Powerbuilder Datawindows to Web

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 Approved Capital Budget

2011 Approved Capital Budget City of Windsor Table of Contents Section Page A Summary of 5-Year Capital Budget .............................…………………………………………... 1 B 5-Year Capital Project Listing by Major Category……………………………………………… 5 C 5-Year Summary of Capital Budget by Funding Source………………………………………… 13 D Summary of Growth vs. Maintenance Related Projects (Gross Expenditure Level)………….. 29 E Summary of Growth vs. Maintenance Related Projects (Net Expenditure Level)…………….. 38 F Capital Project Summaries Agencies and Boards ……………………………………………………………………… 47 Office of Community Development and Health ………………………………………… 70 Office of the Chief Administrative Officer ……………………………………………… 91 Office of the Chief Financial Officer …………………………………………………….. 96 Office of the City Clerk ………………………………………………………………….... 121 Office of the City Engineer ……………………………………………………………….. 138 Office of the City Solicitor ………………………………………………………………... 297 2011 Approved Capital Budget Section A: Summary of 5 -Year Capital Budget 1 of 321 Summary of Capital Budget Expenditures and Funding Sources ($ 000's) for Budget Year 2011 (5-Year Capital Plan)*** Internal Pay As You Go Corporate Reserves External Sources Pay As You Go Pay As You Go Capital Development Infrastructure Recreation Pay As You Go Other Provincial Federal Fuel Tax ** Other Third-Party Year Operating Sewer Expenditure Charges Stimulus Funding Infrastructure Total Debt Reduction Reserves Transit Funding Funding One-time Recoveries Budget Surcharge Reserve Reserves (ISF) Funding (RInC) APPROVED 446 31,841 52,000 3,784 -

Download EAGLE Data Sheet

600 Full Frames Per Second Motion Analysis System The Eagle is a Complete600 Motion Full FramesAnalysis System Per Secondthat can help Motion solve your Analysis mechanical System issues that happen too fast for the eye to see and be analyzed. Everything is in one precise package in a Storage / Shipping / Carrying Case. Included in this package are the USB 3.0 Camera, Lens, USB 3.0 Cable, Box Computer, Remote Control Tablet, EAGLE Camera Interface USB Software, plus additional Cameras if needed. A separate Accessory Package includes a choice of Box Computer Battery, Battery Powered Lights, Lenses, ImageWarp Motion Analysis Software, Floor Tripods, Bench Tripods and a Handheld Tripod also in a Pelican Storage/Carrying Case. Features – IMI USB 3.0 Camera IMB-3213UP Mono; IMC-3213UP Color • VGA 640 x 480 • Max. 600 fps • CMOS Global/Rolling Shutter • High Bandwidth and Low CPU usage • Power Supply Management Support • Plug and Play Interface • 44(W) x 44 (H) x 22.4 (D) mm. 55g Features – Camera Interface Software Development Kit • Provides easy integration into multiple programming environments (C++, C#, VB, NET, VB6, Delphi, PowerBuilder, Java, Python, QT, and more) • Includes drivers for DirectShow, TWAIN, MATLAB, LabVIEW, InduSoft Studio, WinCC Flexible, GE Fanuc Features – Cable and Lenses • PCIe 2-meter cable DIN to DIN CSP-6 Quad • Ships with three lenses • Ships with Pelican Case Applications • FPD and PCB Inspection • Semiconductor Inspection • Digitizing and Scanning • Research and Scientific Imaging • Bottling, Labeling, and Packaging • Mechanical Product Design • Mechanical Engineering Lab Tool Overview The ImageOps Division of Computer Modules has found that the market needs a Complete Motion Analysis System that can solve mechanical issues. -

Developers Choice

IDE Scorecard Developers’ Choice IDE Scorecard Definitive Rankings of the Top 11 IDEs by Over 1,200 Developers June 2006 Evans Data Corp, 740 Front St, Santa Cruz, CA 95060 www.evansdata.com (800) 831 3080 IDE Scorecard I NSIDE T HIS R EPORT Overview 1 Overview Abstract and Methodology 3 Overall Usage In Spring 2006, Evans Data Corp conducted primary market research on IDEs, interviewing over 1200 developers worldwide and asking them to rate 4 Feature Rankings the top IDEs. Developers only rated the features of those IDEs that they had 5 Further Information used. They were asked to rank sixteen different features commonly found in IDEs. Each feature could be ranked as “excellent, “very good” “adequate”, “needs improvement” or “NA”. During processing, the first four rankings were assigned a numerical value according to their relative significance. The last value (“N/A”) was discarded. Values were then combined to produce a score for each element for every IDE and also for an overall total score. The top 11 IDEs ranked were: “Eclipse is well on its Adobe/Macromedia Studio 8 way to becoming one Borland Delphi of the most popular Borland JBuilder IDEs for any Eclipse language..” IBM Rational Application Developer IBM WebSphere Studio Microsoft Visual Studio .NET NetBeans Oracle JDeveloper Sun Java Studio Sybase PowerBuilder Features and capabilities rated were: Compiler/Interpreter Debugger Editor Make/Build Functions Documentation Application Modeling Tools Web Design Tools Sample Applications Profiler 1 IDE Scorecard IDE Scorecard Overview Cont’ Compiler Performance Performance of Resulting Applications Ease of Use Ability to Integrate 3rd Party Tools Availability of 3rd Party Tools Quality of Technical Support Options Size and Quality of Developer Community In addition, developers were asked to rate the IDEs based on how well suited they are for creating a particular type of application (server-centric, desktop, thin-client, rich-client, and embedded systems). -

The Progress Datadirect for ODBC for SQL Server Wire Protocol User's Guide and Reference

The Progress DataDirect® for ODBC for SQL Server™ Wire Protocol User©s Guide and Reference Release 8.0.2 Copyright © 2020 Progress Software Corporation and/or one of its subsidiaries or affiliates. All rights reserved. These materials and all Progress® software products are copyrighted and all rights are reserved by Progress Software Corporation. The information in these materials is subject to change without notice, and Progress Software Corporation assumes no responsibility for any errors that may appear therein. The references in these materials to specific platforms supported are subject to change. Corticon, DataDirect (and design), DataDirect Cloud, DataDirect Connect, DataDirect Connect64, DataDirect XML Converters, DataDirect XQuery, DataRPM, Defrag This, Deliver More Than Expected, Icenium, Ipswitch, iMacros, Kendo UI, Kinvey, MessageWay, MOVEit, NativeChat, NativeScript, OpenEdge, Powered by Progress, Progress, Progress Software Developers Network, SequeLink, Sitefinity (and Design), Sitefinity, SpeedScript, Stylus Studio, TeamPulse, Telerik, Telerik (and Design), Test Studio, WebSpeed, WhatsConfigured, WhatsConnected, WhatsUp, and WS_FTP are registered trademarks of Progress Software Corporation or one of its affiliates or subsidiaries in the U.S. and/or other countries. Analytics360, AppServer, BusinessEdge, DataDirect Autonomous REST Connector, DataDirect Spy, SupportLink, DevCraft, Fiddler, iMail, JustAssembly, JustDecompile, JustMock, NativeScript Sidekick, OpenAccess, ProDataSet, Progress Results, Progress Software, ProVision, PSE Pro, SmartBrowser, SmartComponent, SmartDataBrowser, SmartDataObjects, SmartDataView, SmartDialog, SmartFolder, SmartFrame, SmartObjects, SmartPanel, SmartQuery, SmartViewer, SmartWindow, and WebClient are trademarks or service marks of Progress Software Corporation and/or its subsidiaries or affiliates in the U.S. and other countries. Java is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates. Any other marks contained herein may be trademarks of their respective owners. -

Kristen Elizabeth Bossio

Kristen Elizabeth Bossio [email protected] • (413)841-6824 LinkedIn Profile Current Address: Permanent Address: 515 Loudon Road 87 Rockland Drive Loudonville, NY 12211 Pittsfield, MA 01201 Education: Siena College, Loudonville, NY ! Bachelor of Science in Computer Science, Bachelor of Arts in Creative Arts ! Anticipated Graduation: May 2016 ! Current GPA: 3.91 Technical Skills: ! Languages: Java, JavaScript, JQuery, HTML, CSS, SQL ! Tools & Databases: NetBeans, BlueJ, PowerBuilder, Synergy, Oracle, Sybase ! Web application development using a Struts framework, Ajax, Servlets, Java Beans, and Java Factories Work Experience: Software Engineering Intern (May 2015-August 2015) General Dynamics Mission Systems, Pittsfield, MA ! Developed and tested web applications in support of Repair Operations Management System (ROMS) and Engineering Parts List (EPL) ! Worked directly with end users and application experts to define software capabilities and interface design ! Documented software requirements Video Production Intern (January 2015-May 2015) Office of Marketing and Communications, Siena College, Loudonville, NY ! Produced video content for the Siena College website and YouTube channel ! Directed, shot, and edited a promotional video for a fellow student’s Kickstarter page Waitress/Hostess (June 2012-August 2014) Applebee’s, Pittsfield, MA Extracurricular and Leadership Experience: Stage 3 Theatre Club (September 2012 – present) Siena College, Loudonville, NY ! Served on the Executive Board as Vice President (2015-2016), Secretary (2014-2015), -

Towards Left Duff S Mdbg Holt Winters Gai Incl Tax Drupal Fapi Icici

jimportneoneo_clienterrorentitynotfoundrelatedtonoeneo_j_sdn neo_j_traversalcyperneo_jclientpy_neo_neo_jneo_jphpgraphesrelsjshelltraverserwritebatchtransactioneventhandlerbatchinsertereverymangraphenedbgraphdatabaseserviceneo_j_communityjconfigurationjserverstartnodenotintransactionexceptionrest_graphdbneographytransactionfailureexceptionrelationshipentityneo_j_ogmsdnwrappingneoserverbootstrappergraphrepositoryneo_j_graphdbnodeentityembeddedgraphdatabaseneo_jtemplate neo_j_spatialcypher_neo_jneo_j_cyphercypher_querynoe_jcypherneo_jrestclientpy_neoallshortestpathscypher_querieslinkuriousneoclipseexecutionresultbatch_importerwebadmingraphdatabasetimetreegraphawarerelatedtoviacypherqueryrecorelationshiptypespringrestgraphdatabaseflockdbneomodelneo_j_rbshortpathpersistable withindistancegraphdbneo_jneo_j_webadminmiddle_ground_betweenanormcypher materialised handaling hinted finds_nothingbulbsbulbflowrexprorexster cayleygremlintitandborient_dbaurelius tinkerpoptitan_cassandratitan_graph_dbtitan_graphorientdbtitan rexter enough_ram arangotinkerpop_gremlinpyorientlinkset arangodb_graphfoxxodocumentarangodborientjssails_orientdborientgraphexectedbaasbox spark_javarddrddsunpersist asigned aql fetchplanoriento bsonobjectpyspark_rddrddmatrixfactorizationmodelresultiterablemlibpushdownlineage transforamtionspark_rddpairrddreducebykeymappartitionstakeorderedrowmatrixpair_rddblockmanagerlinearregressionwithsgddstreamsencouter fieldtypes spark_dataframejavarddgroupbykeyorg_apache_spark_rddlabeledpointdatabricksaggregatebykeyjavasparkcontextsaveastextfilejavapairdstreamcombinebykeysparkcontext_textfilejavadstreammappartitionswithindexupdatestatebykeyreducebykeyandwindowrepartitioning -

Installation Guide Table of Contents

PUBLIC PowerBuilder 12.6 Document Version: 2.0 - 2014-10-27 Installation Guide Table of Contents 1 Installation Guide............................................................3 2 Installation Workflow.........................................................4 3 Planning Your Installation..................................................... 5 3.1 Installation Media Contents......................................................5 3.2 System Requirements......................................................... 5 3.3 Obtaining a License........................................................... 6 3.3.1 SySAM Troubleshooting.................................................7 3.4 Software Requirements........................................................ 9 4 Preinstallation Tasks........................................................ 12 5 Starting the Common Setup Program............................................13 6 Providing Basic Information...................................................15 7 Installing SQL Anywhere......................................................17 7.1 About SQL Anywhere......................................................... 18 8 Installing InfoMaker.........................................................19 8.1 InfoMaker Components....................................................... 20 9 Installing PowerBuilder ......................................................21 9.1 PowerBuilder Components.....................................................22 10 Completing the Setup Program................................................24 -

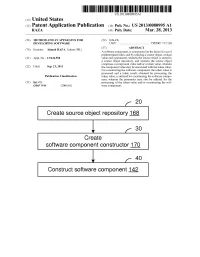

Create Source Object Repository 168

US 2013 0080995A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2013/0080995 A1 RAZA (43) Pub. Date: Mar. 28, 2013 (54) METHOD AND AN APPARATUS FOR (52) U.S. Cl. DEVELOPNG SOFTWARE USPC ........................................... 717/107; 717/120 (57) ABSTRACT (76) Inventor: Ahmad RAZA, Lahore (PK) A Software component, is constructed on the basis of a set of predetermined rules, and by utilizing a source object, a token (21) Appl. No.: 13/242.558 value and a parameter, wherein the Source object is stored in a source object repository, and wherein the source object comprises a component value and/or a token value, wherein (22) Filed: Sep. 23, 2011 the component value may be associated with the token value. For constructing the software component, the token value is processed and a token result, obtained by processing the Publication Classification token value, is utilized for constructing the software compo nent, wherein the parameter may also be utilized for the (51) Int. Cl. processing of the token value and/or constructing the Soft G06F 9/44 (2006.01) ware component. 2O Create Source object repository 168 Create Software component constructor 170 Construct software component 142 Patent Application Publication Mar. 28, 2013 Sheet 1 of 96 US 2013/0080995 A1 Create source object repository 168 Create Software component constructor 170 Construct software component 142 FIG. 1A Patent Application Publication Mar. 28, 2013 Sheet 2 of 96 US 2013/0080995 A1 108 110a 11 O Software Component 142 Select set of predetermined -

Project Summary Major Category Transportation Infrastructure Wards City Wide Version Name Main (Active)

Table of Contents Page Section A Summary of 5 – Year Capital Budget Summary of Capital Budget Expenditures and Funding Sources 1 Summary and Comparison of Capital Budget Expenditures by Major Categories 3 Section B 5-Year Capital Project Listing by Major Category 4 Section C 5-Year Summary of Capital Budget by Funding Source 12 Section D Summary of Growth vs. Maintenance Related Projects (Gross Expenditure Level) 31 Section E Summary of Growth vs. Maintenance Related Projects (Net Expenditure Level) 38 Section F Capital Project Summaries Agencies and Boards ...........……………...………………………………………… 45 Office of Community Development and Health ..............………………………… 66 Office of the Chief Administrative Officer ..............……………………………… 84 Office of the Chief Financial Officer ...........…………………………………….. 87 Office of the City Clerk ...........………………………………………………….... 113 Office of the City Engineer ...........……………………………………………….. 125 Office of the City Solicitor ............……………………………………………….... 328 2010 Recommended Capital Budget for Administrative Review 2012 Approved Capital Budget Section A: Summary of 5 – Year Capital Budget Summary of Capital Budget Expenditures and Funding Sources ($ 000's) for Budget Year 2012 (5-Year Capital Plan)*** Internal Pay As You Go Corporate Reserves External Sources Pay As You Go Pay As You Go Capital Development Infrastructure Recreation Pay As You Go Other Provincial Federal Fuel Tax ** Other Third-Party Year Operating Sewer Expenditure Charges Stimulus Funding Infrastructure Total Debt Reduction Reserves -

9397 Microway Update #24 Aprmay08.Indd

UPDATE April / May 2008 NEW! CONTENTS Functional Index page 22 DEVELOPER 3rdRail . 17 C++Builder 2007 . 16 Visual Studio 2008 Officially Launched! new technology for developing rich interactive Chart FX . 3 As most would already know by now, Microsoft applications for the Web). Take a look at CodeCharge Studio 4.0 . 9 the products under the Developer category CodeGear RAD Studio 2007. 16 “officially” launched Visual Studio 2008 in February. ComponentOne Studio Enterprise 2008 . 4 in this edition. DataWindow. NET 2.5 . 20 What is not so well known is that our MSDN Delphi/400 & Delphi/400 for PHP . 16 InstallShield 2008 Express . 14 customers have enjoyed access to the final release DB2, AS400 and Series-i products InstallShield 2008 . 11 of Visual Studio 2008 since November 2007, and MicroWay has products to assist with data JBuilder 2008. 17 JGear LiveSource. 17 have saved $000’s by ordering under a licensing replication, real-time XML translation and to make Keystone Training - .NET Complete . 2 scheme known as the “Open Business License”. integration and development faster for Windows LEADTOOLS Document Imaging Suite . 3 Nalpeiron Licensing Service . 24 If you don’t have an MSDN subscription, or are based developers & administrators working with NetAdvantage for .NET + WPF . 6 getting close to renewal time, you should check AS400/Series-i based data. See the Hit Ritmo and PrimalScript 2007 . 8 RadControls for ASP.NET . 8 out the benefits and huge savings on VS2008 and DBmoto products, as well as CodeGear’s new Ritmo/DB2 . 24 MSDN presented on page 7. MicroWay is the Delphi 400 in this edition. -

Delphi Is the Enterprise Solution for Euclid Technology

Success Story Delphi “Delphi helps Euclid Technology be first to market with Enterprise Solution on Windows Vista. ORGANIZATION ” – Charles Vinal, President and CEO, Euclid Technology Euclid Technology INTRodUCTION such as cross tabs and charting. ClearVantage uses the SQL Server 2005 database, and also ClearVantage from Euclid Technology is runs on SQL Server 2000 and Embarcadero’s an integrated CRM (customer relationship InterBase®. management), ERP (enterprise resource planning), eCommerce and Web Content Euclid has ported the ClearVantage enterprise Management solution built with Delphi. application (more than 480,000 lines of code, AppLICATION ClearVantage is designed for use by trade plus multiple 3rd party components) from Delphi • ClearVantage from Euclid associations and non-profits, and is currently 5 to Delphi 2007. The SOA and web architecture Technology – Integrated used by over 100 organizations ranging in size were ported from Delphi 7 as well, requiring no CRM, ERP, eCommerce and from 15 to 1000 employees. more than a recompile. The application now runs Web Content Management on Vista, has all of the glass features and dialogs, WHAT EUCLID BUILT WITH DELPHI an optional Office 2007 ribbon interface and also runs as it always has on XP. IDE OF CHOIce Features of the ClearVantage solution are • Delphi used by everyone in the organization – from Web Services are primarily wrapped in ISAPI the receptionist to membership management DLLs for ease of integration with other web CHALLENGes to the executive director. What’s more, the development applications. The ISAPI DLLs association or non-profit’s constituents use the connect to the program’s web services to get • Windows Vista enabling of websites that are powered by ClearVantage to data, and then return the data in the selected existing product purchase products, track orders, pay bills and format to the calling application – such as a • Competing against interact with organization. -

Ultimate++ Forum Something with U++

Subject: Which is the biggest drawback of U++ "unpopuliarity"? Posted by fudadmin on Wed, 07 Dec 2005 20:02:13 GMT View Forum Message <> Reply to Message It would be good to have this poll in "%" but I don't know howto... so, please write your "%"... Are there any other reasons? biggest drawback of U++(total votes: 38) Articles & Reviews3/(8%) Features2/(5%) Lack of documentation33/(87%) Subject: Re: Which is the biggest drawback of U++ "unpopuliarity"? Posted by Garry on Sun, 08 Jan 2006 15:29:55 GMT View Forum Message <> Reply to Message Personally I think the best way to improve "popularity" is what's happening now - this forum. Even without reams of documentation, a good forum is what's needed to help out newbies, like myself. I've followed the progress of UPP for quite some time, but it's only now since the forum got up and running, that I've gotten a bit more confidence in sticking more time and effort into doing something with U++. The original mailing list was far too daunting to try and look for information. Keep up the good work here. Magazine articles would certainly also raise the profile of the project too. It's unusual to see such a powerful and well developed tool have such a low media impact. It's nearly impossible to find any information out there on the web except for download sites which always feature the same description of the project. Anyway, hopefully the download figures are indicating a trend in the right direction.