Heritage Building Conservation Technical Advice Sheet 5 Dealing with Dampness in Old Walls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Damp-Proofer & Waterproofer

Damp-Proofer & Waterproofer AQUAPRUFE Date: 03 October 2016 Fact Sheet No.: TDS00461 YOUR SMART ADVANTAGES and out of direct sunlight. Protect from frost. For concrete and brick walls & floors TYPICAL PERFORMANCE DATA (Approx.) Can be applied to damp surfaces Application +5°C to +35°C Temperature Brush on Viscosity 4000-9000 MPas USES Drying Time Approx. 24 hours per coat depending Bostik Aquaprufe Damp-Proofer & Waterproofer is a on drying conditions. However flexible, cold applied, odourless, rubber enriched bitumen product always remains tacky emulsion for use both internally and externally. Coverage Floors: 1.25m2 per litre per coat Bostik Aquaprufe Damp-Proofer & Waterproofer provides a highly efficient sandwich damp-proof membrane for floors Walls: 2m2 per litre per coat - Bostik Aquaprufe Damp-Proofer & Waterproofer must be overlaid with a minimum 50mm flooring screed. It also acts Depending on application technique as a waterproofer for walls when plastered or plaster and ambient conditions boarded over. Bostik Aquaprufe Damp-Proofer & Waterproofer must always be covered as it remains tacky. Solvent for Cleaning Warm soapy water whilst still wet Up White spirit when dry PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS Colour Dark Brown, dries black DIRECTIONS FOR USE IMPORTANT: Before using Bostik Aquaprufe Damp-Proofer Form A structured liquid & Waterproofer refer to the relevant Health & Safety Data Sheet, available at www.bostik.co.uk. Specific Gravity 1.0 approx. PREPARATION Composition Bitumen and rubber latex aqueous 1. Bostik Aquaprufe Damp-Proofer & Waterproofer dispersion should be applied to slightly damp, not wet surfaces. Do not apply outdoors when raining or if there is risk of Product Codes 30812206 2.5 Litre x 6 rain, frost, fog, or dew before Bostik Aquaprufe Damp- 30812207 5 Litre x 4 Proofer & Waterproofer has dried. -

Omnimat Flexible, Damp-Resistant And

WD OMNIMAT DECOUPLING MEMBRANE FLEXIBLE, DAMP-RESISTANT AND WATERPROOF MAT, WITH ACCESSORIES FOR LAYING UNDER TILES Characteristic product properties n Very good chemical resistance. n Suitable for surfaces that are sensitive to moisture, such as wood, plasterboard and plaster coatings. n Only a very thin 0.4 mm layer is required. n Can be used on walls and floors. n Suitable for interior and exterior use under certain conditions. Applications Using WD omnimat and these accessories ensures a perfect damp-proof seal and decoupling under tiles and natural stone. The mat has very good chemical resistance and can easily be used on surfaces that are sensitive to moisture, such as wood, plasterboard and plaster coatings. Showers, bathrooms, sports facilities, spa facilities and areas affected by intense moisture are just a few examples of how it can be used. If you would like to use it in swimming pools and other specific applications, we recommend that you contact us. Appropriate surfaces n Anhydrite (white powder adhesive) n Approved fibre-plaster boards n Brick (white powder adhesive) n Existing tiles n Pressed wood fibres/underlayment n Concrete n Multiplex wood n Concrete blocks n Lime-cement coating n Cellular concrete n Sand-limestone n Cement coating n Ceramic interior bricks n Cement screed n Cork n Cement screed with underfloor heating n O-BOARD n Electric underfloor heating n Polystyrene board n Epoxy coating n Decorative coating n Plaster coating (white powder adhesive) n Silicate board n Plaster blocks (white powder adhesive) n Stone carpet n Plasterboard n Paint n Approved fibre-cement boards n Wall heating For specific details, please refer to our “General instructions for surfaces”. -

Thermal and Moisture Protection: Keeping the Weather out Internet Course

Rich Text Editor,editor1 http://www.licensetobuild.com/web-class/controls/?mt=coursemanagem... Thermal and Moisture Protection: Keeping the Weather Out Internet Course Learning Objectives Summarize the key elements (either natural or mechanical) of a properly ventilated structure. List and describe at least three specific installation techniques and/or materials that contribute to a properly constructed roof system. Outline at least one design strategy based on "best practices" for the construction of buildings in areas with high humidity. Identify and implement proven methods that will effectively divert moisture from the foundation of a structure. Keeping the Weather Out Protecting buildings from weather and moisture related problems is important for all building professionals. In areas of high humidity, (and ALL Florida counties are considered "warm humid counties" by the Florida Building Code: Energy Conservation 301.2), it is even more important that builders, their employees, and their subcontractors use “Best Practice” procedures to carefully install thermal and weather resistant components. Because of the potential for loss due to consumer complaints and claims, it makes sense for contractors to be trained in moisture control for the homes and buildings they are constructing or renovating. Major performance objectives. One objective of a building envelope system is to provide moisture control. Construction of a building envelope system needs to incorporate methods and materials that prevent or minimize the impact of moisture intrusion. The photo below shows typical damage caused by poorly installed or maintained building envelope components! Too often, exterior shells are simply sealed up without regard for proper installation of house- wraps, flashing and ventilation. -

Lime Plaster & Plaster Lath for Damp Buildings

Lime Plaster & Plaster Lath for Damp Buildings Lime Plaster & Plaster Lath for Damp Buildings Surveying for Damp Issues with Historic Buildings. Buildings fall into two categories for the purposes of surveying for damp: I. Modern buildings built with a damp proof course and barriers to rainwater penetration. II. Old buildings built prior to mid to late 19th century depending upon the region of the country. Old buildings relied on the walls breathing and shedding moisture before damp became a problem. Damp Proofing Old Buildings In old buildings, walls were built to such a thickness that normally damp would not penetrate to the inside. The joints were always of lime mortar or earth and were more porous than the building’s structural elements comprising brick, stone etc. Consequently the joints would drain and shed water by evaporation, therefore not allowing damage to these structural elements. The joints were the sacrificial element of the building. Because lime and earth mortars are so porous, timber in contact with these mortars is less prone to decay than when bedded in cement mortar. Historic houses, when built, were able to breathe and shed water. They were also heated by coal or log fires in an open fireplace which promoted rapid air changes by way of air being drawn out through the chimney. Windows and doors were not sealed as they are today allowing air movement into and out of the building. Internal finishes were lime washed which allowed surfaces to breathe and, although it would discolour when damp, it would not peal off the wall like wall paper nor blister like modern paint. -

Model Building Bye Laws Brought out in 2004

,2016 Revised and Published in 2016. © Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India, 2016 Material from this publication may be used for educational or other purposes with due credits. Overall guidance Sh. Neeraj Mandloi, IAS. Joint Secretary, Ministry of Urban Development, Govt. of India Technical Team TCPO Late Sh. J.B. Kshirsagar. Former Chief Planner Sh. R. Srinivas TCP (Head), MUT Division Sh. Sudeep Roy Assistant TCP Ms. D Blessy Assistant TCP Stakeholders in Consultative Workshop Central Governments agencies/ Institutes: National Disaster Management Authority Bureau of Indian Standards National Building Construction Corporation National Remote Sensing Centre Delhi Development Authority National Capital Region Planning Board Indian Institute of Public Administration Municipal Corporation of Delhi (South) Housing and Urban Development Corporation Schools of Planning and Architecture State Government Departments State Town and Country Planning Departments Selected Urban Development Authorities Selected Urban Local Bodies. Associations like CREDAI and NAREDCO Expert Review Prof. Dr. PSN Rao Chairman, Delhi Urban Arts Commission. New Delhi PRELUDE Building Bye-Laws are legal tools used to regulate coverage, height, building bulk, and architectural design and construction aspects of buildings so as to achieve orderly development of an area. They are mandatory in nature and serve to protect buildings against fire, earthquake, noise, structural failures and other hazards. In India, there are still many small and medium sized towns which do not have building bye-laws and in the absence of any regulatory mechanism, such towns are confronted with excessive coverage, encroachment and haphazard development resulting in chaotic conditions, inconvenience for the users, and disregard for building aesthetics, etc. -

10 Year Solution – Exterior Walls

Summary - 10 year solution – exterior walls Remove plaster up to 1.2m above DPC line Re-glue brittle bricks with Dampsure GlueBack Drill 12mm dia holes one brick above highest ground level, min 100mm apart Inject chemical DPC Cream stopping future rising damp Waterproof wall where plaster was removed with Dampsure Dampcrete47 – prevent retained moisture to permeate into new plaster Apply mixture of Bonding Liquid with river sand to waterproofed wall Re-plaster with Dampsure Plastersure Plaster Additive – capillaries in plaster are rubberised and Salt Neutraliser prevents forming of efflorescence (bubbling of paint) Put a Dampcrete47 waterproofing sock onto new plaster Paint 28 days after remedial work was done The diagram below depicts the process to be followed: Dampsure is achieving phenomenal damp proofing results with its 10 year rising damp solution. This recipe has been designed in Europe to fix rising damp problems. This recipe is long lasting and has stood the test of time. Dampsure has had no comebacks or failures on the above recipe. Dampsure Cnr Hendrik Potgieter & Gordon rd, Florida 083 501 0060 Recipe - Rising damp – 10 year solution Preparation Warning!! before You are going to work with moisture and products that may damage floors and furniture. starting with Cover all tile floors, paving etc with plastic to minimize moisture and or chemical damage project and or water ingress Tape aluminium window and door frames with yellow aluminium tape Cover window panes with plastic Tape all pipes and fittings on walls Close all electrical points with waterproofing tape or plastic Remove all skirting and fixtures that are in the area that will be treated Identify the areas where water pipes and electrical wires might be damaged by drilling or chipping, mark these area and handle these areas with care. -

Practical Building Conservation

ENGLISH HERITAGE PRACTICAL BUILDING CONSERVATION BUILDING ENVIRONMENT ENVIRO27JULY2014.inddENVIRO 27 JULY 2014.indd a 29/07/2014 00:00 © English Heritage 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. English Heritage has asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author and editor of this work. English Heritage 1 Waterhouse Square 138–142 Holborn London EC1N 2ST Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East Suite 420 Union Road 101 Cherry Street Farnham Burlington Surrey GU9 7PT VT 05401-4405 England USA www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Practical building conservation. Building environment. 1. Building materials–Environmental aspects. 2. Weathering of buildings. 3. Historic buildings– Conservation and restoration. I. English Heritage. 720‘.288-dc22 Library of Congress Control Number: 2001012345 ISBN-13: 9780754645580 ENVIRO 27 JULY 2014.indd b 06/08/2014 09:51 To the memory of John Ashurst (1937–2008), an inspiration and friend to all the editors, whose encouragement and support was a great motivation for this new series of Practical Building Conservation. ENVIRO 27 JULY 2014.indd c 29/07/2014 00:16 ENGLISH HERITAGE PRACTICAL BUILDING CONSERVATION BUILDING ENVIRONMENT Series Editors: Bill Martin and Chris Wood Volume Editors: Robyn Pender, Brian Ridout, Tobit Curteis ENVIRO 27 JULY 2014.indd i 29/07/2014 00:20 ii NOTES ON VOLUME EDITORS & CONTRIBUTORS Volume Editors & Principal Authors: Robyn Pender, Brian Ridout, Tobit Curteis Dr Robyn Pender is a Senior Architectural Conservator in the Building Conservation and Research Team at English Heritage, and serves on the Cathedrals Fabric Commission for England. -

Damp Proofing Footing , Columns

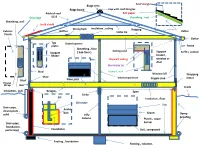

Roof shingles Ridge vent Ridge Board Cap with roof shingles. Pitch of roof Felt paper Drip edge 5/12 Sheathing , roof Sheathing, wall Ice & shield Strong back Insulation , ceiling Bridging Exterior Baffles Collar tie Rafter Finish Gutter Top Underlayment plates Fascia Sheathing , floor Ceiling Joist Support ( Sub-floor ) Support Soffit / vented Header header , Drywall, ceiling window or door Hurricane tie Stud Drywall , wall Window Sill Strapping Shoe Interior partition Cripple stud metal Stud Floor joist House Wrap Box Grade Insulation , wall Bridging Span Girder Sill Insulation , floor Sill sealer Slab Drain pipe, Anchor downspouts , bolt Gravel solid Lally Damp proofing Column Plastic , vapor Drain pipe, barrier foundation , perforated Foundation Soil , compacted Footing , foundation Footing , columns MaterialMaterial Description Function Alphabetical order AnchorAnchor Bolt Bolt Galvanized J- shape bolt, 1/2” dia. ( 8” – 16” long ) , treaded on top with galvanized washer & nut. Secures wooden sill to concrete foundation. BafflesBafflesBaffles Plastic or Styrofoam , pre made to fit between rafters , slightly contoured to create a cavity Creates a barrier ( Air-Flow ) between roof & insulation BridgingBridging Wood installed perpendicular to either floor or ceiling joist at mid span. Unites joist thus distributes the weight , prevents joist from twisting BoxBox Outer perimeter floor member , single when perpendicular to floor joist , double when parallel. Structural member , supports weight of exterior walls . CeilingCeiling Joist joist Wood structurally member , varies in size based on span , usually installed 16” on center. Prevents exterior walls from bowing out , nailing surface for drywall CollarCollar Tie tie Wood framing ( usually 2” x 4” or 2” x 6 “ or 1” x 6” ) , secured to opposing rafters. -

Moisture Control Guidance for Building Design

www.epa.gov/iaq/moisture Foundations Issue control the surface flow of water, or meet a more stringent local building code requirement. Applying Building foundations are vulnerable to moisture this slope to a distance of 6 to 10 feet from the problems for a number of reasons, including: foundation generally is acceptable. • Reduce water infiltration into the soil surrounding • Water from rain and from plumbing leaks is drawn the building using a barrier at or slightly beneath by gravity to foundations, which are exposed to the surface (e.g., a cap of silty-clay soil or surface water, rain-soaked soil and, possibly, high subsurface drainage landscape membrane). Care water tables. must be taken to prevent the roots of plants in this • Water may condense on foundation materials during zone from penetrating the barrier. warm weather because the materials are cooler than • Design the foundation and surrounding grade the outdoor air. so there is a minimum of 8 inches of exposed • Crawl spaces and basements are holes in the foundation after the final grading. ground and have more extensive contact with soil than slab-on-grade foundations. Guidance 2: Design below-grade drainage systems to divert water away from the foundation and specify • Many moisture problems can be avoided by properly capillary breaks to keep water from wicking through designing the foundation. Moisture problems the foundation to moisture-sensitive materials (e.g., associated with improperly designed foundations wooden framing and paper-covered gypsum board). can be difficult and expensive to identify and fix, can create the potential for health problems resulting from mold growth, and can be a liability Slab-On-Grade Liquid Water Control (See Figure 2-2) for building owners. -

Damp Proofing Or a Damp Proof in Construction Is a Type of a Moisture

DAMP PROOFING Damp proofing or a damp proof in construction is a type of a moisture control applied to building walls and floors to prevent moisture from passing into the interior spaces. Dampness problems are among the most frequent problem encountered in residences. MATERIAL USED FOR DAMP PROOFING 1. Property of the material An effective damp proofing material should have the following properties 1. It should be impervious. 2. It should be strong and durable and should be capable of withstanding both dead as well as live loads without damage. 3. It should be dimensionally stable 4. It should be free from deliquescent salts like sulphates chlorides and nitrates 5. The material should be reasonably cheap. 6. The material should be such that it is possible to carry out leak proof joining work. 2. Classification of material The materials commonly used to check dampness can be divided into the following four categories a) Flexible material Material like bitumen felts (which may be Hessian based or fibre/glass fibre based), plastic sheeting (polythene sheet) etc b) Semi rigid materials Materials like mastic asphalts or combination of materials or layers. c) Rigid materials Materials like first class bricks, stones, slates, cement concrete etc d) Grout materials Grout consists of cement slurry and acrylic based chemical or polymers. 3. Material used for damp proofing Following are the materials, which are commonly used for damp proofing. 1. Hot bitumen This is a flexible material and is placed on the bedding of concrete or mortar. This material should be applied with a minimum thickness of 3 mm. -

Damp Proofing Material

Damp Proofing Material 1- Flexible Materials: The materials, which do not crack and deform their shape when subjected to loading, are called Flexible Materials a- Bitumen Mastic (Mastic Asphalt) It consists of asphalt or bitumen mixed with fine sand in hot state to form an impervious mass. Due to this consistency it can be spread (when hot) to a depth of 2.5cm to 5cm, which sets on cooling. It provides good impervious layer but special care is needed in its laying. b- Bitumen Felts (Sheets): It consists of 6mm thick sheet of bitumen prepared in rolls having width equal to that of brick wall. c- Hot laid Bitumen: This material is used on a bedding of cement concrete or mortar. This should be applied in two layers at the rate of 1.75kg/ m2 of the area. d- Metal Sheets: Metal sheets of Copper, Aluminum, or Lead are used to prevent dampness, but they are costly. Sheets of these materials are used through out the thickness of the wall. The sheets of Lead are laid over Lime Mortar and not with Cement Mortar due to the chemical reaction of Cement over the Lead. The sheets of metal should be coated with asphalt. The thickness of the sheets should not be less than 3mm. 2- Rigid Materials: The materials, which do not resist transverse stresses and cracks when subjected to sever loading, are known as Rigid Materials. a- Rich Concrete 1.2cm to 4cm thick layer of Rich Concrete (1:2:4) painted with two coats of hot bitumen is used as horizontal D.P.C. -

Brochure Industry Object

Tiling for industrial, commercial & residential construction Specialist systems for the professional tiler Tiling systems for industrial, commercial & residential construction Specialist systems for professional tilers Expert Building Materials www.botament.com Tiling Wet Spaces Spas, Pools and Bathrooms • Public Showers 6 - 7 • Swimming Pools 8 - 9 • Spas (Wellness Facilities) 10 - 11 Industry • Industrial Kitchens 12 - 13 • Food & Drinks Industry 14 - 15 • Car Wash Plants 16 - 17 • Application Details - Wet Spaces 18 - 23 Tiling Requiring High Mechanical Strength • Factories and Warehouses 24 - 25 Electrically Conductive Tiling • Work Areas With Electrically Conductive Tiling 26 - 27 • Application Details Electrically Conductive Tiling 28 - 29 • Regulations 30 - 31 The information provided here as product description is based on our experience and is given to the best of our knowledge, but is non-binding. All instructions must be adapted to suit the individual building projects, the application purpose and the specific local conditions. To achieve optimal results we recommend carrying out a site-specific test application first. In any 2 case, the generally accepted technical rules must be adhered to. Tiling for industry and commerce. A job for professional tilers alone! Tile fitting in industrial kitchens, swimming Our effective and easy to understand product pro- pools, production halls and other specialist areas gramme, consisting of components that have been not only demand the highest level of professio- developed to build harmonised systems, offer our nal skill, fitters also have to have detailed expert customers the highest level of application security, to- know how of all applicable requirements and sta- gether with the highest degree of flexibility - all thanks tutory guidelines valid at the time of fitting.