2 Physical Characteristics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costa Rica 2020

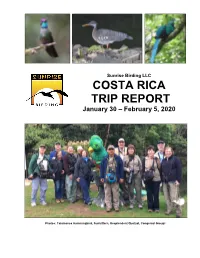

Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Photos: Talamanca Hummingbird, Sunbittern, Resplendent Quetzal, Congenial Group! Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Leaders: Frank Mantlik & Vernon Campos Report and photos by Frank Mantlik Highlights and top sightings of the trip as voted by participants Resplendent Quetzals, multi 20 species of hummingbirds Spectacled Owl 2 CR & 32 Regional Endemics Bare-shanked Screech Owl 4 species Owls seen in 70 Black-and-white Owl minutes Suzy the “owling” dog Russet-naped Wood-Rail Keel-billed Toucan Great Potoo Tayra!!! Long-tailed Silky-Flycatcher Black-faced Solitaire (& song) Rufous-browed Peppershrike Amazing flora, fauna, & trails American Pygmy Kingfisher Sunbittern Orange-billed Sparrow Wayne’s insect show-and-tell Volcano Hummingbird Spangle-cheeked Tanager Purple-crowned Fairy, bathing Rancho Naturalista Turquoise-browed Motmot Golden-hooded Tanager White-nosed Coati Vernon as guide and driver January 29 - Arrival San Jose All participants arrived a day early, staying at Hotel Bougainvillea. Those who arrived in daylight had time to explore the phenomenal gardens, despite a rain storm. Day 1 - January 30 Optional day-trip to Carara National Park Guides Vernon and Frank offered an optional day trip to Carara National Park before the tour officially began and all tour participants took advantage of this special opportunity. As such, we are including the sightings from this day trip in the overall tour report. We departed the Hotel at 05:40 for the drive to the National Park. En route we stopped along the road to view a beautiful Turquoise-browed Motmot. -

Sage-Grouse Hunting Season

CHAPTER 11 UPLAND GAME BIRD AND SMALL GAME HUNTING SEASONS Section 1. Authority. This regulation is promulgated by authority of Wyoming Statutes § 23-1-302 and § 23-2-105 (d). Section 2. Hunting Regulations. (a) Bag and Possession Limit. Only one (1) daily bag limit of each species of upland game birds and small game may be taken per day regardless of the number of hunt areas hunted in a single day. When hunting more than one (1) hunt area, a person’s daily and possession limits shall be equal to, but shall not exceed, the largest daily and possession limit prescribed for any one (1) of the specified hunt areas in which the hunting and possession occurs. (b) Evidence of sex and species shall remain naturally attached to the carcass of any upland game bird in the field and during transportation. For pheasant, this shall include the feathered head, feathered wing or foot. For all other upland game bird species, this shall include one fully feathered wing. (c) No person shall possess or use shot other than nontoxic shot for hunting game birds and small game with a shotgun on the Commission’s Table Mountain and Springer wildlife habitat management areas and on all national wildlife refuges open for hunting. (d) Required Clothing. Any person hunting pheasants within the boundaries of any Wyoming Game and Fish Commission Wildlife Habitat Management Area, or on Bureau of Reclamation Withdrawal lands bordering and including Glendo State Park, shall wear in a visible manner at least one (1) outer garment of fluorescent orange or fluorescent pink color which shall include a hat, shirt, jacket, coat, vest or sweater. -

Recent Literature

Vol.1940 XI RecentLiterature [63 RECENT LITERATURE Reviews by Margaret M. Nice and Thomas T. McCabe BANDING AND MIGRATION 1. Giiteborg's Natural History Museum's Ringing of Birds in 1938.-- (G6teborgs Naturhistoriska Museums Ringm•rkningar av Flyttf•g!er under 1938.) L. A. J•gerskiold1939. GOteborg'sMusei •rstryck, 1939; 91-108. In 1938 7,428 birds were ringed, making a total of 99,822 since 1911, with a retake figure of 3,482--3.5 per cent. Those ringed in greatest numbers were Black- headed and Common Gulls (Larus ridibundus and L. canus). Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris), and Common, Arctic and Sandwich Terns (Sterna hitundo, S. paradisea, and S. sandvicensis). 2. Results from Ringing Birds in Belgium.--(Oeuvre du Baguage des Oiseaux en Belgique.) Charles Dupond. 1939. Le Gerfaut, 29: 65-98. With the Brambling (Fringilla montifringilla) seven individuals returned to the same place in later winters, while others did not: six banded in October were found in Spain, France and Holland the same winter or the next; one was taken in Sweden the following winter 900 kilometers northeast of the place of banding; and one in Norway 1300 kilometers northeast. "Individual Migration" was found in the case of three species--Stock Dove (Columba oenas), Blackbird (Turdus rnerula) and Song Thrush (Turdus ericetoru,m),for some birds banded in the nest were sedentary while others migrated. 3. Fourth Banding Report of the Czecho-Slovakian Ornithological Society for the Year 1938. (IV. Beringungsbericht der TscheehischenOrni- thologischenGesellschaft for dasJahr 1938.) Otta Kadlec. 1939. Sylvia, 4: 33-55. Seventy-threeco6perators ringed 10,478 birds of 125 speciesin 1938. -

State-Owned Wildlife Management. Areas in New England

United States Department of State-Owned Agriculture I Forest Service Wildlife Management. Northeastern Forest Experiment Station Areas in New England Research Paper NE-623 Ronald J. Glass Abstract 1 State-owned wildlife management areas play an important role in enhancing 1 wildlife populations and providing opportunities for wildlife-related recreational activities. In the six New England States there are 271 wildlife management areas with a total area exceeding 268,000 acres. A variety of wildlife species benefit from habitat improvement activities on these areas. The Author RONALD J. GLASS is a research economist with the Northeastern Forest Experiment Station, Burlington, Vermont. He also has worked with the Economic Research Service of the US. Department of Agriculture and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. He received MS. and Ph.D. degrees in economics from the University of Minnesota and the State University of New York at Syracuse. Manuscript received for publication 13 February 1989 1 I Northeastern Forest Experiment Station 370 Reed Road, Broomall, PA 19008 I I July 1989 Introduction Further, human population growth and increased use of rural areas for residential, recreational, and commercial With massive changes in land use and ownership, the role development have resulted in additional losses of wildlife of public lands in providing wildlife habitat and related habitat and made much of the remaining habitat human-use opportunities is becoming more important. One unavailable to a large segment of the general public. Other form of public land ownership that has received only limited private lands that had been open to public use are being recognition is the state-owned wildlife management area posted against trespass, severely restricting public use. -

Gyrfalcon Diet in Central West Greenland During the Nesting Period

The Condor 105:528±537 q The Cooper Ornithological Society 2003 GYRFALCON DIET IN CENTRAL WEST GREENLAND DURING THE NESTING PERIOD TRAVIS L. BOOMS1,3 AND MARK R. FULLER2 1Boise State University Raptor Research Center, 1910 University Drive, Boise, ID 83725 2USGS Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center, 970 Lusk St., Boise, ID 83706 Abstract. We studied food habits of Gyrfalcons (Falco rusticolus) nesting in central west Greenland in 2000 and 2001 using three sources of data: time-lapse video (3 nests), prey remains (22 nests), and regurgitated pellets (19 nests). These sources provided different information describing the diet during the nesting period. Gyrfalcons relied heavily on Rock Ptarmigan (Lagopus mutus) and arctic hares (Lepus arcticus). Combined, these species con- tributed 79±91% of the total diet, depending on the data used. Passerines were the third most important group. Prey less common in the diet included waterfowl, arctic fox pups (Alopex lagopus), shorebirds, gulls, alcids, and falcons. All Rock Ptarmigan were adults, and all but one arctic hare were young of the year. Most passerines were ¯edglings. We observed two diet shifts, ®rst from a preponderance of ptarmigan to hares in mid-June, and second to passerines in late June. The video-monitored Gyrfalcons consumed 94±110 kg of food per nest during the nestling period, higher than previously estimated. Using a combi- nation of video, prey remains, and pellets was important to accurately document Gyrfalcon diet, and we strongly recommend using time-lapse video in future diet studies to identify biases in prey remains and pellet data. Key words: camera, diet, Falco rusticolus, food habits, Greenland, Gyrfalcon, time-lapse video. -

Ruffed Grouse Habitat Use in Western North Carolina

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2002 Ruffed Grouse Habitat Use in Western North Carolina Carrie L. Schumacher University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Schumacher, Carrie L., "Ruffed Grouse Habitat Use in Western North Carolina. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2002. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2192 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Carrie L. Schumacher entitled "Ruffed Grouse Habitat Use in Western North Carolina." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Wildlife and Fisheries Science. Craig A. Harper, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: David A. Buehler, Arnold Saxton Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Carrie L. Schumacher entitled “Ruffed Grouse Habitat Use in Western North Carolina.” I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Wildlife and Fisheries Science. -

The Birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an Annotated Checklist

European Journal of Taxonomy 306: 1–69 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2017.306 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2017 · Gedeon K. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A32EAE51-9051-458A-81DD-8EA921901CDC The birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an annotated checklist Kai GEDEON 1,*, Chemere ZEWDIE 2 & Till TÖPFER 3 1 Saxon Ornithologists’ Society, P.O. Box 1129, 09331 Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Germany. 2 Oromia Forest and Wildlife Enterprise, P.O. Box 1075, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. 3 Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, Centre for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F46B3F50-41E2-4629-9951-778F69A5BBA2 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F59FEDB3-627A-4D52-A6CB-4F26846C0FC5 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A87BE9B4-8FC6-4E11-8DB4-BDBB3CFBBEAA Abstract. Oromia is the largest National Regional State of Ethiopia. Here we present the first comprehensive checklist of its birds. A total of 804 bird species has been recorded, 601 of them confirmed (443) or assumed (158) to be breeding birds. At least 561 are all-year residents (and 31 more potentially so), at least 73 are Afrotropical migrants and visitors (and 44 more potentially so), and 184 are Palaearctic migrants and visitors (and eight more potentially so). Three species are endemic to Oromia, 18 to Ethiopia and 43 to the Horn of Africa. 170 Oromia bird species are biome restricted: 57 to the Afrotropical Highlands biome, 95 to the Somali-Masai biome, and 18 to the Sudan-Guinea Savanna biome. -

Nesting Behavior of Female White-Tailed Ptarmigan in Colorado

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 215 Condor, 81:215-217 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1070 NESTING BEHAVIOR OF FEMALE settling on the clutches. By lifting the hens off their WHITE-TAILED PTARMIGAN nests, we learned that eggs were laid almost immedi- ately after settling. IN COLORADO After eggs were laid, the hens remained relatively inactive until they prepared to depart from the nest. Observations of six hens in 1975 indicated that they KENNETH M. GIESEN remained on the nest for longer periods as the clutch AND approached completion. One hen depositing her sec- ond egg remained on her nest for 44 min, whereas CLAIT E. BRAUN another, depositing the fifth egg of a six-egg clutch, remained on the nest more than 280 min. Three hens remained on their nests 84 to 153 min when laying Few detailed observations on behavior of nesting their second or third eggs. Spruce Grouse also show grouse have been reported. Notable exceptions are this pattern of nest attentiveness (McCourt et al. those of SchladweiIer (1968) and Maxson (1977) 1973). who studied feeding behavior and activity patterns of Before departing from the nest, the hen began to Ruffed Grouse (Bonasa umbellus) in Minnesota, and peck at vegetation and place it at the rim of the McCourt et al. ( 1973) who documented nest atten- nest, or throw it over her back. This behavior lasted tiveness of Spruce Grouse (Canachites canudensis) in 34, 40 and 64 min for three hens. Vegetation was southwestern Alberta. White-tailed Ptarmigan (Lugo- deposited on the nest at the rate of 20 pieces per pus Zeucurus) have been intensively studied in Colo- minute. -

Wild Turkey Education Guide

Table of Contents Section 1: Eastern Wild Turkey Ecology 1. Eastern Wild Turkey Quick Facts………………………………………………...pg 2 2. Eastern Wild Turkey Fact Sheet………………………………………………….pg 4 3. Wild Turkey Lifecycle……………………………………………………………..pg 8 4. Eastern Wild Turkey Adaptations ………………………………………………pg 9 Section 2: Eastern Wild Turkey Management 1. Wild Turkey Management Timeline…………………….……………………….pg 18 2. History of Wild Turkey Management …………………...…..…………………..pg 19 3. Modern Wild Turkey Management in Maryland………...……………………..pg 22 4. Managing Wild Turkeys Today ……………………………………………….....pg 25 Section 3: Activity Lesson Plans 1. Activity: Growing Up WILD: Tasty Turkeys (Grades K-2)……………..….…..pg 33 2. Activity: Calling All Turkeys (Grades K-5)………………………………..…….pg 37 3. Activity: Fit for a Turkey (Grades 3-5)…………………………………………...pg 40 4. Activity: Project WILD adaptation: Too Many Turkeys (Grades K-5)…..…….pg 43 5. Activity: Project WILD: Quick, Frozen Critters (Grades 5-8).……………….…pg 47 6. Activity: Project WILD: Turkey Trouble (Grades 9-12………………….……....pg 51 7. Activity: Project WILD: Let’s Talk Turkey (Grades 9-12)..……………..………pg 58 Section 4: Additional Activities: 1. Wild Turkey Ecology Word Find………………………………………….…….pg 66 2. Wild Turkey Management Word Find………………………………………….pg 68 3. Turkey Coloring Sheet ..………………………………………………………….pg 70 4. Turkey Coloring Sheet ..………………………………………………………….pg 71 5. Turkey Color-by-Letter……………………………………..…………………….pg 72 6. Five Little Turkeys Song Sheet……. ………………………………………….…pg 73 7. Thankful Turkey…………………..…………………………………………….....pg 74 8. Graph-a-Turkey………………………………….…………………………….…..pg 75 9. Turkey Trouble Maze…………………………………………………………..….pg 76 10. What Animals Made These Tracks………………………………………….……pg 78 11. Drinking Straw Turkey Call Craft……………………………………….….……pg 80 Section 5: Wild Turkey PowerPoint Slide Notes The facilities and services of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources are available to all without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, age, national origin or physical or mental disability. -

Than a Meal: the Turkey in History, Myth

More Than a Meal Abigail at United Poultry Concerns’ Thanksgiving Party Saturday, November 22, 1997. Photo: Barbara Davidson, The Washington Times, 11/27/97 More Than a Meal The Turkey in History, Myth, Ritual, and Reality Karen Davis, Ph.D. Lantern Books New York A Division of Booklight Inc. Lantern Books One Union Square West, Suite 201 New York, NY 10003 Copyright © Karen Davis, Ph.D. 2001 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of Lantern Books. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data For Boris, who “almost got to be The real turkey inside of me.” From Boris, by Terry Kleeman and Marie Gleason Anne Shirley, 16-year-old star of “Anne of Green Gables” (RKO-Radio) on Thanksgiving Day, 1934 Photo: Underwood & Underwood, © 1988 Underwood Photo Archives, Ltd., San Francisco Table of Contents 1 Acknowledgments . .9 Introduction: Milton, Doris, and Some “Turkeys” in Recent American History . .11 1. A History of Image Problems: The Turkey as a Mock Figure of Speech and Symbol of Failure . .17 2. The Turkey By Many Other Names: Confusing Nomenclature and Species Identification Surrounding the Native American Bird . .25 3. A True Original Native of America . .33 4. Our Token of Festive Joy . .51 5. Why Do We Hate This Celebrated Bird? . .73 6. Rituals of Spectacular Humiliation: An Attempt to Make a Pathetic Situation Seem Funny . .99 7 8 More Than a Meal 7. -

Hunting Regulations

WYOMING GAME AND FISH COMMISSION Upland Game Bird, Small Game, Migratory 2021 Game Bird and Wild Turkey Hunting Regulations Conservation Stamp Price Increase Effective July 1, 2021, the price for a 12-month conservation stamp is $21.50. A conservation stamp purchased on or before June 30, 2021 will be valid for 12 months from the date of purchase as indicated on the stamp. (See page 5) wgfd.wyo.gov Wyoming Hunting Regulations | 1 CONTENTS GENERAL 2021 License/Permit/Stamp Fees Access Yes Program ................................................................... 4 Carcass Coupons Dating and Display.................................... 4, 29 Pheasant Special Management Permit ............................................$15.50 Terms and Definitions .................................................................5 Resident Daily Game Bird/Small Game ............................................. $9.00 Department Contact Information ................................................ 3 Nonresident Daily Game Bird/Small Game .......................................$22.00 Important Hunting Information ................................................... 4 Resident 12 Month Game Bird/Small Game ...................................... $27.00 License/Permit/Stamp Fees ........................................................ 2 Nonresident 12 Month Game Bird/Small Game ..................................$74.00 Stop Poaching Program .............................................................. 2 Nonresident 12 Month Youth Game Bird/Small Game Wild Turkey -

Birdobserver12.6 Page358 Index, Volume 12, 1984.Pdf

INDEX, VOLUME 12, 1984 VOLUME 12: N o . 1: pp. 1-60 N o . 2: pp. .-124. No. 3: pp. 125 -176 N o. 4; pp. 177-244 N o . 5: pp. [5-300 No. 6: pp. 301 -360 At A Glance; Black Scoter Female Wayne R. Petersen 59, 122 Brambling H. Christian Floyd 243, 297 Clay-colored Sparrow Pat Fox and Mary Baird 58 Heath Hen Dorothy R. Arvidson 123, 172 Kentucky Warbler George W. Gove 175, 242 Swamp Sparrow Richard Walton 299, 356 Birding at a Solar Eclipse Leif J. Robinson 277 Book Reviews; Erma J. Fisk: The Peacocks of Baboquivari Patricia N. Fox 91 National Geographic Society's The Wonder of Birds Michael R. Greenwald 26 Bridled Tern Sighting off Gloucester, Massachusetts Walter G. Ellison 351 A Decade of Wintering Brant in Boston Harbor Leif J. Robinson 52 The Decline and Fall of Tympanuchus cupido cupido Dorothy R. Arvidson 172 E. B. White, Forbush, and the Birds of Massachusetts Barbara Phillips and Dorothy R. Arvidson 145 The Field Identification of Arctic Loon Terence A. Walsh 309 Field Notes from Here and There; Arctic Encounter at Plum Island David Lange 117 Clever Jackdaw Robert Abrams 119 Foolish Pelican Robert H. Stymeist 119 High Arctic Spectacle Dorothy S . Long 117 A Leucistic Black-bellied Plover George W. Gove 355 News About Jackdaws Martha Vaughan 355 Starling Fracas Lee E. Taylor 118 Field Records: George W. Gove, October 1983 29 April 1984 215 Robert H. Stymeist, November 1983 41 May 1984 226 and Lee E. Taylor December 1983 95 June 1984 280 January 1984 107 July 1984 289 February 1984 155 August 1984 328 March 1984 162 September 1984 337 A Fuddle of Falcons Nancy Clayton 267 Further Notes on the Field Identification of Winter- plumaged Arctic Loons Terence A.