Adescriptive Analysis of Temporal and Spatial Patterns Ofvariability in Puget Sound Oceanographic Properties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identifying Potential Juvenile Steelhead Predators in the Marine Waters of the Salish Sea

Early Marine Survival Project Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife Identifying Potential Juvenile Steelhead Predators In the Marine Waters of the Salish Sea Scott F. Pearson, Steven J. Jeffries, and Monique M. Lance Wildlife Science Division Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Olympia Austen Thomas Zoology Department University of British Columbia Robin Brown Early Marine Survival Project Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife Cover photo: Robin Brown, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Seals, sea lions, gulls and cormorants on the tip of the South Jetty at the mouth of the Columbia River. We selected this photograph to emphasize that bird and mammal fish predators can be found together in space and time and often forage on the same resources. Suggested citation: Pearson, S.F., S.J. Jeffries, M.M. Lance and A.C. Thomas. 2015. Identifying potential juvenile steelhead predators in the marine waters of the Salish Sea. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Wildlife Science Division, Olympia. Identifying potential steelhead predators 1 INTRODUCTION Puget Sound wild steelhead were listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 2007 and their populations are now less than 10% of their historic size (Federal Register Notice: 72 FR 26722). A significant decline in abundance has occurred since the mid-1980s (Federal Register Notice: 72 FR 26722), and data suggest that juvenile steelhead mortality occurring in the Salish Sea (waters of Puget Sound, the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the San Juan Islands as well as the water surrounding British Columbia’s Gulf Islands and the Strait of Georgia) marine environment constitutes a major, if not the predominant, factor in that decline (Melnychuk et al. -

MIMOC: a Global Monthly Isopycnal Upper-Ocean Climatology with Mixed Layers*

1 * 1 MIMOC: A Global Monthly Isopycnal Upper-Ocean Climatology with Mixed Layers 2 3 Sunke Schmidtko1,2, Gregory C. Johnson1, and John M. Lyman1,3 4 5 1National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Pacific Marine Environmental 6 Laboratory, Seattle, Washington 7 2University of East Anglia, School of Environmental Sciences, Norwich, United 8 Kingdom 9 3Joint Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 10 Honolulu, Hawaii 11 12 Accepted for publication in 13 Journal of Geophysical Research - Oceans. 14 Copyright 2013 American Geophysical Union. Further reproduction or electronic 15 distribution is not permitted. 16 17 8 February 2013 18 19 ______________________________________ 20 *Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory Contribution Number 3805 21 22 Corresponding Author: Sunke Schmidtko, School of Environmental Sciences, University 23 of East Anglia, Norwich, NR4 7TJ, UK. Email: [email protected] 2 24 Abstract 25 26 A Monthly, Isopycnal/Mixed-layer Ocean Climatology (MIMOC), global from 0–1950 27 dbar, is compared with other monthly ocean climatologies. All available quality- 28 controlled profiles of temperature (T) and salinity (S) versus pressure (P) collected by 29 conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) instruments from the Argo Program, Ice-Tethered 30 Profilers, and archived in the World Ocean Database are used. MIMOC provides maps 31 of mixed layer properties (conservative temperature, Θ, Absolute Salinity, SA, and 32 maximum P) as well as maps of interior ocean properties (Θ, SA, and P) to 1950 dbar on 33 isopycnal surfaces. A third product merges the two onto a pressure grid spanning the 34 upper 1950 dbar, adding more familiar potential temperature (θ) and practical salinity (S) 35 maps. -

Geology of Blaine-Birch Bay Area Whatcom County, WA Wings Over

Geology of Blaine-Birch Bay Area Blaine Middle Whatcom County, WA School / PAC l, ul G ant, G rmor Wings Over Water 2020 C o n Nest s ero Birch Bay Field Trip Eagles! H March 21, 2020 Eagle "Trees" Beach Erosion Dakota Creek Eagle Nest , ics l at w G rr rfo la cial E te Ab a u ant W Eagle Nest n d California Heron Rookery Creek Wave Cut Terraces Kingfisher G Nests Roger's Slough, Log Jam Birch Bay Eagle Nest G Beach Erosion Sea Links Ponds Periglacial G Field Trip Stops G Features Birch Bay Route Birch Bay Berm Ice Thickness, 2,200 M G Surficial Geology Alluvium Beach deposits Owl Nest Glacial outwash, Fraser-age in Barn k Glaciomarine drift, Fraser-age e e Marine glacial outwash, Fraser-age r Heron Center ll C re Peat deposits G Ter Artificial fill Terrell Marsh Water T G err Trailhead ell M a r k sh Terrell Cr ee 0 0.25 0.5 1 1.5 2 ± Miles 2200 M Blaine Middle Glacial outwash, School / PAC Geology of Blaine-Birch Bay Area marine, Everson ll, G Gu Glaciomarine Interstade Whatcom County, WA morant, C or t s drift, Everson ron Nes Wings Over Water 2020 Semiahmoo He Interstade Resort G Blaine Semiahmoo Field Trip March 21, 2020 Eagle "Trees" Semiahmoo Park G Glaciomarine drift, Everson Beach Erosion Interstade Dakota Creek Eagle Nest Glac ial Abun E da rra s, Blaine nt ti c l W ow Eagle Nest a terf California Creek Heron Glacial outwash, Rookery Glaciomarine drift, G Field Trip Stops marine, Everson Everson Interstade Semiahmoo Route Interstade Ice Thickness, 2,200 M Kingfisher Surficial GNeeoslotsgy Wave Cut Alluvium Glacial Terraces Beach deposits outwash, Roger's Glacial outwash, Fraser-age Slough, SuGmlaacsio mSataridnee drift, Fraser-age Log Jam Marine glacial outwash, Fraser-age Peat deposits Beach Eagle Nest Artificial fill deposits Water Beach Erosion 0 0.25 0.5 1 1.5 2 Miles ± Chronology of Puget Sound Glacial Events Sources: Vashon Glaciation Animation; Ralph Haugerud; Milepost Thirty-One, Washington State Dept. -

Development of a Hydrodynamic Model of Puget Sound and Northwest Straits

PNNL-17161 Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 Development of a Hydrodynamic Model of Puget Sound and Northwest Straits Z Yang TP Khangaonkar December 2007 DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor Battelle Memorial Institute, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or Battelle Memorial Institute. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. PACIFIC NORTHWEST NATIONAL LABORATORY operated by BATTELLE for the UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 Printed in the United States of America Available to DOE and DOE contractors from the Office of Scientific and Technical Information, P.O. Box 62, Oak Ridge, TN 37831-0062; ph: (865) 576-8401 fax: (865) 576-5728 email: [email protected] Available to the public from the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, 5285 Port Royal Rd., Springfield, VA 22161 ph: (800) 553-6847 fax: (703) 605-6900 email: [email protected] online ordering: http://www.ntis.gov/ordering.htm This document was printed on recycled paper. -

Trophic Diversity of Plankton in the Epipelagic and Mesopelagic Layers of the Tropical and Equatorial Atlantic Determined with Stable Isotopes

diversity Article Trophic Diversity of Plankton in the Epipelagic and Mesopelagic Layers of the Tropical and Equatorial Atlantic Determined with Stable Isotopes Antonio Bode 1,* ID and Santiago Hernández-León 2 1 Instituto Español de Oceanografía, Centro Oceanográfico de A Coruña, Apdo 130, 15080 A Coruña, Spain 2 Instituto de Oceanografía y Cambio Global (IOCAG), Universidad de las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Campus de Taliarte, Telde, Gran Canaria, 35214 Islas Canarias, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-981205362 Received: 30 April 2018; Accepted: 12 June 2018; Published: 13 June 2018 Abstract: Plankton living in the deep ocean either migrate to the surface to feed or feed in situ on other organisms and detritus. Planktonic communities in the upper 800 m of the tropical and equatorial Atlantic were studied using the natural abundance of stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes to identify their food sources and trophic diversity. Seston and zooplankton (>200 µm) samples were collected with Niskin bottles and MOCNESS nets, respectively, in the epipelagic (0–200 m), upper mesopelagic (200–500 m), and lower mesopelagic layers (500–800 m) at 11 stations. Food sources for plankton in the productive zone influenced by the NW African upwelling and the Canary Current were different from those in the oligotrophic tropical and equatorial zones. In the latter, zooplankton collected during the night in the mesopelagic layers was enriched in heavy nitrogen isotopes relative to day samples, supporting the active migration of organisms from deep layers. Isotopic niches showed also zonal differences in size (largest in the north), mean trophic diversity (largest in the tropical zone), food sources, and the number of trophic levels (largest in the equatorial zone). -

Water Quality

Section 7: Water Quality SECTION 7 How is Puget Sound’s Water Quality Changing? Puget Sound is projected to experience a continued increase in sea surface temperatures, and continued declines in pH and dissolved oxygen concentrations. These changes, which could affect marine ecosystems and the shellfish industry, will be affected by variations in coastal upwelling and circulation within Puget Sound. While it is currently not known how climate change will affect circulation and upwelling in the region, these processes will continue to fluctuate in response to natural climate variability. Impacts on marine ecosystems and shellfish farming generally point to increasing stress for fish and shellfish populations. Efforts to address Puget Sound’s water quality are increasing, particularly in the areas of ocean acidification monitoring and implementation of risk reduction practices in the shellfish industry. Climate Drivers of Change DRIVERS Wind patterns, natural climate variability, and projected changes in temperature and precipitation can all affect water quality in Puget Sound.A Observations show a clear warming trend, and all scenarios project continued warming during this century. Most scenarios project that this warming will be outside of the range of historical variations by mid-century (see Section 2).1,2 Warming. The salinity of Puget Sound’s waters is tightly linked to freshwater inflows from streams. Increasing air temperatures will result in more precipitation falling as rain instead of snow, leading to more freshwater inflows into Puget Sound during winter months, and decreased freshwater inflows during summer. In addition, increasing air temperatures are expected to drive a continued increase in water temperatures, increasing the likelihood of harmful algal blooms (see Section 3). -

Impact of the Pycnocline Layer on Bacterioplankton

MARINE ECOLOGY - PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 38: 295403, 1987 Published July 13 Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. l Impact of the pycnocline layer on bacterioplankton: diel and spatial variations in microbial parameters in the stratified water column of the Gulf of Trieste (Northern Adriatic Sea) Gerhard J. ~erndl'& Vlado ~alaCiC~ ' Institute for Zoology. University of Vienna. Althanstr. 14, A-1090 Vienna, Austria Marine Biology Station Piran, Cesta JLA 65, YU-66330 Piran. Yugoslavia ABSTRACT: Die1 variations in bacterial density, frequency of bvidlng cells (FDC) and bssolved organic carbon (DOC) in the stratified water column of the Gulf of Trieste were investigated at various depths. In the surface layers morning and afternoon DOC peaks (up to 10 mg I-') were observed in 3 out of 4 diel cycles. Bacterial abundance remained fairly constant over the diel cycles; however, bacterial activity as measured by FDC showed pronounced peaks in late afternoon and dawn coinciding with the DOC maximum concentrations. The pycnocline layer exhibited DOC concentrations similar to those of the overlying waters. The frequency of dividing cells (FDC), however, remained high throughout the entire diel cycle. The observed pronounced diel variations in bacterial production were therefore largely restricted to the layers well above the pycnocline; bacterial production contributed less than 20 % to the overall diel production (500 to 1000 pg C 1-' d-') in the uppermost 5 m water body. Highest diel production was found in the pycnocline layer at the end of the phytoplankton bloom (June and July) probably reflecting the formation of nutrient-enriched microzones around decaying phytoplankton cells due to reduced sinking velocities in the pycnocline layer. -

Dispersion in the Open Ocean Seasonal Pycnocline at Scales of 1–10Km and 1–6 Days

FEBRUARY 2020 S U N D E R M E Y E R E T A L . 415 Dispersion in the Open Ocean Seasonal Pycnocline at Scales of 1–10km and 1–6 days a MILES A. SUNDERMEYER AND DANIEL A. BIRCH University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, North Dartmouth, Massachusetts JAMES R. LEDWELL Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, Massachusetts b MURRAY D. LEVINE, STEPHEN D. PIERCE, AND BRANDY T. KUEBEL CERVANTES Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon (Manuscript received 23 January 2019, in final form 14 November 2019) ABSTRACT Results are presented from two dye release experiments conducted in the seasonal thermocline of the 2 2 Sargasso Sea, one in a region of low horizontal strain rate (;10 6 s 1), the second in a region of intermediate 2 2 horizontal strain rate (;10 5 s 1). Both experiments lasted ;6 days, covering spatial scales of 1–10 and 1–50 km for the low and intermediate strain rate regimes, respectively. Diapycnal diffusivities estimated from 26 2 21 2 21 the two experiments were kz 5 (2–5) 3 10 m s , while isopycnal diffusivities were kH 5 (0.2–3) m s , with the range in kH being less a reflection of site-to-site variability, and more due to uncertainties in the background strain rate acting on the patch combined with uncertain time dependence. The Site I (low strain) experiment exhibited minimal stretching, elongating to approximately 10 km over 6 days while maintaining a width of ;5 km, and with a notable vertical tilt in the meridional direction. By contrast, the Site II (inter- mediate strain) experiment exhibited significant stretching, elongating to more than 50 km in length and advecting more than 150 km while still maintaining a width of order 3–5 km. -

The Fate of Onsite Septic System Nitrogen Discharges in Groundwater of the Hood Canal Basin

The Fate of Onsite Septic System Nitrogen Discharges in Groundwater of the Hood Canal Basin Julie Horowitz, Bryan Atieh, Garrett Leque, Mark Benjamin, Michael Brett Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Washington The Story… ¾Eutrophication and low dissolved oxygen ¾Hood Canal ¾Onsite Septic Systems (OSS) as a potential source of nitrogen loading ¾Denitrification – the key variable in determining the nitrogen load ¾Measuring denitrification in the Hood Canal basin ¾Substantial spatial and temporal variability in denitrification U.S. Coastal ‘Dead Zones’ Associated with Human Activity Date of Hypoxic event 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000 Source: America’s Oceans: Charting a Course for the Sea Change. Pew Ocean Commission report June, 2003 Hood Canal, Washington Eutrophication in Hood Canal Hood Canal is an estuary where OSS N loading may exacerbate eutrophication. HCDOP HCDOP HCDOP , pet waste, lawns Newton, UW-APL Loading from OSS to Hood Canal Denitrification rates X Census data Travel Distance Household Groundwater Trash output Traffic studies Septic inputs nitrogen velocity Seasonal Per capita Septic Nitrogen X X Population water use nitrogen - removal effluent Nitrogen load to Hood Canal Nitrogen Fate and Transport Drainfield Septic Tank + Organic N Æ NH4 2 N Drainfield and Vadose Zone + - NH4 Æ NO3 N Denitrification O - NO3 Æ N2 3 Groundwater Flow Denitrification ¾Denitrification is the primary N removal process. + - - ¾Organic N NH4 NO2 /NO3 N2 ¾Requirements: 1) Denitrifying microbial population 2) Anoxic conditions -

Habs in UPWELLING SYSTEMS

GEOHAB CORE RESEARCH PROJECT: HABs IN UPWELLING SYSTEMS 1 GEOHAB GLOBAL ECOLOGY AND OCEANOGRAPHY OF HARMFUL ALGAL BLOOMS GEOHAB CORE RESEARCH PROJECT: HABS IN UPWELLING SYSTEMS AN INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMME SPONSORED BY THE SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE ON OCEANIC RESEARCH (SCOR) AND THE INTERGOVERNMENTAL OCEANOGRAPHIC COMMISSION (IOC) OF UNESCO EDITED BY: G. PITCHER, T. MOITA, V. TRAINER, R. KUDELA, P. FIGUEIRAS, T. PROBYN BASED ON CONTRIBUTIONS BY PARTICIPANTS OF THE GEOHAB OPEN SCIENCE MEETING ON HABS IN UPWELLING SYSTEMS AND THE GEOHAB SCIENTIFIC STEERING COMMITTEE February 2005 3 This report may be cited as: GEOHAB 2005. Global Ecology and Oceanography of Harmful Algal Blooms, GEOHAB Core Research Project: HABs in Upwelling Systems. G. Pitcher, T. Moita, V. Trainer, R. Kudela, P. Figueiras, T. Probyn (Eds.) IOC and SCOR, Paris and Baltimore. 82 pp. This document is GEOHAB Report #3. Copies may be obtained from: Edward R. Urban, Jr. Henrik Enevoldsen Executive Director, SCOR Programme Co-ordinator Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences IOC Science and Communication Centre on The Johns Hopkins University Harmful Algae Baltimore, MD 21218 U.S.A. Botanical Institute, University of Copenhagen Tel: +1-410-516-4070 Øster Farimagsgade 2D Fax: +1-410-516-4019 DK-1353 Copenhagen K, Denmark E-mail: [email protected] Tel: +45 33 13 44 46 Fax: +45 33 13 44 47 E-mail: [email protected] This report is also available on the web at: http://www.jhu.edu/scor/ http://ioc.unesco.org/hab ISSN 1538-182X Cover photos courtesy of: Vera Trainer Teresa Moita Grant Pitcher Copyright © 2005 IOC and SCOR. -

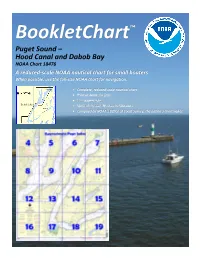

Hood Canal and Dabob Bay NOAA Chart 18476 a Reduced-Scale NOAA Nautical Chart for Small Boaters

BookletChart™ Puget Sound – Hood Canal and Dabob Bay NOAA Chart 18476 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Included Area Published by the mooring buoys, and floats are on both sides of the canal. There are relatively few public floats or piers, and the only commercial activities National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration are logging and some oystering. National Ocean Service Thorndyke Bay is a small bight on the W side of Hood Canal about 4 Office of Coast Survey miles S of Squamish Harbor. An explosives anchorage is S of the bay. (See 110.1 and 110.230, chapter 2, for limits and regulations.) www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov Bangor Wharf on the E side of the canal, 3.5 miles S of Thorndyke Bay, is 888-990-NOAA the property of the Bangor U.S. Naval Submarine Base. A naval restricted area surrounds the wharf and other naval docking facilities What are Nautical Charts? along the E side of Hood Canal. Keyport Naval Undersea Warfare Engineering Station, 0.9 mile SSW of Bangor Wharf, is also within the Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show restricted area. (See 334.1220, chapter 2, for limits and regulations.) water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much Naval security zones are adjacent to the Naval Submarine Base. (See more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and §165.1302 and §165.1311, chapter 2, for limits and regulations.) efficient navigation. Chart carriage is mandatory on the commercial A naval operating area is in the S part of Hood Canal. -

Eutrophication in the US and Elsewhere: NOAA’S National Estuarine Eutrophication Assessment

Eutrophication in the US and Elsewhere: NOAA’s National Estuarine Eutrophication Assessment S.B. Bricker and G. Lauenstein National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science Center for Coastal Monitoring and Assessment Silver Spring, MD, USA 8th National Monitoring Conference Water: One Resource – Shared Effort – Common Future Portland, Oregon April 30-May 4, 2012 http://www.eutro.org http://www.eutro.us National and International Partners Picture yourself here?! Global Context and Guiding Legislation for Nutrient Issues US Clean Water Act of 1972, US Harmful Algal Bloom and Hypoxia Research and Control Act of 1998 EU Water Framework Directive 2000, older generation directives: Urban WasteWater Treatment Directive and Nitrates Directive, Marine Strategy Framework Directive 2008 PRC Environmental Protection Diaz, R.J. and R. Rosenberg. 2008. Spreading dead zones and Law 1989, Law on Prevention and consequences for marine ecosystems. Science 321:926-928 Control of Water Pollution 1996, Eutrophication is a significant problem Marine Environmental Protection worldwide (US, EU, China, Japan, Law of 2000 Australia and elsewhere) ASSETS Eutrophication Assessment Components 科学问题 – 评估方法和成分 SPARROW Pressure State Response SPARROW From: Bricker et al. In press. Coastal Bays in Context, in Shifting Sands http://www.eutro.us http://www.eutro.org/register What does eutrophication look like? Where is it? Caloosahatchee Bay, FL Potomac River, MD Corsica River, MD Florida Bay, FL What does eutrophication look like? Where is it? Hood Canal, WA Washington State