Keeping Venomous Snakes Procedure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines for Keeping Venomous Snakes in the NT

GUIDELINES FOR KEEPING VENOMOUS SNAKES IN THE NT Venomous snakes are potentially dangerous to humans, and for this reason extreme caution must be exercised when keeping or handling them in captivity. Prospective venomous snake owners should be well informed about the needs and requirements for keeping these animals in captivity. Permits The keeping of protected wildlife in the Northern Territory is regulated by a permit system under the Territory Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 2006 (TPWC Act). Conditions are included on permits, and the Parks and Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory (“PWCNT”) may issue infringement notices or cancel permits if conditions are breached. A Permit to Keep Protected Wildlife enables people to legally possess native vertebrate animals in captivity in the Northern Territory. The permit system assists the PWCNT to monitor wildlife kept in captivity and to detect any illegal activities associated with the keeping of, and trade in, native wildlife. Venomous snakes are protected throughout the Northern Territory and may not be removed from the wild without the appropriate licences and permits. People are required to hold a Keep Permit (Category 1–3) to legally keep venomous snakes in the Northern Territory. Premises will be inspected by PWCNT staff to evaluate their suitability prior to any Keep Permit (Category 1– 3) being granted. Approvals may also be required from local councils, the Northern Territory Planning Authority, and the Department of Health and Community Services. Consignment of venomous snakes between the Northern Territory and other States and Territories can only be undertaken with an appropriate import / export permit. There are three categories of venomous snake permitted to be kept in captivity in the Northern Territory: Keep Permit (Category 1) – Mildly Dangerous Venomous Keep Permit (Category 2) – Dangerous Venomous Keep Permit (Category 3) – Highly Dangerous Venomous Venomous snakes must be obtained from a legal source (i.e. -

Controlled Animals

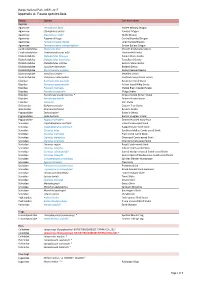

Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Policy Division Controlled Animals Wildlife Regulation, Schedule 5, Part 1-4: Controlled Animals Subject to the Wildlife Act, a person must not be in possession of a wildlife or controlled animal unless authorized by a permit to do so, the animal was lawfully acquired, was lawfully exported from a jurisdiction outside of Alberta and was lawfully imported into Alberta. NOTES: 1 Animals listed in this Schedule, as a general rule, are described in the left hand column by reference to common or descriptive names and in the right hand column by reference to scientific names. But, in the event of any conflict as to the kind of animals that are listed, a scientific name in the right hand column prevails over the corresponding common or descriptive name in the left hand column. 2 Also included in this Schedule is any animal that is the hybrid offspring resulting from the crossing, whether before or after the commencement of this Schedule, of 2 animals at least one of which is or was an animal of a kind that is a controlled animal by virtue of this Schedule. 3 This Schedule excludes all wildlife animals, and therefore if a wildlife animal would, but for this Note, be included in this Schedule, it is hereby excluded from being a controlled animal. Part 1 Mammals (Class Mammalia) 1. AMERICAN OPOSSUMS (Family Didelphidae) Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana 2. SHREWS (Family Soricidae) Long-tailed Shrews Genus Sorex Arboreal Brown-toothed Shrew Episoriculus macrurus North American Least Shrew Cryptotis parva Old World Water Shrews Genus Neomys Ussuri White-toothed Shrew Crocidura lasiura Greater White-toothed Shrew Crocidura russula Siberian Shrew Crocidura sibirica Piebald Shrew Diplomesodon pulchellum 3. -

Fowlers Gap Biodiversity Checklist Reptiles

Fowlers Gap Biodiversity Checklist ow if there are so many lizards then they should make tasty N meals for someone. Many of the lizard-eaters come from their Reptiles own kind, especially the snake-like legless lizards and the snakes themselves. The former are completely harmless to people but the latter should be left alone and assumed to be venomous. Even so it odern reptiles are at the most diverse in the tropics and the is quite safe to watch a snake from a distance but some like the Md rylands of the world. The Australian arid zone has some of the Mulga Snake can be curious and this could get a little most diverse reptile communities found anywhere. In and around a disconcerting! single tussock of spinifex in the western deserts you could find 18 species of lizards. Fowlers Gap does not have any spinifex but even he most common lizards that you will encounter are the large so you do not have to go far to see reptiles in the warmer weather. Tand ubiquitous Shingleback and Central Bearded Dragon. The diversity here is as astonishing as anywhere. Imagine finding six They both have a tendency to use roads for passage, warming up or species of geckos ranging from 50-85 mm long, all within the same for display. So please slow your vehicle down and then take evasive genus. Or think about a similar diversity of striped skinks from 45-75 action to spare them from becoming a road casualty. The mm long! How do all these lizards make a living in such a dry and Shingleback is often seen alone but actually is monogamous and seemingly unproductive landscape? pairs for life. -

Spatial Ecology of the Oregon Gartersnake, Thamnophis Atratus Hydrophilus, in a Free-Flowing Stream Environment

Copeia 2010, No. 1, 75–85 Spatial Ecology of the Oregon Gartersnake, Thamnophis atratus hydrophilus, in a Free-Flowing Stream Environment Hartwell H. Welsh, Jr.1, Clara A. Wheeler1, and Amy J. Lind2 Spatial patterns of animals have important implications for population dynamics and can reveal other key aspects of a species’ ecology. Movements and the resulting spatial arrangements have fitness and genetic consequences for both individuals and populations. We studied the spatial and dispersal patterns of the Oregon Gartersnake, Thamnophis atratus hydrophilus, using capture–recapture techniques. Snakes showed aggregated dispersion. Frequency distributions of movement distances were leptokurtic; the degree of kurtosis was highest for juvenile males and lowest for adult females. Males were more frequently recaptured at locations different from their initial capture sites, regardless of age class. Dispersal of neonates was not biased, whereas juvenile and adult dispersal were male-biased, indicating that the mechanisms that motivate individual movements differed by both age class and sex. Males were recaptured within shorter time intervals than females, and juveniles were recaptured within shorter time intervals than adults. We attribute differences in capture intervals to higher detectability of males and juveniles, a likely consequence of their greater mobility. The aggregated dispersion appears to be the result of multi-scale habitat selection, and is consistent with the prey choices and related foraging strategies exhibited by the different age classes. Inbreeding avoidance in juveniles and mate-searching behavior in adults may explain the observed male-biased dispersal patterns. ULTIPLE interacting factors may affect the resources such as food, basking sites, hibernacula or mates movements and resulting spatial patterns of (Gregory et al., 1987). -

Berriquin LWMP Wildlife

Berriquin Wildlife Murray Land & Water Management Plan Wildlife Survey 2005-2006 Matthew Herring David Webb Michael Pisasale INTRODUCTION Why do a wildlife survey? 106 farms and were surveyed One of the great things about between June 2005 and March living in rural Australia is all the 2006. They incorporated a range wildlife that we share the land- of vegetation types (e.g. Black scape with. Historically, humans Box Woodland) as well as reveg- have impacted on the survival of etation on previously cleared many native plants and animals. land and constructed wetlands. Fortunately, there is a grow- Methods used to survey wildlife ing commitment in the country included: to wildlife conservation on the farm. As we improve our knowl- - Bird surveys edge and understanding of the - Log rolling for reptiles and local landscape and the animals frogs and plants that live in it we will - Spotlighting for mammals, rep be in a much better position to tiles and nocturnal birds conserve and enhance our natu- - Elliot traps for small mammals ral heritage for future genera- and reptiles tions. - Pitfall trapping for reptiles and frogs This wildlife survey was an ini- - Harp traps for bats tiative of the Berriquin Land & - Using the “Anabat” to record Water Management Plan (LWMP) bat calls M.Herring Working Group and is the largest - Call broadcasting to attract Wildlife expert Adam Bester and most extensive ever un- birds with 11 Little Forest Bats, one dertaken in the area. Berriquin of Berriquin’s most abundant was one of four LWMP areas that Other targeted methods were mammals. -

Action Statement Floraflora and and Fauna Fauna Guarantee Guarantee Act Act 1988 1988 No

Action Statement FloraFlora and and Fauna Fauna Guarantee Guarantee Act Act 1988 1988 No. No. ### 108 Hooded Scaly-foot Pygopus nigriceps Description and Distribution The Hooded Scaly-foot Pygopus nigriceps belongs to the reptile family Pygopodidae, the legless or flap-footed lizards. Legless lizards are superficially snake-like; they lack forelimbs, and the hind limbs are reduced to a scaly flap just above the vent. Whilst their eyes are lidless and snake-like, there are several features that distinguish legless lizards from snakes. Most legless lizards have an obvious ear aperture, lacking in all snakes, and a broad fleshy tongue, compared to the deeply forked tongue of snakes. Most legless lizards also have a tail that, when unbroken, is considerably longer than their body. In contrast, the tail of snakes is considerably Hooded Scaly-foot, Pygopus nigriceps shorter than their body. The genus Pygopus Illustration by Peter Robertson Wildlife Profiles P/L © differs from other legless lizards on the basis of the combination of the following features: head covered with enlarged, symmetrical scales; smooth (compared to keeled) ventral scales; and the possession of eight or more preanal pores. Two species of Pygopus occur in Victoria. The Hooded Scaly-foot is a large legless lizard, attaining a total length of 475mm, and a snout- vent length of about 180mm. Females reach larger sizes than males. Variable in colour, the Hooded Scaly-foot may be pale grey to reddish-brown on the dorsal surface and whitish on the ventral surface. The dorsal scales may be dark-edged, forming a reticulated pattern, or individual pale and dark scales may form a vague longitudinal pattern. -

Phylogenetic Relationships of Terrestrial Australo-Papuan Elapid Snakes (Subfamily Hydrophiinae) Based on Cytochrome B and 16S Rrna Sequences J

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Vol. 10, No. 1, August, pp. 67–81, 1998 ARTICLE NO. FY970471 Phylogenetic Relationships of Terrestrial Australo-Papuan Elapid Snakes (Subfamily Hydrophiinae) Based on Cytochrome b and 16S rRNA Sequences J. Scott Keogh,*,†,1 Richard Shine,* and Steve Donnellan† *School of Biological Sciences A08, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales 2006, Australia; and †Evolutionary Biology Unit, South Australian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia 5000, Australia Received April 24, 1997; revised September 4, 1997 quence data support many of the conclusions reached Phylogenetic relationships among the venomous Aus- by earlier studies using other types of data, but addi- tralo-Papuan elapid snake radiation remain poorly tional information will be needed before the phylog- resolved, despite the application of diverse data sets. eny of the Australian elapids can be fully resolved. To examine phylogenetic relationships among this 1998 Academic Press enigmatic group, portions of the cytochrome b and 16S Key Words: mitochondrial DNA; cytochrome b; 16S rRNA mitochondrial DNA genes were sequenced from rRNA; reptile; snake; elapid; sea snake; Australia; New 19 of the 20 terrestrial Australian genera and 6 of the 7 Guinea; Pacific; Asia; biogeography. terrestrial Melanesian genera, plus a sea krait (Lati- cauda) and a true sea snake (Hydrelaps). These data clarify several significant issues in elapid phylogeny. First, Melanesian elapids form sister groups to Austra- INTRODUCTION lian species, indicating that the ancestors of the Austra- lian radiation came via Asia, rather than representing The diverse, cosmopolitan, and medically important a relict Gondwanan radiation. Second, the two major elapid snakes are a monophyletic clade of approxi- groups of sea snakes (sea kraits and true sea snakes) mately 300 species and 61 genera (Golay et al., 1993) represent independent invasions of the marine envi- primarily defined by their unique venom delivery sys- ronment. -

An Investigation of the Evolution of Australian Elapid Snake Venoms

toxins Article Rapid Radiations and the Race to Redundancy: An Investigation of the Evolution of Australian Elapid Snake Venoms Timothy N. W. Jackson 1, Ivan Koludarov 1, Syed A. Ali 1,2, James Dobson 1, Christina N. Zdenek 1, Daniel Dashevsky 1, Bianca op den Brouw 1, Paul P. Masci 3, Amanda Nouwens 4, Peter Josh 4, Jonathan Goldenberg 1, Vittoria Cipriani 1, Chris Hay 1, Iwan Hendrikx 1, Nathan Dunstan 5, Luke Allen 5 and Bryan G. Fry 1,* 1 Venom Evolution Lab, School of Biological Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia; [email protected] (T.N.W.J.); [email protected] (I.K.); [email protected] (S.A.A.); [email protected] (J.D.); [email protected] (C.N.Z.); [email protected] (D.D.); [email protected] (B.o.d.B.); [email protected] (J.G.); [email protected] (V.C.); [email protected] (C.H.); [email protected] (I.H.) 2 HEJ Research Institute of Chemistry, International Centre for Chemical and Biological Sciences (ICCBS), University of Karachi, Karachi 75270, Pakistan 3 Princess Alexandra Hospital, Translational Research Institute, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia; [email protected] 4 School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia; [email protected] (A.N.); [email protected] (P.J.) 5 Venom Supplies, Tanunda, South Australia 5352, Australia; [email protected] (N.D.); [email protected] (L.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-4-0019-3182 Academic Editor: Nicholas R. -

Recent Taxonomic Changes and Additions to the Snake Fauna of New

21 assessments had been undertaken that did Recent taxonomic changes and additions not result in an application for an agreement or to the snake fauna of New South Wales a statement. 24 assessments were currently being Steve Sass1,2 undertaken, of which: 1EnviroKey, PO Box 7231, Tathra NSW 2550 5 would definitely result in an application 2Ecology & Biodiversity Group, Charles Sturt University, 9 would definitely not result in an application Thurgoona, NSW 2541 10 were undecided/not sure [email protected] To a significant degree, the future of the BioBanking program is in our hands. As Assessors, it is our role to Since the ‘Complete Guide to the Reptiles of introduce the idea to our clients and sell the concept. Australia‛ was first published in 2003, more than 80 No matter how cynical you might be about the reptile species have been added to the list of described modelling, the data upon which it is built, access to reptile species in Australia, bringing the total number the program, the cost of training or the unusual to 923 in the third and most recent addition (Wilson application of the program in part of western Sydney: and Swan 2010). These additions being the result of you must admit that it provides a mechanism to get newly discovered species, naming of previously important privately-owned pieces of country into a undescribed species, and taxonomic reviews of perpetual reserve network. If it is not achieving that, various species and genera. This has resulted in then it is partly our fault and we need to work at it. -

A Preliminary Risk Assessment of Cane Toads in Kakadu National Park Scientist Report 164, Supervising Scientist, Darwin NT

supervising scientist 164 report A preliminary risk assessment of cane toads in Kakadu National Park RA van Dam, DJ Walden & GW Begg supervising scientist national centre for tropical wetland research This report has been prepared by staff of the Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist (eriss) as part of our commitment to the National Centre for Tropical Wetland Research Rick A van Dam Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist, Locked Bag 2, Jabiru NT 0886, Australia (Present address: Sinclair Knight Merz, 100 Christie St, St Leonards NSW 2065, Australia) David J Walden Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist, GPO Box 461, Darwin NT 0801, Australia George W Begg Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist, GPO Box 461, Darwin NT 0801, Australia This report should be cited as follows: van Dam RA, Walden DJ & Begg GW 2002 A preliminary risk assessment of cane toads in Kakadu National Park Scientist Report 164, Supervising Scientist, Darwin NT The Supervising Scientist is part of Environment Australia, the environmental program of the Commonwealth Department of Environment and Heritage © Commonwealth of Australia 2002 Supervising Scientist Environment Australia GPO Box 461, Darwin NT 0801 Australia ISSN 1325-1554 ISBN 0 642 24370 0 This work is copyright Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Supervising Scientist Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction -

Brigalow Belt Bioregion – a Biodiversity Jewel

Brigalow Belt bioregion – a biodiversity jewel Brigalow habitat © Craig Eddie What is brigalow? including eucalypt and cypress pine forests and The term ‘brigalow’ is used simultaneously to refer to; woodlands, grasslands and other Acacia dominated the tree Acacia harpophylla; an ecological community ecosystems. dominated by this tree and often found in conjunction with other species such as belah, wilga and false Along the eastern boundary of the Brigalow Belt are sandalwood; and a broader region where this species scattered patches of semi-evergreen vine thickets with and ecological community are present. bright green canopy species that are highly visible among the more silvery brigalow communities. These The Brigalow Belt bioregion patches are a dry adapted form of rainforest, relics of a much wetter past. The Brigalow Belt bioregion is a large and complex area covering 36,400 000ha. The region is thus recognised What are the issues? by the Australian Government as a biodiversity hotspot. Nature conservation in the region has received increasing attention because of the rapid and extensive This hotspot contains some of the most threatened loss of habitat that has occurred. Since World War wildlife in the world, including populations of the II the Brigalow Belt bioregion has become a major endangered bridled nail-tail wallaby and the only agricultural and pastoral area. Broad-scale clearing for remaining wild population of the endangered northern agriculture and unsustainable grazing has fragmented hairy-nosed wombat. The area contains important the original vegetation in the past, particularly on habitat for rare and threatened species including the, lowland areas. glossy black-cockatoo, bulloak jewel butterfl y, brigalow scaly-foot, red goshawk, little pied bat, golden-tailed geckos and threatened community of semi evergreen Biodiversity hotspots are areas that support vine thickets. -

Report-Mungo National Park-Appendix A

Mungo National Park, NSW, 2017 Appendix A: Fauna species lists Family Species Common name Reptiles Agamidae Ctenophorus fordi Mallee Military Dragon Agamidae Ctenophorus pictus Painted Dragon Agamidae Diporiphora nobbi Nobbi Dragon Agamidae Pogona vitticeps Central Bearded Dragon Agamidae Tympanocryptis lineata Lined Earless Dragon Agamidae Tympanocryptis tetraporophora Eyrean Earless Dragon Carphodactylidae Nephrurus levis Smooth Knob-tailed Gecko Carphodactylidae Underwoodisaurus milii Thick-tailed Gecko Diplodactylidae Diplodactylus furcosus Ranges Stone Gecko Diplodactylidae Diplodactylus tessellatus Tessellated Gecko Diplodactylidae Diplodactylus vittatus Eastern Stone Gecko Diplodactylidae Lucasium damaeum Beaded Gecko Diplodactylidae Rhynchoedura ormsbyi Eastern Beaked Gecko Diplodactylidae Strophurus elderi ~ Jewelled Gecko Diplodactylidae Strophurus intermedius Southern Spiny-tailed Gecko Elapidae Brachyurophis australis Australian Coral Snake Elapidae Demansia psammophis Yellow-faced Whip Snake Elapidae Parasuta nigriceps Mallee Black-headed Snake Elapidae Pseudechis australis Mulga Snake Elapidae Pseudonaja aspidorhyncha * Strap-snouted Brown Snake Elapidae Pseudonaja textilis Eastern Brown Snake Elapidae Suta suta Curl Snake Gekkonidae Gehyra versicolor Eastern Tree Gecko Gekkonidae Heteronotia binoei Bynoe's Gecko Pygopodidae Delma butleri Butler's Delma Pygopodidae Lialis burtonis Burton's Legless Lizard Pygopodidae Pygopus schraderi Eastern Hooded Scaly-foot Scincidae Cryptoblepharus australis Inland Snake-eyed Skink Scincidae