Maeve Brennan • “The Servants' Dance” • Lecture/Exam Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) Act, 1922

Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) Act, 1922 CONSTITUTION OF THE IRISH FREE STATE (SAORSTÁT EIREANN) ACT, 1922. AN ACT TO ENACT A CONSTITUTION FOR THE IRISH FREE STATE (SAORSTÁT EIREANN) AND FOR IMPLEMENTING THE TREATY BETWEEN GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND SIGNED AT LONDON ON THE 6TH DAY OF DECEMBER, 1921. DÁIL EIREANN sitting as a Constituent Assembly in this Provisional Parliament, acknowledging that all lawful authority comes from God to the people and in the confidence that the National life and unity of Ireland shall thus be restored, hereby proclaims the establishment of The Irish Free State (otherwise called Saorstát Eireann) and in the exercise of undoubted right, decrees and enacts as follows:— 1. The Constitution set forth in the First Schedule hereto annexed shall be the Constitution of The Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann). 2. The said Constitution shall be construed with reference to the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland set forth in the Second Schedule hereto annexed (hereinafter referred to as “the Scheduled Treaty”) which are hereby given the force of law, and if any provision of the said Constitution or of any amendment thereof or of any law made thereunder is in any respect repugnant to any of the provisions of the Scheduled Treaty, it shall, to the extent only of such repugnancy, be absolutely void and inoperative and the Parliament and the Executive Council of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) shall respectively pass such further legislation and do all such other things as may be necessary to implement the Scheduled Treaty. -

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor A Thesis in the Department of History Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts (History) at Concordia University Montréal, Québec, Canada March 2019 © Kyle McCreanor, 2019 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Kyle McCreanor Entitled: Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: _________________________________ Chair Dr. Andrew Ivaska _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Ted McCormick _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Cameron Watson _________________________________ Supervisor Dr. Gavin Foster Approved by _________________________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director _______________ 2019 _________________________________________ Dean of Faculty iii Abstract Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor This thesis examines the relationships between Irish and Basque nationalists and nationalisms from 1895 to 1939—a period of rapid, drastic change in both contexts. In the Basque Country, 1895 marked the birth of the Partido Nacionalista Vasco (Basque Nationalist Party), concurrent with the development of the cultural nationalist movement known as the ‘Gaelic revival’ in pre-revolutionary Ireland. In 1939, the Spanish Civil War ended with the destruction of the Spanish Second Republic, plunging Basque nationalism into decades of intense persecution. Conversely, at this same time, Irish nationalist aspirations were realized to an unprecedented degree during the ‘republicanization’ of the Irish Free State under Irish leader Éamon de Valera. -

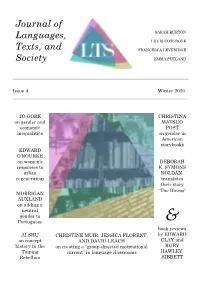

Journal of Languages, Texts, and Society

Journal of Languages, SARAH BURTON LOUIS COTGROVE Texts, and FRANCESCA LEVERIDGE Society EMMA PUTLAND Issue 4 Winter 2020 JO GORE CHRISTINA on gender and MATSUO economic POST inequalities on gender in American storybooks EDWARD O’ROURKE on women’s DEBORAH responses to K. SYMONS urban ROLDÁN regeneration translates their story “The Illness” MORRIGAN AUXLAND on adding a neutral gender to Portuguese & book reviews AI SHU CHRISTINE MUIR, JESSICA FLORENT, by EDWARD on concept AND DAVID LEACH CLAY and history in the on creating a “group-directed motivational RUBY Taiping current” in language classrooms HAWLEY- Rebellion SIBBETT Journal of Languages, Texts, and Society Issue 4 Winter 2020 License (open access): This is an open-access journal. Unless otherwise noted, all content in the journal is distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license. This license permits the use, re-distribution, reproduction, and adaptation of the material in any medium or format, under the following terms: (a) the original work is properly cited; (b) the material may not be used for commercial purposes; and (c) any use or adaptation of the materials must be distributed under the same terms as the original. For further details, please see the full license at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Acknowledgements The editors would like to thank everyone who has contributed to, produced, edited, and supported the making of Issue 4. We would also like to thank Louis Cotgrove for providing our -

Ireland and Irishness: the Contextuality of Postcolonial Identity

Ireland and Irishness: The Contextuality of Postcolonial Identity Kumar, M. S., & Scanlon, L. A. (2019). Ireland and Irishness: The Contextuality of Postcolonial Identity. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 109(1), 202-222. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2018.1507812 Published in: Annals of the Association of American Geographers Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2018 by American Association of Geographers. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:29. Sep. 2021 Ireland and Irishness: The Contextuality of Postcolonial Identity The porous boundaries of postcolonial studies are put to the test in examining the Irish question and its position in postcolonial studies. Scholars have explored Ireland through the themes of decolonization, diaspora, and religion, but we propose indigenous studies as a way forward to push the boundaries and apply an appropriate context to view the 1916 Commemorations, a likely focus of Irish Studies for years to come. -

When Art Becomes Political: an Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence History & Classics Undergraduate Theses History & Classics 12-15-2018 When Art Becomes Political: An Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011 Maura Wester Providence College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/history_undergrad_theses Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the European History Commons Wester, Maura, "When Art Becomes Political: An Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011" (2018). History & Classics Undergraduate Theses. 6. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/history_undergrad_theses/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History & Classics at DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in History & Classics Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. When Art Becomes Political: An Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011 by Maura Wester HIS 490 History Honors Thesis Department of History and Classics Providence College Fall 2018 For my Mom and Dad, who encouraged a love of history and showed me what it means to be Irish-American. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………… 1 Outbreak of The Troubles, First Murals CHAPTER ONE …………………………………………………………………….. 11 1981-1989: The Hunger Strike, Republican Growth and Resilience CHAPTER TWO ……………………………………………………………………. 24 1990-1998: Peace Process and Good Friday Agreement CHAPTER THREE ………………………………………………………………… 38 The 2000s/2010s: Murals Post-Peace Agreement CONCLUSION……………………………………………………………………… 59 BIBLIOGRAPHY …………………………………………………………………… 63 iv 1 INTRODUCTION For nearly thirty years in the late twentieth century, sectarian violence between Irish Catholics and Ulster Protestants plagued Northern Ireland. Referred to as “the Troubles,” the violence officially lasted from 1969, when British troops were deployed to the region, until 1998, when the peace agreement, the Good Friday Agreement, was signed. -

BRENNAN, MAEVE. Maeve Brennan Papers, 1948-1981

BRENNAN, MAEVE. Maeve Brennan papers, 1948-1981 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Brennan, Maeve. Title: Maeve Brennan papers, 1948-1981 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1142 Extent: 2.75 linear feet (6 boxes) and 1 oversized papers box (OP) Abstract: Papers of Irish American author Maeve Brennan including personal papers, writings by Brennan, writings by others, and printed material. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Related Materials in Other Repositories Robert Brennan and Maeve Brennan papers, University of Delaware Library, Special Collections Source Purchased from Glenn Horowitz Bookseller, 2010. One subsequent addition of a letter and clippings collected by Ray A. Roberts were purchased from Horowitz in 2011. Custodial History The Rose Library purchased this collection from book dealer Glenn Horowitz in 2010. The original owner bought it in the early 1970s as the unknown contents of a trunk sold at an auction of abandoned items from a storage facility in Wellfleet, Massachusetts. During the 1960s, Brennan spent her summers in the town. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Maeve Brennan papers, 1948-1981 Manuscript Collection No. 1142 Citation [after identification of item(s)], Maeve Brennan papers, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. -

And Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction

Date of most recent action: October 9, 2018 Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on their Destruction Done: Washington, London and Moscow April 10, 1972 Opened for signature: In accordance with Article XIV, paragraph 1, the Convention was open to all States for signature until its entry into force and any State which did not sign the Convention before its entry into force may accede to it at any time. Entry into force: March 26, 1975 In accordance with Article XIV, paragraph 2, the Convention is subject to ratification by signatory States. Article XIV, paragraph 3 provides for entry into force of the Convention after the deposit of instruments of ratification by twenty-two Governments, including the Governments designated as Depositaries of the Convention [Russian Federation, United Kingdom, United States]. For States whose instruments of ratification or accession are deposited subsequent to the entry into force of the Convention, it shall enter into force on the date of deposit of their instruments of ratification or accession. Note: This status list reflects actions at Washington only. Legend: (no mark) = ratification; A = acceptance; AA = approval; a = accession; d = succession; w = withdrawal or equivalent action Participant Signature Consent to be bound Other Action Notes Afghanistan April 10, 1972 Albania June 3, 1992 a Algeria September 28, 2001 a Andorra March 2, 2015 a Angola July 26, 2016 a Argentina August 7, 1972 November 27, 1979 -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: SLAVE SHIPS, SHAMROCKS, AND SHACKLES: TRANSATLANTIC CONNECTIONS IN BLACK AMERICAN AND NORTHERN IRISH WOMEN’S REVOLUTIONARY AUTO/BIOGRAPHICAL WRITING, 1960S-1990S Amy L. Washburn, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Dissertation directed by: Professor Deborah S. Rosenfelt Department of Women’s Studies This dissertation explores revolutionary women’s contributions to the anti-colonial civil rights movements of the United States and Northern Ireland from the late 1960s to the late 1990s. I connect the work of Black American and Northern Irish revolutionary women leaders/writers involved in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Black Panther Party (BPP), Black Liberation Army (BLA), the Republic for New Afrika (RNA), the Soledad Brothers’ Defense Committee, the Communist Party- USA (Che Lumumba Club), the Jericho Movement, People’s Democracy (PD), the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), the Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP), the National H-Block/ Armagh Committee, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA), Women Against Imperialism (WAI), and/or Sinn Féin (SF), among others by examining their leadership roles, individual voices, and cultural productions. This project analyses political communiqués/ petitions, news coverage, prison files, personal letters, poetry and short prose, and memoirs of revolutionary Black American and Northern Irish women, all of whom were targeted, arrested, and imprisoned for their political activities. I highlight the personal correspondence, auto/biographical narratives, and poetry of the following key leaders/writers: Angela Y. Davis and Bernadette Devlin McAliskey; Assata Shakur and Margaretta D’Arcy; Ericka Huggins and Roseleen Walsh; Afeni Shakur-Davis, Joan Bird, Safiya Bukhari, and Martina Anderson, Ella O’Dwyer, and Mairéad Farrell. -

Statute of Westminster, 1931. [22 GEO

Statute of Westminster, 1931. [22 GEO. 5. CH. 4.] ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS. A.D. 1931. Section. 1. Meaning of " Dominion" in this Act. Validity of laws made by Parliament of a Dominion. Power of Parliament of Dominion to legislate extra- territorially. 4. Parliament of United Kingdom not to legislate for Dominion except by consent. 5. Powers of Dominion Parliaments in relation to merchant shipping. 6. Powers of Dominion Parliaments in relation to Courts of Admiralty. 7. Saving for British North America Acts and application of the Act to Canada. 8. Saving for Constitution Acts of Australia and New Zealand. 9. Saving with respect to States of Australia. 10. Certain sections of Act not to apply to Australia, New Zealand or Newfoundland unless adopted. 11. Meaning of " Colony " in future Acts. 12. Short title. i [22 GEO. 5.] Statute of Westminster, 1931. [CH. 4.] CHAPTER 4. An Act to give effect to certain resolutions passed A.D. 1931. by Imperial Conferences held in the years 1926 and 1930. [11th December 1931.] HEREAS the delegates of His Majesty's Govern- W ments in the United Kingdom, the Dominion of Canada, the Commonwealth of Australia, the Dominion of New Zealand, the Union of South Africa, the Irish Free State and Newfoundland, at Imperial Conferences holden at Westminster in the years of our Lord nineteen hundred and twenty-six and nineteen hundred and thirty did concur in making the declarations and resolutions set forth in the Reports of the said Conferences : And whereas it is meet and proper to set out by way of preamble to this -

Reading the Irish Woman: Studies in Cultural Encounter and Exchange, 1714–1960

Reading the Irish Woman: Studies in Cultural Encounter and Exchange, 1714–1960 Meaney, Reading the Irish Woman.indd 1 15/07/2013 12:33:33 Reappraisals in Irish History Editors Enda Delaney (University of Edinburgh) Maria Luddy (University of Warwick) Reappraisals in Irish History offers new insights into Irish history, society and culture from 1750. Recognising the many methodologies that make up historical research, the series presents innovative and interdisciplinary work that is conceptual and interpretative, and expands and challenges the common understandings of the Irish past. It showcases new and exciting scholarship on subjects such as the history of gender, power, class, the body, landscape, memory and social and cultural change. It also reflects the diversity of Irish historical writing, since it includes titles that are empirically sophisticated together with conceptually driven synoptic studies. 1. Jonathan Jeffrey Wright, The ‘Natural Leaders’ and their World: Politics, Culture and Society in Belfast, c.1801–1832 Meaney, Reading the Irish Woman.indd 2 15/07/2013 12:33:33 Reading the Irish Woman Studies in Cultural Encounter and Exchange, 1714–1960 GerArdiNE MEANEY, MARY O’Dowd AND BerNAdeTTE WHelAN liVerPool UNIVersiTY Press Meaney, Reading the Irish Woman.indd 3 15/07/2013 12:33:33 reading the irish woman First published 2013 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2013 Gerardine Meaney, Mary O’Dowd and Bernadette Whelan The rights of Gerardine Meaney, Mary O’Dowd and Bernadette Whelan to be identified as the authors of this book have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

2014, Annual Report

ABBEY THE ABBEY at RE AMH A RCL A NN N A Ma INIS T RE A CH 2014 Annual Report 2014 ABBEY THEatRE AMHARCLANN NA MaINISTREACH 2014 Annual Report www.abbeytheatre.ie ABBEY THEatRE AMHARCLANN NA MAINISTREACH 2014 Annual Report Annual Report 2014 CONTENTS Chairman’s Welcome 6 Director's Report 10 Financial Overview 20 Our Impact 22 Artistic Programme 24 Awards 36 Literary Programme 38 Community & Education Programme 40 Talks 42 Artistic Development Programme 44 Abbey Theatre Archive 46 Celebrating 110 Years of the Abbey Theatre 47 Moments 48 Staff 62 Board of Directors 64 Supporters & Members 68 Gallery & Reviews 70 Financial Statements Extract 93 Annual Report 2014 As Ireland’s national theatre, our mission is to create a world class national theatre that actively engages with and reflects Irish society. The Abbey Theatre invests in, nurtures and promotes Irish theatre artists. We do this by placing the writer and theatre-maker at the heart of all that we do, commissioning and producing exciting new work and creating discourse and debate on the political, cultural and social issues of the day. Our aim is to present great theatre art in a national context so that the stories told on stage have a resonance with audiences and artists alike. The Abbey Theatre produces an ambitious annual programme of Irish and international theatre across our two stages and on tour in Ireland and internationally, having recently toured to Edinburgh, London, New York and Sydney. The Abbey Theatre is committed to building the Irish theatre repertoire, through commissioning and producing new Irish writing, and re-imagining national and international classics in collaboration with leading contemporary talent. -

Dept. of State, 1910

National Archives and Records Administration 8601 Adelphi Road College Park, Maryland 20740-6001 DEPARTMENT OF STATE 1910-1963 Central Decimal File Country Numbers Country Country Country Country Notes Number Number Number 1910-1949 1950-1959 1960-1963 Abaco Island 44e 41f 41e Abdul Quiri 46a 46c 46c Island Abyssinia 84 75 75 Discontinued 1936. Restored 1942. Acklin Island 44e 41f 41f Adaels 51v 51v 51v Aden (colony and 46a 46c 46c protectorate) Adrar 52c 52c 52c Afghanistan 90h 89 89 Africa 80 70 70 Aland Islands 60d 60e 60e Also see "Scandinavia." Alaska 11h Discontinued 1959. See 11. Albania 75 67 67 Alberta 42g Generally not used. See 42. Algeria 51r 51s 51s Alhucemas 52f 52f 52f America. Pan- 10 America American Samoa 11e 11e 11e Amhara 65d 77 Beginning 1936. For prior years see 65a, 65b, and 84. Discontinued 1960. See 75. Amsterdam 51x 51x 51x Island Andaman Islands 45a 46a 46a Andorra 50c 50c 50c Andros Island 44e 41f 41f Anglo-Egyptian 48z 45w Prior to May 1938, see 83. Sudan Angola 53m 53n 53n Anguilla 44k 41k Discontinued January 1958. See 41j. Annam 51g 51g 51g Annobon 52e 52e 52e Antarctic 02 02 Antigua 44k 41k Discontinued January 1958. See 41j. Country Country Country Country Notes Number Number Number 1910-1949 1950-1959 1960-1963 Arab 86 86 League/Arab States Arabia 90b 86 86 Arctic 01 Discontinued 1955. See 03. Arctic 03 03 Beginning 1955. Argentine 35 35 35 Republic/ Argentina Armenia 60j Discontinued. See 61. Aruba 56b 56b 56b Ascension Island 49f 47f 47f Asia 90 90 90 Austral Islands 51n 51p 51p Australasia and 51y Established 1960.