ERITREA: Future Transitions and Regional Impacts / July 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eritrea RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: March 2018

Eritrea RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: March 2018 KNOWYOURCOUNTRY.COM Executive Summary - Eritrea Sanctions: UN and EU Financial and Arms embargo FAFT list of AML No Deficient Countries Compliance with FATF 40 + 9 Recommendations (mutual evaluation Higher Risk Areas: not yet completed) Weakness in Government Legislation to combat Money Laundering Not on EU White list equivalent jurisdictions Corruption Index (Transparency International & W.G.I.)) World Governance Indicators (Average Score) Failed States Index (Political Issues)(Average Score) Major Investment Areas: Industries: food processing, beverages, clothing and textiles, light manufacturing, salt, cement Exports - commodities: livestock, sorghum, textiles, food, small manufactures Imports - commodities: machinery, petroleum products, food, manufactured goods Investment Restrictions: The Foreign Financed Special Investments (FFSI) Proclamation specifically limits foreign investment in financial services, domestic wholesale trade, domestic retail trade, and commission agencies, but permits investment in other sectors. Overall, investors in Eritrea face risks including lack of transparency in the regulatory process, limits on possession and exchange of foreign currency, lack of thoroughgoing dispute settlement mechanisms, difficulty in obtaining licenses, potential expropriation of private assets, and infrastructure challenges such as high fuel prices and inconsistent provision of electricity and water. The nation’s most successful economic sector is mining. The GSE has courted diaspora -

The Foreign Military Presence in the Horn of Africa Region

SIPRI Background Paper April 2019 THE FOREIGN MILITARY SUMMARY w The Horn of Africa is PRESENCE IN THE HORN OF undergoing far-reaching changes in its external security AFRICA REGION environment. A wide variety of international security actors— from Europe, the United States, neil melvin the Middle East, the Gulf, and Asia—are currently operating I. Introduction in the region. As a result, the Horn of Africa has experienced The Horn of Africa region has experienced a substantial increase in the a proliferation of foreign number and size of foreign military deployments since 2001, especially in the military bases and a build-up of 1 past decade (see annexes 1 and 2 for an overview). A wide range of regional naval forces. The external and international security actors are currently operating in the Horn and the militarization of the Horn poses foreign military installations include land-based facilities (e.g. bases, ports, major questions for the future airstrips, training camps, semi-permanent facilities and logistics hubs) and security and stability of the naval forces on permanent or regular deployment.2 The most visible aspect region. of this presence is the proliferation of military facilities in littoral areas along This SIPRI Background the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa.3 However, there has also been a build-up Paper is the first of three papers of naval forces, notably around the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, at the entrance to devoted to the new external the Red Sea and in the Gulf of Aden. security politics of the Horn of This SIPRI Background Paper maps the foreign military presence in the Africa. -

Eritrea National Service, Exit and Entry – Jan. 2020

COUNTRY REPORT January 2020 COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) Eritrea National service, exit and entry newtodenmark.dk © 2020 The Danish Immigration Service The Danish Immigration Service Ryesgade 53 2100 Copenhagen Denmark Phone: +45 35 36 66 00 newtodenmark.dk January 2020 All rights reserved to the Danish Immigration Service. The publication can be downloaded for free at newtodenmark.dk The Danish Immigration Service’s publications can be quoted with clear source reference. ERITREA – NATIONAL SERVICE, EXIT, ENTRY Contents Disclaimer ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................. 4 Executive summary .......................................................................................................................... 5 Map of Eritrea .................................................................................................................................. 6 1. Introduction and methodology ................................................................................................ 7 2. Background: recent developments in Eritrean politics ................................................................. 12 2.1 Brief overview of the general situation in Eritrea, including human rights .......................................... 15 3. National Service ........................................................................................................................ -

ABSTRACT YEMANE DESTA. Designing

ABSTRACT YEMANE DESTA. Designing Anti-Corruption Strategies for Developing Countries: A Country Study of Eritrea. (Under the direction of James H. Svara) The purpose of this research is to identify the anti-corruption strategies available for fighting corruption in developing countries and assess their relevance to the newly independent country of Eritrea by canvassing the opinions of Eritrean public officials. The anti-corruption strategies considered in the study are divided into four broad categories: Economic/Market Reforms, Administrative/Bureaucratic Reforms, Accountability/Transparency Enhancing Reforms, and Political Accountability Enhancing Reforms. Data are collected through the administration of questionnaires to a sample of 62 Eritrean public officials from 13 ministries of the Eritrean Government to assess their views regarding the extent, causes and remedies of corruption in Eritrea. The survey evidence indicates that the overwhelming majority (90 percent) of the respondents believe the issue of corruption in the context of Eritrean public administration is important. Moreover, an overwhelming majority (95 percent) of the respondents think that high emphasis should be given to preventing/fighting corruption at present. For the years 2000 and 2003 the majority (64.5 percent) of the respondents believe that corruption in Eritrea ranges between none to minimal while 35.5 percent think corruption in Eritrea ranges between moderate to prevalent. Two important differences are observed between respondents who perceive lower rates of corruption and those who perceive higher rates of corruption. The research indicates that respondents who have not received foreign education are more likely to perceive higher levels of corruption (38 percent) than respondents who received foreign education (18 percent). -

Second Stage of the Proceedings Between Eritrea and Yemen (Maritime Delimitation)

REPORTS OF INTERNATIONAL ARBITRAL AWARDS RECUEIL DES SENTENCES ARBITRALES Second stage of the proceedings between Eritrea and Yemen (Maritime Delimitation) 17 December 1999 VOLUME XXII pp. 335-410 NATIONS UNIES - UNITED NATIONS Copyright (c) 2006 Part IV Award of the Arbitral Tribunal in the second stage of the proceedings between Eritrea and Yemen (Maritime Delimitation) Decision of 17 December 1999 Sentence du Tribunal arbitral rendue au terme de la seconde étape de la procédure entre l'Erythrée et la République du Yémen (Délimitation maritime) Décision du 17 décembre 1999 334 ERITREA / YEMEN AWARD OF THE ARBITRAL TRIBUNAL IN THE SECOND STAGE OF THE PROCEEDINGS BETWEEN ERITREA AND YEMEN (MARI- TIME DELIMITATION), 17 DECEMBER 1999 SENTENCE DU TRIBUNAL ARBITRAL RENDUE AU TERME DE LA SECONDE ÉTAPE DE LA PROCÉDURE ENTRE L'ERYTHRÉE ET LA RÉPUBLIQUE DU YÉMEN (DÉLIMITATION MARITIME), 17 DÉCEMBRE 1999 Median line and historic median line — Methods of measurement — Principle of equidistance — Baselines: high water-line, low water-line, median line - "normal baseline", "straight baseline" — Geodeic line. — Presence of mid sea islands — Principle of proportionality as a test of equi- tableness and not a method of delimitation — Requirement of an equitable solution. Non-geographical relevant circumstances: fishing, security, principle of non-encroachment — Relevance of fishing in acceptance or rejecting the argument as to the line of delimitation: location of fishing areas, economic dependency on fishing, effect of fishing practices on the lines of delimitation — "catastrophic" and "long usage" tests — "artisanal fishing", "industrial fish- ing", and associated rights. The drawing of the initial boundary line does not depend on the existence and the protec- tion of the traditional fishing regime. -

Middle Eastern Base Race in North-Eastern Africa

STUDIES IN AFRICAN SECURITY Turkey, United Arab Emirates and other Middle Eastern States Middle Eastern Base Race in North-Eastern Africa This text is a part of the FOI report Foreign military bases and installations in Africa. Twelve state actors are included in the report: China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Russia, Spain, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, and United States. Middle Eastern states are increasing their military region. Turkey’s political interests are in line with those presence in Africa. Turkey and the United Arab of Qatar on the question of political Islam and the MB, Emirates (UAE), two influential Sunni powers with but clash with the agenda of the UAE and Saudi Arabia. contrary views on regional order and political Islam, The conflict among the Sunni powers has intensified since are expanding their foothold in north-eastern Africa. the Arab Spring in 2010, in particular since the UAE-led Turkey has opened a military training facility in blockade against Qatar in 2017. Eastern Africa has thus Somalia and may build a naval dock for military use become an arena for the rivalry between regional powers in Sudan. The UAE has established bases in Eritrea of the Middle East. and Libya, and is currently constructing a base in President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his AK party have Somaliland. However, Turkey and UAE are not the strengthened the Sunni Muslim identity of the Turkish only Middle Eastern countries with a military presence state, while de facto approving a neo-Ottoman foreign in Africa. Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Israel, and Iran, also policy that implies a growing focus on the Middle East seem to have military activities on the Horn of Africa. -

Causes, Consequences and Remedies of Juvenile Delinquency in the Context of Sub-Saharan Africa: a Study of 70 Juvenile Delinquents in the Eritrean Capital, Asmara

International Journal of Public Administration and Policy Research Vol. 5(2), pp. 91-110, April, 2020. © www.premierpublishers.org, ISSN: 0274-6999 Research Article Causes, Consequences and Remedies of Juvenile Delinquency in the Context of Sub-Saharan Africa: A Study of 70 Juvenile Delinquents in the Eritrean Capital, Asmara Dr. Yemane Desta (PhD) Department of Public Administration, College of Business and Social Sciences, University of Asmara, P.O.BOX 1220, Asmara, Eritrea Email: [email protected] Telephone Number: 291-7645753 This research work was designed to examine nature of juvenile offences committed by juveniles, causes of juvenile delinquency, consequences of juvenile delinquency and remedies for juvenile delinquency in the context of Sub-Saharan Africa with specific reference to Eritrea. Left unchecked, juvenile delinquents on the streets engage in petty theft, take alcohol or drugs, rape women, rob people at night involve themselves in criminal gangs and threaten the public at night. To shed light on the problem of juvenile delinquency in the Sub- Saharan region data was collected through primary and secondary sources. A sample size of 70 juvenile delinquents was selected from among 112 juvenile delinquents in remand at the Asmara Juvenile Rehabilitation Center in the Eritrean capital. The study was carried out through coded self-administered questionnaires administered to a sample of 70 juvenile delinquents. The survey evidence indicates that the majority of the juvenile respondents come either from families constructed by unmarried couples or separated or divorced parents where largely the father is missing in the home or dead. The findings also indicate that children born out of wedlock, families led by single mothers, lack of fatherly role models, poor parental-child relationships and negative peer group influence as dominant causes of juvenile infractions. -

Corruption Perceptions Index 2019

CORRUPTION PERCEPTIONS INDEX 2019 Transparency International is a global movement with one vision: a world in which government, business, civil society and the daily lives of people are free of corruption. With more than 100 chapters worldwide and an international secretariat in Berlin, we are leading the fight against corruption to turn this vision into reality. #cpi2019 www.transparency.org/cpi Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. All information was believed to be correct as of January 2020. Nevertheless, Transparency International cannot accept responsibility for the consequences of its use for other purposes or in other contexts. ISBN: 978-3-96076-134-1 2020 Transparency International. Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under CC BY-ND 4.0 DE. Quotation permitted. Please contact Transparency International – [email protected] – regarding derivatives requests. CORRUPTION PERCEPTIONS INDEX 2019 2-3 14-15 22-23 Map and results Asia Pacific Western Europe & Indonesia European Union 4-5 Papua New Guinea Malta Executive summary Estonia Recommendations 16-17 Eastern Europe & 24-25 Central Asia Trouble at the top 6-8 Armenia Global highlights TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE Kosovo 26 Methodology 9-11 18-19 Political integrity Middle East & North 27-29 Transparency in Africa Endnotes campaign finance Tunisia Political decision-making Saudi Arabia 12-13 20-21 Americas Sub-Saharan Africa United States Angola Brazil Ghana TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL 180 COUNTRIES. 180 SCORES. -

Causes of Corruption from Entrepreneurs' Perceptions

R M B www.irmbrjournal.com December 2014 R International Review of Management and Business Research Vol. 3 Issue.4 I Causes of Corruption from Entrepreneurs’ Perceptions: Theoretical and Practical Implications. MUSSIE T. TESSEMA Ph.D., Business Administration Dept, Winona State University, MN. Som323F. Email: [email protected] Tel. 507-457-2571 MENGSTEAB TESFAYOHANNES-BERAKI Ph.D., Susquehanna University Email: [email protected] SEBHATLEAB TEWOLDE Ph.D., Department of Accounting, University of Asmara Email: [email protected] KIFLEYESUS ANDEMARIAM Ph.D., Department of Management, University of Asmara Email: [email protected] Abstract This study assesses the extent to which ten selected factors affect corruption in Least Developed Countries (LDCs). The study uses Eritrea as a case study and delves into the causes and challenges of corruption in LDCs. The findings of the study support several previously conducted studies in that each factor examined had a moderate to high positive correlation with corruption, where r ranged between .47 and .59. In addition, the ten variables together explain about 73 percent change in perceived corruption (R2= .73). The study acknowledges that corruption is multifaceted and complicated, involving economic, political, and social-cultural factors and has no „quick fix‟ and thus needs proper planning, determination, resilience, and above all, political will. Implications of these findings and future research directions are discussed. Key Words: Governance, Accountability, Corruption, LDCs, Eritrea, Entrepreneurs, Business Eethics. Introduction One of the main tasks assumed by governments world-wide is promoting economic and social development. If these tasks are to be accomplished successfully, a number of pre-conditions must exist. -

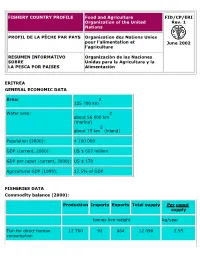

Eritrea General Economic Data

FISHERY COUNTRY PROFILE Food and Agriculture FID/CP/ERI Organization of the United Rev. 1 Nations PROFIL DE LA PÊCHE PAR PAYS Organisation des Nations Unies pour l'alimentation et June 2002 l'agriculture RESUMEN INFORMATIVO Organización de las Naciones SOBRE Unidas para la Agricultura y la LA PESCA POR PAISES Alimentación ERITREA GENERAL ECONOMIC DATA Area: 2 125 700 km Water area: 2 about 56 000 km (marine) 2 about 15 km (inland) Population (2000): 4 100 000 GDP (current, 2000): US $ 607 million GDP per caput (current, 2000): US $ 170 Agricultural GDP (1999): 17.5% of GDP FISHERIES DATA Commodity balance (2000): Production Imports Exports Total supply Per caput supply tonnes live-weight kg/year Fish for direct human 12 700 92 664 12 098 2.95 consumption Fish for animal feed and 1 700 - - 1 700 other purposes Estimated employment (2002): (i) Primary sector: 3 500 (ii) Secondary sector: 10 000 (part time, estimated) Gross value of fisheries output (at ex-vessel prices) 2000: US $5 500 000 (estimated) Trade (2000), estimated: Value of imports US $ 0.1 million Value of exports US $ 2.1 million THE STRUCTURE AND CHARACTERISTICS OF THE INDUSTRY Marine fisheries 2 Located at the widest part of the Red Sea, Eritrea has an EEZ of 121 000 km . Its mainland coastline is about 1 900 km from the Sudan border to the Jibouti border. Eritrea has a 2 continental shelf of 56 000 km with a plateau containing 360 islands that define the Dahlak Archipelago. The latter add another 1 300 km of coastline. -

ETHIOPIA, RED SEA, and NILE RIVER Previous Science Focus! Articles Have Discussed a Particular Phenomenon That Is Visible in Seawifs Data and Imagery

SCIENCE FOCUS: ETHIOPIA, RED SEA, AND NILE RIVER Previous Science Focus! articles have discussed a particular phenomenon that is visible in SeaWiFS data and imagery. In this case, however, SeaWiFS has provided superb views of a distant region of the world that has many unique geological and physical features. Furthermore, this region of Africa has both archaeological and anthropological significance. Hominid fossils found here indicate that this region may be the origin of humanity's presence on Earth, and the Nile River valley and delta are the home of numerous archaeological sites from the time of the Pharaohs. The SeaWiFS image below is centered on Ethiopia. The sites that are labeled will be discussed on the following pages. The image without labels appears on page 4. Starting at the top right, the capital city of Sudan, Khartoum, is located at the convergence of the Blue Nile and the White Nile. Although the Blue Nile is much shorter than the White Nile, it contributes about 80% of the flow of the river. Moving west, the Dahlak Archipelago is seen off the Red Sea coast of Eritrea. Because of their isolation, the numerous coral reefs of the Dahlak Archipelago are some of the most pristine remaining in the world. Portions of the Dahlak Archipelago are in the Dahlak Marine National Park. Directly south of the Dahlak Archipelago, in the inhospitable desert region of the Afar Triangle and the Danakil Depression, is the active shield volcano Erta Ale. The summit crater of Erta Ale holds an active lava lake. South of Erta Ale, the terminal delta of the Awash River can be seen. -

The Anatomy of the Resource Curse: Predatory Investment in Africa’S Extractive Industries

ACSS SPECIAL REPORT A PUBLICATION OF THE AFRICA CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES The Anatomy of the Resource Curse: Predatory Investment in Africa’s Extractive Industries J.R. Mailey May 2015 The Africa Center for Strategic Studies The Africa Center is an academic institution established by the U.S. Department of Defense and funded by Congress for the study of security issues relating to Africa. It serves as a forum for bilateral and multilateral research, communication, and the exchange of ideas. The Anatomy of the Resource Curse: Predatory Investment in Africa’s Extractive Industries ACSS Special Report No. 3 J.R. Mailey May 2015 Africa Center for Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Portions of this work may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line is included. The Africa Center would appreciate a courtesy copy of reprints or reviews. First printing, May 2015. For additional publications of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, visit the Center’s Web site at http://africacenter.org. Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................1 Part 1: Africa’s Natural Resource Challenge ...........................................5 Natural Resource Wealth and