Outside the Lines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

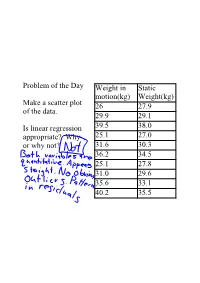

Problem of the Day Make a Scatter Plot of the Data. Is Linear Regression

Problem of the Day Weight in Static motion(kg) Weight(kg) Make a scatter plot 26 27.9 of the data. 29.9 29.1 Is linear regression 39.5 38.0 appropriate? Why 25.1 27.0 or why not? 31.6 30.3 36.2 34.5 25.1 27.8 31.0 29.6 35.6 33.1 40.2 35.5 Salary(in Problem of the Day Player Year millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 Is it appropriate to use George Foster 1982 2.0 linear regression Kirby Puckett 1990 3.0 to predict salary Jose Canseco 1991 4.7 from year? Roger Clemens 1996 5.3 Why or why not? Ken Griffey, Jr 1997 8.5 Albert Belle 1997 11.0 Pedro Martinez 1998 12.5 Mike Piazza 1999 12.5 Mo Vaughn 1999 13.3 Kevin Brown 1999 15.0 Carlos Delgado 2001 17.0 Alex Rodriguez 2001 22.0 Manny Ramirez 2004 22.5 Alex Rodriguez 2005 26.0 Chapter 10 ReExpressing Data: Get It Straight! Linear Regressioneasiest of methods, how can we make our data linear in appearance Can we reexpress data? Change functions or add a function? Can we think about data differently? What is the meaning of the yunits? Why do we need to reexpress? Methods to deal with data that we have learned 1. 2. Goal 1 making data symmetric Goal 2 make spreads more alike(centers are not necessarily alike), less spread out Goal 3(most used) make data appear more linear Goal 4(similar to Goal 3) make the data in a scatter plot more spread out Ladder of Powers(pg 227) Straightening is good, but limited multimodal data cannot be "straightened" multiple models is really the only way to deal with this data Things to Remember we want linear regression because it is easiest (curves are possible, but beyond the scope of our class) don't choose a model based on r or R2 don't go too far from the Ladder of Powers negative values or multimodal data are difficult to reexpress Salary(in Player Year Find an appropriate millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 linear model for the George Foster 1982 2.0 data. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Executive Report to the Board of Trustees • February 24, 2010

Executive Report to the Board of Trustees • February 24, 2010 CSM ALUM &GIANTS ANNOUNCER JON MILLER RECEIVES HALL OF FAME HONOR; VISITS CSM Major League Baseball Announcer and CSM Alum Jon Miller, who started his broadcasting career by announcing CSM baseball, football and basketball games, is headed to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. Also known as the “Voice of the Giants,” Miller is the 2010 recipient of the prestigious Ford C. Frick Award, presented annually to recognize excellence in baseball broadcasting. In addition to calling the play‐by‐play for the San Francisco Giants since 1997, Miller has also announced games for the Baltimore Orioles, Boston Red Sox, Texas Rangers and the Oakland A’s, and has been a regular on ESPN’s Sunday Night Baseball telecasts for 20 years. He will be inducted at the historic Cooperstown museum during the Baseball Hall of Fame’s induction ceremonies in July. John Miller & CSM broadcasting students As a broadcast veteran of 30 years Miller has received numerous awards, including the National Sportscaster of the Year from the National Sportscasters Association in 1998 and was inducted into the Hall of Fame of the National Sportswriters and Sportscasters Association of America. As described by the San Francisco Giants website, he is “noted for his eloquent game description, golden voice and marvelous sense of humor.” When Miller broadcasts games that include former CSM baseball players he often mentions CSM, the athletic program and his connection to the college. As a student at CSM in the late 1960’s, Miller was a broadcasting major who learned his craft by hosting a classical music program as well as announcing the college’s sports events on KCSM‐FM. -

Spring-2012.Pdf

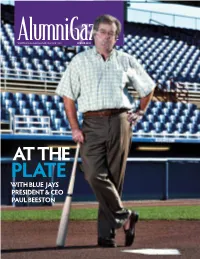

AlumniGazetteWESTERn’S ALUMNI MaGAZINE SINCE 1939 SPRING 2012 AT THE PL ATE WITH BLUE JAYS PRESIDENT & CEO PAUL BEESTON Buying?Buying? Renewing?Renewing? Refinancing?Refinancing? AlumniGazette Buying?Buying?Buying?Buying? Renewing?Renewing?Renewing?Renewing? Refinancing?Refinancing?Refinancing?Refinancing? CONTENTS ‘EVERY DAY IS SATURDAY’ 10 Cover story: At the plate with Blue Jays president & CEO Paul Beeston, BA’67, LLD’94 A DIPLOMAT FINDS HER 14 CALLING Sheila Siwela, BA’79, Zambia’s ambassador to the United States THE RIVER RUNS DEEP 16 Valiya Hamza, PhD’73, discovers underground river in Brazil THE WILL TO WIN 18 Silken Laumann, BA’89, reflects on her bronze medal win at the ’92 Olympics NEVER SaY NEVER 20 Tim Hudak, BA’90, and his path to Queen's Park 22 ROCK STAR CommittedCommitted to to Saving Saving YouYou ThousandsThousands Richard Léveillé, PhD’01, and NASA’s Mars CommittedCommittedCommitted to toto Saving SavingSaving You YouYou Thousands ThousandsThousands mission ofof Dollars Dollars on on Your Your NextNext MortgageMortgage ofofof Dollars DollarsDollars on onon Your YourYour Next NextNext Mortgage MortgageMortgage THE CIRQUE LIFE Alumni of Western University can SAVE on a mortgage 26 Craig Cohon, BA’85, brings Cirque du Soleil AlumniAlumniAlumni of of ofWestern Western Western UniversityUniversity University can can SAVE SAVE on onon a aa mortgage mortgagemortgage to Russia withAlumni the of best Western available University rates in can Canada SAVE while on a enjoyingmortgage withwithwith the the the best best best available available available ratesrates rates in in Canada Canada whilewhile while enjoying enjoyingenjoying outstandingwith the best service. available Whether rates in purchasing Canada while your enjoying first 20 outstandingoutstandingoutstanding service. -

Winter League AL Player List

American League Player List: 2020-21 Winter Game Pitchers 1988 IP ERA 1989 IP ERA 1990 IP ERA 1991 IP ERA 1 Dave Stewart R 276 3.23 258 3.32 267 2.56 226 5.18 2 Roger Clemens R 264 2.93 253 3.13 228 1.93 271 2.62 3 Mark Langston L 261 3.34 250 2.74 223 4.40 246 3.00 4 Bob Welch R 245 3.64 210 3.00 238 2.95 220 4.58 5 Jack Morris R 235 3.94 170 4.86 250 4.51 247 3.43 6 Mike Moore R 229 3.78 242 2.61 199 4.65 210 2.96 7 Greg Swindell L 242 3.20 184 3.37 215 4.40 238 3.48 8 Tom Candiotti R 217 3.28 206 3.10 202 3.65 238 2.65 9 Chuck Finley L 194 4.17 200 2.57 236 2.40 227 3.80 10 Mike Boddicker R 236 3.39 212 4.00 228 3.36 181 4.08 11 Bret Saberhagen R 261 3.80 262 2.16 135 3.27 196 3.07 12 Charlie Hough R 252 3.32 182 4.35 219 4.07 199 4.02 13 Nolan Ryan R 220 3.52 239 3.20 204 3.44 173 2.91 14 Frank Tanana L 203 4.21 224 3.58 176 5.31 217 3.77 15 Charlie Leibrandt L 243 3.19 161 5.14 162 3.16 230 3.49 16 Walt Terrell R 206 3.97 206 4.49 158 5.24 219 4.24 17 Chris Bosio R 182 3.36 235 2.95 133 4.00 205 3.25 18 Mark Gubicza R 270 2.70 255 3.04 94 4.50 133 5.68 19 Bud Black L 81 5.00 222 3.36 207 3.57 214 3.99 20 Allan Anderson L 202 2.45 197 3.80 189 4.53 134 4.96 21 Melido Perez R 197 3.79 183 5.01 197 4.61 136 3.12 22 Jimmy Key L 131 3.29 216 3.88 155 4.25 209 3.05 23 Kirk McCaskill R 146 4.31 212 2.93 174 3.25 178 4.26 24 Dave Stieb R 207 3.04 207 3.35 209 2.93 60 3.17 25 Bobby Witt R 174 3.92 194 5.14 222 3.36 89 6.09 26 Brian Holman R 100 3.23 191 3.67 190 4.03 195 3.69 27 Andy Hawkins R 218 3.35 208 4.80 158 5.37 90 5.52 28 Todd Stottlemyre -

Marquee Sports Network Announces Hiring of Jon Sciambi

MARQUEE SPORTS NETWORK ANNOUNCES JON SCIAMBI AS CHICAGO CUBS PLAY-BY-PLAY ANNOUNCER January 4, 2021 CHICAGO – Marquee Sports Network today announced the hiring of Jon “Boog” Sciambi as the Chicago Cubs television play-by-play announcer. Sciambi has served in numerous roles with ESPN since joining the network full- time in 2010, most prominently as the voice of ESPN Sunday Night Baseball for MLB on ESPN Radio, and as the regular play-by-play voice on Wednesday Night Baseball telecasts for ESPN since 2014. During his time at ESPN, Sciambi has contributed to ESPN Radio’s MLB World Series coverage as an on-site studio host, while providing post-game, on-field interviews for ESPN’s SportsCenter. He also has held play-by-play duties for both the College and Little League World Series. His time at the network dates to 2005, when he began doing play-by-play for select college basketball and MLB games, and he has continued in play-by-play for both sports during his tenure at ESPN. In addition to his play-by-play duties at Marquee, he will continue to serve as a multi- platform broadcaster for ESPN. Sciambi previously served as the lead play-by-play television announcer for the Atlanta Braves from 2007-2009 and as the radio voice of the Florida Marlins from 1997-2004. “We are excited to welcome Boog to the Marquee Network and the Cubs organization. We’re confident he’ll add to the incredible legacy of Cubs broadcasters and quickly become a trusted friend to our amazing fans,” said Crane Kenney, Chicago Cubs President of Business Operations. -

Weekly Notes 072817

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL WEEKLY NOTES FRIDAY, JULY 28, 2017 BLACKMON WORKING TOWARD HISTORIC SEASON On Sunday afternoon against the Pittsburgh Pirates at Coors Field, Colorado Rockies All-Star outfi elder Charlie Blackmon went 3-for-5 with a pair of runs scored and his 24th home run of the season. With the round-tripper, Blackmon recorded his 57th extra-base hit on the season, which include 20 doubles, 13 triples and his aforementioned 24 home runs. Pacing the Majors in triples, Blackmon trails only his teammate, All-Star Nolan Arenado for the most extra-base hits (60) in the Majors. Blackmon is looking to become the fi rst Major League player to log at least 20 doubles, 20 triples and 20 home runs in a single season since Curtis Granderson (38-23-23) and Jimmy Rollins (38-20-30) both accomplished the feat during the 2007 season. Since 1901, there have only been seven 20-20-20 players, including Granderson, Rollins, Hall of Famers George Brett (1979) and Willie Mays (1957), Jeff Heath (1941), Hall of Famer Jim Bottomley (1928) and Frank Schulte, who did so during his MVP-winning 1911 season. Charlie would become the fi rst Rockies player in franchise history to post such a season. If the season were to end today, Blackmon’s extra-base hit line (20-13-24) has only been replicated by 34 diff erent players in MLB history with Rollins’ 2007 season being the most recent. It is the fi rst stat line of its kind in Rockies franchise history. Hall of Famer Lou Gehrig is the only player in history to post such a line in four seasons (1927-28, 30-31). -

Baseball Broadcasting in the Digital Age

Baseball broadcasting in the digital age: The role of narrative storytelling Steven Henneberry CAPSTONE PROJECT University of Minnesota School of Journalism and Mass Communication June 29, 2016 Table of Contents About the Author………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………… 4 Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………… 5 Introduction/Background…………………………………………………………………… 6 Literature Review………………………………………………………………………………… 10 Primary Research Studies Study I: Content Analysis…………………………………………………………… 17 Study II: Broadcaster Interviews………………………………………………… 31 Study III: Baseball Fan Interviews……………………………………………… 48 Conclusion/Recommendations…………………………………………………………… 60 References………………………………………………………………………………………….. 65 Appendix (A) Study I: Broadcaster Biographies Vin Scully……………………………………………………………………… 69 Pat Hughes…………………………………………………………………… 72 Ron Coomer…………………………………………………………………… 72 Cory Provus…………………………………………………………………… 73 Dan Gladden…………………………………………………………………… 73 Jon Miller………………………………………………………………………… 74 (B) Study II: Broadcaster Interview Transcripts Pat Hughes…………………………………………………………………… 75 Cory Provus…………………………………………………………………… 82 Jon Miller……………………………………………………………………… 90 (C) Study III: Baseball Fan Interview Transcripts Donna McAllister……………………………………………………………… 108 Rick Moore……………………………………………………………………… 113 Rowdy Pyle……………………………………………………………………… 120 Sam Kraemer…………………………………………………………………… 121 Henneberry 2 About the Author The sound of Chicago Cubs baseball has been a near constant part of Steve Henneberry’s life. -

MLB Baseball 2021

MLB Season 2021 Things You Need to Know A Full Season… of Live Games! 56% Teams return to 162-game FANS Almost every National season with more than half game on ESPN, MLBN, 97% 1 of adults interested in MLB1 TBS & FS12 Your Local Team! Round the Bases Regional Sports Networks en Español bring home nearly every local 2 team game2 3WORLD FOX Deportes carries SERIES most FS1/FOX games FOX Sports RSN 519K 95% group rebrands +38% YOY ESPN Deportes features to Bally Sports on VIEWERS3 ESPN’s Sunday Night Baseball Opening Day! All Postseason games in Spanish-Language, including World Series4 Schedule subject to change. Source: (1) AdMall Pro AudienceSCAN, A18+ who are MLB Fans, 2021. (2) Based on last, full 162-game season in 2019. Nielsen NNTV Live Data Stream; 2Q17-1Q18; Total Day; Sports Events on Ad Cable and Broadcast. (3) FOX Sports Press Pass, 10/28/20. (4) Both MLBN games do not have a Spanish-Language Partner. Major League Baseball fans include over half (60%) who respond to TV ads, whether over-the-air, online, mobile or by tablet.* 66% 50% 52% 76% 83K 67% 70% 129% male A18-49 A25-54 A35+ median HHI any college own home more likely to stream sports MLB fans also watch these nets: Source: Scarborough USA+ 2020 Release 1 Total (Jan19-May20); A18+ who watch MLB Baseball on cable. Nets based on QTV ranking. *AdMall Pro AudienceSCAN, A18+ who are MLB fans & responded to a TV ad in the past year, 2020. MLB Season Baseball returns to a full 162-game season! ESPN’s Yankees-Nationals opener was the most-watched regular season game on any network since 2011 with 4M viewers.1 Opening Day will feature all 30 teams with a quadruple header of TOR-NYY, LAD-COL, NYM-WAS and HOU-OAK on ESPN. -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Thursday, April 1, 2021 * The Boston Globe With new faces, Red Sox begin quest to start anew, and put 2020 in the distance Alex Speier Opening Day typically offers the promise of renewal. Yet for the Red Sox, the first game of the 2021 season offers something more — the long-awaited opportunity for the franchise to begin officially distancing itself from the wreckage of the 2020 campaign. An active offseason represented a potential start to that undertaking. The team that is introduced prior to Thursday’s 2:10 p.m. contest against the Orioles will be drastically different from the one that last played in front of fans on Sept. 29, 2019 — a game punctuated by Mookie Betts diving across the plate in an extra- innings walkoff victory over Baltimore – and the one that opened last year’s fan-less, ill-fated, last-place slog through a compressed season. Many of the most recognizable faces in recent franchise history are now gone. The last time a home opener had fans in attendance, Mookie Betts, Jackie Bradley Jr., Andrew Benintendi, David Price, and Dustin Pedroia all collected their rings. Now, Betts and Price are Dodgers, Benintendi is a Royal, Bradley a Brewer, and Pedroia a retired dad. Still, while much has changed with those departures and the additions of players such as new leadoff hitter Kiké Hernández, outfielder Hunter Renfroe, starter Garrett Richards and late-innings contributor and Northeastern alum Adam Ottavino, there is some sense of reconnection to a time that predates the past 18 tumultuous months. -

Baseball All-Time Stars Rosters

BASEBALL ALL-TIME STARS ROSTERS (Boston-Milwaukee) ATLANTA Year Avg. HR CHICAGO Year Avg. HR CINCINNATI Year Avg. HR Hank Aaron 1959 .355 39 Ernie Banks 1958 .313 47 Ed Bailey 1956 .300 28 Joe Adcock 1956 .291 38 Phil Cavarretta 1945 .355 6 Johnny Bench 1970 .293 45 Felipe Alou 1966 .327 31 Kiki Cuyler 1930 .355 13 Dave Concepcion 1978 .301 6 Dave Bancroft 1925 .319 2 Jody Davis 1983 .271 24 Eric Davis 1987 .293 37 Wally Berger 1930 .310 38 Frank Demaree 1936 .350 16 Adam Dunn 2004 .266 46 Jeff Blauser 1997 .308 17 Shawon Dunston 1995 .296 14 George Foster 1977 .320 52 Rico Carty 1970 .366 25 Johnny Evers 1912 .341 1 Ken Griffey, Sr. 1976 .336 6 Hugh Duffy 1894 .440 18 Mark Grace 1995 .326 16 Ted Kluszewski 1954 .326 49 Darrell Evans 1973 .281 41 Gabby Hartnett 1930 .339 37 Barry Larkin 1996 .298 33 Rafael Furcal 2003 .292 15 Billy Herman 1936 .334 5 Ernie Lombardi 1938 .342 19 Ralph Garr 1974 .353 11 Johnny Kling 1903 .297 3 Lee May 1969 .278 38 Andruw Jones 2005 .263 51 Derrek Lee 2005 .335 46 Frank McCormick 1939 .332 18 Chipper Jones 1999 .319 45 Aramis Ramirez 2004 .318 36 Joe Morgan 1976 .320 27 Javier Lopez 2003 .328 43 Ryne Sandberg 1990 .306 40 Tony Perez 1970 .317 40 Eddie Mathews 1959 .306 46 Ron Santo 1964 .313 30 Brandon Phillips 2007 .288 30 Brian McCann 2006 .333 24 Hank Sauer 1954 .288 41 Vada Pinson 1963 .313 22 Fred McGriff 1994 .318 34 Sammy Sosa 2001 .328 64 Frank Robinson 1962 .342 39 Felix Millan 1970 .310 2 Riggs Stephenson 1929 .362 17 Pete Rose 1969 .348 16 Dale Murphy 1987 .295 44 Billy Williams 1970 .322 42 -

Sports Figures Price Guide

SPORTS FIGURES PRICE GUIDE All values listed are for Mint (white jersey) .......... 16.00- David Ortiz (white jersey). 22.00- Ching-Ming Wang ........ 15 Tracy McGrady (white jrsy) 12.00- Lamar Odom (purple jersey) 16.00 Patrick Ewing .......... $12 (blue jersey) .......... 110.00 figures still in the packaging. The Jim Thome (Phillies jersey) 12.00 (gray jersey). 40.00+ Kevin Youkilis (white jersey) 22 (blue jersey) ........... 22.00- (yellow jersey) ......... 25.00 (Blue Uniform) ......... $25 (blue jersey, snow). 350.00 package must have four perfect (Indians jersey) ........ 25.00 Scott Rolen (white jersey) .. 12.00 (grey jersey) ............ 20 Dirk Nowitzki (blue jersey) 15.00- Shaquille O’Neal (red jersey) 12.00 Spud Webb ............ $12 Stephen Davis (white jersey) 20.00 corners and the blister bubble 2003 SERIES 7 (gray jersey). 18.00 Barry Zito (white jersey) ..... .10 (white jersey) .......... 25.00- (black jersey) .......... 22.00 Larry Bird ............. $15 (70th Anniversary jersey) 75.00 cannot be creased, dented, or Jim Edmonds (Angels jersey) 20.00 2005 SERIES 13 (grey jersey ............... .12 Shaquille O’Neal (yellow jrsy) 15.00 2005 SERIES 9 Julius Erving ........... $15 Jeff Garcia damaged in any way. Troy Glaus (white sleeves) . 10.00 Moises Alou (Giants jersey) 15.00 MCFARLANE MLB 21 (purple jersey) ......... 25.00 Kobe Bryant (yellow jersey) 14.00 Elgin Baylor ............ $15 (white jsy/no stripe shoes) 15.00 (red sleeves) .......... 80.00+ Randy Johnson (Yankees jsy) 17.00 Jorge Posada NY Yankees $15.00 John Stockton (white jersey) 12.00 (purple jersey) ......... 30.00 George Gervin .......... $15 (whte jsy/ed stripe shoes) 22.00 Randy Johnson (white jersey) 10.00 Pedro Martinez (Mets jersey) 12.00 Daisuke Matsuzaka ....