Volumes 4 and 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020-2021 4Th Quarter Honor Roll Avon Lake High School NINTH

2020-2021 4th Quarter Honor Roll Avon Lake High School NINTH GRADE HIGH HONOR ROLL Maram Abuhamdeh, Caitlin Allen, Eilidh Allen, Anna Arnold, Maya Austerman, Vanessa Baker, Evan Balwani, Bilegtugs Bayarbadrakh, Tugsmergen Bayarbadrakh, Madeline Betz, Mary Bigenho, Michael Bodde, Owen Boolish, Fiona Bornhorst, Julia Breen, Haydn Brown, Mia Bucci, Kylie Bunn, Otto Burmeister, Micah Cabot, Cole Cartwright, Nolan Clancy, Felipe Covarrubias, Maria Drabkin, Elisabeth Dunleavy, Christina Elios, Sophia Elios, Anthony Ferrari, Jack Fink, Luke Florence, Ava Gabriel, Zachary Gacek, Lewis Gallagher, Caileen Gibbons, Anna Gill, Jacek Gomez, Patrick Gordillo, Ella Grode, Skylar Haibach, Jack Haley, Rylan Haley, Sloane Hall, Kayla Haskins, Grace He, Margaret Henry, Kamryn Hess, Emma Hill, Hattie Hobar, Hayden Hodge, Sophia Hoffman, Nicholas Homolka, David Ivan, Lila Jach, Zina Jalabi, Maxwell Keaton, Rachel Keim, Casey Kemer, Sophia Kerner, Logan King, Aubrey Kirk, Kennedy Koski, Kevin Kotyk, Cavin Kretchmar, Sydney Krieg, Abigail Krupitzer, Andrew Lamb, Ava Lamb, Anna LeHoty, Sabrina Marsala, Katherine Matovic, Casey Miller, Dylan Missal, Ella Monchein, Daphnie Norris, Sofia Ostrowsky, Elizabeth Paflas, Anikait Patel, Sarah Quayle, Spencer Reed, Kyle Ritter, Audrey Rodrigues, Nickolas Rudkin, Daniel Rudolph, Leah Sanitato, Ethan Sattler, Lauren Schaefer, Morgan Schum, Owen Sears, Brendan Seedhouse, Britta Sevcik, Avital Shmois, Rachael Simmerly, William Sindelar, Olivia Slivinski, Ella Smith, Claire Springer, Savannah Stobe, Marisa Summerfield, Faith -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Baby Girl Names Registered in 2018

Page 1 of 46 Baby Girl Names Registered in 2018 Frequency Name Frequency Name Frequency Name 8 Aadhya 1 Aayza 1 Adalaide 1 Aadi 1 Abaani 2 Adalee 1 Aaeesha 1 Abagale 1 Adaleia 1 Aafiyah 1 Abaigeal 1 Adaleigh 4 Aahana 1 Abayoo 1 Adalia 1 Aahna 2 Abbey 13 Adaline 1 Aaila 4 Abbie 1 Adallynn 3 Aaima 1 Abbigail 22 Adalyn 3 Aaira 17 Abby 1 Adalynd 1 Aaiza 1 Abbyanna 1 Adalyne 1 Aaliah 1 Abegail 19 Adalynn 1 Aalina 1 Abelaket 1 Adalynne 33 Aaliyah 2 Abella 1 Adan 1 Aaliyah-Jade 2 Abi 1 Adan-Rehman 1 Aalizah 1 Abiageal 1 Adara 1 Aalyiah 1 Abiela 3 Addalyn 1 Aamber 153 Abigail 2 Addalynn 1 Aamilah 1 Abigaille 1 Addalynne 1 Aamina 1 Abigail-Yonas 1 Addeline 1 Aaminah 3 Abigale 2 Addelynn 1 Aanvi 1 Abigayle 3 Addilyn 2 Aanya 1 Abiha 1 Addilynn 1 Aara 1 Abilene 66 Addison 1 Aaradhya 1 Abisha 3 Addisyn 1 Aaral 1 Abisola 1 Addy 1 Aaralyn 1 Abla 9 Addyson 1 Aaralynn 1 Abraj 1 Addyzen-Jerynne 1 Aarao 1 Abree 1 Adea 2 Aaravi 1 Abrianna 1 Adedoyin 1 Aarcy 4 Abrielle 1 Adela 2 Aaria 1 Abrienne 25 Adelaide 2 Aariah 1 Abril 1 Adelaya 1 Aarinya 1 Abrish 5 Adele 1 Aarmi 2 Absalat 1 Adeleine 2 Aarna 1 Abuk 1 Adelena 1 Aarnavi 1 Abyan 2 Adelin 1 Aaro 1 Acacia 5 Adelina 1 Aarohi 1 Acadia 35 Adeline 1 Aarshi 1 Acelee 1 Adéline 2 Aarushi 1 Acelyn 1 Adelita 1 Aarvi 2 Acelynn 1 Adeljine 8 Aarya 1 Aceshana 1 Adelle 2 Aaryahi 1 Achai 21 Adelyn 1 Aashvi 1 Achan 2 Adelyne 1 Aasiyah 1 Achankeng 12 Adelynn 1 Aavani 1 Achel 1 Aderinsola 1 Aaverie 1 Achok 1 Adetoni 4 Aavya 1 Achol 1 Adeyomola 1 Aayana 16 Ada 1 Adhel 2 Aayat 1 Adah 1 Adhvaytha 1 Aayath 1 Adahlia 1 Adilee 1 -

Place First Name Last Name Rail Trail 5K 3/21 Cherry Blossom 5K 4/17 Mt

Dannie Rail Trail 5K Cherry Blossom Mt. Holly Belmont Gastonia Benjamin Holy Angels Place First Name Last name 3/21 5K 4/17 Springfest 5/2 GOTR 5/9 Classic 5/23 Grizzlies 7/17 The Burn 9/7 10/17 10/31 Total 1 ROBIN LITTLEJOHN 94 85 93 85 85 92 94 85 713 2 JODI KINES 96 94 88 87 78 92 65 600 3 Lilly Gregory 91 81 67 67 72 80 87 54 599 4 OLIVIA COLE 89 83 54 74 65 69 83 69 586 5 Birgitt Zirden-Heulmanns 97 99 94 94 99 97 580 6 JENNIFER BOYD 93 80 87 91 70 421 7 DANIELLE SMALLWOOD 98 100 97 99 394 8 Deborah Inman 52 16 68 73 85 62 356 9 Kathleen DAvria 68 13 74 87 90 332 10 APRIL COLE 59 69 23 48 38 79 316 11 LAURA ARNOLD 97 97 96 290 12 APRIL BALLARD 95 97 94 286 13 Molly DAvria 97 94 91 282 14 Laura Gregory 83 76 5 56 60 280 15 Christi Eller 93 86 91 270 16 Stacy Dills 74 47 67 67 255 17 LUCINDA MARLOWE 78 83 86 247 18 Megan Yarbro 73 42 5 54 42 216 19 KATIE DANIS 100 100 200 20 Teresa Harrill 99 96 195 21 Katy Moss 93 96 189 22 Barbara Wheeler 94 92 186 23 Anna Colyer 90 95 185 24 Arlotte Lackey 87 91 178 25 Catherine Espey 90 87 177 26 Tyler White 89 79 168 27 Colleen Fancett 5 72 88 165 28 Paula Price 82 78 160 29 Jamie Brittain 86 72 158 30 Susan Simpson 75 77 152 31 KAREN DAVIS 70 81 151 32 Jennifer Sisk 69 80 149 33 Linda Hefner 78 5 61 144 34 TERESA YARBRO 67 71 5 143 35 Susan Heusser 65 70 135 36 BARBARA DEAN 72 61 133 37 RACHEL WHITAKER 58 73 131 38 Debbie Helton 5 53 66 124 39 CHRISTY HENDREN 54 70 124 40 Thelma Helms 46 77 123 41 Jamie Weaver 63 57 120 42 LAURA ISOM 57 61 118 43 Cherri Johnston 34 82 116 44 CINDY EASTERDAY 52 63 115 45 Lisa Marisiddaiah 69 38 107 Dannie Rail Trail 5K Cherry Blossom Mt. -

The Strokes Share New Episode of Pirate Radio Series Featuring Colin Jost and Gordon Raphael

THE STROKES SHARE NEW EPISODE OF PIRATE RADIO SERIES FEATURING COLIN JOST AND GORDON RAPHAEL “BAD DECISIONS” CLIMBING TOP 10 AT ALT RADIO FIRST ALBUM IN SEVEN YEARS THE NEW ABNORMAL OUT NOW VIA CULT/RCA RECORDS TO CRITICAL ACCLAIM July 23, 2020—Today, The Strokes share a new installment of their ongoing pirate radio series, “Five Guys Talking About Things They Know Nothing About”—watch it HERE. The new episode is the third installment of the show, and the first in a series in which the band will speak with the producers of their albums. The episode airing today features The Strokes in conversation with Gordon Raphael—who produced their debut EP The Modern Age, their first two LPs Is This It and Room On Fire and contributed to their third LP First Impressions Of Earth—as well as their longtime friend, SNL’s Colin Jost. The band’s new album The New Abnormal, their first in seven years, was released in April to widespread critical acclaim. The album’s lead single, “Bad Decisions,” is currently Top 10 at Alternative radio and still climbing, marking the band’s first Alternative Top 10 since 2006 and setting the record for the most time between Alternative Top 10 entries. Additionally, “Bad Decisions,” went #1 on AAA in April. Upon release, The New Abnormal debuted at #1 on Billboard’s Top Album Sales Chart and reached #8 on the Billboard 200, #1 Current Rock Album, #1 Top Current Album, #1 Current Alternative Album and #1 Vinyl Album. Of The New Abnormal, The Times of London praises “The Strokes give us their second masterpiece,” while The -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 133 MARCH 29TH, 2021 Copper has a new look! So does the rest of the PS Audio website, the result of countless hours of hard work. There's more functionality and easier access to articles, and additional developments will come. There will be some temporary glitches and some tweaks required – like high-end audio systems, magazines sometimes need tweaking too – but overall, we're excited to provide a better and more enjoyable reading experience. I now hand over the column to our esteemed Larry Schenbeck: Dear Copper Colleagues and Readers, Frank has graciously asked if I’d like to share a word or two about my intention to stop writing Too Much Tchaikovsky. So: thanks to everyone who read and enjoyed it – I wrote it for you. If you added comments occasionally, you made my day. I also wrote the column so I could keep learning, especially about emerging creatives and performers in classical music. Getting the chance to stumble upon something new and nourishing had sustained me in the academic world – it certainly wasn’t the money! – and I was grateful to continue that in Copper. So why stop? Because, as they say, there is a season. It has become considerably harder for me to stumble upon truly fresh sounds and then write freshly thereon. Here I am tempted to quote Douglas Adams or Satchel Paige, who both knew how to deliver an exit line. But I’ll just say (since Frank has promised to leave the light on), goodbye for now. The door is open, Larry, and we can’t thank you enough for your wonderful contributions. -

Jahrescharts 2020

JAHRESCHARTS 2020 TOP 200 TRACKS PEAK ARTIST TITLE LABEL/DISTRIBUTOR POSITION 01 The Strokes Bad Decisions RCA/Sony 01 02 The Killers My Own Soul's Warning Island/PIL/Universal 01 03 Tame Impala Lost In Yesterday Modular/Caroline/Universal 01 04 Drens Saditsfiction Recycled Earth/Zebralution 01 05 Fontaines D.C. A Hero's Death Partisan/[PIAS]/Rough Trade 01 06 Phoenix Identical Loyauté/Glassnote/AWAL 01 07 The Psychedelic Furs No-One Cooking Vinyl/The Orchard 01 08 Idles Mr. Motivator Partisan/[PIAS]/Rough Trade 01 09 Tame Impala Is It True Modular/Caroline/Universal 01 10 Giant Rooks Watershed IRRSINN/Vertigo Berlin/VEC/Universal 02 11 Grouplove Deleter Atlantic/WMI/Warner 03 12 Nada Surf Something I Should Do City Slang/Rough Trade 02 13 Weezer Hero Crush Music/Atlantic/WMI/Warner 01 14 Biffy Clyro Instant History 14th Floor/WMI/Warner 03 15 Rex Orange County Never Had The Balls Rex Orange County/Columbia/Sony 05 16 tomeque Immer Nur Tanzen (BelGium50-Remix) pop///tronica/Dig Dis/Timezone 03 17 Die Sterne Ft. Erobique & Kaiser Quartett Der Sommer In Die Stadt Wird Fahren [PIAS] Recordings/[PIAS]/Rough Trade 02 18 Sparkling We Don't Want It (Digitalism Remix) Vitamin A/Believe 04 19 The Kooks Something To Say Virgin/UMI/Universal 02 20 The Killers Caution Island/PIL/Universal 01 21 New Order Be A Rebel Mute/GoodToGo 02 22 Razorlight Burn, Camden, Burn Atlantic Culture/Believe 01 23 Roosevelt Sign Greco Roman/City Slang/Rough Trade 03 24 KennyHoopla How Will I Rest In Peace If I'm Buried By A Highway?// Mogul Vision/Arista/Sony 04 25 Two Door Cinema Club Tiptoes Prolifica/[PIAS]/Rough Trade 03 26 Morrissey Bobby, Don't You Think They Know? BMG Rights/ADA 03 27 Billy Talent Reckless Paradise Warner Canada/WMI/Warner 03 28 Turbostaat Stine [PIAS] Recordings/[PIAS]/Rough Trade 03 29 The Strokes Brooklyn Bridge To Chorus RCA/Sony 03 30 Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds Blue Moon Rising Sour Mash/375 Media 04 31 Giant Rooks Heat Up IRRSINN/Vertigo Berlin/VEC/Universal 01 32 Idles War Partisan/[PIAS]/Rough Trade 01 33 Gorillaz Ft. -

Place First Name Last Name Rail Trail 5K 3/21 Cherry Blossom 5K 4/17 Mt

Rail Trail 5K Cherry Blossom Mt. Holly Place First Name Last name 3/21 5K 4/17 Springfest 5/2 GOTR 5/9 Total Lilly Gregory 91 81 67 67 306 OLIVIA COLE 89 83 54 74 300 JODI KINES 96 94 88 278 ROBIN LITTLEJOHN 94 85 93 272 Birgitt Zirden-Heulmanns 97 99 196 Molly DAvria 97 94 191 Anna Colyer 90 95 185 Tyler White 89 79 168 Laura Gregory 83 76 5 164 APRIL COLE 59 69 23 151 Jennifer Sisk 69 80 149 TERESA YARBRO 67 71 5 143 Stacy Dills 74 47 121 Megan Yarbro 73 42 5 120 Andrea Shuler 59 42 101 Amy Edelstein 0 100 100 Jennifer Konkle 100 100 Georgia Toal 100 100 COURTNEY WEIMERT 100 100 Teresa Harrill 99 99 WHITNEY KIRBY 99 99 Elizabeth Roberts 99 99 Zoe Bumeter 98 98 Megan Dellinger 98 98 DANIELLE SMALLWOOD 98 98 Carrie Tucker 98 98 LAURA ARNOLD 97 97 Ellis Ku 97 97 Ella Barwick 96 96 Wendy McSwain 96 96 Karen Milling 96 96 Caroline Eason 95 95 Karen Gibson 95 95 JENNIFER TURNER 95 95 Barbara Wheeler 94 94 JENNIFER BOYD 93 93 Christi Eller 93 93 Katy Moss 93 93 ASHLEY BUSH 87 5 92 Kaylee Glover 92 92 Sandra Heafner 92 92 Paige Sisk 92 92 CHERYL SUTTON 92 92 Jackie Beam 91 91 Ainsley Harmon 91 91 Kathryn Lindquist 91 91 Hope Barwick 90 90 Catherine Espey 90 90 MARY HAMRICK 90 90 Kate Bookout 89 89 Carrie Lindquist 89 89 Andrea Bookout 88 88 ANGELA CHERKIS 88 88 Claire Germain 88 88 Emily Heil 87 87 Arlotte Lackey 87 87 Cameron Sealey 87 87 Jamie Brittain 86 86 Anna Grace Dixon 86 86 DEBBIE ROBINSON 86 86 Tameron Rushing 86 86 Christy Borman 85 85 JOYCE BROWN 85 85 Heather Day 85 85 DANNA ANTONIO LUNA 84 84 SUSAN HULL 84 84 Jennifer Stansell -

Baby Girl Names | Registered in 2019

Vital Statistics Baby2019 BabyGirl GirlsNames Names | Registered in 2019 From:Jan 01, 2019 To: Dec 31, 2019 First Name Frequency First Name Frequency First Name Frequency Aadhini 1 Aarnavi 1 Aadhirai 1 Aaro 1 Aadhya 2 Aarohi 2 Aadila 1 Aarora 1 Aadison 1 Aarushi 1 Aadroop 1 Aarya 3 Aadya 3 Aarza 2 Aafiya 1 Aashvee 1 Aaghnya 1 Aasiya 1 Aahana 2 Aasiyah 2 Aaila 1 Aasmi 1 Aaira 3 Aasmine 1 Aaleena 1 Aatmja 1 Aalia 1 Aatri 1 Aaliah 1 Aayah 2 Aalis 1 Aayara 1 Aaliya 1 Aayat 1 Aaliyah 17 Aayla 1 Aaliyah-Lynn 1 Aayna 1 Aalya 1 Aayra 2 Aamina 1 Aazeen 1 Aamna 1 Abagail 1 Aanaya 1 Abbey 4 Aaniya 1 Abbi 1 Aaniyah 1 Abbie 1 Aanya 3 Abbiejean 1 Aara 1 Abbigail 3 Aaradhya 1 Abbiteal 1 Aaradya 1 Abby 10 Aaraya 1 Abbygail 1 Aaria 2 Abdirashid 1 Aariya 1 Abeeha 1 Aariyah 1 Aberlene 1 Aarna 3 Abhideep 1 Abi 1 Abiah 1 10 Jun 2020 1 Abiegail 02:22:21 PM1 Abigael 1 Abigail 141 Abigale 1 1 10 Jun 2020 2 02:22:21 PM Baby Girl Names | Registered in 2019 First Name Frequency First Name Frequency Abigayle 1 Addalyn 4 Abihail 1 Addalynn 1 Abilene 2 Addasyn 1 Abina 1 Addelyn 1 Abisha 2 Addi 1 Ablakat 1 Addie 2 Aboni 1 Addilyn 3 Abrahana 1 Addilynn 2 Abreen 1 Addison 61 Abrielle 2 Addisyn 2 Absalat 1 Addley 1 Abuk 2 Addy 1 Abyan 1 Addyson 2 Abygale 1 Adedoyin 1 Acadia 1 Adeeva 1 Acelynn 1 Adeifeoluwa 1 Achai 1 Adela 1 Achan 1 Adélaïde 1 Achol 1 Adelaide 20 Ackley 1 Adelaine 1 Ada 23 Adelayne 1 Adabpreet 1 Adele 4 Adaeze 1 Adèle 2 Adah 1 Adeleigha 1 Adair 1 Adeleine 1 Adalee 1 Adelheid 1 Adalena 1 Adelia 3 Adaley 1 Adelina 2 Adalina 2 Adeline 40 Adalind 1 Adella -

Naughty and Nice List, 2020

North Pole Government NAUGHTY & NICE LIST 2020 NAUGHTY & NICE LIST Naughty and Nice List 2020 This is the Secretary’s This list relates to the people of the world’s performance for 2020 against the measures outlined Naughty and Nice in the Christmas Behaviour Statements. list to the Minister for Christmas Affairs In addition to providing an alphabetised list of all naughty and nice people for the year 2020, this for the financial year document contains details of how to rectify a ended 30 June 2020. naughty reputation. 2 | © Copyright North Pole Government 2020 christmasaffairs.com North Pole Government, Department of Christmas Affairs | Naughty and Nice List, 2020 Contents About this list 04 Official list (in alphabetical order) 05 Disputes 173 Rehabilitation 174 3 | © Copyright North Pole Government 2020 christmasaffairs.com North Pole Government, Department of Christmas Affairs | Naughty and Nice List, 2018-192020 About this list This list relates to the people of the world’s performance for 2020 against the measures outlined in the Christmas Behaviour Statements. In addition to providing an alphabetised list of all naughty and nice people for the 2020 financial year, this document contains details of how to rectify a naughty reputation. 4 | © Copyright North Pole Government 2020 christmasaffairs.com North Pole Government, Department of Christmas Affairs | Naughty and Nice List, 2020 Official list in alphabetical order A.J. Nice Abbott Nice Aaden Nice Abby Nice Aalani Naughty Abbygail Nice Aalia Naughty Abbygale Nice Aalis Nice Abdiel -

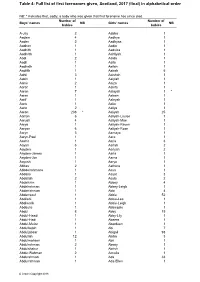

Table 4: Full List of First Forenames Given, Scotland, 2016 (Final) In

Table 4: Full list of first forenames given, Scotland, 2017 (final) in alphabetical order NB: * indicates that, sadly, a baby who was given that first forename has since died. Number of Number of Boys' names NB Girls' names NB babies babies A-Jay 2 Aabha 1 Aadam 4 Aadhya 1 Aaden 2 Aadhyaa 1 Aadhan 1 Aadia 1 Aadhith 1 Aadvika 1 Aadhrith 1 Aahliyah 1 Aadi 2 Aaida 1 Aadil 1 Aaila 1 Aadirath 1 Aailah 1 Aadrith 1 Aairah 5 Aahil 3 Aaishah 1 Aakin 1 Aaiylah 1 Aamir 2 Aaiza 1 Aaraf 1 Aakifa 1 Aaran 7 Aalayah 1 * Aarav 1 Aaleen 1 Aarif 1 Aaleyah 1 Aariv 1 Aalia 1 Aariz 2 Aaliya 1 Aaron 236 * Aaliyah 25 Aarron 6 Aaliyah-Louise 1 Aarush 4 Aaliyah-Mae 1 Aarya 1 Aaliyah-Raven 1 Aaryan 6 Aaliyah-Rose 1 Aaryn 3 Aamaya 1 Aaryn-Paul 1 Aara 1 Aashir 1 Aaria 3 Aayan 6 Aariah 2 Aayden 1 Aariyah 2 Aayden-James 1 Aarla 1 Aayden-Jon 1 Aarna 1 Aayush 1 Aarya 1 Abbas 2 Aathera 1 Abbdelrahmane 1 Aava 1 Abdalla 1 Aayat 3 Abdallah 2 Aayla 2 Abdelkrim 1 Abbey 4 Abdelrahman 1 Abbey-Leigh 1 Abderrahman 1 Abbi 4 Abderraouf 1 Abbie 52 Abdilahi 1 Abbie-Lee 1 Abdimalik 1 Abbie-Leigh 1 Abdoulie 1 Abbiegale 1 Abdul 8 Abby 19 Abdul-Haadi 1 Abby-Lily 1 Abdul-Hadi 1 Abeera 1 Abdul-Muizz 1 Aberdeen 1 Abdulfattah 1 Abi 7 Abduljabaar 1 Abigail 93 Abdullah 12 Abiha 3 Abdulmohsen 1 Abii 1 Abdulrahman 2 Abony 1 Abdulshakur 1 Abrish 1 Abdur-Rahman 2 Accalia 1 Abdurahman 1 Ada 33 Abdurrahman 1 Ada-Ellen 1 © Crown Copyright 2018 Table 4 (continued) NB: * indicates that, sadly, a baby who was given that first forename has since died Number of Number of Boys' names NB Girls' names NB -

Baby Girl Names Registered in 2012

Page 1 of 49 Baby Girl Names Registered in 2012 # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names 1 Aadhira 1 Abbey-Gail 1 Adaeze 3 Aadhya 1 Abbi 2 Adah 1 Aadya 1 Abbie 1 Adaira 1 Aahliah 11 Abbigail 1 Adaisa 1 Aahna 1 Abbigaile 1 Adalayde 1 Aaira 2 Abbigale 3 Adalee 1 Aaiza 1 Abbigayle 1 Adaleigh 1 Aalaa 1 Abbilene 2 Adalia 1 Aaleah 1 Abbrianna 1 Adalie 1 Aaleya 20 Abby 1 Adalina 1 Aalia 8 Abbygail 1 Adalind 1 Aaliah 1 Abbygail-Claire 2 Adaline 33 Aaliyah 1 Abbygaile 8 Adalyn 1 Aaliyah-Faith 3 Abbygale 1 Adalyne 1 Aaliyah-noor 1 Abbygayle 10 Adalynn 1 Aamina 1 Abby-lynn 1 Adanaya 1 Aaminah 1 Abebaye 2 Adara 1 Aaneya 2 Abeeha 1 Adau 1 Aangi 1 Abeer 2 Adaya 1 Aaniya 2 Abeera 1 Adayah 2 Aanya 1 Abegail 1 Addaline 3 Aaralyn 1 Abella 1 Addalyn 2 Aaria 1 Abem 1 Addalynn 3 Aarna 1 Abeni 1 Addeline 1 Aarohi 2 Abheri 1 Addelynn 1 Aarolyn 1 Abida 3 Addie 1 Aarvi 1 Abidaille 1 Addie-Mae 2 Aarya 1 Abigael 3 Addilyn 1 Aaryana 159 Abigail 2 Addilynn 1 Aasha 1 Abigaile 1 Addi-Lynne 2 Aashi 3 Abigale 78 Addison 1 Aashka 1 Abigayl 13 Addisyn 1 Aashna 2 Abigayle 1 Addley 1 Aasiyah 1 Abijot 1 Addy 1 Aauriah 1 Abilleh 9 Addyson 1 Aavya 1 Abinoor 1 Adedamisola 1 Aayah 2 Abrianna 1 Adeena 1 Aayana 2 Abrielle 1 Adela 1 Aayat 2 Abuk 1 Adelade 2 Aayla 1 Abyan 1 Adelae 1 Aayushi 3 Abygail 14 Adelaide 1 Ababya 2 Abygale 1 Adelaide-Lucille 1 Abagail 1 Acacia 2 Adelaine 1 Abagayle 1 Acasia 17 Adele 1 Abaigael 2 Acelyn 1 Adeleah 1 Abba 1 Achan 1 Adelee 1 Abbagail 2 Achol 1 Adeleigh 1 Abbegail 1 Achsa 1 Adeleine 12 Abbey 11 Ada 2 Adelia Page 2 of 49 Baby Girl