I. Visitation in the New York Chaplaincy Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chaplaincy in Anglican Schools

CHAPLAINCY IN ANGLICAN SCHOOLS GUIDELINES FOR THE CONSIDERATION OF BISHOPS, HEADS OF SCHOOLS, CHAPLAINS, AND HEADS OF THEOLOGICAL COLLEGES THE REVEREND DR TOM WALLACE ON BEHALF OF THE AUSTRALIAN ANGLICAN SCHOOLS NETWORK ANGLICAN CHURCH OFFICE 26 KING WILLIAM ROAD NORTH ADELAIDE SA 5006 AUGUST 1999 1 CHAPLAINCY IN ANGLICAN SCHOOLS GUIDELINES FOR BISHOPS, HEADS OF SCHOOLS AND CHAPLAINS 1. BACKGROUND At the National Anglican Schools Conference held at Melbourne Girls’ Grammar in April 1997 the National Anglican Schools Consultative Committee was asked to conduct a survey on Religious Education and Chaplaincy in Anglican schools in Australia. The Survey was conducted on behalf of the Committee by Dr Peter Coman, Executive Director of the Anglican Schools Office in the Diocese of Brisbane in February 1998. An Interim Report was presented to the National Conference in May 1998. The Rev’d Dr Tom Wallace of the Anglican Schools Commission in Western Australia was asked to give consideration to ways in which the Report may be followed up and a small consultative committee, representative of all the States, was appointed to work with him. It was agreed that Dr Wallace would prepare a discussion paper on Chaplaincy in Anglican Schools, which would be considered initially by members of the representative committee with a view to wider circulation to Principals, Chaplains and Diocesan Bishops. That discussion paper was prepared and feedback on it was received from several Chaplains from three Australian States. As a result of the feedback the Paper was revised with a view to it being considered at a national gathering of Chaplains at the National Anglican Schools Conference in May 1999. -

The History of the New York State Association of Fire Chaplains, Inc

The History of the New York State Association of Fire Chaplains, Inc. Celebrating the Association’s 2016 (Updated October 7, 2017) Table of Contents SS Dorchester .............................................................................................. 3 Chaplains’ Seminar at FASNY - 1966 ......................................................... 4 Incorporation ................................................................................................ 7 Support of Fire Chiefs and FASNY .............................................................. 8 Chaplain’s Manual........................................................................................ 8 1970’s Conferences ..................................................................................... 9 Fire Academy Established ........................................................................... 9 Women in Fire Service ............................................................................... 10 1980’s Conferences ................................................................................... 10 Lay Chaplains ............................................................................................ 11 1994 - Lay Chief Chaplain ......................................................................... 12 2000’s Conferences ................................................................................... 14 FASNY Chaplains’ Committee ................................................................... 16 Marriage Renewal Service - 2006 ............................................................ -

Standards for the Work Of. the .Chaplain in the General Hospital

fillicia11y Adopted by the Am . .Ptot..estant H09P,;+~ 1 A encal1 '.B' _Lal. BSll. at th . OBton Conven~ion c_ te be Q v. ~p m r 194(}. Standards for the Work of. the .Chaplain in the General Hospital REV. RUSSELL L. DICKS, D.O. T has come to the attention of the American The Author Protestant Hospital Association that the • Rev. Russell L. Dicks, D.D., is Chaplain I spiritual needs of many patients, both in pri of the Presbyterian Hospital, Chic~go, and vate and public institutions, are not receiving Chairman of the Special Study Committee proper attention. In some instances patients are that prepared these Standards. not receiving any spiritual care, in others they are receiving altogether too much. We know of with the clergyman's ordination vows or his institutions where as many as seven or eight higher loyalties. different religious workers may speak to the same patient in a given afternoon while hundreds of In the past when treatment of the soul was other patients in the same institution receive no considered as apart from medical care of the pa ,. attention. It has also come to our attention that tient; and was believed to have nothing to do with many religious workers in hospitals attempt to his health, the hospital and the physician were force their own religious views upon the patient not greatly concerned with the spiritual condition whether he desires them or not. of the patient, although some medical men have always recognized a close alliance between body It is our hope that through the following sug and soul. -

Housing Allowance and Other Clergy Tax Issues Revised December 2015

Housing Allowance and Other Clergy Tax Issues Revised December 2015 By Dennis R. Walsh, CPA This is a summary of special income tax issues applicable to clergy employed by units of government and serving in other non-traditional settings. All information provided is intended for educational purposes. As laws are constantly changing, the reader should seek competent guidance as necessary and be aware of applicable legislative, administrative, and judicial action that may have occurred since preparation of this document. Q1: When is an individual a minister for tax purposes? Whether the services of a duly ordained, licensed, or commissioned clergyperson are classified as in the “exercise of ministry” for federal tax purposes determines if tax rules unique to clergy are applicable. o For services other than as an employee of a theological seminary or church- controlled organization, in order to be considered in the exercise of ministry the services must involve either: o The ministration of sacerdotal functions (.e.g. communion, baptism, funerals, etc.), or o The conduct of religious worship The following should also be considered: o The determination of what constitutes the performance of “sacerdotal functions” and the conduct of religious worship depends on the tenets and practices of the individual’s church. Treas. Reg. § 1.1402(c)-5(b)(2)(i). o A minister who is performing the conduct of worship and ministration of sacerdotal functions is performing service in the exercise of his/her ministry, whether or not these services are performed for a religious organization. Treas. Reg. § 1.1402(c)-5(b)(2)(iii). o The service of a chaplain in the Armed Forces is considered to be those of a commissioned officer and not in the exercise of his or her ministry. -

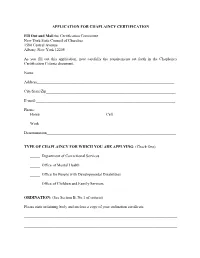

APPLICATION for CHAPLAINCY CERTIFICATION Fill out and Mail To

APPLICATION FOR CHAPLAINCY CERTIFICATION Fill Out and Mail to: Certification Committee New York State Council of Churches 1580 Central Avenue Albany, New York 12205 As you fill out this application, note carefully the requirements set forth in the Chaplaincy Certification Criteria document. Name________________________________________________________________________ Address______________________________________________________________________ City/State/Zip__________________________________________________________________ E-mail:_______________________________________________________________________ Phone: Home__________________________________Cell________________________________ Work______________________________________________________________________ Denomination__________________________________________________________________ TYPE OF CHAPLAINCY FOR WHICH YOU ARE APPLYING: (Check One) _____ Department of Correctional Services _____ Office of Mental Health _____ Office for People with Developmental Disabilities _____ Office of Children and Family Services ORDINATION: (See Section B, No.1 of criteria) Please state ordaining body and enclose a copy of your ordination certificate. ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ OFFICIAL ECCLESIASTICAL ENDORSEMENT: (Section B, No.2 of criteria) Give name of agency or official authorized by your denomination to endorse its clergy for chaplaincy positions. (This agency or person -

800 Navy Chaplains

A calling within a calling CHAPLAIN CHAPLAIN The ability to minister outside of the conventional setting. NAVY POLICY Navy Chaplains are expected to support and ensure the free The chance to interact with members of diverse faith practice of religion for all. Therefore, you must be: groups. The opportunity to make a profound difference in • Willing to function in the diverse and pluralistic environment of the military the lives of individuals on a regular basis. These are some • Tolerant of diverse religious traditions of the things that make the work of Navy Chaplains so • Respectful of the rights of individuals to determine their own religious convictions rewarding and so unique. The specialized environment of the military requires Navy Chaplains The Navy Chaplain Corps is made up of over 800 Navy Chaplains. Chaplains confirm more to embrace these guidelines without compromising the tenets of than 100 different faith groups currently represented (Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist their own religious traditions. Also, it is important to note that and many others). Each Chaplain is also a Navy Officer – meaning each holds an important Navy Chaplains are officially considered noncombatants and not leadership role. authorized to bear arms. Together, Navy Chaplains enable the free practice of religion for all the Sailors, Marines and NOTES Coast Guardsmen who serve. But their impact goes far beyond the mere exercise of religion. JOB DESCRIPTION As a Navy Chaplain, you will nurture the spiritual well-being of those around you. Living with them. Working with them. Eating with them. Praying with them. Understanding their needs and challenges like no one else – in a ministry that is truly 24/7. -

Chaplains in Canon Law and Contemporary Practice

C A N O N L A W CHAPLAINS IN CANON LAW AND CONTEMPORARY PRACTICE anon law defines a chaplain as “a priest to whom is entrusted in a stable manner the pastoral care, at least in part, of some community or special group of Christ’s faithful, C to be exercised in accordance with universal and particular law” (Canon 564). The law establishes the chaplain as a canonical figure in the person of a priest who is account- able to the diocesan bishop. A deacon cannot be named a chaplain in the canonical sense. “Stable manner” implies the Consultation between the local ordinary formal appointment to a par- and a religious superior in a house of a lay reli- ticular group associated with gious institute before appointing a chaplain for various apostolates such as the purpose of directing liturgical functions (567 educational institutions or ser- gives the superior the right to propose a particu- vices with long-standing social lar priest) traditions such as prisons or Appointment of chaplains for those who are hospitals. The office is no lon- not able to avail themselves of the ordinary care SR. MARLENE ger linked to foundations or of parish priests, e.g. migrants, exiles, fugitives, WEISENBECK non-parochial churches as was nomads, seafarers (568) and armed forces (569) the practice in the past. “Pas- which must take into account state relationships toral care” refers to the role of with armed forces the priest having a canonical office for full care Circumstances in which a non-parochial of souls, which includes preaching, sacramental church is attached to a center of a community or minister of baptism, penance, anointing of the group (570) sick, marriage, Eucharist and celebration of the The requirement of the chaplain to maintain Mass. -

Finding the Balance in Chaplain Roles As Both Clergy and Military Officers

Volume 89 • Number 2 • Summer 2016 Finding the balance in chaplain roles as both clergy and military officers “Voices of Chaplaincy” Book Series – Your Stories Needed The Military Chaplains Association is seeking short, personal stories of chaplain ministry from MCA members in the core ministry functions of nurturing the living, caring for the wounded, and honoring the fallen. Help the MCA share and preserve the inspirational stories of chaplains who served or currently serve in the U.S. Armed Forces, Civil Air Patrol and VA Chaplain Service. Stories will be compiled, edited and published by MCA in paperback and e-book format and made available for worldwide distribution. All proceeds from book sales will benefit the MCA Chaplain Candidate Scholarship Fund. This new book series will expand the ability of the MCA to mentor and connect chaplains as we tell our story as personal advocates and voices of chaplaincy. Stories should be limited to 500-1000 words (2-3 double-spaced pages) and specifically focus on one of the three core ministry functions. You may submit more than one story. All submissions are subject to approval by the editorial board. See below for more information and helpful guidelines for writing your story. If you have further questions, please send an email to: [email protected] Helpful Guidelines for Writing Your Story 1. Keep your story clear and concise. State the facts but avoid revealing any personal or confidential details (names of certain individuals, security sensitive info, etc.) that would detract from your story. 2. Limit your story to 500-1000 words or less (about 2-3 double-spaced pages if using 12 point New Times Roman font). -

Military Chaplain History

A Brief History of American Military Chaplains and their Connection with Methodism in the Anchorage Alaska Community June 2007 Larry Hayden Commission on Archives and History Alaska Missionary Conference The United Methodist Church 1 Table of Contents Page Number Table of Contents ………………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements …………………………………………………….. x Early History …………………………………………………………… x The 1940s -- World War II ……………………………………………… x Chaplain Assistants ……………………………………………………… x The 1950s -- Korean Conflict …………………………………………… x Retreats …………………………………………………………………. x Women’s Commissioning ……………………………………………… x The UMT (Unit Ministry Team) …………………………………………. x The 1980s ………………………………………………………………… x The Alaska Connection ………………………………………………… y Fort Richardson Beginnings …………………………………………… y Community Relations ………………………………………………….. y Alaska Missionary Conference Journal Reports ………………………… y Appendixes …………………………………………………………….. z Four Chaplains Military Chaplains Association The Covenant and the Code of Ethics for Chaplains of the Armed Forces Protestant Women of the Chapel Official Qualifications and Some Historical Chaplain Duties Corporate Chaplains of America Citations and Sources for Continued Research Statement on Public Prayer in the Navy Officers, Soldiers, and God Miscellaneous items Why I Am A Chaplain – United Methodist Endorsing Agency 2 The original title of this booklet, Soldiers of God, was changed so that readers would not be confused with any reference to the mujahidin Islamic Warriers of Afghanistan and Pakistan who where fighting the Soviets, or to the White Supremacists of the White Camelia Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. It does not have any relation to the Salvation Army terminology. It was chosen because of its identifying nature and is referenced in the Chaplain’s report in the Alaska Missionary Conference Annual Journal of 1962, printed on page 81 of the Journal. The photograph on the front cover of this booklet was taken in the late 1950s on Elmendorf Air Force Base. -

Navy Chaplain Corps

UNITED STATES NAVY Chaplain Corps 1,000,000 men, women and children are seeking spiritual guidance and religious accommodation. Does impacting the lives of young leaders strike a chord in your soul? Are you up to the challenge? Your ministry will have a profound and enduring effect on the men and women of the Sea Services. Navy Chaplains enjoy unparalleled opportunities to serve God and country while ministering to people of diverse and dynamic settings. Chaplains provide spiritual guidance: Ministering to those in need anywhere, any time; On beaches or in the field, conducting service from the back of a truck; In Navy chapels worldwide; At sea leading services and classes on the most modern ships afloat; Benefits Offered Vision, Medical, Life, Dental, 401K Employment Type Full-Time (Active Duty) Part-Time (Reserve) HOW TO BECOME A CHAPLAIN Clergy can become Navy chaplains: Active Duty: commissioned with a minimum of three years of Active service. Reserve Duty: commissioned with a commitment to attend two day monthly drills plus two weeks of annual training for a minimum of three years Reserve service, while remaining in their civilian careers. Chaplain Candidates: after completing the requirements in the CCPO program, Chaplain Candidates may apply to become an Active or Reserve Chaplain. OPPORTUNITIES TO SERVE Navy Chaplains serve with all members of the Sea Services: Navy Marine Corps Coast Guard Merchant Marine Because the Marine Corps, Coast Guard, and Merchant Marines do not have their own Chaplain Corps, Navy Chaplains find themselves assigned in many different duty stations, including: ship, shore, air wing and infantry, from polar regions to the equator. -

Anglican Chaplain

The Diocese of Coventry and The University of Warwick Anglican Chaplain Background The University of Warwick is widely recognised as one of the UK’s leading Universities. Ranked 3rd in the world amongst the top 50 universities under 50 years of age (QS table for 2013 and 2014), it is a teaching and research community of approximately 24,000 students and 5000 staff, led by Vice-Chancellor Professor Nigel Thrift. The Chaplaincy Centre, situated at the very heart of the campus, serves as a place of welcome, meeting, engagement, prayer and stillness within the busy campus community. With a significant contingent of international students (approximately one-third of the overall student population), the community is a diverse one. As part of the worldwide Coventry Cross of Nails community, the Chaplaincy works with Coventry Cathedral to build peace through understanding. Promoting tolerance and reconciliation, the Chaplaincy proudly celebrates Warwick’s diversity. The Diocese of Coventry covers Coventry, Warwickshire and a part of Solihull and is led by the ninth Bishop of Coventry, the Right Reverend Dr Christopher Cocksworth. The themes of Peace and Reconciliation form a distinctive part of the heritage of the city, Cathedral, Diocese of Coventry, and the University. Coventry Cathedral has a world renowned reputation for promoting peace and reconciliation, and the Chaplaincy, as part of the Cross of Nails community, seeks to embody and share this calling within the university community. The Chaplaincy is both a place and a team of people, serving students and staff of all faiths and none. A recent (2012/13) review of the Chaplaincy underlines the outstanding contribution that the work of the Chaplaincy makes to the University community. -

Chaplaincy Australia Constitution 2008

Chaplaincy Australia Incorporated Articles of Constitution 1 AUTHORITY Pursuant to the provisions of the United Constitution of the Assemblies of God in Australia (Article 16), Chaplaincy Australia Inc shall be responsible to the NSW Assemblies of God State Conference for the Chaplaincy program of the State Fellowship and to this end shall set up as a State Department. 2 NAME The name shall be Chaplaincy Australia Incorporated. 3 VISION We envisage a dynamic, Christ-honouring, network of Chaplains in Australia with an unshakeable commitment to both the Great Commission and the Great Commandment. "But you shall receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you shall be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth.” Acts 1:8 NKJV We believe that the Lord Jesus left His Church with two foundational commands. One, we have come to know as… The Great Commission… the other, we refer to as The Great Commandment. The Great Commission This is our call to impact our generation. Beginning in … * Jerusalem ... locally... * Judea ... nationally... * Samaria ... cross – culturally... * The ends of the Earth ... internationally... The Great Commandment Jesus declared that there was no greater commandment than to... “Love the Lord your God, with all your heart, all your soul, and all your mind... and to love your neighbour as yourself.” Therefore, we seek to impact our cities and beyond by actively demonstrating the love of Christ (Great Commandment) through contemporary and relevant chaplaincy ministries designed to reach and influence (Great Commission) all levels of society with the life-changing gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ.