Re:Marks Journal of Signum (ISSN 2310-3795)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ogham-Runes and El-Mushajjar

c L ite atu e Vo l x a t n t r n o . o R So . u P R e i t ed m he T a s . 1 1 87 " p r f ro y f r r , , r , THE OGHAM - RUNES AND EL - MUSHAJJAR A D STU Y . BY RICH A R D B URTO N F . , e ad J an uar 22 (R y , PART I . The O ham-Run es g . e n u IN tr ating this first portio of my s bj ect, the - I of i Ogham Runes , have made free use the mater als r John collected by Dr . Cha les Graves , Prof. Rhys , and other students, ending it with my own work in the Orkney Islands . i The Ogham character, the fair wr ting of ' Babel - loth ancient Irish literature , is called the , ’ Bethluis Bethlm snion e or , from its initial lett rs, like “ ” Gree co- oe Al hab e t a an d the Ph nician p , the Arabo “ ” Ab ad fl d H ebrew j . It may brie y be describe as f b ormed y straight or curved strokes , of various lengths , disposed either perpendicularly or obliquely to an angle of the substa nce upon which the letters n . were i cised , punched, or rubbed In monuments supposed to be more modern , the letters were traced , b T - N E E - A HE OGHAM RU S AND L M USH JJ A R . n not on the edge , but upon the face of the recipie t f n l o t sur ace ; the latter was origi al y wo d , s aves and tablets ; then stone, rude or worked ; and , lastly, metal , Th . -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

1 Settlement Patterns in Roman Galicia

Settlement Patterns in Roman Galicia: Late Iron Age – Second Century AD Jonathan Wynne Rees Thesis submitted in requirement of fulfilments for the degree of Ph.D. in Archaeology, at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London University of London 2012 1 I, Jonathan Wynne Rees confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract This thesis examines the changes which occurred in the cultural landscapes of northwest Iberia, between the end of the Iron Age and the consolidation of the region by both the native elite and imperial authorities during the early Roman empire. As a means to analyse the impact of Roman power on the native peoples of northwest Iberia five study areas in northern Portugal were chosen, which stretch from the mountainous region of Trás-os-Montes near the modern-day Spanish border, moving west to the Tâmega Valley and the Atlantic coastal area. The divergent physical environments, different social practices and political affinities which these diverse regions offer, coupled with differing levels of contact with the Roman world, form the basis for a comparative examination of the area. In seeking to analyse the transformations which took place between the Late pre-Roman Iron Age and the early Roman period historical, archaeological and anthropological approaches from within Iberian academia and beyond were analysed. From these debates, three key questions were formulated, focusing on -

Perjury and False Witness in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages

Perjury and False Witness in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages by Nicholas Brett Sivulka Wheeler A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Nicholas Brett Sivulka Wheeler 2018 Perjury and False Witness in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages Nicholas Brett Sivulka Wheeler Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto 2018 Abstract This dissertation, ‘Perjury and False Witness in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages’, investigates changing perceptions of perjury and false witness in the late antique and early medieval world. Focusing on primary sources from the Latin-speaking, western Roman empire and former empire, approximately between the late third and seventh centuries CE, this thesis proposes that perjury and false witness were transformed into criminal behaviours, grave sins, and canonical offences in Latin legal and religious writings of the period. Chapter 1, ‘Introduction: The Problem of Perjury’s Criminalization’, calls attention to anomalies in the history and historiography of the oath. Although the oath has been well studied, oath violations have not; moreover, important sources for medieval culture – Roman law and the Christian New Testament – were largely silent on the subject of perjury. For classicists in particular, perjury was not a crime, while oath violations remained largely peripheral to early Christian ethical discussions. Chapter 2, ‘Criminalization: Perjury and False Witness in Late Roman Law’, begins to explain how this situation changed by documenting early possible instances of penalization for perjury. Diverse sources such as Christian martyr acts, provincial law manuals, and select imperial ii and post-imperial legislation suggest that numerous cases of perjury were criminalized in practice. -

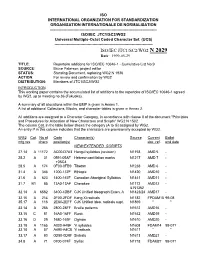

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2029 Date: 1999-05-29

ISO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR STANDARDIZATION ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE DE NORMALISATION --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2029 Date: 1999-05-29 TITLE: Repertoire additions for ISO/IEC 10646-1 - Cumulative List No.9 SOURCE: Bruce Paterson, project editor STATUS: Standing Document, replacing WG2 N 1936 ACTION: For review and confirmation by WG2 DISTRIBUTION: Members of JTC1/SC2/WG2 INTRODUCTION This working paper contains the accumulated list of additions to the repertoire of ISO/IEC 10646-1 agreed by WG2, up to meeting no.36 (Fukuoka). A summary of all allocations within the BMP is given in Annex 1. A list of additional Collections, Blocks, and character tables is given in Annex 2. All additions are assigned to a Character Category, in accordance with clause II of the document "Principles and Procedures for Allocation of New Characters and Scripts" WG2 N 1502. The column Cat. in the table below shows the category (A to G) assigned by WG2. An entry P in this column indicates that the characters are provisionally accepted by WG2. WG2 Cat. No of Code Character(s) Source Current Ballot mtg.res chars position(s) doc. ref. end date NEW/EXTENDED SCRIPTS 27.14 A 11172 AC00-D7A3 Hangul syllables (revision) N1158 AMD 5 - 28.2 A 31 0591-05AF Hebrew cantillation marks N1217 AMD 7 - +05C4 28.5 A 174 0F00-0FB9 Tibetan N1238 AMD 6 - 31.4 A 346 1200-137F Ethiopic N1420 AMD10 - 31.6 A 623 1400-167F Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics N1441 AMD11 - 31.7 B1 85 13A0-13AF Cherokee N1172 AMD12 - & N1362 32.14 A 6582 3400-4DBF CJK Unified Ideograph Exten. -

1 Working Draft for Supporting Blueberry Revision of XML

Working Draft for Supporting Blueberry Revision of XML Recommendation (1.0) with Particular Emphasis on Ethiopic Script and Writing System November 2001 This Version: http://www.digitaladdis.com/sk/ Ethiopics XML_Proposal_Version1.pdf Latest Ver.: http://www.digitaladdis.com/sk/ Ethiopics XML_Proposal_Version1.pdf Authors/Editors: Samuel Kinde Kassegne (Nanogen, UC San Diego, Engg Ext.) <[email protected]> Bibi Ephraim (Hewlett Packard) <[email protected]> Copyright ©2001, SKK, BE. Working Draft for Supporting Blueberry Revision of XML - Ethiopics Script 1 Abstract This document contains XML example codes, surveys and recommendations that support the need for Ethiopic script-based XML element type and attribute names in Amharic, Afaan Oromo, Tigrigna, Agewgna, Guragina, Hadiya, Harari, Sidama, Kembatigna and other Ethiopian languages that use Ethiopic script. Status of this Document This document is an initial working draft that is to be widely circulated for comment from the Ethiopic XML Interest Group and the wider public. The document is a work in progress. Table of Contents 1. Scope 2. Introduction 3. Objective 4. Review of Status of Native HTML and XML Applications in Ethiopic 4.1. Evolution of Ethiopic Content in HTML 4.2. Ethiopic and XML 5. Hybrid XML Document Markups in Ethiopic 5.1. Examples 5.2. Discussions 6. Fully-Native XML Document Markups in Ethiopic 6.1. Examples 6.2. Discussions 7. Conclusions and Recommendations 8. Appendix 9. References Working Draft for Supporting Blueberry Revision of XML - Ethiopics Script 2 1. Scope The work reported in this document contains XML example codes, surveys and recommendations that support the need for a revision of current XML standards to allow Ethiopic-based XML element type and attribute names in Amharic, Afaan Oromo, Tigrigna, Agewgna, Guragina, Hadiya, Harari, Sidama, Kembatigna and other Ethiopian languages that use Ethiopic script. -

Greek Alphabet ( ) Ελληνικ¿ Γρ¿Μματα

Greek alphabet and pronunciation 9/27/05 12:01 AM Writing systems: abjads | alphabets | syllabic alphabets | syllabaries | complex scripts undeciphered scripts | alternative scripts | your con-scripts | A-Z index Greek alphabet (ελληνικ¿ γρ¿μματα) Origin The Greek alphabet has been in continuous use for the past 2,750 years or so since about 750 BC. It was developed from the Canaanite/Phoenician alphabet and the order and names of the letters are derived from Phoenician. The original Canaanite meanings of the letter names was lost when the alphabet was adapted for Greek. For example, alpha comes for the Canaanite aleph (ox) and beta from beth (house). At first, there were a number of different versions of the alphabet used in various different Greek cities. These local alphabets, known as epichoric, can be divided into three groups: green, blue and red. The blue group developed into the modern Greek alphabet, while the red group developed into the Etruscan alphabet, other alphabets of ancient Italy and eventually the Latin alphabet. By the early 4th century BC, the epichoric alphabets were replaced by the eastern Ionic alphabet. The capital letters of the modern Greek alphabet are almost identical to those of the Ionic alphabet. The minuscule or lower case letters first appeared sometime after 800 AD and developed from the Byzantine minuscule script, which developed from cursive writing. Notable features Originally written horizontal lines either from right to left or alternating from right to left and left to right (boustophedon). Around 500 BC the direction of writing changed to horizontal lines running from left to right. -

De Episcopis Hispaniarum: Agents of Continuity in the Long Fifth Century

Université de Montréal De episcopis Hispaniarum: agents of continuity in the long fifth century accompagné de la prosopogaphie des évêques ibériques de 400–500 apr. J.-C., tirée de Purificación Ubric Rabaneda, “La Iglesia y los estados barbaros en la Hispania del siglo V (409–507), traduite par Fabian D. Zuk Département d’Histoire Faculté des Arts et Sciences Thèse présentée à la Faculté des études supérieures en vue de l’obtention du grade Maître ès Arts (M.A.) en histoire août 2015 © Fabian D. Zuk, 2015. ii Université de Montréal Faculté des etudes supérieures Ce mémoire intitule: De episcopis Hispaniarum: agents of continuity in the long fifth century présenté par Fabian D. Zuk A été évalué par un jury composé des personnes suivantes : Philippe Genequand, president–rapporteur Christian R. Raschle, directeur de recherche Gordon Blennemann, membre du jury iii In loving memory в пам'ять про бабусю of Ruby Zuk iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Résumé / Summary p. v A Note on Terminology p. vi Acknowledgements p. vii List of Figures p. ix Frequent ABBreviations p. x CHAPTER I : Introduction p. 1 CHAPTER II : Historical Context p. 23 CHAPTER III : The Origins of the Bishops p. 36 CHAPTER IV : Bishops as Spiritual Leaders p. 51 CHAPTER V : Bishops in the Secular Realm p. 64 CHAPTER VI : Regional Variation p. 89 CHAPTER VII : Bishops in the Face of Invasion : Conflict and Contenders p. 119 CHAPTER VIII : Retention of Romanitas p. 147 Annexe I: Prosopography of the IBerian Bishops 400–500 A.D. p. 161 Annexe II: Hydatius : An Exceptional Bishop at the End of the Earth p. -

K 03-UP-004 Insular Io02(A)

By Bernard Wailes TOP: Seventh century A.D., peoples of Ireland and Britain, with places and areas that are mentioned in the text. BOTTOM: The Ogham stone now in St. Declan’s Cathedral at Ardmore, County Waterford, Ireland. Ogham, or Ogam, was a form of cipher writing based on the Latin alphabet and preserving the earliest-known form of the Irish language. Most Ogham inscriptions are commemorative (e.g., de•fin•ing X son of Y) and occur on stone pillars (as here) or on boulders. They date probably from the fourth to seventh centuries A.D. who arrived in the fifth century, occupied the southeast. The British (p-Celtic speakers; see “Celtic Languages”) formed a (kel´tik) series of kingdoms down the western side of Britain and over- seas in Brittany. The q-Celtic speaking Irish were established not only in Ireland but also in northwest Britain, a fifth- THE CASE OF THE INSULAR CELTS century settlement that eventually expanded to become the kingdom of Scotland. (The term Scot was used interchange- ably with Irish for centuries, but was eventually used to describe only the Irish in northern Britain.) North and east of the Scots, the Picts occupied the rest of northern Britain. We know from written evidence that the Picts interacted extensively with their neighbors, but we know little of their n decades past, archaeologists several are spoken to this day. language, for they left no texts. After their incorporation into in search of clues to the ori- Moreover, since the seventh cen- the kingdom of Scotland in the ninth century, they appear to i gin of ethnic groups like the tury A.D. -

A STUDY of WRITING Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu /MAAM^MA

oi.uchicago.edu A STUDY OF WRITING oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu /MAAM^MA. A STUDY OF "*?• ,fii WRITING REVISED EDITION I. J. GELB Phoenix Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS oi.uchicago.edu This book is also available in a clothbound edition from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS TO THE MOKSTADS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada Copyright 1952 in the International Copyright Union. All rights reserved. Published 1952. Second Edition 1963. First Phoenix Impression 1963. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE HE book contains twelve chapters, but it can be broken up structurally into five parts. First, the place of writing among the various systems of human inter communication is discussed. This is followed by four Tchapters devoted to the descriptive and comparative treatment of the various types of writing in the world. The sixth chapter deals with the evolution of writing from the earliest stages of picture writing to a full alphabet. The next four chapters deal with general problems, such as the future of writing and the relationship of writing to speech, art, and religion. Of the two final chapters, one contains the first attempt to establish a full terminology of writing, the other an extensive bibliography. The aim of this study is to lay a foundation for a new science of writing which might be called grammatology. While the general histories of writing treat individual writings mainly from a descriptive-historical point of view, the new science attempts to establish general principles governing the use and evolution of writing on a comparative-typological basis. -

Lusitanian Amphorae: Production and Distribution

Lusitanian Amphorae: Production and Distribution ĞĚŝƚĞĚďLJ /ŶġƐsĂnjWŝŶƚŽ͕ZƵŝZŽďĞƌƚŽĚĞůŵĞŝĚĂ ĂŶĚƌĐŚĞƌDĂƌƟŶ ZŽŵĂŶĂŶĚ>ĂƚĞŶƟƋƵĞDĞĚŝƚĞƌƌĂŶĞĂŶWŽƩĞƌLJϭϬ 2016 Roman and Late Antique Mediterranean Pottery Archaeopress Series EDITORIAL BOARD (in alphabetical order) Series Editors Michel BONIFAY, Centre Camille Jullian, (Aix Marseille Univ, CNRS, MCC, CCJ, F-13000, Aix-en-Provence, France) Miguel Ángel CAU, Institució Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avançats (ICREA)/Equip de Recerca Arqueològica i Arqueomètrica, Universitat de Barcelona (ERAAUB) Paul REYNOLDS, Institució Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avançats (ICREA)/Equip de Recerca Arqueològica i Arqueomètrica, Universitat de Barcelona (ERAAUB) Honorary editor John HAYES, Institute of Archaeology, University of Oxford Associate editors Philip KENRICK, Institute of Archaeology, University of Oxford John LUND, The National Museum of Denmark, Denmark Scientific Committee for Pottery Xavier AQUILUÉ, Paul ARTHUR, Cécile BATIGNE, Moncef BEN MOUSSA, Darío BERNAL, Raymond BRULET, Claudio CAPELLI, Armand DESBAT, Nalan FIRAT, Michael G. FULFORD, Ioannis ILIOPOULOS, Sabine LADSTÄTTER, Fanette LAUBENHEIMER, Mark LAWALL, Sévérine LEMAÎTRE, Hassan LIMANE, Daniele MALFITANA, Archer MARTIN, Thierry MARTIN, Simonetta MENCHELLI, Henryk MEYZA, Giuseppe MONTANA, Rui MORAIS, Gloria OLCESE, Carlo PAVOLINI, Theodore PEÑA, Verena PERKO, Platon PETRIDIS, Dominique PIERI, Jeroen POBLOME, Natalia POULOU, Albert RIBERA, Lucien RIVET, Lucia SAGUI, Sara SANTORO, Anne SCHMITT, Gerwulf SCHNEIDER, Kathleen SLANE, Roberta TOMBER, Inês -

The Suevic Kingdom Why Gallaecia?

chapter 4 The Suevic Kingdom Why Gallaecia? Fernando López Sánchez The Sueves…(came to) hold the supremacy which the Vandals abandoned.1 Introduction: Towards a Re-evaluation of the Suevic Kingdom of Hispania During the reign of Rechiar (448–456) in the middle of the fifth century, the Sueves’ hegemony in Hispania seemed unassailable. Rechiar had inherited from his father, Rechila (438–448), a Suevic kingdom strong in Gallaecia and assertive across the Iberian Peninsula.2 By marrying a daughter of Theoderic I in 449, the new Suevic king won the support of the Visigothic rulers in Toulouse.3 As a Catholic, Rechiar managed to draw closer to the population of Hispania and also to Valentinian III, making himself, in a sense, a ‘modern’ monarch.4 In 453, he secured imperial backing through a pact with the imperial house of Ravenna.5 Confident in his power and prospects, Rechiar plundered Carthaginiensis and, finally, Tarraconensis, the last Spanish province under imperial control, following the deaths of Aëtius (454) and Valentinian III (455).6 1 Ubric (2004), 64. 2 For an analysis of Rechila’s ambitions and achievements: Pampliega (1998), 303–312. 3 Hyd. 132, pp. 98–99; Valverde (1999), 304. 4 Rechiar’s father, Rechila, died a pagan (gentilis), but Hydatius 129, pp. 98–99, describes Rechiar as catholicus at the time of his succession; see also Isidore of Seville, Historia Sueuorum 86–87, p. 301. Presumably, Rechila, his predecessor, Hermeric, and most of the Suevic aristocracy fol- lowed traditional German religious practices: Schäferdiek (1967), 108; García Moreno (1997), 200–201.