an authorized administrator of Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Right to Act: United States Legal Basis Under the Law of Armed Conflict to Pursue the Islamic State in Syria Samantha Arrington Sliney* I. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................... 1 II. HISTORY OF THE ISLAMIC STATE ........................................................ 4 III. THE ISLAMIC STATE’S IDEOLOGY ...................................................... 6 IV. TAKE OVER OF SYRIA AND IRAQ, JUNE 2014 TO PRESENT: AN OVERVIEW ........................................................................................ -

Syria Timeline 2011–2016

Syria Timeline 2011–2016 COLOR KEY: ■ EVENTS IN SYRIA ■ HUMAN RIGHTS FIRST REPORTS ■ U.S. GOVERNMENT ACTIONS/STATEMENTS 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 —— MARCH —— JANUARY 23 —— FEBRUARY 28 —— JANUARY-FEBRUARY —— FEBRUARY 17 —— FEBRUARY 1-FEBRUARY 3 Jabhat al-Nusra announces Enablers of the Syrian Conflict The first two rounds of peace talks attended The United States reaches an agreement with U.N.-mediated Syria peace talks begin in its formation as Syria’s —— MARCH 21 by the Syrian government and the National Turkey on training and arming Syrian rebels Geneva, but are swiftly suspended. official al-Qaeda affiliate. The United Nations investigates the possible use of chemical Opposition Coalition begin in Geneva. No fighting ISIS. —— FEBRUARY 22 progress is made. —— FEBRUARY 4 weapons in Syria. —— MAY 21 The United States and Russia announce that a Russia and China veto —— JUNE 13 —— FEBRUARY 10 ISIS takes control of Palmyra, a UNESCO World partial ceasefire in Syria will start on February a U.S.-backed U.N. Deputy National Security Advisor Ben Rhodes: “Our Addressing Barriers to the Resettlement of Heritage Site. 27. The ceasefire does not apply to attacks on Security Council resolution intelligence community assesses that the Assad regime has Vulnerable Syrian and Other Refugees —— SEPTEMBER 30 U.N.-designated terrorist organizations. condemning the violence used chemical weapons, including the nerve agent sarin, on —— JUNE 3 Russia carries out its first airstrikes in Syria. Its —— FEBRUARY and calling for a political a small scale against the opposition multiple times in the last President Assad wins elections in government- operations target the U.S.-supported non-ISIS The Syrian Refugee Crisis and the Need for transition. -

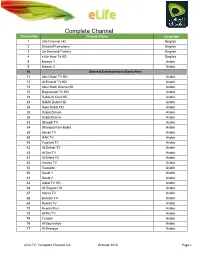

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad