A Methodological Approach to Utilize Egyptian Colloquial Arabic As a Source for Ancient Egyptian Linguistic Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timeline .Pdf

Timeline of Egyptian History 1 Ancient Egypt (Languages: Egyptian written in hieroglyphics and Hieratic script) Timeline of Egyptian History 2 Early Dynastic Period 3100–2686 BCE • 1st & 2nd Dynasty • Narmer aka Menes unites Upper & Lower Egypt • Hieroglyphic script developed Left: Narmer wearing the crown of Lower Egypt, the “Deshret”, or Red Crown Center: the Deshret in hieroglyphics; Right: The Red Crown of Lower Egypt Narmer wearing the crown of Upper Egypt, the “Hedjet”, or White Crown Center: the Hedjet in hieroglyphics; Right: The White Crown of Upper Egypt Pharaoh Djet was the first to wear the combined crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, the “Pschent” (pronounced Pskent). Timeline of Egyptian History 3 Old Kingdom 2686–2181 BCE • 3rd – 6th Dynasty • First “Step Pyramid” (mastaba) built at Saqqara for Pharaoh Djoser (aka Zoser) Left: King Djoser (Zoser), Righr: Step pyramid at Saqqara • Giza Pyramids (Khufu’s pyramid – largest for Pharaoh Khufu aka Cheops, Khafra’s pyramid, Menkaura’s pyramid – smallest) Giza necropolis from the ground and the air. Giza is in Lower Egypt, mn the outskirts of present-day Cairo (the modern capital of Egypt.) • The Great Sphinx built (body of a lion, head of a human) Timeline of Egyptian History 4 1st Intermediate Period 2181–2055 BCE • 7th – 11th Dynasty • Period of instability with various kings • Upper & Lower Egypt have different rulers Middle Kingdom 2055–1650 BCE • 12th – 14th Dynasty • Temple of Karnak commences contruction • Egyptians control Nubia 2nd Intermediate Period 1650–1550 BCE • 15th – 17th Dynasty • The Hyksos come from the Levant to occupy and rule Lower Egypt • Hyksos bring new technology such as the chariot to Egypt New Kingdom 1550–1069 BCE (Late Egyptian language) • 18th – 20th Dynasty • Pharaoh Ahmose overthrows the Hyksos, drives them out of Egypt, and reunites Upper & Lower Egypt • Pharaoh Hatshepsut, a female, declares herself pharaoh, increases trade routes, and builds many statues and monuments. -

Ancient Egyptian Chronology.Pdf

Ancient Egyptian Chronology HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-THREE Ancient Egyptian Chronology Edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2006 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ancient Egyptian chronology / edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton; with the assistance of Marianne Eaton-Krauss. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 83) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-90-04-11385-5 ISBN-10: 90-04-11385-1 1. Egypt—History—To 332 B.C.—Chronology. 2. Chronology, Egyptian. 3. Egypt—Antiquities. I. Hornung, Erik. II. Krauss, Rolf. III. Warburton, David. IV. Eaton-Krauss, Marianne. DT83.A6564 2006 932.002'02—dc22 2006049915 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 11385 1 ISBN-13 978 90 04 11385 5 © Copyright 2006 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

I) If\L /-,7\ .L Ii Lo N\ C, ' II Ii Abstract Approved: 1'

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Asaad AI-Saleh for the Master of Arts Degree In English presented on _------'I'--'I--'J:..=u:o...1VL.c2=0"--'0"-=S'------ _ Title: Mustafa Sadiq al-Rafii: A Non-recognized Voice in the Chorus ofthe Arabic Literary Revival i) If\l /-,7\ .L Ii lo n\ C, ' II Ii Abstract Approved: 1'. C". C ,\,,: 41-------<..<.LI-hY,-""lA""""","""I,--ft-'t _ '" I) Abstract Mustafa Sadiq al-Rafii, a modem Egyptian writer with classical style, is not studied by scholars of Arabic literature as are his contemporary liberals, such as Taha Hussein. This thesis provides a historical background and a brief literary survey that helps contextualize al-Rafii, the period, and the area he came from. AI-Rafii played an important role in the two literary and intellectual schools during the Arabic literary revival, which extended from the French expedition (1798-1801) to around the middle of the twentieth century. These two schools, known as the Old and the New, vied to shape the literature and thought of Egypt and other Arab countries. The former, led by al-Rafii, promoted a return to classical Arabic styles and tried to strengthen the Islamic identity of Egypt. The latter called for cutting off Egypt from its Arabic history and rejected the dominance and continuity of classical Arabic language. AI-Rafii contributed to the Revival by supporting a line ofthought that has not been favored by pro-Westernization governments, which made his legacy almost forgotten. Deriving his literature from the canon of Arabic language, culture, and history, al-Rafii produced a literature based on a revived version of classical Arabic literature, an accomplishment which makes him unique among modem Arab writers. -

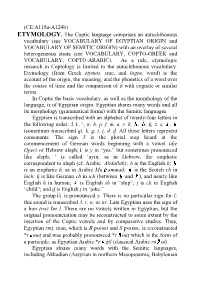

ETYMOLOGY. the Coptic Language Comprises an Autochthonous

(CE:A118a-A124b) ETYMOLOGY. The Coptic language comprises an autochthonous vocabulary (see VOCABULARY OF EGYPTIAN ORIGIN and VOCABULARY OF SEMITIC ORIGIN) with an overlay of several heterogeneous strata (see VOCABULARY, COPTO-GREEK and VOCABULARY, COPTO-ARABIC). As a rule, etymologic research in Coptology is limited to the autochthonous vocabulary. Etymology (from Greek etymos, true, and logos, word) is the account of the origin, the meaning, and the phonetics of a word over the course of time and the comparison of it with cognate or similar terms. In Coptic the basic vocabulary, as well as the morphology of the language, is of Egyptian origin. Egyptian shares many words and all its morphology (grammatical forms) with the Semitic languages. Egyptian is transcribed with an alphabet of twenty-four letters in the following order: 3, „ , ‘, w, b, p, f, m, n, r, h, , , h, z, s, , (sometimes transcribed q), k, g, t, t, d, d. All these letters represent consonants. The sign 3 is the glottal stop heard at the commencement of German words beginning with a vowel (die Oper) or Hebrew aleph; „ is y in “yes,” but sometimes pronounced like aleph; ‘ is called ‘ayin, as in Hebrew, the emphatic correspondent to aleph (cf. Arabic ‘Abdallah); h is the English h; is an emphatic h, as in Arabic Mu ammad; is the Scotch ch in loch; h is like German ch in ich (between and ), and nearly like English h in human; is English sh in “ship”; t is ch in English “child”; and d is English j in ‘joke.” The group „„ is pronounced y. -

Nonconcatenative Morphology in Coptic

UC Santa Cruz Phonology at Santa Cruz, Volume 7 Title Nonconcatenative Morphology in Coptic Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0765s94q Author Kramer, Ruth Publication Date 2018-04-10 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Nonconcatenative Morphology in Coptic ∗∗∗ Ruth Kramer 1. Introduction One of the most distinctive features of many Afroasiatic languages is nonconcatenative morphology. Instead of attaching an affix directly before or after a root, languages like Modern Hebrew interleave an affix within the segments of a root. An example is in (1). (1) Modern Hebrew gadal ‘he grew’ gidel ‘he raised’ gudal ‘he was raised’ In the mini-paradigm in (1), the discontinuous affixes /a a/, /i e/, and /u a/ are systematically interleaved between the root consonants /g d l/ to indicate perfective aspect, causation and voice, respectively. The consonantal root /g d l/ ‘big’ never surfaces on its own in the language: it must be inflected with some vocalic affix. Additional Afroasiatic languages with nonconcatenative morphology include other Semitic languages like Arabic (McCarthy 1979, 1981; McCarthy and Prince 1990), many Ethiopian Semitic languages (Rose 1997, 2003), and Modern Aramaic (Hoberman 1989), as well as non-Semitic languages like Berber (Dell and Elmedlaoui 1992, Idrissi 2000) and Egyptian (also known as Ancient Egyptian, the autochthonous language of Egypt; Gardiner 1957, Reintges 1994). The nonconcatenative morphology of Afroasiatic languages has come to be known as root and pattern -

Egypt: Toponymic Factfile

TOPONYMIC FACT FILE Egypt Country name Egypt1 State title Arab Republic of Egypt Name of citizen Egyptian Official language Arabic (ara2) مصر (Country name in official language 3(Mişr جمهورية مصر العربية (State title in official language (Jumhūrīyat Mişr al ‘Arabīyah Script Arabic Romanization System BGN/PCGN Romanization System for Arabic 1956 ISO-3166 country code (alpha- EG/EGY 2/alpha-3) Capital Cairo4 القاهرة (Capital in official language (Al Qāhirah Geographical Names Policy Geographical names in Egypt are found written in Arabic, which is the country’s official language. Where possible names should be taken from official Arabic-language Egyptian sources and romanized using the BGN/PCGN Romanization System for Arabic5. Roman-script resources are often available for Egypt; however, it should also be noted that, even on official Egyptian products, Roman-script forms may be encountered which are likely to differ from those arising from the application of the BGN/PCGN Romanization System for Arabic.6 There are conventional Roman-script or English-language names for many places in Egypt (see ‘Other significant locations’, p12), which can be used where appropriate. For instance, in an English text it would be preferable to refer to the capital of Egypt as Cairo, and perhaps include a reference to its romanized form (Al Qāhirah). PCGN usually recommends showing these English conventional names in brackets after 1 The English language conventional name Egypt comes from the Ancient Greek Aígyptos (Αἴγυπτος) which is believed to derive from Ancient Egyptian hut-ka-ptah, meaning “castle of the soul of Ptah”. 2 ISO 639-3 language codes are used for languages throughout this document. -

Reformed Egyptian

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 19 Number 1 Article 7 2007 Reformed Egyptian William J. Hamblin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hamblin, William J. (2007) "Reformed Egyptian," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 19 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol19/iss1/7 This Book of Mormon is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Reformed Egyptian Author(s) William J. Hamblin Reference FARMS Review 19/1 (2007): 31–35. ISSN 1550-3194 (print), 2156-8049 (online) Abstract This article discusses the term reformed Egyptian as used in the Book of Mormon. Many critics claim that reformed Egyptian does not exist; however, languages and writing systems inevitably change over time, making the Nephites’ language a reformed version of Egyptian. Reformed Egyptian William J. Hamblin What Is “Reformed Egyptian”? ritics of the Book of Mormon maintain that there is no language Cknown as “reformed Egyptian.” Those who raise this objec- tion seem to be operating under the false impression that reformed Egyptian is used in the Book of Mormon as a proper name. In fact, the word reformed is used in the Book of Mormon in this context as an adjective, meaning “altered, modified, or changed.” This is made clear by Mormon, who tells us that “the characters which are called among us the reformed Egyptian, [were] handed down and altered by us” and that “none other people knoweth our language” (Mormon 9:32, 34). -

'That' in the GRAMMAR of EGYPTIAN ARABIC Rehab Gad

THE ROLE OF illi ‘that’ IN THE GRAMMAR OF EGYPTIAN ARABIC Rehab Gad Abstract This paper investigates the role of illi in the grammar of one of the colloquial dialects of Arabic; that is Egyptian Arabic (EA). It investigates how illi affects the formation of wh- questions (with initial and in-situ wh-phrases) and relative clauses. Since the classification of illi has been a subject of debate in the literature, the study aims at providing a new analysis for it. The major claim is that illi belongs to the class of functional categories which serves the grammatical function of a relative pronoun. This paper presents data where illi acts as both a relative pronoun and a licensor for wh-fronting. The following questions are addressed: 1. If illi is analysed as a relative pronoun, how can we account for its occurrence in an initial position within some wh-questions without having to propose a movement analysis? 2. Can illi be classified as a complementizer that shares some syntactic properties with the complementizer inn ‘that‟? 3. Within wh-questions, does illi behave as a question particle? 4. How can we account for the EA data where illi has the dual function of a relative pronoun and a complementizer? The major claim is that illi does not belong to the class of question particles which mark a yes/no question and a wh-question. Though illi and inn „that‟ occur as C elements equivalent to the English „that‟, illi does not exhibit the morphological or the functional properties of inn „that‟, hence it cannot be classified as a complementizer. -

Bulletin De L'institut Français D'archéologie Orientale

MINISTÈRE DE L'ÉDUCATION NATIONALE, DE L'ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE BULLETIN DE L’INSTITUT FRANÇAIS D’ARCHÉOLOGIE ORIENTALE en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne BIFAO 114 (2014), p. 455-518 Nico Staring The Tomb of Ptahmose, Mayor of Memphis Analysis of an Early 19 th Dynasty Funerary Monument at Saqqara Conditions d’utilisation L’utilisation du contenu de ce site est limitée à un usage personnel et non commercial. Toute autre utilisation du site et de son contenu est soumise à une autorisation préalable de l’éditeur (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). Le copyright est conservé par l’éditeur (Ifao). Conditions of Use You may use content in this website only for your personal, noncommercial use. Any further use of this website and its content is forbidden, unless you have obtained prior permission from the publisher (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). The copyright is retained by the publisher (Ifao). Dernières publications 9782724708288 BIFAO 121 9782724708424 Bulletin archéologique des Écoles françaises à l'étranger (BAEFE) 9782724707878 Questionner le sphinx Philippe Collombert (éd.), Laurent Coulon (éd.), Ivan Guermeur (éd.), Christophe Thiers (éd.) 9782724708295 Bulletin de liaison de la céramique égyptienne 30 Sylvie Marchand (éd.) 9782724708356 Dendara. La Porte d'Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724707953 Dendara. La Porte d’Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724708394 Dendara. La Porte d'Hathor Sylvie Cauville 9782724708011 MIDEO 36 Emmanuel Pisani (éd.), Dennis Halft (éd.) © Institut français d’archéologie orientale - Le Caire Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) 1 / 1 The Tomb of Ptahmose, Mayor of Memphis Analysis of an Early 19 th Dynasty Funerary Monument at Saqqara nico staring* Introduction In 2005 the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acquired a photograph taken by French Egyptologist Théodule Devéria (fig. -

Download Date 04/10/2021 06:40:30

Mamluk cavalry practices: Evolution and influence Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Nettles, Isolde Betty Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 06:40:30 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/289748 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this roproduction is dependent upon the quaiity of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that tfie author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g.. maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal secttons with small overlaps. Photograpiis included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrattons appearing in this copy for an additk)nal charge. -

Who Was Who at Amarna

1 Who was Who at Amarna Akhenaten’s predecessors Amenhotep III: Akhenaten’s father, who ruled for nearly 40 years during the peak of Egypt’s New Kingdom empire. One of ancient Egypt’s most prolific builders, he is also known for his interest in the solar cult and promotion of divine kingship. He was buried in WV22 at Thebes, his mummy later cached with other royal mummies in the Tomb of Amenhotep II (KV 35) in the Valley of the Kings. Tiye: Amenhotep III’s chief wife and the mother of Akhenaten. Her parents Yuya and Tjuyu were from the region of modern Akhmim in Egypt’s south. She may have lived out her later years at Akhetaten and died in the 14th year of Akhenaten’s reign. Funerary equipment found in the Amarna Royal Tomb suggests she was originally buried there, although her mummy was later moved to Luxor and is perhaps to be identified as the ‘elder lady’ from the KV35 cache. Akhenaten and his family Akhenaten: Son and successor of Amenhotep III, known for his belief in a single solar god, the Aten. He spent most of his reign at Akhetaten (modern Amarna), the sacred city he created for the Aten. Akhenaten died of causes now unknown in the 17th year of his reign and was buried in the Amarna Royal Tomb. His body was probably relocated to Thebes and may be the enigmatic mummy recovered in the early 20th century in tomb KV55 in the Valley of the Kings. Nefertiti: Akhenaten’s principal queen. Little is known of her background, although she may also have come from Akhmim. -

Ancient Egypt: Symbols of the Pharaoh

Ancient Egypt: Symbols of the pharaoh Colossal bust of Ramesses II Thebes, Egypt 1250 BC Visit resource for teachers Key Stage 2 Ancient Egypt: Symbols of the pharaoh Contents Before your visit Background information Resources Gallery information Preliminary activities During your visit Gallery activities: introduction for teachers Gallery activities: briefings for adult helpers Gallery activity: Symbol detective Gallery activity: Sculpture study Gallery activity: Mighty Ramesses After your visit Follow-up activities Ancient Egypt: Symbols of the pharaoh Before your visit Ancient Egypt: Symbols of the pharaoh Before your visit Background information The ancient Egyptians used writing to communicate information about a person shown on a sculpture or relief. They called their writing ‘divine word’ because they believed that Thoth, god of wisdom, had taught them how to write. Our word hieroglyphs derives from a phrase meaning ‘sacred carvings’ used by the ancient Greek visitors to Egypt to describe the symbols that they saw on tomb and temple walls. The number of hieroglyphic signs gradually grew to over 7000 in total, though not all of them were used on a regular basis. The hieroglyphs were chosen from a wide variety of observed images, for example, people, birds, trees, or buildings. Some represent the sounds of the ancient Egyptian language, but consonants only. No vowels were written out. Also, it was not an alphabetic system, since one sign could represent a combination of two or more consonants like the gaming-board hieroglyph which stands for the consonants mn. Egyptologists make the sounds pronounceable by putting an e between the consonants, so mn is read as men.