510 Main Street Winnipeg City Hall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winnipeg's Water Treatment Could Be Privatized

Members of Council PEOPLE TAKE ACTION TO PROTECT WATER His Worship Mayor Sam Katz A coalition of community, student, faith, environment 986-5665 and union groups are campaigning to protect public www.winnipeg.ca water. These groups want the City to consult the public on water related issues. They are educating the public about the dangers of WARD/ PHONE COUNCILLOR privatizing water and lobbying politicians to keep NUMBER water a public resource. Jeff Browaty North Kildonan [email protected] 986-5196 SPEAK OUT! Bill Clement Charleswood – Tuxedo We are encouraging everyone to speak out about [email protected] 986-5232 the importance of public water: You can: Scott Fielding St James – Brooklands • contact your Councillor [email protected] 986-5848 • post this brochure in your workplace or Jenny Gerbasi Fort Rouge - E. Fort Garry share it with a friend [email protected] 986-5878 Harry Lazarenko Mynarski STAY INFORMED! [email protected] 986-5188 Sign-up for email updates and stay informed about John Orlikow River Heights - Fort Garry action taking place to keep water public. It’s easy to [email protected] 986-5236 join. Go to www.cupe500.mb.ca and click on the Grant Nordman St. Charles “sign-up” button. [email protected] 986-5920 Mike O’Shaughnessy Old Kildonan For more information and resources about water, [email protected] 986-5264 visit: Mike Pagtakhan Point Douglas Council of Canadians: www.canadians.org/water/ [email protected] 986-8401 Canadian Union of Public Employees: www.cupe.ca/water Harvey Smith Daniel McIntyre [email protected] 986-5951 Inside the Bottle: www.insidethebottle.org/ Gord Steeves St. -

The Value of Investing in Canadian Downtowns Part 2

REGINA A new era Snap Shot of Regina Provincial capital of Saskatchewan Experiencing one of the fastest economic growth rates in Canada Downtown is poised for a large increase in population A compact and dense urban core with an impressive skyline, for a city of its size There are few physical constraints when it comes to urban expansion Regina is presently experiencing some of the fastest economic growth in Canada, and the downtown is poised to undergo a period of rapid change in the coming decades. In preparation for this growth, the City has undertaken an “Regina has a very small, very extensive downtown master planning process that contained downtown this is a – recognizes the importance of the core and envisages it tremendous positive when it emerging as an increasingly vital, mixed use and walkable comes to experiencing the neighbourhood. The City has also created a range of downtown environment.” financial incentives, policy tools and invested in public projects to accelerate downtown revitalization efforts. Despite these positive steps, downtown Regina remains challenged to attract its share of growth and investment in an expanding urban region, achieve high quality urban design, enhance its heritage buildings, and attract residential growth to increase its critical mass of activity beyond business hours. On the whole, Regina is placing greater value on its downtown, but long term commitment to intensification efforts will be required to realize the urban vision set out for the downtown core into the future. 53 Downtown Regina Timeline 1881: Edward Carss, one of the first 1882 – Regina, named for Queen Victoria, European pioneers in the Regina area, is established as the capital of the North- settled at the junction of Qu’Appelle River West Territory near the site of an earlier and Wascana Creek. -

2. the Capital Budget Winnipeg's

Contributors This guide is the first Betty Braaksma step in a four-part Manitoba Library Association Canadian Centre for Policy Marianne Cerilli Social Planning Council of Winnipeg Alternatives-Manitoba Lynne Fernandez (CCPA-Mb) project to Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, Manitoba engage Winnipeggers in Jesse Hajer Canadian Community Economic Development municipal decision-making. Network Step Two is a survey of George Harris key municipal spending Ian Hudson Department of Economics areas, Step Three will be an University of Manitoba in-depth response to this Bob Kury spring’s 2008 Operating Dennis Lewycky CCPA Board Member Budget, and Step Four will Lindsey McBain be our Alternative City Canadian Community Economic Development Network Budget, to be released in Tom Simms the fall of 2008. Many thanks to Liz Carlye of the Canadian Federation of Students CANADIAN CENTRE FOR POLICY (Manitoba) and Doug Smith for their ALTERNATIVES-MB help with production. 309-323 Portage Ave. Winnipeg, MB Canada R3B 2C1 ph: (204) 927-3200 fax: (204) 927-3201 [email protected] www.policyalternatives.ca A Citizens’ Guide to Understanding Winnipeg’s City Budgets 1 Introduction innipeg City Council spends more than one billion dollars a year running our city. From the moment we get up in the morning, most of us benefit from the Wservices that our taxes provide. We wash up with water that is piped in through a city-built and operated water works, we walk our children to school on city sidewalks, go to work on city buses, drive on city streets that have been cleared of snow by the City. -

Cultural Heritage Impact Statement Ottawa Public Library/Library and Archives Canada Joint Facility 555 Albert Street, Ottawa, ON

Cultural Heritage Impact Statement Ottawa Public Library/Library and Archives Canada Joint Facility 555 Albert Street, Ottawa, ON Prepared for: Ralph Wiesbrock, OAA, FRAIC, LEED AP Partner / Principal KWC Architects Inc. 383 Parkdale Avenue, suite 201 Ottawa, Ontario K1Y 4R4 T: 613-238-2117 ext. 225 C: 613-728-5800 E: [email protected] Submitted by: Julie Harris, CAHP, Principal & Heritage Specialist, Contentworks Inc. E: [email protected] T: 613 730-4059 Date: 17 June 2020 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 ABOUT THE CHIS ........................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 SOURCES .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 DEVELOPMENT SITE ...................................................................................................................................... 3 2 HERITAGE RESOURCE DESCRIPTIONS AND HISTORIES ........................................................ 9 2.1 FORMAL MUNICIPAL RECOGNITIONS .......................................................................................................... 9 2.2 OTHER HERITAGE ....................................................................................................................................... 18 3 PROPOSED -

Winnipeg's Housing Crisis and The

Class, Capitalism, and Construction: Winnipeg’s Housing Crisis and the Debate over Public Housing, 1934–1939 STEFAN EPP* The collapse of the construction industry during the 1930s resulted in a housing crisis of unprecedented proportions in cities throughout Canada. Winnipeg faced a particularly difficult situation. Beginning in 1934, the city undertook several endeavours to remedy the problem, all of which failed. While the shortcomings of federal housing programmes and reluctant federal and provincial governments were partly to blame for the failure of these local efforts, municipal debates on the subject of housing reveal that reform was also stalled by opposition from the local business elite, whose members disliked competition in the rental market. L’effondrement de l’industrie de la construction dans les anne´es 1930 a provoque´ une crise sans pre´ce´dent du logement dans les villes du Canada. La situation e´tait particulie`rement difficile a` Winnipeg. En 1934, la ville a commence´ a` prendre des mesures pour corriger le proble`me : toutes ont e´choue´. Si les faiblesses des pro- grammes fe´de´raux de logement et la re´ticence des gouvernements fe´de´ral et provin- cial ont contribue´ partiellement a` l’e´chec de ces efforts locaux, les de´bats municipaux sur la question du logement re´ve`lent que la re´forme s’est e´galement heurte´ea` l’opposition de l’e´lite locale du milieu des affaires, dont les membres n’aimaient pas la concurrence sur le marche´ locatif. DURING THE 1930s, Canadian cities struggled to cope with a significant housing shortage. -

Drawer Inventory Combined G

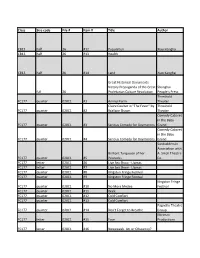

Class Size code File # Item # Title Author CB13 half 26 #12 Population Xiao Hangha CB13 half 26 #13 Health CB13 half 26 #14 Land Xiao Kanghai Great Historical Documents - Victory Propaganda of the Great Shanghai full 26 Proletarian Culture Revolution People's Press Threshold FC177 quarter 020C1 #1 Animal Farm Theater Claire Coulter in "The Fever" by Threshold FC177 quarter 020C1 #2 Wallace Shawn Theater Comedy Cabaret in the Baby FC177 quarter 020C1 #3 Serious Comedy for Oxymorons Grand Comedy Cabaret in the Baby FC177 quarter 020C1 #4 Serious Comedy for Oxymorons Grand Sunbuilders in Association with Brilliant Turquoise of her A. Small Theatre FC177 quarter 020C1 #5 Peacocks Co. FC177 letter 020C1 #6 Live Sex Show - Llamas FC177 letter 020C1 #7 Live Sex Show - Llamas FC177 quarter 020C1 #8 Kingston Fringe Festival FC177 quarter 020C1 #9 Kingston Fringe Festival Kingston Fringe FC177 quarter 020C1 #10 No More Medea Festival FC177 quarter 020C1 #11 Walk FC177 quarter 020C1 #12 Cold Comfort FC177 quarter 020C1 #13 Cold Comfort Pagnello Theatre FC177 quarter 020C1 #14 Don't Forget to Breathe Group Mirimax FC177 letter 020C1 #15 Face Productions FC177 letter 020C1 #16 Newsweek. Art or Obscenity? Month of Sundays, Broadway Bound, A Night at the Grand, Baby Fringe FC177 quarter 020C1 #17 Sex and Politics Theatre Festival FC177 quarter 020C1 #18 Shaking Like a Leaf FC177 quarter 020C1 #19 Bent FC177 quarter 020C1 #20 Bent FC177 quarter 020C1 #21 Kennedy's Children FC177 quarter 020C1 #22 Dumbwaiter/Suppress FC177 letter 020C1 #23 Bath Haydon Theatre Kingston Fringe FC177 quarter 020C1 #24 Using Festival West of Eden FC177 quarter 020C1 #25 Big Girls Don't Cry Production Two One Act Plays: "Winners" A. -

Ourwinnipeg.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE SECTION PAGE Introduction – It’s Our City, It’s Our Plan, 02 A Sustainable City 64 It’s Our Time 02 02–1 Sustainability 65 OurWinnipeg: Context + Opportunities 06 02–2 Environment 68 The Vision for OurWinnipeg 20 02–3 Heritage 69 The OurWinnipeg Process: SpeakUpWinnipeg 21 03 Quality of Life 72 01 A City That Works 24 03–1 Opportunity 73 01–1 City Building 25 03–2 Vitality 79 01–2 Safety and Security 41 03–3 Creativity 83 01–3 Prosperity 48 04 Implementation 88 01–4 Housing 54 Glossary 94 01–5 Recreation 58 01–6 Libraries 61 01 INTITRODUC ON IT’S OUR CITY, IT’S OUR PLAN, IT’S OUR TIME. The majority of the world’s people now live in cities, and OurWinnipeg, the City’s new municipal development urban governments are on the forefront of the world’s plan, answers these questions and positions Winnipeg development and economy. More than ever before, cities are for sustainable growth, which is key to our future the leading production centres for culture and innovation, competitiveness. It sets a vision for the next 25 years and are the leaders on global issues like climate change, and, if provides direction in three areas of focus–each essential they are to compete successfully for sustainable growth, are to Winnipeg’s future: required to deliver a high quality of life. A CITY THAT WORKS Winnipeg is no exception to this dynamic. We are now Citizens choose cities where they can prosper and enjoy competing, on a global scale, for economic development a high quality of life. -

Municipal Manual 2004 Manitoba Cataloguing in Publication Data

Municipal Manual 2004 Manitoba Cataloguing in Publication Data Winnipeg (Man.). Municipal Manual - 1904 - Also available in French Prepared by the City Clerk’s Dept. Issn 0713 = Municipal Manual - City of Winnipeg. 1. Administrative agencies - Manitoba - Winnipeg - Handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. Executive departments - Manitoba - Winnipeg - Handbooks, manuals, etc. 3. Winnipeg (Man.). City Council - Handbooks, manuals, etc. 4. Winnipeg (Man.) - Guidebooks. 5. Winnipeg (Man.) - Politics and government - Handbooks, manuals, etc. 6. Winnipeg (Man.) - Politics and government - Directories. I. Winnipeg (Man.). City Clerk’s Department. JS1797.A13 352.07127’43 Cover Photograph: The Provencher Twin Bridge and the Pedestrian walkway known as “Esplanade Riel”. The dramatic cable-stayed pedestrian bridge is Winnipeg’s newest landmark, and was officially opened on December 31, 2003. The Cover Photo was taken by Winnipeg Sun photographer, John Woods and is used with permission from the Toronto Sun Publishing Company. All photographs contained within this manual are the property of the City of Winnipeg Archives, the City of Winnipeg and the City Clerk’s Department. Permission to reproduce must be requested in writing to the City Clerk’s Department, Council Building, City Hall, 510 Main Street, Winnipeg, MB, R3B 1B9. The City Clerk’s Department gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the Creative Services Branch in producing this document. Table of Contents Introduction 3 Preface 4A Message from the Mayor 5A Message from the Chief Administrative Officer -

City of Winnipeg 2019 Preliminary Budget

2019 Preliminary Budget OPERATING AND CAPITAL Volume 2 City of Winnipeg 2019 Preliminary Budget Operating and Capital Volume 2 WINNIPEG, MANITOBA, CANADA The City of Winnipeg Winnipeg, Manitoba R3B 1B9 Telephone Number: 311 Toll Free : 1-877-311-4WPG(4974) www.winnipeg.ca Government Finance Officers Association of the United States and Canada (GFOA) presented a Distinguished Budget Presentation Award to City of Winnipeg, Manitoba, for its Annual Budget for the fiscal year beginning January 1, 2018. In order to receive this award, a governmental unit must publish a budget document that meets program criteria as a policy document, as a financial plan, as an operations guide and as a communications device. This award is valid for a period of one year only. We believe our current budget continues to conform to program requirements, and we are submitting it to GFOA to determine its eligibility for another award. i ii City of Winnipeg Council Mayor Brian Bowman Matt Allard Jeff Browaty Markus Chambers Ross Eadie Scott Gillingham ST. BONIFACE NORTH KILDONAN ST. NORBERT - MYNARSKI ST. JAMES Acting Deputy Mayor SEINE RIVER Deputy Mayor Cindy Gilroy Kevin Klein Janice Lukes Brian Mayes Shawn Nason DANIEL MCINTYRE CHARLESWOOD - WAVERLEY WEST ST. VITAL TRANSCONA TUXEDO - WESTWOOD John Orlikow Sherri Rollins Vivian Santos Jason Schreyer Devi Sharma RIVER HEIGHTS - FORT ROUGE - POINT DOUGLAS ELMWOOD - EAST OLD KILDONAN FORT GARRY EAST FORT GARRY KILDONAN iii City of Winnipeg Organization APPENDIX “A” to By-law No. 7100/97 amended 143/2008; 22/2011; -

Winnipeg's Civil Political History and the Logic of Structural Urban Reform: a Review Article P

Document generated on 09/27/2021 9:22 a.m. Urban History Review Revue d'histoire urbaine Winnipeg's Civil Political History and the Logic of Structural Urban Reform: A Review Article P. H. Wichern Number 1-78, June 1978 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1019444ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1019444ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine ISSN 0703-0428 (print) 1918-5138 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Wichern, P. H. (1978). Review of [Winnipeg's Civil Political History and the Logic of Structural Urban Reform: A Review Article]. Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine, (1-78), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.7202/1019444ar All Rights Reserved © Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine, 1978 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Ill BOOK REVIEWS •k ic ic ic "k ic "k WINNIPEG1S CIVIC POLITICAL HISTORY AND THE LOGIC OF STRUCTURAL URBAN REFORM: A REVIEW ARTICLE The fascinating history of Winnipeg's development as a Canadian metropolis is only beginning to attract the public and scholarly attention which it so obviously deserves- In terms of official public concern, Winnipeg is still at a nascent stage, having no formal City Archives in spite of the $750,000 spent on the City's Centennial activities in 1974, and a new Centennial Library subsequently built downtown. -

Winnipeg: Aspirational Planning, Chaotic Development

WINNIPEG: ASPIRATIONAL PLANNING, CHAOTIC DEVELOPMENT by Christopher Leo University of Winnipeg ABSTRACT This paper looks at the politics of development in suburban and exurban Winnipeg, showing how the reality of chaotic development is glossed over by specious planning language. Drawing on case studies of two undeveloped or newly-developing areas of the central city, Transcona West and Waverley West, and a developing exurb, Springfield Municipality, the paper shows how municipal infrastructure and services are extended widely and inefficiently across the region in response to developers’ demands, and wishful thinking conceals the reality of an unviable network. The city is left with infrastructure and municipal services whose lack of viability becomes manifest in the city’s inability to maintain inner- city streets and underground municipal services. 2 WINNIPEG: ASPIRATIONAL PLANNING, CHAOTIC DEVELOPMENT Introduction Urban sprawl has long been a major preoccupation of the literature on North American urban development. In that literature, a distressing amount of attention has been devoted to definitional discussions, but in these pages, we will skirt that terrain and proceed by diktat, defining sprawl as low-density, single-use development: neighbourhoods or sections of cities marked by exclusivity, not only of residential, commercial, industrial or agricultural land uses, but also of low, medium and high densities, and light and heavy commercial and industrial development. In the world of sprawl, these multiple exclusivities are further multiplied by the definition of particular design types, residential wealth gradations, and other specificities of land use. Much of the literature on sprawl is critical of many of these varieties of exclusivity, maintaining that they kill urbanity, choke off street life and mandate environmentally harmful dependence on automobiles. -

The Winnipeg Labour Council 1894-1994: a Century of Labour

THE 1894-1994: A CENTURY OF WINNIPEG LABOUR EDUCATION, LABOUR ORGANIZATION COUNCIL AND AGITATION MANITOBA LABOUR HISTORY SERIES 2 Manitoba Labour History Series The working people of Manitoba are the inspiration for this volume. The Committee on Manitoba’s Labour History, a group of trade unionists and labour historians has supervised the selec- tion and publication of illustrated books and booklets since 1985. Each title portrays a different aspect of Manitoba’s labour history. It is the Committee’s hope that these publications will make all Manitobans more aware of the vital contributions made to the life of this province by the women and men who worked on the farms and in the mines, mills, factories, cities, towns, homes and offices of Manitoba. Jim Naylor (Chair) Ken Osborne Nolan Reilly Edith Burley John Pullen Larry Gagnon Gerry Friesen Terry Kennedy PREFACE TABLE OF 1994 marked the 75th anniversary of the Winnipeg General Strike. In Manitoba the labour movement commemorated that CONTENTS event with a wide variety of events. However, it also marked the 100th anniversary of the Winnipeg Labour Council. The Coun- cil organized the strike, and nearly self-destructed after the strike was broken. This booklet was commissioned to remind THE STORY Winnipeggers that the labour movement is no flash in the pan in this province’s history. For over a century unions have been Labour Days 3 struggling to improve working conditions, and through organi- Workers’ Compensation 6 zations like the Council, to provide workers with a forum to War and the General Strike 7 debate issue of importance to labour and with, as one person quoted in this book commented, “a mighty arm” to bring about 1919 8 political and social change.