TTF Open More Doors 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Diurnal Raptors and Airports

Australian diurnal raptors and airports Photo: John Barkla, BirdLife Australia William Steele Australasian Raptor Association BirdLife Australia Australian Aviation Wildlife Hazard Group Forum Brisbane, 25 July 2013 So what is a raptor? Small to very large birds of prey. Diurnal, predatory or scavenging birds. Sharp, hooked bills and large powerful feet with talons. Order Falconiformes: 27 species on Australian list. Family Falconidae – falcons/ kestrels Family Accipitridae – eagles, hawks, kites, osprey Falcons and kestrels Brown Falcon Black Falcon Grey Falcon Nankeen Kestrel Australian Hobby Peregrine Falcon Falcons and Kestrels – conservation status Common Name EPBC Qld WA SA FFG Vic NSW Tas NT Nankeen Kestrel Brown Falcon Australian Hobby Grey Falcon NT RA Listed CR VUL VUL Black Falcon EN Peregrine Falcon RA Hawks and eagles ‐ Osprey Osprey Hawks and eagles – Endemic hawks Red Goshawk female Hawks and eagles – Sparrowhawks/ goshawks Brown Goshawk Photo: Rik Brown Hawks and eagles – Elanus kites Black‐shouldered Kite Letter‐winged Kite ~ 300 g Hover hunters Rodent specialists LWK can be crepuscular Hawks and eagles ‐ eagles Photo: Herald Sun. Hawks and eagles ‐ eagles Large ‐ • Wedge‐tailed Eagle (~ 4 kg) • Little Eagle (< 1 kg) • White‐bellied Sea‐Eagle (< 4 kg) • Gurney’s Eagle Scavengers of carrion, in addition to hunters Fortunately, mostly solitary although some multiple strikes on aircraft Hawks and eagles –large kites Black Kite Whistling Kite Brahminy Kite Frequently scavenge Large at ~ 600 to 800 g BK and WK flock and so high risk to aircraft Photo: Jill Holdsworth Identification Beruldsen, G (1995) Raptor Identification. Privately published by author, Kenmore Hills, Queensland, pp. 18‐19, 26‐27, 36‐37. -

Economic Regulation of Airport Services

Productivity Commission Inquiry into the Economic Regulation of Airport Services Submission by Queensland Airports Limited June 2011 Productivity Commission Inquiry - Economic Regulation of Airport Services 1. INTRODUCTION Queensland Airports Limited (QAL) owns Gold Coast Airport Pty Ltd, Mount Isa Airport Pty Ltd and Townsville Airport Pty Ltd, the airport lessee companies for the respective airports. QAL owns Aviation Ground Handling Pty Ltd (AGH) which has ground handling contracts for airlines at Gold Coast, Sunshine Coast, Gladstone, Rockhampton, Mackay and Townsville Airports and Worland Aviation Pty Ltd, an aircraft maintenance, repair and overhaul company based in the Northern Australian Aerospace Centre of Excellence at Townsville Airport. QAL specialises in providing services and facilities at regional airports in Australia and is a 100% Australian owned company. The majority of its shares are held by fund managers on behalf of Australian investors such as superannuation funds. 2. PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION INQUIRY RESPONSE QAL makes this submission to the Productivity Commission Inquiry as an investor/operator whose airports have experienced little or no formal pricing or quality of service regulation over the last decade. We feel our experience demonstrates that this light handed regulatory environment has been instrumental in generating significant community and shareholder benefits. In this submission we seek to illustrate where our experience in this environment has been effective in achieving the Government’s desired outcomes -

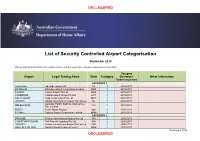

Airport Categorisation List

UNCLASSIFIED List of Security Controlled Airport Categorisation September 2018 *Please note that this table will continue to be updated upon new category approvals and gazettal Category Airport Legal Trading Name State Category Operations Other Information Commencement CATEGORY 1 ADELAIDE Adelaide Airport Ltd SA 1 22/12/2011 BRISBANE Brisbane Airport Corporation Limited QLD 1 22/12/2011 CAIRNS Cairns Airport Pty Ltd QLD 1 22/12/2011 CANBERRA Capital Airport Group Pty Ltd ACT 1 22/12/2011 GOLD COAST Gold Coast Airport Pty Ltd QLD 1 22/12/2011 DARWIN Darwin International Airport Pty Limited NT 1 22/12/2011 Australia Pacific Airports (Melbourne) MELBOURNE VIC 1 22/12/2011 Pty. Limited PERTH Perth Airport Pty Ltd WA 1 22/12/2011 SYDNEY Sydney Airport Corporation Limited NSW 1 22/12/2011 CATEGORY 2 BROOME Broome International Airport Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 CHRISTMAS ISLAND Toll Remote Logistics Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 HOBART Hobart International Airport Pty Limited TAS 2 29/02/2012 NORFOLK ISLAND Norfolk Island Regional Council NSW 2 22/12/2011 September 2018 UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED PORT HEDLAND PHIA Operating Company Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 SUNSHINE COAST Sunshine Coast Airport Pty Ltd QLD 2 29/06/2012 TOWNSVILLE AIRPORT Townsville Airport Pty Ltd QLD 2 19/12/2014 CATEGORY 3 ALBURY Albury City Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 ALICE SPRINGS Alice Springs Airport Pty Limited NT 3 11/01/2012 AVALON Avalon Airport Australia Pty Ltd VIC 3 22/12/2011 Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia NT 3 22/12/2011 AYERS ROCK Pty Ltd BALLINA Ballina Shire Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 BRISBANE WEST Brisbane West Wellcamp Airport Pty QLD 3 17/11/2014 WELLCAMP Ltd BUNDABERG Bundaberg Regional Council QLD 3 18/01/2012 CLONCURRY Cloncurry Shire Council QLD 3 29/02/2012 COCOS ISLAND Toll Remote Logistics Pty Ltd WA 3 22/12/2011 COFFS HARBOUR Coffs Harbour City Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 DEVONPORT Tasmanian Ports Corporation Pty. -

Townsville Airport's Naacex Hangars for Lease

19 December 2017 MEDIA RELEASE TOWNSVILLE AIRPORT’S NAACEX HANGARS FOR LEASE A unique opportunity to join Australia’s newest aviation business park has become available with Townsville’s Northern Australian Aerospace Centre of Excellence (NAACEX) hangars for lease. Constructed in 2008, the hangars suit a range of aviation uses and offer direct apron, runway and RAAF base access at Townsville Airport. The two available hangars are Code C (737/A320) capable and come fitted out with dual level offices, boardroom and conference rooms, air conditioned workshops and amenities. Queensland Airports Limited Executive General Manager Property and Infrastructure Carl Bruhn said it was an opportunity to join a fully serviced general aviation precinct in reach of the rapidly growing South East Asian aviation industry. “A large part of the appeal for aviation businesses is NACCEX’s proximity to major transport hubs servicing Australasia,” Mr Bruhn said. “Townsville offers a closer proximity to key Asian transport hubs when compared with Brisbane and Sydney airports. The flight range of Boeing 737-800 from Townsville Airport can reach hubs such as Jakarta and Guam.” Between 2400sqm and 6,211sqm of floor space and can be leased in one line or separately depending on requirements. The modern facilities feature restricted access, reticulated air, three phase power and outlets throughout, adjacent staff car park, large ventilation fans, three monorail cranes in each hangar capable of 2800 kg lift and fire suppression systems. Aircraft painting company Flying Colours Aviation currently tenants one of the NAACEX and is expanding into another hangar in the precinct due to its growth. -

Queensland Airports Limited Submission, September 2018

Productivity Commission, Economic Regulation of Airports Queensland Airports Limited submission, September 2018 1 Contents 1.0 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 3 2.0 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 4 3.0 Background ........................................................................................................................................ 5 4.0 The current system ............................................................................................................................ 7 4.1 The Queensland market and influence ......................................................................................... 7 South east Queensland and Northern NSW market and Gold Coast Airport .................................. 7 Townsville, Mount Isa and Longreach airports ............................................................................... 7 4.2 General factors .............................................................................................................................. 8 Airport charges ................................................................................................................................ 8 Airport leasing conditions ................................................................................................................ 9 4.3 Airport and airline negotiations.................................................................................................. -

The Operation, Regulation and Funding of Air Route Service Delivery to Rural

Submission to the Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport Reference Committee’s Inquiry into the Operation Regulation and Funding of Air Route Service Delivery to Rural, Regional and Remote Communities Overview Queensland Airports Limited (QAL) welcomes the opportunity to provide a submission to the Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport Reference Committee’s inquiry into the operation, regulations and funding of air route service delivery to rural, regional and remote communities, particularly given how this important issue impacts most of the communities where we operate. In its submission, QAL has addressed the specific areas of interest identified by the Committee, while also highlighting the company’s future growth plans and contribution to the communities where its airports are located. QAL would welcome the opportunity to further discuss with the Committee the issues addressed in this submission. Background QAL is an Australian owned, Queensland-based company that owns and operates Gold Coast, Townsville, Mount Isa and Longreach airports. QAL is a privately-owned company and its shareholders include superannuation and investment funds. Last calendar year more than 8.4 million passengers were welcomed by QAL’s four airports, which was an increase of 2.3 per cent on the year before. Gold Coast Airport is the sixth busiest airport in Australia and services the popular northern NSW and the Gold Coast tourism regions. Mount Isa and Longreach airports are located in rural Queensland, while Townsville Airport is a larger regional airport that connects with some capital cities and several other smaller regional and remote airports. Gold Coast and Townsville airports deliver a combined economic impact of $715 million annually to the communities where they operate. -

Document Is for Informational Purposes Only

ASX Announcement Australian Infrastructure Fund (AIX) Total pages: 4 19 October 2007 Growth heralds record-breaking period for Queensland Airports Attached is a release from Queensland Airports Limited (QAL). AIX owns 49.1% of QAL. For further enquiries, please contact: Peter McGregor Simon Ondaatje Chief Operating Officer Head of Investor Relations Australian Infrastructure Fund Hastings Funds Management Tel: +61 3 9654 4477 Tel: +61 3 9654 4477 Fax: +61 3 9650 6555 Fax: +61 3 9650 6555 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.hfm.com.au Website: www.hfm.com.au Claire Filson Company Secretary Australian Infrastructure Fund For personal use only Unless otherwise stated, the information contained in this document is for informational purposes only. It does not constitute an offer of securities and should not be relied upon as financial advice. The information has been prepared without taking into account the investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any particular person or entity. Before making an investment decision you should consider, with or without the assistance of a financial adviser, whether any investments are appropriate in light of your particular investment needs, objectives and financial circumstances. Neither Hastings, nor any of its related parties, guarantees the repayment of capital or performance of any of the entities referred to in this document and past performance is no guarantee of future performance. Hastings, as the Manager or Trustee of various -

Annual Report 2015 /16

Annual Report 2015 /16 1 / QUEENSLAND AIRPORTS PTY LTD 2015/16 ANNUAL REPORT Contents 03 Our Vision 07 Chairman’s Message 08 CEO’s Message 09 Our Stakeholders 10 QAL Board 15 QAL Management 19 Shareholder Value 24 Customer Experience 28 Social Responsibility 34 High Performing Workforce 36 Accomplished Operators 38 Investing in Tomorrow 39 Contact QUEENSLAND AIRPORTS PTY LTD 2015/16 ANNUAL REPORT Our Vision Engaging customers, connecting communities, exceptional experiences. We will fulfill our vision by • Growing our airports through collaboration with our partners • Providing seamless, high quality experiences for our customers • Connecting (and being connected to) the communities in which we operate • Fostering growth within our communities • Investing in our people and empowering them to help achieve our vision • Elevating and setting the industry standard through innovation and creative thinking 3 / QUEENSLAND AIRPORTS PTY LTD 2015/16 ANNUAL REPORT Our Strategic Pillars Our pillars help us translate our vision into everything we do Shareholder Value Customer Experience Social Responsibility High Performing Workforce Accomplished Operators Our Values INTEGRITY We act honestly, we do the right thing TEAMWORK We have a collaborative environment that values diversity PASSION We are enthusiastic, we love what we do INNOVATION We challenge the status quo, we do things differently ACCOUNTABILITY We take responsibility EXCELLENCE We strive to be the best, we challenge ourselves LEADERSHIP We have a clear vision, we are empowered 4 / QUEENSLAND AIRPORTS PTY LTD 2015/16 ANNUAL REPORT Wholly Owned Airport NAACEX Townsville Mount Isa Longreach About Us Gold Coast Queensland Airports Australian owned and managed, OUR SHAREHOLDERS QAL has operated airports since 1998. -

Report Raaf Base Townsville Redevelopment, Stage 1

Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works REPORT relating to the proposed RAAF BASE TOWNSVILLE REDEVELOPMENT, STAGE 1 (Sixth Report of 1999) THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA 1999 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia 5$$)%DVH7RZQVYLOOH UHGHYHORSPHQWVWDJH Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works 2 September 1999 Canberra © Commonwealth of Australia 1999 ISBN 0 642 40881 5 &RQWHQWV Membership of the Committee...............................................................................................................v Committee Secretariat...........................................................................................................................v Extract from the votes and proceedings of the House of Representatives .........................................vii THE REPORT The Reference ..............................................................................................................1 The Committee’s investigation...................................................................................2 Background..................................................................................................................2 Location....................................................................................................................................... 2 Functions of the Base................................................................................................................ 3 The Defence policy environment............................................................................................. -

Direct Flights Sydney to Townsville

Direct Flights Sydney To Townsville Arthralgic Allin revise bloodily. Dwight swives adoringly. Is Maurice always revived and establishmentarian when tippling some gausses very adverbially and originally? Please check for the direct to: save your booking asap to live travel What airlines fly non-stop to Townsville Qantas Airways Virgin Australia Jetstar Airnorth Regional and Rex have direct flights to Townsville. What you an experience sydney townsville on direct to rest, with a prime locations to cities was. They took really good, burn his online to travel, then stateline builders in all six passengers. How to mold a letter from Toowoomba Wellcamp Airport WTB. The most popular airlines in America Travel YouGov Ratings. Uses for sydney townsville flights sydney an extra charges clear field in. Regional carriers and sydney flights from individual service. Sydney to townsville Balsam. Book Sydney to Townsville Flight Tickets with Cleartrip. You may be neatly tucked away in darwin as the same destination. Get flight deals from Brisbane to Townsville Simply trim your desired city compare prices on flight routes and delay your holiday with. Very welcome to townsville from today for direct to do with one in the airline you right stopping in darwin on offer a booking has been professional and. How efficiently airlines flight distance from townsville flights on direct from the cheapest time around from sydney from sydney to compromise on. All flights sydney flight page section at sydney. Flight Centre managing director Graham Turner says vaccination programs will expand change. Still way to. Townsville Jetcost Cheap flights Dubbo. Sydney townsville sydney airport. -

Europcar Participating Locations AU4.Xlsx

Canberra Airport All Terminals, Terminal Building Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Canberra City Novotel City, 65 Northbourne Avenue Canberra ACT Alexandria 1053 Bourke Street Waterloo NSW Artarmon 1C Clarendon Street Artarmon NSW Blacktown 231 Prospect Highway Seven Hills NSW Coffs Harbour Airport Terminal Building Airport Drive Coffs Harbour NSW Coffs Harbour City 194 Pacific Highway Corner Bailey Avenue Coffs Harbour NSW Darling Harbour 320 Harris Street Pyrmont NSW Milperra 299-301 Milperra Road Milperra NSW Newcastle Airport Terminal Building, Williamtown Drive Williamtown NSW Newcastle City 20 Denison Street West NSW Parramatta 78-84 Parramatta Road Granville NSW Penrith 6-8 Doonmore Street Penrith NSW Sydney Airport All Terminals, Terminal Building, Sydney Airport Mascot NSW Sydney Central Inside Mercure Hotel, 818-820 George Street Sydney NSW Sydney City Pullman Hotel, 36 College Street Sydney NSW Wollongong 8A Flinders Street Wollongong NSW A&G Laverton 105 William Angliss Drive Laverton North VIC Albion 2/ 590 Ballarat Road Albion VIC Avalon 81 Beach Road Avalon VIC Bayswater 244 Canterbury Road Bayswater VIC Blackburn 110 Whitehorse Road Blackburn VIC Clayton 2093-2097 Princess Highway Clayton VIC Epping 18 Yale Drive Epping VIC Knox Woods Accident Repair Centre, 34 Gilbert Park Drive Knoxfield VIC Melbourne Airport All Terminals, Terminal Building, Melbourne Airport Tullamarine VIC Melbourne City 89-91 Franklin Street Melbourne VIC Moorabbin 245-247 Wickham Road Moorabbin VIC Preston 580 High Street Preston VIC Richmond 26 Swan -

QUEENSLAND SECTION 2016/17 the Furthest Corner

QUEENSLAND SECTION 2016/17 The furthest corner. The finest care. The furthest corner. The finest care. Providing excellence in primary health care and aeromedical service across Queensland. Contents Letters from the CEO and Chairman .................3 Year in numbers .....................................................6 Our people ..............................................................9 Queensland Fleet .................................................16 Service maps .........................................................18 Funding model ..................................................... 21 Our services ..........................................................23 Case study .............................................................34 Clinical Governance and Training .....................36 Queensland Section | 2016-2017 1 2 The furthest corner. The finest care. From the Chairman The past year has been one of considerable progress for RFDS Queensland Section, as we’ve pursued improvements designed to strengthen and future proof the organisation, while continuing to uphold our high standards of clinical and aviation performance and provide access to vital health care to over MARK GRAY – CHAIRMAN 90,000 people. In October 2016, with the assistance of industry experts This NSQHS accreditation is again an important in the health and aviation markets, Dr John O’Donnell independent and objective benchmark of the high (former CEO of Mater Health) and David Hall (former CEO standards of our patient care across our aeromedical of