How Immigrants Contribute to Developing Countries’ Economies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Globalization, Immigration, and Education: Recent Us Trends

MASTER GABRIELLA.qxd:09_Suarez-Orozco(OK+Ale).qxd 12-12-2006 16:55 Pagina 93 Globalization and Education Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences, Extra Series 7, Vatican City 2006 www.pass.va/content/dam/scienzesociali/pdf/es7/es7-suarezorozco.pdf GLOBALIZATION, IMMIGRATION, AND EDUCATION: RECENT US TRENDS MARCELO SUÁREZ-OROZCO, CAROLA SUÁREZ-OROZCO Over the last decade globalization has intensified worldwide economic, social, and cultural transformations. Globalization is structured by three powerful, interrelated formations: 1) the post-nationalization of produc- tion, distribution, and consumption of goods and services – fueled by grow- ing levels of international trade, foreign direct investment, and capital mar- ket flows; 2) the emergence of new information, communication, and media technologies that place a premium on knowledge intensive work, and 3) unprecedented levels of world-wide migration generating significant demographic and cultural changes in most regions of the world. Globalization’s puzzle is that while many applaud it as the royal road for development (see, for example, Micklethwait & Wooldrige, 2000; Friedman, 2000, Rubin 2002) it is nevertheless generating strong currents of discon- tent. It is now obvious that in large regions of the world, globalization has been a deeply disorienting and threatening process of change (Stiglitz, 2002; Soros, 2002; Bauman, 1998). Globalization has generated the most hostili- ties where it has placed local cultural identities, including local meaning sys- tems, local religious identities, and local systems of livelihood, under siege. Argentina is a case in point. After a decade of cutting-edge free market poli- cies, the economy of the country that once was the darling of such embodi- ments of globalization as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, imploded. -

IMMIGRATION LAW BASICS How Does the United States Immigration System Work?

IMMIGRATION LAW BASICS How does the United States immigration system work? Multiple agencies are responsible for the execution of immigration laws. o The Immigration and Naturalization Service (“INS”) was abolished in 2003. o Department of Homeland Security . USCIS . CBP . ICE . Attorney General’s role o Department of Justice . EOIR . Attorney General’s role o Department of State . Consulates . Secretary of State’s role o Department of Labor . Employment‐related immigration Our laws, while historically pro‐immigration, have become increasingly restrictive and punitive with respect to noncitizens – even those with lawful status. ‐ Pro‐immigration history of our country o First 100 Years: 1776‐1875 ‐ Open door policy. o Act to Encourage Immigration of 1864 ‐ Made employment contracts binding in an effort to recruit foreign labor to work in factories during the Civil War. As some states sought to restrict immigration, the Supreme Court declared state laws regulating immigration unconstitutional. ‐ Some early immigration restrictions included: o Act of March 3, 1875: excluded convicts and prostitutes o Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882: excluded persons from China (repealed in 1943) o Immigration Act of 1891: Established the Bureau of Immigration. Provided for medical and general inspection, and excluded people based on contagious diseases, crimes involving moral turpitude and status as a pauper or polygamist ‐ More big changes to the laws in the early to mid 20th century: o 1903 Amendments: excluded epileptics, insane persons, professional beggars, and anarchists. o Immigration Act of 1907: excluded feeble minded persons, unaccompanied children, people with TB, mental or physical defect that might affect their ability to earn a living. -

The Czech Republic: on Its Way from Emigration to Immigration Country

No. 11, May 2009 The Czech Republic: on its way from emigration to immigration country Dušan Drbohlav Department of Social Geography and Regional Development Charles University in Prague Lenka Lachmanová-Medová Department of Social Geography and Regional Development Charles University in Prague Zden ěk Čermák Department of Social Geography and Regional Development Charles University in Prague Eva Janská Department of Social Geography and Regional Development Charles University in Prague Dita Čermáková Department of Social Geography and Regional Development Charles University in Prague Dagmara Dzúrová Department of Social Geography and Regional Development Charles University in Prague Table of contents List of Tables .............................................................................................................................. 3 List of Figures ............................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 6 1. Social and Migration Development until 1989 ...................................................................... 7 1.1. Period until the Second World War ................................................................................ 7 1.2. Period from 1945 to 1989 .............................................................................................. 10 2. Social and Migration Development in the Period -

The Immigration Paradox: Poverty, Distributive Justice, and Liberal Egalitarianism

DePaul Law Review Volume 52 Issue 3 Spring 2003: Symposium - Beyond Belonging: Challenging the Boundaries of Article 2 Nationality The Immigration Paradox: Poverty, Distributive Justice, and Liberal Egalitarianism Howard F. Chang Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation Howard F. Chang, The Immigration Paradox: Poverty, Distributive Justice, and Liberal Egalitarianism, 52 DePaul L. Rev. 759 (2003) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol52/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMMIGRATION PARADOX: POVERTY, DISTRIBUTIVE JUSTICE, AND LIBERAL EGALITARIANISM Howard F. Chang* INTRODUCTION According to the 2000 Census, the foreign-born population in the United States reached 31.1 million, representing 11.1% of the total U.S. population.' This percentage is the highest that the United States has experienced since 1930, when 11.6% of the total U.S. popu- lation was foreign born.2 In 1970, the foreign-born population was only 9.6 million, or only 4.7% of the total population.3 The rapid ex- pansion of the foreign-born population in the intervening three de- 4 cades reflects high levels of immigration into the United States, which in turn reflects the liberalization of U.S. immigration laws since 1965. 5 Some observers have reacted to these data with alarm, noting that the sheer number of immigrants now residing in the United States is "by far the most ever recorded.' ' 6 The restrictionist Center for Im- migration Studies (CIS), for example, notes that the foreign-born pop- ulation grew by 11.3 million between 1990 and 2000, and that "[t]he foreign-born population's growth rate in every decade since 1970 has 7 been higher than at any other time in history." The absolute number of immigrants, however, is far less important than their share of the total U.S. -

Strategies in an Arts Program for Adults with Atypical Communication

STRATEGIES IN AN ARTS PROGRAM FOR ADULTS WITH ATYPICAL COMMUNICATION STRATEGIES AND ADAPTATIONS IN AN ARTS PROGRAM FOR ADULTS WITH ATYPICAL COMMUNICATION A Master’s Degree Thesis by Christina Lukac to Moore College of Art & Design In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MA in Art Education with an Emphasis in Special Populations Philadelphia, PA August 2017 Accepted: ________________________________ Lauren Stichter | Graduate Program Director Masters in Art Education with an Emphasis in Special Populations STRATEGIES IN AN ARTS PROGRAM FOR ADULTS WITH ATYPICAL ii COMMUNICATION Abstract The purpose of this study was to observe and implement strategies and adaptations in an arts program for adults with atypical communication due to developmental and intellectual disabilities. This study was conducted in the field using an action research approach with triangulated methods of data collection including semi- structured interviews, participant observations, and artwork analysis. While research was conducted in two different art programs with similar populations, the main site of study was at SpArc Service’s Cultural Arts Center located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The secondary site was at Center for Creative Works located in Wynnewood, Pennsylvania. The data collected between these sites produced common trends in strategies and adaptations that are used in the art room. Individual case studies conducted at SpArc Services allowed strategies to be implemented and documented in the art room. When implementing these findings, I saw how these strategies supported the participant’s goals as outlined in their Individual Outcome Summary. While working with the individual participants, areas of art making included textiles, mixed-media materials, and pop culture references. -

What Triggers Public Opposition to Immigration? Anxiety, Group Cues, and Immigration Threat

What Triggers Public Opposition to Immigration? Anxiety, Group Cues, and Immigration Threat Ted Brader University of Michigan Nicholas A. Valentino The University of Texas at Austin Elizabeth Suhay University of Michigan We examine whether and how elite discourse shapes mass opinion and action on immigration policy. One popular but untested suspicion is that reactions to news about the costs of immigration depend upon who the immigrants are. We confirm this suspicion in a nationally representative experiment: news about the costs of immigration boosts white opposition far more when Latino immigrants, rather than European immigrants, are featured. We find these group cues influence opinion and political action by triggering emotions—in particular, anxiety—not simply by changing beliefs about the severity of the immigration problem. A second experiment replicates these findings but also confirms their sensitivity to the stereotypic consistency of group cues and their context. While these results echo recent insights about the power of anxiety, they also suggest the public is susceptible to error and manipulation when group cues trigger anxiety independently of the actual threat posed by the group. mmigration surged onto the national agenda follow- tervals throughout U.S. history (Tichenor 2002). Current ing the 2004 election, as politicians wrangled over episodes reflect mounting pressures from heavy immi- I reforms on what is perceived to be a growing prob- gration and an expanding Latino electorate. West Europe lem for the United States (U.S.). Public concern followed, also has experienced a rising tide of migrants, spurring with 10% of Americans by 2006 naming it the most im- bitter debates over how to deal with the newcomers and portant problem facing the country, the highest level in 20 a growth in electoral position taking (Fetzer 2000; Sni- years of polling by Pew Research Center. -

Globalization, Immigration, and Cultural Change: Conditions That Predict Shifts in Nationalistic Attitudes

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 2020 Globalization, Immigration, and Cultural Change: Conditions that Predict Shifts in Nationalistic Attitudes Kelly Trail Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Trail, Kelly, "Globalization, Immigration, and Cultural Change: Conditions that Predict Shifts in Nationalistic Attitudes" (2020). Dissertations. 1809. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1809 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GLOBALIZATION, IMMIGRATION, AND CULTURAL CHANGE: CONDITIONS THAT PREDICT SHIFTS IN NATIONALISTIC ATTITUDES by Kelly Brannan Trail A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Social Science and Global Studies at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved by: Dr. Robert Pauly, Committee Chair Dr. Robert Press Dr. Julie Reid Dr. Thomas Lansford August 2020 COPYRIGHT BY Kelly Brannan Trail 2020 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT Globalization is on the rise across the globe. In many instances, nationalism appears to be, too, as evidenced by the anti-immigrant and “nation first” rhetoric and success of presidential candidates, such as Donald Trump in the United States and Sebastian Pinera in Chile. However, the author questioned whether nationalistic attitudes are truly on the rise across the globe and what conditions cause some countries to shift toward nationalistic attitudes in the face of rising globalization, while others to shift away from it. -

2 the Idea.Pages

THE IDEA ‘Sure I’ve got a minute. What’s your series about?’ Imagine this: through luck or perseverance, you have tracked down the exact producer you want to meet. You’ve done your homework. You know exactly who this person is, what shows they made and why they are perfect to executive produce your series. You’ve got them on the phone or you’ve planted yourself directly in their path outside a screening. However it happens, you’ve got their attention. For about a minute. How you use that minute will determine whether you are invited to come in for a meeting, or whether that producer will excuse themselves with a polite, ‘good luck.’ So what do we say? How do we best answer this basic question: ‘What is your series about?’ I’m going to give you a formula for this in a minute, but before I do, it’s important that you understand that there are at least two levels of communication going on in this situation. There is the WHAT (i.e., basic information that describes your series) and there is the HOW (i.e., the level of confidence and professionalism with which you speak). Which of these two do you think matters most at the outset? You don’t need to be a deep student of psychology or interpersonal relations to know that confidence is crucial in a situation like this. How you communicate matters tremendously. And yet, where is this confidence supposed to come from? You, someone who has never made a tv series? Perhaps never even staffed or written a pilot – how are you supposed to convey the confidence and authority to make this person comfortable enough to trust you? It’s actually pretty simple: practice. -

Teen-Targeted Broadcast TV Can Be Vulgar… but Stranger Things Are

Teen-Targeted Broadcast TV Can Be Vulgar… But Stranger Things Are Happening On Netflix EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The entertainment industry has, for decades, The Parents Television Council renews its call for cautioned parents who want to protect their children wholesale reform to the entertainment industry- from explicit content to rely on the various age- controlled ratings systems and their oversight. based content ratings systems. The movie industry, There should be one uniform age-based content the television industry, the videogame industry rating system for all entertainment media; the and the music industry have, individually, crafted system must be accurate, consistent, transparent medium-specific rating systems as a resource to and accountable to those for whom it is intended to help parents. serve: parents; and oversight of that system should be vested primarily in experts outside of those who In recent years, the Parents Television Council has produce and/or distribute the programming – and produced research documenting a marked increase who might directly or indirectly profit from exposing in profanity airing on primetime broadcast television. children to explicit, adult-themed content. All of the television programming analyzed by the PTC for those research reports was rated as appropriate for children aged 14, or even younger. Today, with much of the nation ostensibly on lockdown as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, children are at home instead of at school; and as a result, they have far greater access to entertainment media. While all forms of media consumption are up, the volume of entertainment programming being consumed through over-the-top streaming platforms has spiked dramatically. -

(IOM) (2019) World Migration Report 2020

WORLD MIGRATION REPORT 2020 The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. This flagship World Migration Report has been produced in line with IOM’s Environment Policy and is available online only. Printed hard copies have not been made in order to reduce paper, printing and transportation impacts. The report is available for free download at www.iom.int/wmr. Publisher: International Organization for Migration 17 route des Morillons P.O. Box 17 1211 Geneva 19 Switzerland Tel.: +41 22 717 9111 Fax: +41 22 798 6150 Email: [email protected] Website: www.iom.int ISSN 1561-5502 e-ISBN 978-92-9068-789-4 Cover photos Top: Children from Taro island carry lighter items from IOM’s delivery of food aid funded by USAID, with transport support from the United Nations. © IOM 2013/Joe LOWRY Middle: Rice fields in Southern Bangladesh. -

AN EXAMINATION of EMILY DICKINSON THESIS Presented To

310071 EMILY AND THE CHILD: AN EXAMINATION OF THE CHILD IMAGE IN THE WORK OF EMILY DICKINSON THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Nancy Eubanks McClaran, B. A. Denton, Texas May, 1974 ABSTRACT mcClaran, Nancy Eubanks, Emily and the Child.: An Examination of the Child Image in the Work of Emily Dickinson. Master of Arts (English), May, 1974, 155 pp., 6 chapters, bibliography 115 titles. The primary sources for this study are Dickinson's poems and letters. The purpose is to examine child imagery in Dickinson's work, and the investigation is based on the chronological age of children in the images. Dickinson's small child exists in mystical communion with nature and deity. Inevitably the child is wrenched from this divine state by one of three estranging forces: adult society, death, or love. After the estrangement the state of childhood may be regained only after death, at which time the soul enters immortality as a small child. The study moreover contends that one aspect of Dickinson's seclusion was an endeavor to remain a child. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 1 II. INFANCY - .-- -. * . 21 III. EARLY CHILDHOOD: EARTH'S CONFIDING TIME * " 0 27 IV. THE PROCESSOF ESTRANGEMET . ... 64 V. THE ESTRANGED CHILD ...--...... " 0 0 123 VI. CHILDHOOD IN MORTALITY . 134 BIBLIOGRAPHY 0 0-- 0 -- 40.. .. .. " 0 0 156 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION The poetry of Emily Dickinson has great significance in a study of imagery. Although that significance seemed apparent to critics almost from the moment the first volume of her poems was posthumously published in 1890, very little has been written on Dickinson's imagery. -

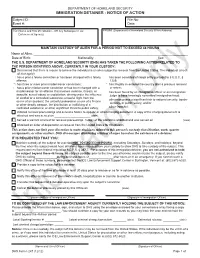

IMMIGRATION DETAINER - NOTICE of ACTION Subject ID: File No: Event #: Date

DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY IMMIGRATION DETAINER - NOTICE OF ACTION Subject ID: File No: Event #: Date: TO: (Name and Title of Institution - OR Any Subsequent Law FROM: (Department of Homeland Security Office Address) Enforcement Agency) MAINTAIN CUSTODY OF ALIEN FOR A PERIOD NOT TO EXCEED 48 HOURS Name of Alien: _____________________________________________________________________________________ Date of Birth: _________________________ Nationality: __________________________________ Sex: ____________ THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY (DHS) HAS TAKEN THE FOLLOWING ACTION RELATED TO THE PERSON IDENTIFIED ABOVE, CURRENTLY IN YOUR CUSTODY: Determined that there is reason to believe the individual is an alien subject to removal from the United States. The individual (check all that apply): has a prior a felony conviction or has been charged with a felony has been convicted of illegal entry pursuant to 8 U.S.C. § offense; 1325; has three or more prior misdemeanor convictions; has illegally re-entered the country after a previous removal has a prior misdemeanor conviction or has been charged with a or return; misdemeanor for an offense that involves violence, threats, or has been found by an immigration officer or an immigration assaults; sexual abuse or exploitation; driving under the influence judge to have knowingly committed immigration fraud; of alcohol or a controlled substance; unlawful flight from the otherwise poses a significant risk to national security, border scene of an accident; the unlawful possession or use of a firearm security, or public safety; and/or or other deadly weapon, the distribution or trafficking of a other (specify): __________________________________. controlled substance; or other significant threat to public safety; Initiated removal proceedings and served a Notice to Appear or other charging document.