Impact of Salt Retention on True Batch Reverse Osmosis Energy Consumption: Experiments and Model Validation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Treatment and Reverse Osmosis Systems

Pure Aqua, Inc.® Water© 2012 TreatmentPure Aqua ,and Inc. ReverseAll Right sOsmosis Reserve dSystems. Worldwide Experience Superior Technology About the Company Pure Aqua is a company with a strong philosophy and drive to develop and apply solutions to the world’s water treatment challenges. We believe that both our technology and experience will help resolve the growing shortage of clean water worldwide. Capabilities and Expertise As an ISO 9001:2008 certified company with over a decade of experience, Pure Aqua has secured its position as a leading manufacturer of reverse osmosis systems worldwide. Goals and Motivations Our goal is to provide environmentally sustainable systems and equipment that produce high quality water. We provide packaged systems and technical support for water treatment plants, industrial wastewater reuse, and brackish and seawater reverse osmosis plants. Having strong working relationships with Thus, we ensure our technological our suppliers gives us the capability to contribution to water preservation by provide cost effective and competitive supplying the means and making it highly water and wastewater treatment systems accessible. for a wide range of applications. Seawater Reverse Osmosis Systems System Overview Designed to convert seawater to potable water, desalination systems use high quality reverse osmosis seawater membranes. The process separates dissolved salts by only allowing pure water to pass through the membrane fabric. System Capacities Pure Aqua desalination systems are designed to provide high -

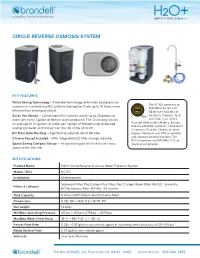

Circle Reverse Osmosis System

CIRCLE REVERSE OSMOSIS SYSTEM KEY FEATURES Water Saving Technology – Patented technology eliminates backpressure The RC100 conforms to common in conventional RO systems making the Circle up to 10 times more NSF/ANSI 42, 53 and efficient than existing products. 58 for the reduction of Saves You Money – Conventional RO systems waste up to 24 gallons of Aesthetic Chlorine, Taste water per every 1 gallon of filtered water produced. The Circle only wastes and Odor, Cyst, VOCs, an average of 2.1 gallons of water per 1 gallon of filtered water produced, Fluoride, Pentavalent Arsenic, Barium, Radium 226/228, Cadmium, Hexavalent saving you water and money over the life of the product!. Chromium, Trivalent Chromium, Lead, RO Filter Auto Flushing – Significantly extends life of RO filter. Copper, Selenium and TDS as verified Chrome Faucet Included – With integrated LED filter change indicator. and substantiated by test data. The RC100 conforms to NSF/ANSI 372 for Space Saving Compact Design – Integrated rapid refill tank means more low lead compliance. space under the sink. SPECIFICATIONS Product Name H2O+ Circle Reverse Osmosis Water Filtration System Model / SKU RC100 Installation Undercounter Sediment Filter, Pre-Carbon Plus Filter, Post Carbon Block Filter (RF-20): 6 months Filters & Lifespan RO Membrane Filter (RF-40): 24 months Tank Capacity 6 Liters (refills fully in less than one hour) Dimensions 9.25” (W) x 16.5” (H) x 13.75” (D) Net weight 14.6 lbs Min/Max Operating Pressure 40 psi – 120 psi (275Kpa – 827Kpa) Min/Max Water Feed Temp 41º F – 95º F (5º C – 35º C) Faucet Flow Rate 0.26 – 0.37 gallons per minute (gpm) at incoming water pressure of 20–100 psi Rated Service Flow 0.07 gallons per minute (gpm) Warranty One Year Warranty PO Box 470085, San Francisco CA, 94147–0085 brondell.com 888-542-3355. -

Refinery Wastewater Management Using Multiple Angle Oil-Water Separators

REFINERY WASTEWATER MANAGEMENT USING MULTIPLE ANGLE OIL-WATER SEPARATORS Kirby S. Mohr, P.E. Mohr Separations Research, Inc. 1278 FM 407 Suite 109 Lewisville, TX 75077 Phone: 918-299-9290 Cell: 918-269-8710 John N. Veenstra, Ph.D., P.E., Oklahoma State University Dee Ann Sanders, Ph.D., P.E. Oklahoma State University A paper presented at the International Petroleum Environment Conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1998 ABSTRACT In this work, an overview of oil-water separation, as used in the petroleum refining industries, is presented along with case studies. Discussions include: impact of solids, legal aspects, and differing types of systems currently in use, along with their advantages and disadvantages. Performance information on separators is presented with an emphasis on new multiple angle coalescing plate technology for refinery wastewater management. Several studies are presented including a large (20,000 US GPM flow rate) system recently installed at a major US refinery. The separator was constructed by converting two existing API separators into four separators, and adding multiple angle coalescing plates to increase throughput and efficiency. A year of operating experience with this system indicates good performance and few problems. Other examples provide information on separators installed in the United States and other countries. Keywords: Oil-water separator, multiple angle, coalescence, refinery, wastewater management, petroleum, coalescing plate technology BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION Oil has been refined for various uses for at least 1000 years. An Arab handbook written by Al-Razi, in approximately 865 A.D., describes distillation of “naft” (naphtha) for use in lamps and thus the beginning of oil refining (Forbes). -

Reverse Osmosis As a Pretreatment of Ion Exchange Equipment at PSE

Copyright Warning & Restrictions The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a, user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use” that user may be liable for copyright infringement, This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. Please Note: The author retains the copyright while the New Jersey Institute of Technology reserves the right to distribute this thesis or dissertation Printing note: If you do not wish to print this page, then select “Pages from: first page # to: last page #” on the print dialog screen The Van Houten library has removed some of the personal information and all signatures from the approval page and biographical sketches of theses and dissertations in order to protect the identity of NJIT graduates and faculty. ABSTRACT REVERSE OSMOSIS AS A PRETREATMENT FOR ION EXCHANGE AT PSE&G'S HUDSON GENERATING STATION by Steven Leon Public Service Electric and Gas Company's Hudson Generating Station has historically had problems providing sufficient high quality water for its two once through, supercritical design boilers. The station requires over 60 million gallons annually to compensate for system losses. -

Selective Salt Recovery from Reverse Osmosis Concentrate Using Inter-Stage Ion Exchange Joshua E

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Civil Engineering ETDs Engineering ETDs 7-3-2012 Selective salt recovery from reverse osmosis concentrate using inter-stage ion exchange Joshua E. Goldman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ce_etds Recommended Citation Goldman, Joshua E.. "Selective salt recovery from reverse osmosis concentrate using inter-stage ion exchange." (2012). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ce_etds/8 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Engineering ETDs at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Civil Engineering ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Joshua E. Goldman Candidate CIVIL ENGINEERING Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Kerry J. Howe , Chairperson Dr. Bruce M. Thomson Dr. Stephen E. Cabaniss Dr. Jerry Lowry i Selective Salt Recovery from Reverse Osmosis Concentrate Using Inter-stage Ion Exchange BY Joshua E. Goldman B.A., Anthropology, State University of New York at Stony Brook, 2000 M.S, Environmental Science, University of South Florida, 2007 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Engineering The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2012 ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to the loving memory of my grandmother, Henriette Stein. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project was funded by the WateReuse Research Foundation. Resins were donated by ResinTech and Purolite. Francis Boodoo of ResinTech provided technical consultation for the pilot design. -

Appendix A: Distillation and Reverse Osmosis Brine NOD, Phase I

This document is part of Appendix A and includes Distillation and Reverse Osmosis Brine: Nature of Discharge for the “Phase I Final Rule and Technical Development Document of Uniform National Discharge Standards (UNDS),” published in April 1999. The reference number is EPA-842-R-99-001. Phase I Final Rule and Technical Development Document of Uniform National Discharge Standards (UNDS) Distillation and Reverse Osmosis Brine: Nature of Discharge April 1999 NATURE OF DISCHARGE REPORT Distillation and Reverse Osmosis Brine 1.0 INTRODUCTION The National Defense Authorization Act of 1996 amended Section 312 of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (also known as the Clean Water Act (CWA)) to require that the Secretary of Defense and the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) develop uniform national discharge standards (UNDS) for vessels of the Armed Forces for “...discharges, other than sewage, incidental to normal operation of a vessel of the Armed Forces, ...” [Section 312(n)(1)]. UNDS is being developed in three phases. The first phase (which this report supports), will determine which discharges will be required to be controlled by marine pollution control devices (MPCDs)—either equipment or management practices. The second phase will develop MPCD performance standards. The final phase will determine the design, construction, installation, and use of MPCDs. A nature of discharge (NOD) report has been prepared for each of the discharges that has been identified as a candidate for regulation under UNDS. The NOD reports were developed based on information obtained from the technical community within the Navy and other branches of the Armed Forces with vessels potentially subject to UNDS, from information available in existing technical reports and documentation, and, when required, from data obtained from discharge samples that were collected under the UNDS program. -

Reverse Osmosis Brochure

REVERSE OSMOSIS RO Storage Tanks High Purity Water Storage REVERSE OSMOSIS Amtrol invented the pre-pressurized water storage tank over 50 years ago and they are still considered the standard of the industry. These tanks feature a polypropylene liner and butyl diaphragm to prevent water from making contact with the metal tank for cleaner, fresher, better tasting water. All Amtrol RO tanks are manufactured in the USA at our ISO 9001:2008 registered facilities. REVERSE OSMOSIS Tanks • Provide water storage in reverse osmosis water systems. Polypropylene liner and butyl rubber diaphragm • Meet the most demanding specifications for are locked together with potable water. Amtrol’s unique hoop ring • Reliable diaphragm vs. bladder design. and groove design. • Individually tested for safety. ® Durable steel tank for • Available with Pro-Access stainless steel extra-long life. system connection. Typical Installation Cold Hot Drain Line Water Water Line Line Recirculation Line RO Water Membrane Feed Reverse Osmosis Water Storage Tank Pre Post Filter Filter Specifications and Tank Selection A Under Sink Models System Tank A B Tank Shipping Model Connection1 Tank Stand Model Volume Diameter Height Precharge Weight Number NPTM Color Type (Gallons) (Inches) (Inches) (psi) (lbs.) B (Inches) RO-2 140-32 2.0 8 13 ¼ Blue 5 Plastic 5 RO-2 140-653 2.0 8 13 ¼ Blue 20 Plastic 5 Standard RO-3 140S723 3.2 9 15 ¼ White 5 Plastic 7 RO-3 140S725 3.2 9 14 ¼ White 5 3 Bumps 7 A RO-4 141S343 4.4 11 15 ¼ Blue 5 Plastic 9 RO-4 141S344 4.4 11 15 ¼ White 5 Plastic 9 RO-4 141S351 4.4 11 15 ¼ White 5 3 Bumps/Plastic 9 B RO-4 141S352 4.4 11 15 ¼ Blue 5 3 Bumps/Plastic 9 RO-10 143-132 10.0 15 18 ¾ Blue 5 Plastic 20 1 Stainless Steel System Connection. -

21 Reverse Osmosis Treatment of PDWS 03-09

PRIVATE DRINKING WATER IN CONNECTICUT Publication Date: March 2009 Publication No. 21: Reverse Osmosis Treatment of Private Drinking Water Systems Effective Against: inorganic contaminants such as: dissolved salts of sodium, dissolved (ferrous) iron, nitrate, lead, fluoride, sulfate, potassium, manganese, aluminum, silica, chloride, total dissolved solids, chromium, and orthophosphate. Also effective in removing some detergents, some taste, color and odor-producing chemicals, certain organic contaminants, uranium, and some pesticides. Not Effective Against: dissolved gases, most volatile and semi-volatile organic contaminants including some pesticides and solvents. Alone, reverse osmosis (RO) units are not recommended for treatment of bacteria and other microscopic organisms. How Reverse Osmosis Works A complete reverse osmosis system consists of a RO module, a storage tank, and a separate faucet. The module contains a semi-permeable membrane that allows water to selectively pass through and collect in the storage tank. The contaminants being treated by the RO unit are rejected and then washed off the membrane into a waste stream. It is not practical to treat all water entering a home with an RO system because about 75 percent of the water introduced is wasted. Thus, four gallons of raw water into the system produce about one gallon of treated water. This treated water comes out much slower than water from a regular tap, so a tank is used to store the treated water. The treated water is often used only for drinking and cooking. Each manufacturer’s RO units differ, but the time needed to produce one gallon of water ranges from 2-78 hours. The volume of wastewater produced by RO systems varies by make and model. -

Seawater Desalination for Agriculture by Integrated Forward and Reverse Osmosis: Improved Product Water Quality for Potentially Less Energy

Journal of Membrane Science 415–416 (2012) 1–8 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Membrane Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/memsci Perspective Seawater desalination for agriculture by integrated forward and reverse osmosis: Improved product water quality for potentially less energy Devin L. Shaffer a, Ngai Yin Yip a, Jack Gilron b,1, Menachem Elimelech a,n a Department of Chemical and Environmental Engineering, Yale University, P.O. Box 208286, New Haven, CT 06520-8286, USA b Zuckerberg Institute for Water Research, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Sde Boker 84990, Israel article info abstract Article history: Seawater desalination for agricultural irrigation will be an important contributor to satisfying growing Received 21 March 2012 water demands in water scarce regions. Irrigated agriculture for food production drives global water Received in revised form demands, which are expected to increase while available supplies are further diminished. Implementa- 6 May 2012 tion of reverse osmosis, the current leading technology for seawater desalination, has been limited in Accepted 7 May 2012 part because of high costs and energy consumption. Because of stringent boron and chloride standards Available online 15 May 2012 for agricultural irrigation water, desalination for agriculture is more energy intensive than desalination Keywords: for potable use, and additional post-treatment, such as a second pass reverse osmosis process, is Seawater desalination required. In this perspective, we introduce the concept of an integrated forward osmosis and reverse Forward osmosis osmosis process for seawater desalination. Process modeling results indicate that the integrated Integrated process process can achieve boron and chloride water quality requirements for agricultural irrigation while Boron Agriculture consuming less energy than a conventional two-pass reverse osmosis process. -

Aquarius Salinity & Density Bead Activity

Floating in a Salty Sea JPL Aquarius Workshop Background If there is one thing that just about everyone knows about the ocean, it’s that it is salty. The two most common elements in sea water, after oxygen and hydrogen, are sodium and chloride. Sodium and chloride combine to form what we know as table salt. If you allow the wind to dry your skin after swimming in the ocean, you will see a light coasting of salt that has been left behind when the water evaporated. Salinity is a measure of how much salt is in the water. Sea water salinity is expressed as a ratio of salt (in grams) to liter of water. In sea water there is typically close to 35 grams of dissolved salts in each liter. Scientists describe salinity using Practical Salinity Units (PSU) which defines salinity in terms of a conductivity ratio, so it is dimensionless. Salinity was formerly expressed in terms of parts per thousand or by weight (written as ppt or ‰). That is, a salinity of 35 ppt meant 35 grams of salt per 1,000 ml (1 liter) of sea-water. The normal range of open ocean salinity is between 32-37 grams per liter (32‰ - 37‰). Salinity affects density. Density is the mass per unit volume (mass/volume) of a substance. Salty waters are denser than fresh water at the same temperature. Both salt and temperature are important influences on density: density increases with increased salinity and decreases with increased temperature. As you might expect, in the ocean there are areas of high and low salinity. -

Treatment of Municipal Wastewater Reverse Osmosis Concentrate Using Biological Activated Carbon Based Processes

Treatment of Municipal Wastewater Reverse Osmosis Concentrate using Biological Activated Carbon based Processes A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Shovana Pradhan Master of Engineering (Civil/Environmental), Asian Institute of Technology (AIT), Thailand School of Civil, Environmental and Chemical Engineering College of Science, Engineering and Health RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia November, 2016 Declaration I hereby declare that: • the work presented in this thesis is my own work except where due acknowledgement has been made; • the work has not been submitted previously, in whole or in part, to qualify for any other academic award; • the content of the thesis is the result of work which has been carried out since the official commencement date of the approved research program. .............................. (Shovana Pradhan) ........../........../.......... 1 Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere thanks and deep gratitude to my senior supervisor, Dr. Linhua Fan who has kindly given me the opportunity to pursue PhD study under his constant guidance. This thesis would have not been possible without his continuous encouragement, constructive feedback, invaluable advice and scientific inputs. Secondly, I would like to thank Prof. Felicity Roddick as my second supervisor, for her generous support, insightful counsel throughout my study period. She has been extremely motivating, encouraging and positive to my research work. The timely and constructive feedback from my supervisors helped me to improve the quality of my work, as well as professional development during my PhD work. I am grateful for providing scholarship to pursue my PhD by RMIT University. I would like to thank Prof. -

Water Quality Salinity Standards

Water quality standards Electrical conductivity is a measure of the saltiness of the water and is measured on a scale from 0 to 50,000 uS/cm. Electrical conductivity is measured in microsiemens per centimeter (uS/cm). Freshwater is usually between 0 and 1,500 uS/cm and typical sea water has a conductivity value of about 50,000 uS/cm. Low levels of salts are found naturally in waterways and are important for plants and animals to grow. When salts reach high levels in freshwater it can cause problems for aquatic ecosystems and complicated human uses. μS/cm Use 0 - 800 • Good drinking water for humans (provided there is no organic pollution and not too much suspended clay material) • Generally good for irrigation, though above 300μS/cm some care must be, particularly with overhead sprinklers, which may cause leaf, scorch on some salt sensitive plants. • Suitable for all livestock 800 - 2500 • Can be consumed by humans, although most would prefer water in the lower half of this range if available • When used for irrigation, requires special management including suitable soils, good drainage and consideration of salt tolerance of plants • Suitable for all livestock 2500 -10,000 • Not recommended for human consumption, although water up to 3000 μS/cm can be consumed • Not normally suitable for irrigation, although water up to 6000 μS/cm can be used on very salt tolerant crops with very special management techniques. Over 6000 μS/cm, occasional emergency may be possible with care • When used for drinking water by poultry and pigs, the salinity should be limited to about 6000 μS/cm.