Controversial Art in the Community College. PUB DATE 2003-00-00 NOTE 26P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6:00 Pm 11 Expo Center 12 Orlando, Florida 13 14 15 16 1

Page 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 REAPPORTIONMENT PUBLIC HEARING 8 9 10 AUGUST 20, 2001 - 6:00 P.M. 11 EXPO CENTER 12 ORLANDO, FLORIDA 13 14 15 16 17 18 REPORTED BY: 19 KRISTEN L. BENTLEY, COURT REPORTER 20 Division of Administrative Hearings 21 DeSoto Building 22 1230 Apalachee Parkway 23 Tallahassee, Florida 24 25 Page 2 Page 4 1 MEMBERS IN ATTENDANCE 1 REPRESENTATIVE ALLEN TROVILLION 2 SENATOR GINNY BROWN-WAITE 2 REPRESENTATIVE MARK WEISSMAN 3 SENATOR LEE CONSTANTINE 3 REPRESENTATIVE FREDERICA S. WILSON 4 SENATOR ANNA P. COWIN 4 REPRESENTATIVE ROGER B. WISHNER 5 SENATOR MANDY DAWSON 5 6 SENATOR BUDDY DYER 6 7 SENATOR BETTY S. HOLZENDORF 7 8 SENATOR JAMES E. KING, JR. 8 9 SENATOR RON KLEIN 9 10 SENATOR JACK LATVALA 10 11 SENATOR JOHN F. LAURENT 11 12 SENATOR DURELL PEADEN, JR. 12 13 SENATOR BILL POSEY 13 14 SENATOR RONALD A. SILVER 14 15 SENATOR J. ALEX VILLALOBOS 15 16 SENATOR DEBBIE WASSERMAN-SCHULTZ 16 17 SENATOR DANIEL WEBSTER 17 18 REPRESENTATIVE BOB ALLEN 18 19 REPRESENTATIVE CAREY BAKER 19 20 REPRESENTATIVE GUS MICHAEL BILIRAKIS 20 21 REPRESENTATIVE RANDY BALL 21 22 REPRESENTATIVE MARSHA L. BOWEN 22 23 REPRESENTATIVE FREDERICK C. BRUMMER 23 24 REPRESENTATIVE JOHNNIE B. BYRD, JR. 24 25 REPRESENTATIVE FRANK ATTKISSON 25 Page 3 Page 5 1 REPRESENTATIVE LARRY CROW 1 PROCEEDINGS 2 REPRESENTATIVE JOYCE CUSACK 2 CHAIRMAN BYRD: The Joint Legislative Committee 3 REPRESENTATIVE DON DAVIS 3 meeting will now come to order. Thank you, ladies and 4 REPRESENTATIVE MARIO DIAZ-BALART 4 gentlemen, for coming to this meeting. -

The Journal of the House of Representatives

The Journal OF THE House of Representatives ORGANIZATION SESSION Tuesday, November 21, 2000 Journal of the House of Representatives for the Organization Session of the 80th House since Statehood in 1845, convened under the Constitution, begun and held at the Capitol in the City of Tallahassee in the State of Florida on Tuesday, November 21, 2000, being the day fixed by the Constitution for the purpose. John B. Phelps, the Clerk of the preceding session, delegated the 28—Suzanne M. Kosmas, New Smyrna Beach duties of temporary presiding officer to the Honorable John Thrasher, 29—Randy Ball, Mims retiring Speaker. Mr. Thrasher called the House to order at 10:00 a.m. 30—Mike Haridopolos, Melbourne 31—Mitch Needelman, Melbourne The following certified list of Members elected to the House of 32—Bob Allen, Rockledge Representatives was received: 33—Tom Feeney, Oviedo 34—David J. Mealor, Lake Mary State of Florida 35—Jim Kallinger, Winter Park 36—Allen Trovillion, Winter Park Office of Secretary of State 37—David Simmons, Longwood I, Katherine Harris, Secretary of State of the State of Florida, do 38—Frederick C. Brummer, Apopka hereby certify that the following Members of the House of 39—Gary Siplin, Orlando Representatives were elected at the General Election held on the 40—Andy Gardiner, Orlando Seventh day of November, A.D., 2000, as shown by the election returns 41—Randy Johnson, Celebration on file in this office: 42—Hugh Gibson, Lady Lake 43—Nancy Argenziano, Dunnellon HOUSE DISTRICT ELECTED MEMBERS 44—Dave Russell, Brooksville NUMBER 45—Mike Fasano, New Port Richey 1—Jeff Miller, Pace 46—Heather Fiorentino, New Port Richey 2—Jerry L. -

Panama City Transcript.Ptx

Page 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 REAPPORTIONMENT PUBLIC HEARING 8 9 10 OCTOBER 16, 2001 - 11:00 A.M. 11 FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY 12 PANAMA CITY, FLORIDA 13 14 15 16 17 18 REPORTED BY: 19 MONA L. WHIDDON 20 COURT REPORTER 21 Division of Administrative Hearings 22 DeSoto Building 23 1230 Apalachee Parkway 24 Tallahassee, Florida 25 DIVISION OF ADMINISTRATIVE HEARINGS (850) 488-9675 Page 2 Page 4 1 MEMBERS IN ATTENDANCE 1 constituents. We must not diminish their voice by taking 2 SENATOR CHARLIE CLARY 2 up valuable time today in debate. 3 SENATOR DARYL L. JONES 3 Following my brief remarks counsel will give a general 4 SENATOR JACK LATVALA 4 overview of legal considerations of redistricting. Staff 5 SENATOR ALFRED LAWSON, JR. 5 will then provide some specific information about census 6 SENATOR DURELL PEADEN, JR. 6 results in this region and the state. The rest is reserved 7 SENATOR DANIEL WEBSTER 7 for you, the citizens. 8 REPRESENTATIVE RANDY BALL 8 Every ten years after the completion of the national 9 REPRESENTATIVE MARIO DIAZ-BALART 9 census the Constitution requires that the Florida 10 REPRESENTATIVE DENNIS BAXLEY 10 Legislature redraw boundaries for all districts of the 11 REPRESENTATIVE ALLEN BENSE 11 Florida House, the Florida Senate, and the United States 12 REPRESENTATIVE DON BROWN 12 Congress. 13 REPRESENTATIVE EDWARD L. JENNINGS, JR. 13 The Legislature will take up this task in the 14 REPRESENTATIVE BEV KILMER 14 legislative session that begins January 22nd, 2002, and 15 REPRESENTATIVE DICK KRAVITZ 15 ends March 22nd, 2002. -

7-12 Hearing Transcript.EXE

Page 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 REAPPORTIONMENT PUBLIC HEARING 8 9 10 JULY 12, 2001 11 10:00 a.m. - 1:15 p.m. 12 ROOM 212, KNOTT BUILDING 13 TALLAHASSEE, FLORIDA 14 15 16 17 18 19 REPORTED BY: 20 KRISTEN L. BENTLEY, COURT REPORTER 21 22 23 24 25 Page 2 Page 4 1 MEMBERS IN ATTENDANCE 2 SENATOR DANIEL WEBSTER 1 PROCEEDINGS SENATOR JOHN F. LAURENT, JR. 2 SENATOR WEBSTER: Good morning, members and 3 SENATOR GINNY BROWN-WAITE SENATOR LISA CARLTON 3 legislature. My name is Daniel Webster. I'm a Senator 4 SENATOR CHARLIE CLARY SENATOR LEE CONSTANTINE 4 from District 12 and chairman of the Senate Redistricting 5 SENATOR ANNA P. COWIN SENATOR MANDY DAWSON 5 Committee. It's my pleasure to welcome you today to this 6 SENATOR BUDDY DYER SENATOR BETTY HOLZENDORF 6 public hearing. 7 SENATOR DARYL JONES SENATOR RON KLEIN 7 Representatives and senators are here to listen to the 8 SENATOR AL LAWSON, JR. SENATOR LES MILLER, JR. 8 residents of this area and consider your input in this very 9 SENATOR RICHARD MITCHELL SENATOR DEBBY SANDERSON 9 important process. Since these joint meetings -- since 10 SENATOR BURT L. SAUNDERS SENATOR JIM SEBESTA 10 these are joint meetings, we divided up our 11 SENATOR ROD SMITH SENATOR DONALD SULLIVAN, M.D. 11 responsibilities throughout the many public hearings, 20 to 12 SENATOR J. ALEX VILLALOBOS SENATOR DEBBIE WASSERMAN-SCHULTZ 12 be exact, that will take place throughout the state in the 13 REPRESENTATIVE RANDY BALL REPRESENTATIVE JOHNNIE BYRD 13 next few weeks. -

STATISTICS of the PRESIDENTIAL and CONGRESSIONAL ELECTION of NOVEMBER 2, 2004 (Number Which Precedes Name of Candidate Designates Congressional District

STATISTICS OF THE PRESIDENTIAL AND CONGRESSIONAL ELECTION OF NOVEMBER 2, 2004 SHOWING THE HIGHEST VOTE FOR PRESIDENTIAL ELECTORS, AND THE VOTE CAST FOR EACH NOMINEE FOR UNITED STATES SENATOR, REPRESENTATIVE, RESIDENT COMMIS- SIONER, AND DELEGATE TO THE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS, TOGETHER WITH A RECAPITULATION THEREOF, INCLUDING THE ELECTORAL VOTE COMPILED FROM OFFICIAL SOURCES BY JEFF TRANDAHL CLERK OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES (Corrected to June 7, 2005) WASHINGTON : 2005 STATISTICS OF THE PRESIDENTIAL AND CONGRESSIONAL ELECTION OF NOVEMBER 2, 2004 (Number which precedes name of candidate designates Congressional District. Since party names for Presidential Electors for the same candidate vary from State to State, the most commonly used name is listed in parentheses.) ALABAMA FOR PRESIDENTIAL ELECTORS Republican .................................................................................................. 1,176,394 Democratic .................................................................................................. 693,933 Independent ................................................................................................ 1 12,190 Write-in ....................................................................................................... 898 FOR UNITED STATES SENATOR Richard C. Shelby, Republican ................................................................. 1,242,200 Wayne Sowell, Democrat ........................................................................... 595,018 Write-in ...................................................................................................... -

Official Primary Election Ballot, August 30, 2016 Republican Party, Bay County, Florida

11 Official Primary Election Ballot, August 30, 2016 Republican Party, Bay County, Florida Instructions: To vote, fill in the oval completely ( ) next to your choice. Use only the marking device provided or a black or blue pen. If you make a mistake, ask for a new ballot. Do not cross out or your vote may not count. 21 United States Senator Board of County Commissioners (Vote for 1) District 3 Universal Primary Contest Carlos Beruff REP (Vote for 1) Ernie Rivera REP Bill Dozier REP Marco Rubio REP Steve Thomas REP Dwight Mark Anthony Young REP Board of County Commissioners Representative in Congress District 5 District 2 Universal Primary Contest (Vote for 1) (Vote for 1) Neal Dunn REP Philip "Griff" Griffitts REP 40 Ken Sukhia REP Brian Rust REP 41 Mary Thomas REP State Committeeman (Vote for 1) 42 State Attorney 14th Judicial Circuit 43 Universal Primary Contest John D. Salak REP (Vote for 1) James Waterstradt REP Glenn Hess REP State Committeewoman (Vote for 1) Greg Wilson REP State Representative Mitzi Prater REP District 5 (Vote for 1) Thelma Rohan REP Brad Drake REP No. 4 Constitutional Amendment, 51 Bev Kilmer REP Article VII, Sections 3 and 4, Article XII, Section 34 Property Appraiser Universal Primary Contest (Vote for 1) SOLAR DEVICES OR RENEWABLE ENERGY SOURCE DEVICES; Gregory LaPlante REP EXEMPTION FROM CERTAIN TAXATION AND ASSESSMENT. Dan Sowell REP Proposing an amendment to the State Constitution to authorize the Superintendent of Schools Legislature, by general law, to (Vote for 1) exempt from ad valorem taxation the assessed value of solar or renewable Bill Husfelt REP energy source devices subject to tangible personal property tax, and to Mackie Owens REP authorize the Legislature, by general law, to prohibit consideration of such devices in assessing the value of real Board of County Commissioners property for ad valorem taxation District 1 purposes. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 REAPPORTIONMENT PUBLIC HEARING 8 9 10 September 5, 2001 - 9:00 A.M

Page 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 REAPPORTIONMENT PUBLIC HEARING 8 9 10 September 5, 2001 - 9:00 A.M. 11 COURTHOUSE EXECUTIVE CENTER 12 2145 14TH AVENUE 13 VERO BEACH, FLORIDA 14 15 16 17 18 19 REPORTED BY: 20 JULIE L. DOHERTY, RPR 21 COURT REPORTER 22 Division of Administrative Hearings 23 DeSoto Building 24 1230 Apalachee Parkway 25 Tallahassee, Florida DIVISION OF ADMINISTRATIVE HEARINGS (850) 488-9675 Page 2 Page 4 1 MEMBERS IN ATTENDANCE 1 Following my brief remarks, counsel will give a 2 SENATOR LEE CONSTANTINE 2 general overview of legal considerations in redistricting. 3 SENATOR ANNA P. COWIN 3 Staff will then provide some specific information about the 4 SENATOR RON KLEIN 4 census results in this region and the state. The rest is 5 SENATOR DURELL PEADEN, JR. 5 reserved for you, the citizens. 6 SENATOR BILL POSEY 6 Every ten years after completion of the updated 7 SENATOR KEN PRUITT 7 national census, the Constitution requires the Florida 8 SENATOR DANIEL WEBSTER 8 Legislature to redraw boundaries of all the districts of 9 REPRESENTATIVE BOB ALLEN 9 the Florida House of Representatives, the Florida Senate 10 REPRESENTATIVE FRANK ATTKISSON 10 and Florida's Congressional districts. The Legislature 11 REPRESENTATIVE RANDY JOHN BALL 11 will take up this task in the next legislative session 12 REPRESENTATIVE GASTON I. CANTENS 12 which begins January 22nd, 2002 and ends March 22nd, 2002. 13 REPRESENTATIVE MARIO DIAZ-BALART 13 The districts we draw will first be used in the November 14 REPRESENTATIVE MIKE FASANO 14 2002 elections. -

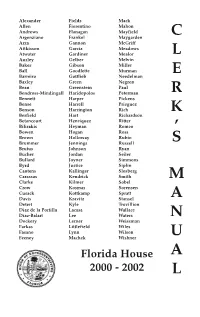

C L E R K ' S M a N U

Alexander Fields Mack Allen Fiorentino Mahon Andrews Flanagan Mayfield Argenziano Frankel Maygarden C Arza Gannon McGriff Attkisson Garcia Meadows Atwater Gardiner Mealor L Ausley Gelber Melvin Baker Gibson Miller Ball Goodlette Murman E Barreiro Gottlieb Needelman Baxley Green Negron Bean Greenstein Paul Bendross-Mindingall Haridopolos Peterman R Bennett Harper Pickens Bense Harrell Prieguez Benson Harrington Rich K Berfield Hart Richardson Betancourt Henriquez Ritter Bilirakis Heyman Romeo Bowen Hogan Ross ’ Brown Holloway Rubio Brummer Jennings Russell S Brutus Johnson Ryan Bucher Jordan Seiler Bullard Joyner Simmons Byrd Justice Siplin Cantens Kallinger Slosberg Carassas Kendrick Smith M Clarke Kilmer Sobel Crow Kosmas Sorensen Cusack Kottkamp Spratt Davis Kravitz Stansel A Detert Kyle Trovillion Diaz de la Portilla Lacasa Wallace Diaz-Balart Lee Waters N Dockery Lerner Weissman Farkas Littlefield Wiles Fasano Lynn Wilson Feeney Machek Wishner U Florida House A 2000 - 2002 L The Clerk's Manual 2000-2002 Compiled for use by The House of Representatives of the State of Florida John B. Phelps, Clerk of the House March 2001 Contents The House of Representatives House Directory....1 Members, by Districts....8 House Districts, by Counties....15 Councils and Committees....17 Members, Biographies....28 Other House Officers....186 Members, Length of Service....189 The Senate Senate Directory....194 Senators, by Districts....197 Senate Districts, by Counties....200 Committees....202 Senators, Biographies....209 Other Senate Officers....282 Senators, Seniority....284 Capitol Press Corps....286 The House of Representatives Tom Feeney, Speaker Sandra L. "Sandy" Murman, Speaker pro tempore Mike Fasano, Majority Leader Lois J. Frankel, Democratic Leader Doug Wiles, Democratic Leader pro tempore John B. -

Congressional Record—Senate S7169

June 22, 2004 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S7169 that diminish the effectiveness of the research whaling program, and do not H.R. 4589. An act to reauthorize the Tem- International Whaling Commission believe that imposing import prohibi- porary Assistance for Needy Families block (IWC) conservation program. This mes- tions would further our objectives. grant program through September 30, 2004, and for other purposes. sage constitutes my report to the Con- GEORGE W. BUSH. gress consistent with subsection (b) of THE WHITE HOUSE, June 22, 2004. f the Pelly Amendment. f MEASURES REFERRED The certification of the Secretary of Commerce is the first against Iceland MESSAGES FROM THE HOUSE The following bills were read the first for its lethal research whaling pro- At 2:53 a.m., a message from the and second times by unanimous con- gram. In 2003, Iceland announced that House of Representatives, delivered by sent, and referred as indicated: it would begin a lethal research whal- Ms. Niland, one of its reading clerks, H.R. 3706. An act to adjust the boundary of ing program and planned to take 250 announced that the House has passed the John Muir National Historic Site, and the following bills, in which it requests for other purposes; to the Committee on En- minke, fin, and sei whales for research ergy and Natural Resources. purposes. The United States expressed the concurrence of the Senate: H.R. 3751. An act to require that the Office strong opposition to Iceland’s decision, H.R. 884. An act to provide for the use and of Personnel Management study current in keeping with our longstanding pol- distribution of the funds awarded to the practices under which dental, vision, and icy against lethal research whaling. -

Cali Thinks It May Be a Good Idea Could the Draft Be Reinstituted

The Election Edition THE CelebratingH 84 years as the voice ofILL Leon. TOPMay, 2May, 2004004 Leon High School 550 E. Tennessee St. Tallahassee, FL 32308 (850) 488-1971 Vol. LXXXV No.4 Celebrating 85 years as the voice of Leon Should 14 year olds vote? Cali thinks it may be a good idea By Emily Woodruff The idea parallels a legally,” said sophomore Hill Top Features Editor burgeoning youth-vote Waylen Roche. movement both in the U.S. Sophomore Caroline As more and more and abroad. Britain has a Campbell agrees. companies take advantage formal proposal in Parlia- “Most 14- and 15- of the enthusiastic and ea- ment to lower the age to 16 year-olds don’t know what ger work ethic high and Germany is consider- they’re doing. They need schoolers provide at a low ing giving families as many to learn about how the gov- cost, students gain more votes as there are family ernment system works be- and more responsibility, members. Parts of Ger- fore they can become a taking on several aspects many and Austria allow vot- part of it,” said Campbell. of an adult life. They work ing at 16, and Israel’s vot- The Senators of around demanding sched- ing age is 17. California believe they ules, meet challenging With more and more are doing teens a favor by deadlines, and to the dis- countries contemplating increasing their power may of some, pay taxes. As youth voting, this issue may and influence in the high school students take soon turn local. Several of voting process, but the on the duties and respon- The phrase on this t-shirt may be proven wrong if the those who would be in- general consensus seems sibilities characteristic of bill is passed. -

The Journal of the House of Representatives

The Journal OF THE House of Representatives ORGANIZATION SESSION Tuesday, November 21, 2000 Journal of the House of Representatives for the Organization Session of the 80th House since Statehood in 1845, convened under the Constitution, begun and held at the Capitol in the City of Tallahassee in the State of Florida on Tuesday, November 21, 2000, being the day fixed by the Constitution for the purpose. John B. Phelps, the Clerk of the preceding session, delegated the 28—Suzanne M. Kosmas, New Smyrna Beach duties of temporary presiding officer to the Honorable John Thrasher, 29—Randy Ball, Mims retiring Speaker. Mr. Thrasher called the House to order at 10:00 a.m. 30—Mike Haridopolos, Melbourne 31—Mitch Needelman, Melbourne The following certified list of Members elected to the House of 32—Bob Allen, Rockledge Representatives was received: 33—Tom Feeney, Oviedo 34—David J. Mealor, Lake Mary State of Florida 35—Jim Kallinger, Winter Park 36—Allen Trovillion, Winter Park Office of Secretary of State 37—David Simmons, Longwood I, Katherine Harris, Secretary of State of the State of Florida, do 38—Frederick C. Brummer, Apopka hereby certify that the following Members of the House of 39—Gary Siplin, Orlando Representatives were elected at the General Election held on the 40—Andy Gardiner, Orlando Seventh day of November, A.D., 2000, as shown by the election returns 41—Randy Johnson, Celebration on file in this office: 42—Hugh Gibson, Lady Lake 43—Nancy Argenziano, Dunnellon HOUSE DISTRICT ELECTED MEMBERS 44—Dave Russell, Brooksville NUMBER 45—Mike Fasano, New Port Richey 1—Jeff Miller, Pace 46—Heather Fiorentino, New Port Richey 2—Jerry L. -

Official General Election Ballot Bay County, Florida November 7, 2000

Ballot Style 15 OFFICIAL GENERAL ELECTION BALLOT BAY COUNTY, FLORIDA NOVEMBER 7, 2000 TO VOTE, COMPLETE THE ARROW(S) POINTING TO YOUR CHOICE(S), LIKE THIS: INSTRUCTIONS CONGRESSIONAL COUNTY a. TO VOTE FOR a candidate whose name is printed on the UNITED STATES SENATOR CLERK OF THE CIRCUIT COURT ballot, complete the arrow (Vote for One) (Vote for One) pointing to the candidate for BILL McCOLLUM REP KEVIN E. WOOD REP whom you desire to vote. b. TO VOTE FOR a write-in BILL NELSON DEM HAROLD BAZZEL DEM candidate, you must write the JOE SIMONETTA LAW qualified candidate’s name in the PROPERTY APPRAISER space provided for write-ins and JOEL DECKARD REF (Vote for One) complete the arrow pointing to the write-in candidate. WILLIE LOGAN NPA RICK BARNETT REP c. Mark only with black felt tip pen or ANDY MARTIN NPA RICHARD J. DAVIS DEM No. 2 pencil. DARRELL L. McCORMICK NPA d. If you tear, deface or wrongly SUPERINTENDENT OF SCHOOLS mark this ballot, return it and get (Vote for One) another. REP WRITE-IN CANDIDATE CARL BENNETT ELECTORS FOR PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT U.S. REPRESENTATIVE JAMES E. McCALISTER DEM SECOND CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT (A vote for the candidates will actually (Vote for One) SUPERVISOR OF ELECTIONS be a vote for their electors) (Vote for One) DOUG DODD REP (Vote for Group) ALLEN BOYD DEM MARK ANDERSEN REP REPUBLICAN GEORGE W. BUSH, For President MELANIE WILLIAMS BOYD DEM DICK CHENEY, For Vice President COUNTY COMMISSIONER DEMOCRATIC WRITE-IN CANDIDATE DISTRICT 1 AL GORE, For President (Vote for One) JOE LIEBERMAN, For Vice President