Origin and Evolution of Double Entry Bookkeeping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Ledger Budgeting User Guide

General Ledger Budgeting User Guide Version 9.0 February 2006 Document Number FBUG-90UW-01 Lawson Enterprise Financial Management Legal Notices Lawson® does not warrant the content of this document or the results of its use. Lawson may change this document without notice. Export Notice: Pursuant to your agreement with Lawson, you are required (at your own expense) to comply with all laws, rules, regulations, and lawful orders of any governmental body that apply to you and the products, services or information provided to you by Lawson. This obligation includes, without limitation, compliance with the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (which prohibits certain payments to governmental ofÞcials and political parties), U.S. export control regulations, and U.S. regulations of international boycotts. Without limiting the foregoing, you may not use, distribute or export the products, services or information provided to you by Lawson except as permitted by your agreement with Lawson and any applicable laws, rules, regulations or orders. Non-compliance with any such law, rule, regulation or order shall constitute a material breach of your agreement with Lawson. Trademark and Copyright Notices: All brand or product names mentioned herein are trademarks or registered trademarks of Lawson, or the respective trademark owners. Lawson customers or authorized Lawson business partners may copy or transmit this document for their internal use only. Any other use or transmission requires advance written approval of Lawson. © Copyright 2006 Lawson Software, Inc. All rights reserved. Contents List of Figures 7 Chapter 1 Overview of Budgeting 9 Budgeting ProcessFlow...............................................................9 HowBudgeting Integrates WithOtherLawsonApplications..................... 11 What is a Budget?................................................................... -

History of Accounting Development

Journal of History Culture and Art Research (ISSN: 2147-0626) Tarih Kültür ve Sanat Araştırmaları Dergisi Vol. 6, No. 4, September 2017 Revue des Recherches en Histoire Culture et Art Copyright © Karabuk University http://kutaksam.karabuk.edu.tr ﻣﺠﻠﺔ ﺍﻟﺒﺤﻮﺙ ﺍﻟﺘﺎﺭﻳﺨﻴﺔ ﻭﺍﻟﺜﻘﺎﻓﻴﺔ ﻭﺍﻟﻔﻨﻴﺔ DOI: 10.7596/taksad.v6i4.1163 Citation: Mukhametzyanov, R., Nugaev, F., & Muhametzyanova, L. (2017). History of Accounting Development. Journal of History Culture and Art Research, 6(4), 1227-1236. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.7596/taksad.v6i4.1163 History of Accounting Development Rinaz Z. Mukhametzyanov1, Fatih Sh. Nugaev2 Lyaisan Z. Muhametzyanova3 Abstract Everyone is well aware that accounting is one of the most important areas of economy, which has become so widespread in our lives today that it is impossible to imagine modern business and economy without this component. Accounting is a well thought out system that reflects the movement of various facts of economic life, no matter how different they are, and leads them into a common logical system. We can talk a lot about the features and possibilities of this science, but how often do we think about the ways this system arose, the ways of its development and becoming a separate science? During the study of this problem, an attempt was made to systematize various points of view regarding the origin and the development of accounting. After the result of the analysis, the authors identified regularities in the development of accounting and its methodical apparatus associated with the periodization of history on technological structures. Keywords: History of accounting development, Sources of accounting, Accounting, Techno- economic paradigm. -

A73 Cash Basis Accounting

World A73 Cash Basis Accounting Net Change with new Cash Basis Accounting program: The following table lists the enhancements that have been made to the Cash Basis Accounting program as of A7.3 cum 15 and A8.1 cum 6. CHANGE EXPLANATION AND BENEFIT Batch Type Previously cash basis batches were assigned a batch type of ‘G’. Now cash basis batches have a batch type of ‘CB’, making it easier to distinguish cash basis batches from general ledger batches. Batch Creation Previously, if creating cash basis entries for all eligible transactions, all cash basis entries would be created in one batch. Now cash basis entries will be in separate batches based on a one-to-one batch ratio with the originating AA ledger batch. For example, if cash basis entries were created from 5 separate AA ledger batches, there will be 5 resulting AZ ledger batches. This will make it simpler to track posting issues as well as alleviate problems inquiring on cash basis entries where there were potential duplicate document numbers/types within the same batch. Batch Number Previously cash basis batch numbers were unique in relation to the AA ledger batch that corresponded to the cash basis entries. Now the cash basis batch number will match the original AA ledger batch, making it easier to track and audit cash basis entries in relation to the originating transactions. Credit Note Prior to A7.3 cum 14/A8.1 cum 4, the option to assign a document type Reimbursement other than PA to the voucher generated for reimbursement did not exist. -

ACCOUNTING and AUDITING in ROMAN SOCIETY Lance Elliot

ACCOUNTING AND AUDITING IN ROMAN SOCIETY Lance Elliot LaGroue A dissertation thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: Richard Talbert Fred Naiden Howard Aldrich Terrence McIntosh © 2014 Lance Elliot LaGroue ALL RIGHTS RESERVED II ABSTRACT Lance LaGroue: Accounting and Auditing in Roman Society (Under the direction of Richard Talbert) This dissertation approaches its topic from the pathbreaking dual perspective of a historian and of an accountant. It contributes to our understanding of Roman accounting in several notable ways. The style and approach of Roman documents are now categorized to reflect differing levels of complexity and sophistication. With the aid of this delineation, and by comparison with the practices of various other premodern societies, we can now more readily appreciate the distinct attributes present at each level in Roman accounting practices. Additionally, due to the greater accessibility of Roman accounting documents in recent years – in particular, through John Matthews’ work on the Journey of Theophanes, Dominic Rathbone’s study of the Heroninos archive, and the reading of the Vindolanda tablets -- it becomes easier to appreciate such differences among the few larger caches of accounting documents. Moreover, the dissertation seeks to distinguish varying grades of accountant. Above all, it emphasizes the need to separate the functions of accounting and auditing, and to gauge the essential characteristics and roles of both. In both regards, it is claimed, the Roman method showed competency. The dissertation further shows how economic and accounting theory has influenced perceptions about Roman accounting practices. -

Oracle General Ledger

ORACLE DATA SHEET ORACLE GENERAL LEDGER KEY FEATURES Oracle® General Ledger is a comprehensive financial management • Flexible chart of accounts and reporting structures solution that provides highly automated financial processing, • Centralized setup for fast effective management control, and real-time visibility to financial implementations • Simultaneous accounting for results. It provides everything you need to meet financial multiple reporting requirements compliance and improve your bottom line. Oracle General Ledger • Compliance with multiple is part of the Oracle E-Business Suite, an integrated suite of legislative, industry or geographic requirements applications that drive enterprise profitability, reduce costs, • Spreadsheet integration for improve internal controls and increase efficiency. journals, budgets, reporting, and currency rates • Tight internal controls and Capitalize on Global Opportunities access to legal entity and ledger data Meet Varied Reporting Standards with a Flexible Accounting Model • Multi-ledger financial reporting for real-time, In today’s complex, global, and regulated environment, finance organizations face enterprise-wide visibility challenges in trying to comply with local regulations and multiple reporting • Robust drilldowns to underlying transactions requirements. Oracle General Ledger allows companies to meet these challenges in • Professional quality reporting a very streamlined and automated fashion. Multiple ledgers can be assigned to a • One-touch multi-ledger legal entity to meet statutory, corporate, regulatory, and management reporting. All processing accounting representations can be simultaneously maintained for a single • Automated month-end close processing transaction. For example, a single journal entered in the main, record-keeping • Fastest and most scalable ledger can be automatically represented in multiple ledgers even if each ledger uses general ledger on the market a different chart of accounts, calendar, currency, and accounting principle. -

1 the Genesis of Double Entry Bookkeeping Alan Sangster, Griffith University, Aust

The Genesis of Double Entry Bookkeeping Alan Sangster, Griffith University, Australia ABSTRACT This study investigates the emergence in Italy early in the 13th century, if not before, of a new form of single entry bookkeeping which, thereafter, gave rise to the variant form we know as double entry bookkeeping. In doing so, it considers both primary and secondary sources and the language of bookkeeping at that time, along with its suitability for the purpose to which it was being put; and compares the new form of single entry to that of double entry, pinpointing the single factor necessary to convert the former into the latter. Contrary to the findings of previous investigations and the assumptions made in the literature concerning its origins linked to trade, both of which indicate that double entry was an invention of merchants, this paper concludes that the most likely form of enterprise where bookkeeping of this form would have started is a bank. And, as the one form of business for which knowing your debtors and creditors is fundamental to survival, it is the obvious and by far the most likely activity from which detailed single and then double entry bookkeeping emerged. Key words: single entry bookkeeping; double entry bookkeeping; bank accounts; merchant accounts; medieval accounting practice. BACKGROUND This study was prompted by the recent publication of a best-selling book which has popularized the history of double entry bookkeeping (Gleeson-White, 2011). In its title – Double Entry: How the Merchants of Venice Shaped the Modern World and How their Invention could Make or Break the Planet – the author tells us that merchants invented double entry bookkeeping. -

General Ledger, Receivables Management, Payables Management, Sales Order Processing, Purchase Order Processing, and Invoicing

Chapter 11: Revenue/Expense Deferrals setup Before you begin using Revenue/Expense Deferrals, you need to set the options you want to use for creating deferral transactions, such as the posting method used, and user access options. This information includes the following sections: • Revenue/Expense Deferrals overview • Deferral posting methods • Balance Sheet posting example • Profit and Loss posting example • Setting up revenue/expense deferrals • Selecting deferral warning options • Setting up a deferral profile • Setting access to a deferral profile Revenue/Expense Deferrals overview Revenue/Expense Deferrals simplifies deferring revenues or distributing expenses over a specified period. Revenue or expense entries can be made to future periods automatically from General Ledger, Receivables Management, Payables Management, Sales Order Processing, Purchase Order Processing, and Invoicing. If you use deferral transactions frequently, you can set up deferral profiles, which are templates of commonly deferred transactions. Using deferral profiles helps ensure that similar transactions are entered with the correct information. For example, if you routinely enter transactions for service contracts your company offers, and the revenue is recognized over a 12-month period, you could set up a deferral profile for these service contracts, specifying the accounts to be used, and the method for calculating how the deferred revenue is recognized. Deferral posting methods You can use two methods for posting the initial transactions and the deferral transactions: the Balance Sheet method, and the Profit and Loss method. Balance Sheet Using the Balance Sheet method, you’ll identify two posting accounts: a Balance Sheet deferral account to be used with the initial transaction for the deferred revenue or expense, and a Profit and Loss recognition account to be used with each period’s deferral transaction that recognizes the expense or revenue. -

New Business Combinations Accounting Rules and the Mergers and Acquisitions Activity

NEW BUSINESS COMBINATIONS ACCOUNTING RULES AND THE MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS ACTIVITY HUMBERTO NUNO RITO RIBEIRO Doctor of Philosophy DE MONTFORT UNIVERSITY LEICESTER BUSINESS SCHOOL November 2009 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. Leicester Business School, De Montfort University New Business Combinations Accounting Rules and the Mergers and Acquisitions Activity Humberto Nuno Rito Ribeiro Doctor of Philosophy 2009 Thesis Summary The perennial controversy in business combinations accounting and its dialectic with stakeholders’ interests under the complexity of the Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) activity is the centrepiece of analysis in this thesis. It is argued here that the accounting regulation should be as neutral as possible for the economic activity, although it is recognised that accounting changes may result in economic effects. In the case of the changes for business combinations accounting in the USA, lobbying was so fierce that in order to achieve the abolition of accounting choice in M&A accounting, it forced the standard-setter to compromise and to change substantially some of its earlier proposals. Such fierce lobbying cast doubts about whether it was effectively possible to mitigate such economic effects, resulting in a possible impact of the accounting changes on the M&A activity. The occurrence of M&A in waves is yet to be fully theorised. Nevertheless, existing literature established relationships between M&A activity and some key economic and financial factors, and has provided several interesting theories and other meaningful contributions for this thesis. -

Accounting in Ancient Times: a Review of Classic References

Accounting in Ancient Times: A Review of Classic References (*) Assist. Prof. Dr. Roberta Provasi University of Milan, Italy Prof. Dr. Shawki Farag The American University in Cairo, Egypt Abstract European accounting scholars have made significant contributions to the history of accounting. Some of these contributions were not translated into English and as such were not integrated in the evolving comprehensive coverage of the evolution of the accounting function. The purpose of this research is to review the works of those scholars in the context of the ancient history of civilizations. The research starts with the oldest texts known which are dated to the end of the fourth millennium BC (3200-3100). These were sequences of pictographic signs, which represent the antecedents of the direct cuneiform writing, engraved on clay tablets found in the monumental temple district dell’Eanna of the city of Uruk, in southern Iraq. The content of these textsare of a primarily administrative: lists of goods in and out of rations distributed to employees, etc.. The writing is in response to the demands of an administrative system, developed in a centralized economy with strong redistributive character.It was governed by an elite priesthood, (*) Bu bildiri, 19-22 Haziran 2013 tarihlerinde İstanbul’da organize edilen III. Balkanlar ve Ortadoğu Ülkeleri Muhasebe ve Muhasebe Tarihi Konferansı’nda sunulmuştur. 68 which was formed in southern Mesopotamiaas a resultofthe so-called “urban revolution”. The system of signsengraved on the tablets (about 1200) was already fully formed, and, as such, has no direct antecedents. In a broader sense, however, it represents the end of a long process of developing accounting systems and management of there serves,the beginnings of which date back to Neolithic period and there for eat the time of the first agriculturel villages.This acounting systems prehistoric werw based essentially on two instruments:accounting tokens and theseals. -

A Centralized Ledger Database for Universal Audit and Verification

LedgerDB: A Centralized Ledger Database for Universal Audit and Verification Xinying Yangy, Yuan Zhangy, Sheng Wangx, Benquan Yuy, Feifei Lix, Yize Liy, Wenyuan Yany yAnt Financial Services Group xAlibaba Group fxinying.yang,yuenzhang.zy,sh.wang,benquan.ybq,lifeifei,yize.lyz,[email protected] ABSTRACT certain consensus protocol (e.g., PoW [32], PBFT [14], Hon- The emergence of Blockchain has attracted widespread at- eyBadgerBFT [28]). Decentralization is a fundamental basis tention. However, we observe that in practice, many ap- for blockchain systems, including both permissionless (e.g., plications on permissioned blockchains do not benefit from Bitcoin, Ethereum [21]) and permissioned (e.g., Hyperledger the decentralized architecture. When decentralized architec- Fabric [6], Corda [11], Quorum [31]) systems. ture is used but not required, system performance is often A permissionless blockchain usually offers its cryptocur- restricted, resulting in low throughput, high latency, and rency to incentivize participants, which benefits from the significant storage overhead. Hence, we propose LedgerDB decentralized ecosystem. However, in permissioned block- on Alibaba Cloud, which is a centralized ledger database chains, it has not been shown that the decentralized archi- with tamper-evidence and non-repudiation features similar tecture is indispensable, although they have been adopted to blockchain, and provides strong auditability. LedgerDB in many scenarios (such as IP protection, supply chain, and has much higher throughput compared to blockchains. It merchandise provenance). Interestingly, many applications offers stronger auditability by adopting a TSA two-way peg deploy all their blockchain nodes on a BaaS (Blockchain- protocol, which prevents malicious behaviors from both users as-a-Service) environment maintained by a single service and service providers. -

Ledger Entries – Overview

Ledger Entries – Overview Speech Cursor Actions The purpose of ledger entries is to record financial transactions as Slide: Ledger Entries produce a debits and credits, in a form appropriate to enter into your report of debits and credits, which accounting software. can be entered into your accounting software (e.g. Quickbooks, Simply Accounting) As Sumac users perform financially significant transactions – like Slide: As Sumac users enter receiving a donation, selling tickets, or renewing a membership – financial transactions, Sumac Sumac automatically breaks the components of the transactions creates Ledger Entries which into debits and credits and saves these into ledger entries. break the transactions into the appropriate debit and credit accounts. This approach separates accounting functions from other Slide: Ledger Entries let operational functions. It makes financial information available in bookkeepers reconcile financial a ledger format that is comfortable for bookkeeping and transactions between Sumac their accounting staff, but does not require everyone using Sumac to accounting software. become a bookkeeper. Ledger entries allocate funds to account codes, so the account Slide: Set up account codes in codes must be defined first. In Sumac, you need to define account Sumac to match the Chart of codes that correspond to accounts in the Chart of Accounts in your Accounts in your accounting accounting software. software. Ensure that each payment type is linked to the appropriate Slide: Set up account codes for account, since most receipts debit the payment type’s account each payment type. code. Make sure that each surcharge, like a sales tax, is linked to an Slide: Specify an account for each appropriate account, since surcharge amounts credit the surcharge. -

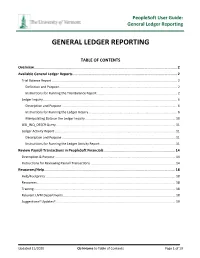

General Ledger Reporting

PeopleSoft User Guide: General Ledger Reporting GENERAL LEDGER REPORTING TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Available General Ledger Reports .................................................................................................... 2 Trial Balance Report ........................................................................................................................................... 2 Definition and Purpose ................................................................................................................................... 2 Instructions for Running the Trial Balance Report ......................................................................................... 2 Ledger Inquiry ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 Description and Purpose ................................................................................................................................ 6 Instructions for Running the Ledger Inquiry .................................................................................................. 6 Manipulating Data on the Ledger Inquiry .................................................................................................... 10 LED_INQ_DESCR Query ...................................................................................................................................