Violent Content in Film: a Defense of the Morally Shocking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religion, Homosexuality, and Collisions of Liberty and Equality in American Public Law

A Jurisprudence of "Coming Out": Religion, Homosexuality, and Collisions of Liberty and Equality in American Public Law William N. Eskridge, Jr.! Conflicts among religious and ethnic groups have scored American cultural and political history. Some of these conflicts have involved campaigns of suppression against deviant religious and minority ethnic groups by the mainstream. Although the law has most often been deployed as an instrument of suppression, there is now a public law consensus to preserve and protect the autonomy of religious and ethnic subcultures, as well as the ability of their members to self-identify without penalty. One thesis of this Essay is that this vaunted public law consensus should be extended to sexual orientation minorities as well. Like religion, sexual orientation marks both personal identity and social divisions.' In this century, in fact, sexual orientation has steadily been replacing religion as the identity characteristic that is both physically invisible and morally polarizing. In 1900, one's group identity was largely defined by one's ethnicity, social class, sex, and religion. The norm was Anglo-Saxon, middle-class, male, and Protestant. The Jew, Roman Catholic, or Jehovah's Witness was considered deviant and was subject to social, economic, and political discrimination. In 2000, one's group identity will be largely defined by one's race, income, sex, and sexual orientation. The norm will be white, middle-income, male, and heterosexual. The lesbian, gay man, or transgendered person will be considered deviant and will be subject to social, economic, and political discrimination. t Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center. An earlier draft of this Essay was presented at workshops held at the Georgetown University Law Center. -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

The 007Th Minute Ebook Edition

“What a load of crap. Next time, mate, keep your drug tripping private.” JACQUES A person on Facebook. STEWART “What utter drivel” Another person on Facebook. “I may be in the minority here, but I find these editorial pieces to be completely unreadable garbage.” Guess where that one came from. “No, you’re not. Honestly, I think of this the same Bond thinks of his obituary by M.” Chap above’s made a chum. This might be what Facebook is for. That’s rather lovely. Isn’t the internet super? “I don’t get it either and I don’t have the guts to say it because I fear their rhetoric or they’d might just ignore me. After reading one of these I feel like I’ve walked in on a Specter round table meeting of which I do not belong. I suppose I’m less a Bond fan because I haven’t read all the novels. I just figured these were for the fans who’ve read all the novels including the continuation ones, fan’s of literary Bond instead of the films. They leave me wondering if I can even read or if I even have a grasp of the language itself.” No comment. This ebook is not for sale but only available as a free download at Commanderbond.net. If you downloaded this ebook and want to give something in return, please make a donation to UNICEF, or any other cause of your personal choice. BOOK Trespassers will be masticated. Fnarr. BOOK a commanderbond.net ebook COMMANDERBOND.NET BROUGHT TO YOU BY COMMANDERBOND.NET a commanderbond.net book Jacques I. -

Music and Migratory Subjects in Pedro Almodóvar's <Em>Todo Sobre Mi

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Modern Languages and Literatures Faculty Research Modern Languages and Literatures Department Spring 2014 Music and Migratory Subjects in Pedro Almodóvar’s Todo Sobre Mi Madre, Hable con Ella, and Volver Debra J. Ochoa Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/mll_faculty Part of the Modern Languages Commons Repository Citation Ochoa, D.J. (2014). Music and migratory subjects in Almodóvar's todo sobre mi madre, hable con ella, and volver. Confluencia, 29(2), 129-141. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Modern Languages and Literatures Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Languages and Literatures Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Music and Migratory Subjects in Almodóvar's Todo sobre mi madre. Hable con ella, and Volver Veí^íiJ. Ock&ti Trinity University Since the end of Erancisco Franco's dictatorship (1939-1975), Spain has transformed itself from an isolated, fascist state dominated by the promotion of hispanidad and national Catholicism (Corkill 49) to a country that hosts nearly 5.7 million international residents (Deveny, Migration 4). Pedro Almodovar, who began his film career at the time of Spain's transition to democracy, has steadily responded to the country's changes through his examination of identity, sexuality, repression, and desire (Acevedo-Muñoz 1—2). The director has distinguished himself partly by his continuous use of international music in his films, in a way that corresponds to Spain's development into a more tolerant, liberal, multicultural state (Kinder, "Pleasure" 37). -

Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society

Capri Community Film Society Papers Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society Auburn University at Montgomery Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library Written By: Rickey Best & Jason Kneip Last Updated: 2/19/2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2-3 Index Terms 3 Agency History 3-4 1 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Scope and Content 5 Arrangement 5-10 Inventory 10- Collection Summary Creator: Capri Community Film Society Title: Capri Community Film Society Papers Dates: 1983-present Quantity: 6 boxes; 6.0 cu. Ft. Identification: 92/2 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Capri Community Film Society Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: The collection began with an initial transfer on September 19, 1991. A second donation occurred in February, 1995. Since then, regular donations of papers occur on a yearly basis. Processed By: Jermaine Carstarphen, Student Assistant & Rickey Best, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1993); Jason Kneip, Archives/Special Collections Librarian. Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant. 2 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Restrictions Restrictions on access: Access to membership files is closed for 25 years from date of donation. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. Index Terms The material is indexed under the following headings in the Auburn University at Montgomery’s Library catalogs – online and offline. -

Understanding a Serbian Film: the Effects of Censorship and File- Sharing on Critical Reception and Perceptions of Serbian National Identity in the UK Kapka, A

Understanding A Serbian Film: The Effects of Censorship and File- sharing on Critical Reception and Perceptions of Serbian National Identity in the UK Kapka, A. (2014). Understanding A Serbian Film: The Effects of Censorship and File-sharing on Critical Reception and Perceptions of Serbian National Identity in the UK. Frames Cinema Journal, (6). http://framescinemajournal.com/article/understanding-a-serbian-film-the-effects-of-censorship-and-file-sharing- on-critical-reception-and-perceptions-of-serbian-national-identity-in-the-uk/ Published in: Frames Cinema Journal Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2017 University of St Andrews and contributers.This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. -

A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2015 Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices Sultana Aaliuah Shabazz University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Shabazz, Sultana Aaliuah, "Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2015. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3607 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Sultana Aaliuah Shabazz entitled "Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Education. Barbara J. Thayer-Bacon, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Harry Dahms, Rebecca Klenk, Lois Presser Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

To View Online Click Here

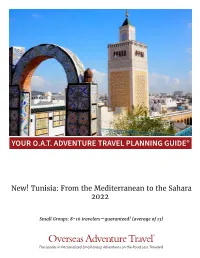

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® New! Tunisia: From the Mediterranean to the Sahara 2022 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. New! Tunisia: From the Mediterranean to the Sahara itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: Venture out to the Tataouine villages of Chenini and Ksar Hedada. In Chenini, your small group will interact with locals and explore the series of rock and mud-brick houses that are seemingly etched into the honey-hued hills. After sitting down for lunch in a local restaurant, you’ll experience Ksar Hedada, where you’ll continue your people-to-people discoveries as you visit a local market and meet local residents. You’ll also meet with a local activist at a coffee shop in Tunis’ main medina to discuss social issues facing their community. You’ll get a personal perspective on these issues that only a local can offer. The way we see it, you’ve come a long way to experience the true culture—not some fairytale version of it. So we keep our groups small, with only 8-16 travelers (average 13) to ensure that your encounters with local people are as intimate and authentic as possible. -

Negotiating the Non-Narrative, Aesthetic and Erotic in New Extreme Gore

NEGOTIATING THE NON-NARRATIVE, AESTHETIC AND EROTIC IN NEW EXTREME GORE. A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication, Culture, and Technology By Colva Weissenstein, B.A. Washington, DC April 18, 2011 Copyright 2011 by Colva Weissenstein All Rights Reserved ii NEGOTIATING THE NON-NARRATIVE, AESTHETIC AND EROTIC IN NEW EXTREME GORE. Colva O. Weissenstein, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Garrison LeMasters, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This thesis is about the economic and aesthetic elements of New Extreme Gore films produced in the 2000s. The thesis seeks to evaluate film in terms of its aesthetic project rather than a traditional reading of horror as a cathartic genre. The aesthetic project of these films manifests in terms of an erotic and visually constructed affective experience. It examines the films from a thick descriptive and scene analysis methodology in order to express the aesthetic over narrative elements of the films. The thesis is organized in terms of the economic location of the New Extreme Gore films in terms of the film industry at large. It then negotiates a move to define and analyze the aesthetic and stylistic elements of the images of bodily destruction and gore present in these productions. Finally, to consider the erotic manifestations of New Extreme Gore it explores the relationship between the real and the artificial in horror and hardcore pornography. New Extreme Gore operates in terms of a kind of aesthetic, gore-driven pornography. Further, the films in question are inherently tied to their economic circumstances as a result of the significant visual effects technology and the unstable financial success of hyper- violent films. -

M Usic , M Oviesand M

Nov.Nov. 3,3, 20052005 Music,M u s i c , MMovieso v i e s anda n d MoreM o r e ‘Saw II’ rips through theaters MUSIC: Neil YYoungoung, GZA and AAshleeshlee Simpson brbringing new music ttoo fanfanss MOVIE: ‘L‘Legendegend of ZZorro’orro’ makes marmark,k, ‘Nor‘Northth CCountry’ountry’ ttouchesouches audiencaudienceses MORE: RReadead fforor yyourour ststomach,omach, plus the lalatesttest enentertainmenttertainment newnewss 2 THE BUZZ the cover of the December-Janu- ary 2006 … Barbara Walters will Contents ary issue of Teen People. Jessica be presenting her “10 Most Fasci- Simpson, 25, a self-proclaimed nating People of 2005.” Some of THE ditz, tells the magazine she went to the infl uential people who made The Inside Buzz therapy during her publicity over- the cut include Kanye West, Sec- 02 I N S I D E load; sister Ashlee opens up about retary of State Condoleezza Rice her recent singing fl ops, like the and even Tom Mesereau, Michael 03 Girls That Rock Series - Part 3 infamous “Saturday Night Live” Jackson’s lawyer. The show will BUZZ lip-synching debacle and the Or- air on Nov. 29 on ABC at 10 p.m. ange Bowl fi asco … 33-year-old … Notable CD releases out Tues- 04 New Movie Reviews actress Gabrielle Union has sepa- day were Santana All That I Am rated from husband, Chris How- … Rammstein Rosenrot [Import] 05 New Movie Reviews ard, a former Jacksonville Jaguar … John Fogerty The Long Road running back. … Mary J. Blige Home: Ultimate John Fogerty 06 Flashback Favorite will receive the VLegend Award Creedence Collection … new By MAHSA KHALILIFAR from Vibe at the 3rd annual awards DVD releases this week include Daily Titan Asst. -

Spy Films, American Foreign Policy, and the New Frontier of the 1960S

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses Spring 2019 Bondmania: Spy Films, American Foreign Policy, and the New Frontier of the 1960s Luke Pearsons Central Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, History of Gender Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Pearsons, Luke, "Bondmania: Spy Films, American Foreign Policy, and the New Frontier of the 1960s" (2019). All Master's Theses. 1202. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/1202 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BONDMANIA: SPY FILMS, AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY, AND THE NEW FRONTIER OF THE 1960s __________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty Central Washington University ___________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts History ___________________________________ by Luke Thomas Pearsons May 2019 CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies We hereby approve the thesis of Luke Thomas Pearsons Candidate for the degree of Master of Arts APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Stephen Moore, Committee Chair ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Daniel Herman ______________ _________________________________________ Dr. Chong Eun Ahn ______________ _________________________________________ Dean of Graduate Studies ii ABSTRACT BONDMANIA: SPY FILMS, AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY, AND THE NEW FRONTIER OF THE 1960s by Luke Thomas Pearsons May 2019 The topic of this thesis are spy films that were produced during the Cold War, with a specific focus on the James Bond films and their numerous imitators. -

DVD Profiler

101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London Adventure Animation Family Comedy2003 74 minG Coll.# 1 C Barry Bostwick, Jason Alexander, The endearing tale of Disney's animated classic '101 Dalmatians' continues in the delightful, all-new movie, '101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London A Martin Short, Bobby Lockwood, Adventure'. It's a fun-filled adventure fresh with irresistible original music and loveable new characters, voiced by Jason Alexander, Martin Short and S Susan Blakeslee, Samuel West, Barry Bostwick. Maurice LaMarche, Jeff Bennett, T D.Jim Kammerud P. Carolyn Bates C. W. Garrett K. SchiffM. Geoff Foster 102 Dalmatians Family 2000 100 min G Coll.# 2 C Eric Idle, Glenn Close, Gerard Get ready for outrageous fun in Disney's '102 Dalmatians'. It's a brand-new, hilarious adventure, starring the audacious Oddball, the spotless A Depardieu, Ioan Gruffudd, Alice Dalmatian puppy on a search for her rightful spots, and Waddlesworth, the wisecracking, delusional macaw who thinks he's a Rottweiler. Barking S Evans, Tim McInnerny, Ben mad, this unlikely duo leads a posse of puppies on a mission to outfox the wildly wicked, ever-scheming Cruella De Vil. Filled with chases, close Crompton, Carol MacReady, Ian calls, hilarious antics and thrilling escapes all the way from London through the streets of Paris - and a Parisian bakery - this adventure-packed tale T D.Kevin Lima P. Edward S. Feldman C. Adrian BiddleW. Dodie SmithM. David Newman 16 Blocks: Widescreen Edition Action Suspense/Thriller Drama 2005 102 min PG-13 Coll.# 390 C Bruce Willis, Mos Def, David From 'Lethal Weapon' director Richard Donner comes "a hard-to-beat thriller" (Gene Shalit, 'Today'/NBC-TV).