Excerpted From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reservation Package

THE BAHAMAS - SOUTHERN EXUMA CAYS RESERVATION PACKAGE Toll free 1 800 307 3982 | Overseas 1 250 285 2121 | [email protected] | kayakingtours.com SOUTHERN EXUMA CAYS EXPEDITION 5 NIGHTS / 6 DAYS SEA KAYAK EXPEDITION & BEACH CAMPING | GEORGE TOWN DEPARTURE Please read through this package of information to help you to prepare for your tour. Please also remember to return your signed medical information form as soon as possible and read and understand the liability waiver which you will be asked to sign upon arrival. We hope you are getting excited for your adventure! ITINERARY We are so glad that you will be joining us for this incred- which dry out at low tide. This makes it a great place ible adventure. This route will take us into the stunning for exploring by kayak as most boats cannot access Exuma Cays. The bountiful and rich wildlife (including this shallow area. Our destination for tonight is either colourful tropical fish, corals, sea turtles and many Long Cay (apx 7 miles) or Brigantine Cay (apx 9 miles). species of birds), long sandy beaches and clear blue Once there we will set up camp, snorkel and relax. water will help you to fall in love with the Bahamas. DAY 2 After breakfast we will pack up camp and continue DAY PRIOR exploring the Brigantine Cays. The Cays are home to Depart your home for the Bahamas today or earli- several different types of mangrove forests. If the tides er if you wish. There are direct flights from Toronto to are right we will paddle through some of these incred- George Town several days a week or if coming from ibly important and diverse ecosystems which are of- other locations, the easiest entry point is to arrive into ten nursery habitat for all sorts of fish species, small Nassau. -

West Indian Iguana Husbandry Manual

1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 Natural history ............................................................................................................................... 7 Captive management ................................................................................................................... 25 Population management .............................................................................................................. 25 Quarantine ............................................................................................................................... 26 Housing..................................................................................................................................... 26 Proper animal capture, restraint, and handling ...................................................................... 32 Reproduction and nesting ........................................................................................................ 34 Hatchling care .......................................................................................................................... 40 Record keeping ........................................................................................................................ 42 Husbandry protocol for the Lesser Antillean iguana (Iguana delicatissima)................................. 43 Nutrition ...................................................................................................................................... -

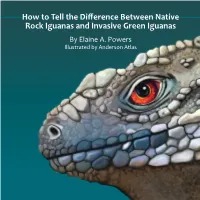

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

Marina Status: Open with Exceptions

LATEST COVID-19 INFORMATION BRILAND CLUB MARINA HARBOUR ISLAND, THE BAHAMAS UPDATED AUGUST 6, 2021 MARINA STATUS: OPEN WITH EXCEPTIONS Effective Friday, August 6, 2021, those persons applying for a travel health visa to enter The Bahamas or travel within The Bahamas will be subjected to the following new testing requirements: Entering The Bahamas Vaccinated Travelers All fully vaccinated travelers wishing to enter The Bahamas will now be required to obtain a COVID-19 test (Rapid Antigen Test or PCR), with a negative result, within five days of arrival in The Bahamas. Unvaccinated Travelers There are no changes to the testing requirements for unvaccinated persons wishing to enter The Bahamas. All persons, who are 12 years and older and who are unvaccinated, will still be required to obtain a PCR test taken within five days of arrival in The Bahamas. Children and Infants All children, between the ages of 2 and 11, wishing to enter The Bahamas will now be required to obtain a COVID-19 test (Rapid Antigen Test or PCR), with a negative result, within five days of arrival in The Bahamas. All children, under the age of 2, are exempt from any testing requirements. Once in possession of a negative COVID-19 RT-PCR test and proof of full vaccination, all travelers will then be required to apply for a Bahamas Health Travel Visa at travel.gov.bs (click on the International Tab) where the required test must be uploaded. LATEST COVID-19 INFORMATION BRILAND CLUB MARINA HARBOUR ISLAND, THE BAHAMAS UPDATED AUGUST 6, 2021 Traveling within The Bahamas Vaccinated Travelers All fully vaccinated travelers wishing to travel within The Bahamas, will now be required to obtain a COVID-19 test (Rapid Antigen Test or PCR), with a negative result, within five days of the travel date from the following islands: New Providence, Grand Bahama, Bimini, Exuma, Abaco and North and South Eleuthera, including Harbour Island. -

Redalyc.Photosynthetic Performance of Mangroves Rhizophora Mangle

Revista Árvore ISSN: 0100-6762 [email protected] Universidade Federal de Viçosa Brasil Ralph Falqueto, Antelmo; Moura Silva, Diolina; Venturim Fontes, Renata Photosynthetic performance of mangroves Rhizophora mangle and Laguncularia racemosa under field conditions Revista Árvore, vol. 32, núm. 3, mayo-junio, 2008, pp. 577-582 Universidade Federal de Viçosa Viçosa, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=48813382018 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Photosynthetic performance of magroves … 577 PHOTOSYNTHETIC PERFORMANCE OF MANGROVES Rhizophora mangle AND Laguncularia racemosa UNDER FIELD CONDITIONS1 Antelmo Ralph Falqueto2, Diolina Moura Silva3, Renata Venturim Fontes4 ABSTRACT – In mature mangrove plants Rhizophora mangle L. and Laguncularia racemosa Gaerth. growing under field conditions, photosystem 2 (PS2) photochemical efficiency, determined by the ratio of variable to maximum fluorescence (Fv/Fm), increased during the day in response to salinity in the rainy seasons. During the dry season, fluorescence values ( Fo) were higher than those observed in rainy season. In addition, Fo decreased during the day in both season and species, except for R. mangle during the dry season. A positive correlation among Fv/Fm and salinity values was obtained for R. mangle and L. Racemosa during the dry and rainy seasons, showing that photosynthetic performance is maintained in both species under high salinities. Carotenoid content was higher in L. Racemosa in both seasons, which represents an additional mechanism against damage to the photosynthetic machinery. -

Influence of Propagule Flotation Longevity and Light

Influence of Propagule Flotation Longevity and Light Availability on Establishment of Introduced Mangrove Species in Hawai‘i1 James A. Allen2,3 and Ken W. Krauss2,4,5 Abstract: Although no mangrove species are native to the Hawaiian Archipel- ago, both Rhizophora mangle and Bruguiera sexangula were introduced and have become naturalized. Rhizophora mangle has spread to almost every major Ha- waiian island, but B. sexangula has established only on O‘ahu, where it was inten- tionally introduced. To examine the possibility that differences in propagule characteristics maintain these patterns of distribution, we first reviewed the lit- erature on surface currents around the Hawaiian Islands, which suggest that propagules ought to disperse frequently from one island to another within 60 days. We then tested the ability of propagules of the two species to float for pe- riods of up to 63 days and to establish under two light intensities. On average, R. mangle propagules floated for longer periods than those of B. sexangula, but at least some propagules of both species floated for a full 60 days and then rooted and grew for 4 months under relatively dense shade. A large percentage (@83%) of R. mangle propagules would be expected to float beyond 60 days, and approx- imately 10% of B. sexangula propagules also would have remained afloat. There- fore, it seems likely that factors other than flotation ability are responsible for the failure of B. sexangula to become established on other Hawaiian islands. The Hawaiian Archipelago, located in Mangrove species were first introduced to the central Pacific Ocean between 18 and Hawai‘i in 1902, when Rhizophora mangle L. -

Iguanas and Seabirds

PROTECTEDAREASMANAGEMENTSTRATEGYFOR BAHAMIAN TERRESTRIAL VERTEBRATES: IGUANAS AND SEABIRDS Bahamian Field Station San Salvador, The Bahamas 11-12 November, 2000 Organized by Conservation Unit, Bahamas Department of Agriculture and IUCN/SSC Iguana Specialist Group In collaboration with IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group Supported by Fort Worth Zoo Zoological Society of San Diego A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group. Organized by Conservation Unit, Bahamas Department of Agriculture and the IUCN/SSC Iguana Specialist Group, in collaboration with the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group. Supported by the Fort Worth Zoo and the Zoological Society of San Diego. © Copyright 2001 by CBSG. Citation: E. Carey, S.D. Buckner, A. C. Alberts, R.D. Hudson, and D. Lee, editors. 2001. Protected Areas Management Strategy for Bahamian Terrestrial Vertebrates: Iguanas and Seabirds. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, Apple Valley, Minnesota. Additional copies of Protected Areas Management Strategy for Bahamian Terrestrial Vertebrates: Iguanas and Seabirds Report can be ordered through the the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124. Bartschi s iguana, Cyclura carinata bartschi Andros island iguana, Cyclura cychlura cychlura Exuma island iguana, Cyclura cychlura figginsi Allen s Cay iguana, Cyclura cychlura inornata Allen s Cay iguana, Cyclura cychlura inornata Acklins iguana, Cyclura rileyi nucha/is San Salvador iguana, Cyclura rileyi rileyi San Salvador iguana, Cyclura rileyi rileyi Audubon s Shearwater, Puffinus lherminieri Least Tern, Sterna antillarum White-tailed Tropicbird, Phaethon lepturus Brown Booby, Sula leucogaster Bridled Tern, Sterna anaethetus Magnificent Frigatebird, Fregata magnificens - Juveniles CONTENTS Opening Remarks by The Bahamas Minister of Commerce, Agriculture, and Industry ......................... -

Iguanid and Varanid CAMP 1992.Pdf

CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR IGUANIDAE AND VARANIDAE WORKING DOCUMENT December 1994 Report from the workshop held 1-3 September 1992 Edited by Rick Hudson, Allison Alberts, Susie Ellis, Onnie Byers Compiled by the Workshop Participants A Collaborative Workshop AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group SPECIES SURVIVAL COMMISSION A Publication of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124 USA A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, and the AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group. Cover Photo: Provided by Steve Reichling Hudson, R. A. Alberts, S. Ellis, 0. Byers. 1994. Conservation Assessment and Management Plan for lguanidae and Varanidae. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. Additional copies of this publication can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124. Send checks for US $35.00 (for printing and shipping costs) payable to CBSG; checks must be drawn on a US Banlc Funds may be wired to First Bank NA ABA No. 091000022, for credit to CBSG Account No. 1100 1210 1736. The work of the Conservation Breeding Specialist Group is made possible by generous contributions from the following members of the CBSG Institutional Conservation Council Conservators ($10,000 and above) Australasian Species Management Program Gladys Porter Zoo Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Sponsors ($50-$249) Chicago Zoological -

Nest Density and Success of Columbids in Puerto Rico ’

The Condor98:1OC-113 0 The CooperOrnithological Society 1996 NEST DENSITY AND SUCCESS OF COLUMBIDS IN PUERTO RICO ’ FRANK F. RIVERA-MILAN~ Department ofNatural Resources,Scientific Research Area, TerrestrialEcology Section, Stop 3 Puerta. de Tierra, 00906, Puerto Rico Abstract. A total of 868 active nests of eight speciesof pigeonsand doves (columbids) were found in 210 0.1 ha strip-transectssampled in the three major life zones of Puerto Rico from February 1987 to June 1992. The columbids had a peak in nest density in May and June, with a decline during the July to October flocking period, and an increasefrom November to April. Predation accountedfor 8 1% of the nest lossesobserved from 1989 to 1992. Nest cover was the most important microhabitat variable accountingfor nest failure or successaccording to univariate and multivariate comparisons. The daily survival rate estimates of nests constructed on epiphytes were significantly higher than those of nests constructedon the bare branchesof trees. Rainfall of the first six months of the year during the study accounted for 67% and 71% of the variability associatedwith the nest density estimatesof the columbids during the reproductivepeak in the xerophytic forest of Gulnica and dry coastal forest of Cabo Rojo, but only 9% of the variability of the nest density estimatesof the columbids in the moist montane second-growthforest patchesof Cidra. In 1988, the abundance of fruits of key tree species(nine speciescombined) was positively correlatedwith the seasonalchanges in nest density of the columbids in the strip-transects of Cayey and Cidra. Pairwise density correlationsamong the columbids suggestedparallel responsesof nestingpopulations to similar or covarying resourcesin the life zones of Puerto Rico. -

Abacos Acklins Andros Berry Islands Bimini Cat Island

ABACOS ACKLINS ANDROS BERRY ISLANDS BIMINI CAT ISLAND CROOKED ISLAND ELEUTHERA EXUMAS HARBOUR ISLAND LONG ISLAND RUM CAY SAN SALVADOR omewhere O UT there, emerald wa- ters guide you to a collection of islands where pink Ssands glow at sunset, where your soul leaps from every windy cliff into the warm, blue ocean below. And when you anchor away in a tiny island cove and know in your heart that you are its sole inhabitant, you have found your island. It happens quietly, sud- denly, out of the blue. I found my island one day, OUT of the blue. OuT of the blue. BIMINI ACKLINS & Fishermen love to tell stories about CROOKED ISLAND the one that got away… but out Miles and miles of glassy water never here in Bimini, most fishermen take deeper than your knees make the home stories and photos of the bonefishermen smile. There’s nothing big one they actually caught! Just out here but a handful of bone- 50 miles off the coast of Miami, fishing lodges, shallow waters and Bimini is synonymous with deep still undeveloped wilderness. Endless sea fishing and the larger-than-life blue vistas and flocks of flaming-pink legend of Hemingway (a frequent flamingos are the well kept secrets Something Borrowed, adventurer in these waters). You’re of these two peculiar little islands, never a stranger very long on this separated only by a narrow passage Something Blue. fisherman’s island full of friendly called “The Going Through.” smiles and record-setting catches. Chester’s Highway Inn A wedding in the Out Islands of the Bahamas is a Resorts World Bimini Bonefish Lodge wedding you will always remember. -

The American Loyalists in the Bahama Islands: Who They Were

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 40 Number 3 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 40, Article 3 Issue 3 1961 The American Loyalists in the Bahama Islands: Who They Were Thelma Peters Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Peters, Thelma (1961) "The American Loyalists in the Bahama Islands: Who They Were," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 40 : No. 3 , Article 3. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol40/iss3/3 Peters: The American Loyalists in the Bahama Islands: Who They Were THE AMERICAN LOYALISTS IN THE BAHAMA ISLANDS: WHO THEY WERE by THELMA PETERS HE AMERICAN LOYALISTS who moved to the Bahama Islands T at the close of the American Revolution were from many places and many walks of life so that classification of them is not easy. Still, some patterns do emerge and suggest a prototype with the following characteristics: a man, either first or second gen- eration from Scotland or England, Presbyterian or Anglican, well- educated, and “bred to accounting.” He was living in the South at the time of the American Revolution, either as a merchant, the employee of a merchant, or as a slave-owning planter. When the war came he served in one of the volunteer provincial armies of the British, usually as an officer. -

21 Sep 2018 Lists of Victims and Hosts of the Parasitic

version: 21 Sep 2018 Lists of victims and hosts of the parasitic cowbirds (Molothrus). Peter E. Lowther, Field Museum Brood parasitism is an awkward term to describe an interaction between two species in which, as in predator-prey relationships, one species gains at the expense of the other. Brood parasites "prey" upon parental care. Victimized species usually have reduced breeding success, partly because of the additional cost of caring for alien eggs and young, and partly because of the behavior of brood parasites (both adults and young) which may directly and adversely affect the survival of the victim's own eggs or young. About 1% of all bird species, among 7 families, are brood parasites. The 5 species of brood parasitic “cowbirds” are currently all treated as members of the genus Molothrus. Host selection is an active process. Not all species co-occurring with brood parasites are equally likely to be selected nor are they of equal quality as hosts. Rather, to varying degrees, brood parasites are specialized for certain categories of hosts. Brood parasites may rely on a single host species to rear their young or may distribute their eggs among many species, seemingly without regard to any characteristics of potential hosts. Lists of species are not the best means to describe interactions between a brood parasitic species and its hosts. Such lists do not necessarily reflect the taxonomy used by the brood parasites themselves nor do they accurately reflect the complex interactions within bird communities (see Ortega 1998: 183-184). Host lists do, however, offer some insight into the process of host selection and do emphasize the wide variety of features than can impact on host selection.