TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATIONS Volume 27, 2020, Number 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1.2019-12-25.UCD-Woo CV.Talks 16-18

25 December 2019 Curriculum Vitae Wing Thye Woo (胡永泰) Distinguished Professor Tel No: +1-530-752-3035 Department of Economics Fax No: +1-530-752-2625 University of California [email protected] One Shields Avenue Davis, California 95616 Research Interests: Economic Growth and Sustainable Development (especially in China, Indonesia, and Malaysia), Macroeconomics, Exchange Rate Economics, and Public Economics. Languages: Mandarin, Cantonese, Taiwanese, Bahasa Malaysia, Bahasa Indonesia Education Harvard University - Sept. 1978 - June 1982 M.A., Ph.D. in Economics Yale University - Sept. 1977 - June 1978 M.A. in Economics Swarthmore College - Sept. 1973 - May 1976 B.Sc. in Engineering (Civil) B.A. in Economics (with High Honors awarded by Committee of External Examiners) Selected Awards and Honours McNamara Fellowship, World Bank, to study the role of real exchange rate management in the industrialisation of East Asia, 1989-1990 Article “The Monetary Approach to Exchange Rate Determination under Rational Expectations: The Dollar- Deutschemark Case" (Journal of International Economics, February 1985) was identified by the Journal of International Economics to be one of the twenty-five most cited articles in its 30 years of history, February 2000. Distinguished Scholarly Public Service Award, University of California at Davis, 2004, in recognition of Academic and Service Contributions. Selected Public Lectures include: • Cha Chi Ming Cambridge Public Lecture on Chinese Economy, University of Cambridge, two lectures, November 1 & 3, 2004 1 • -

Ziad Joseph RAHAL Sport Mondial Et Culture Moyen-Orientale, Une

UNIVERSITÉ LILLE II U.F.R. S.T.A.P.S. 9, rue de l'Université 59790 -Ronchin THÈSE pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITE LILLE II, en Sciences et Techniques des Activités Physiques et Sportives Présentée et soutenue publiquement le 13 décembre 2017 par Ziad Joseph RAHAL Sport mondial et culture moyen-orientale, une interaction dialectique récente. Le cas du Liban. Directeur de thèse Professeur Claude SOBRY Univ. Lille, EA 7369 Membres du Jury URePSSS -Unité de Recherche Pluridiscipli- Mme Sorina CERNAIANU, Université de Craiova (Roumanie) naire Sport Santé Société, Professeur Patrick BOUCHET, Université de Dijon (rapporteur) F-59000 Professeur Michel RASPAUD, Université de Grenoble Alpes (rapporteur) M. Nadim NASSIF, Université Notre-Dame, Beyrouth (Liban) Professeur Fabien WILLE, Université Lille II (Président) Professeur Claude SOBRY, Université Lille II (Directeur de thèse) UNIVERSITÉ LILLE II U.F.R. S.T.A.P.S. 9, rue de l'Université 59790 -Ronchin THÈSE pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITE LILLE II, en Sciences et Techniques des Activités Physiques et Sportives Présentée et soutenue publiquement le 13 décembre 2017 par Ziad Joseph RAHAL Sport mondial et culture moyen-orientale, une interaction dialectique récente. Le cas du Liban. Directeur de thèse Professeur Claude SOBRY Univ. Lille, EA 7369 Membres du Jury : URePSSS -Unité de Recherche Pluridiscipli- Mme Sorina CERNAIANU, Université de Craiova (Roumanie) naire Sport Santé Société, Professeur Patrick BOUCHET, Université de Dijon (rapporteur) F-59000 Professeur Michel RASPAUD, Université de Grenoble Alpes (rapporteur) M. Nadim NASSIF, Université Notre-Dame, Beyrouth (Liban) Professeur Fabien WILLE, Université Lille 2 (Président) Professeur Claude SOBRY, Université Lille 2 (Directeur de thèse) Remerciements : Au terme de ce parcours universitaire qui aboutit aujourd’hui à la soutenance de cette thèse, il me revient d’exprimer mes plus sincères remerciements à toutes celles et ceux sans qui, ce travail n’aurait pas pu voir le jour. -

Punk Rock Workout

REPORTING FROM THE HEART OF CASCADIA cascadia 12.06.06 :: 1.39 :: FREE SLUDGE FACTORS: CLEANUP BY THE NUMBERS, P. 8 DOWNTOWN BY DESIGN: PUBLIC PARTICIPATION SETS STANDARDS, P.10 iDiOM Theater WHAT retools A Christmas THE DICKENS? Carol, p.17 SNOW REPORT: WE’RE NUMBER ONE! P.13 LOOK UP! ARTISTS PORTRAY POETRY OF THE NIGHT SKY, P. 16 PUNK ROCK WORKOUT: Pretty Girls Make Graves, P.18 31 | Food 25-29 ae Sun eds nd da | Classifi | u Build Your Own! y 22-24 S | Film Special “Sundae” Bar on 18-21 the Sunday Dinner Buffet. For a limited time only! Not Valid 12/31/06 | Music Also available for $5 as a separate purchase. 17 | Art 16 Win Gift Cards to Sears, Old Navy, Starbucks and the Nooksack Market Centre plus | On Stage hundreds in Slot Play! 13-15 13-15 Holiday | Words & Community $1,750 12 Shopping Nightly! | Get Out Drawings every Thursday Friday and Saturday 8-11 8-11 , at pm pm and pm. | News 9 , 10 11 6-7 6-7 finale on Dec. 30th! | Views $6,500 4-5 4-5 Wednesday Night Buffet | Letters 3 Buy One... Get One Do it 11.29.06 FREE! Present this coupon along with your Winner’s Club Card Just 15 min. East of Bellingham at the Buffet to receive your free meal. Both customers on the Mt. Baker Highway must be a Winner’s Club Member to redeem. One offer Cascadia Weekly | #1.38 360-592-5472 per coupon. Management reserves all rights. www.nooksackcasino.com Valid any Wednesday through 12/27/06. -

THEMA ASIA-PACIFIC Expands Its Content Portfolio with Inwild

NEWSLETTER THEMA ASIA-PACIFIC expands its content portfolio with InWild THEMA Asia-Pacific is delighted to announce its partnership with InWild TV channel. InWild is all about nature and wildlife, from all corners of the world. Nature and wildlife have always been binge-able, high- value television genres. MARCH - APRIL 2021 NEWS FRANCE French Pay-TV-Provider SFR has launched several new channels with its “Le Bouquet Africain” offer. 4 channels have been added: SunuYeuf, Novelas TV (both THEMA-edited channels) along with A+ and NCI. SFR now proposes up to 23 channels and includes the +D’AFRIQUE On Demand catalogue. EUROPE MIDDLE EAST & AFRICA Love Nature 4K is now available with Bulgarian operators Escom and New Dream TV. Museum TV HD, exclusively dedicated to art content, is now available to GO PLC subscribers in Malta. MyZen TV is henceforth available with Macedonian operator Inel Internacional. In the Middle East, subscribers to Shahid (MBC’s OTT platform) will now have access to M6 International. MBC is now available as part of Telenet’s basic package in the Netherlands. Télé Congo is now available with Telenet’s Bouquet Africain in the Netherlands. CANADA THEMA CANADA’s team is pleased to announce a new agency agreement with Horizons Sports Limited — offering the best selection of endurance sports and adventure M6 International‘s programs channel will movies, for the distribution of linear and now be available on Canadian operator nonlinear content offers with any satellite, IPTV, Vidéotron’s Helix platform. FFTx, OTT, Mobile, Cable, or any other form of network platforms in Canada. -

Le-Bouquet-Africain.Pdf

PRÉSIDENT LE MOT DU Une histoire, “Le Bouquet Africain a permis de remettre en place un lancement, des passerelles audiovisuelles entre la France et l’Afrique. une offre, C’est le fruit d’un partenariat équilibré entre entrepreneurs du Sud et du Nord, élément clef Octobre 2008, en précurseur la société THEMA annonçait le lancement du premier bouquet de chaînes télévisées africaines sur le marché français, de la formidable réussite de ce projet ” en exclusivité chez le fournisseur d’accès Internet Neuf Cegetel qui est devenu aujourd’hui SFR, puis auprès des autres FAI. Tout d’abord composé de 6 chaînes, ce bouquet offre une fenêtre d’exposition des œuvres audiovisuelles africaines sur le marché français dans un cadre technique et juridique contrôlé. Son prix, son accès simple et son contenu riche ont permis de répondre à l’attente François Thiellet, Président de Thema. légitime d’une grande partie de la population africaine vivant en France, et aux amoureux de l’Afrique. 2 3 LES CHAÎNES BASIQUE 6,90 € / mois minimum Aujourd’hui RTS - Notre mission, Informer – Eduquer – Divertir. Chaîne publique généraliste du Sénégal. ORTM - La passion du service public. Chaîne publique généraliste du Mali. LE BOUQUET AFRICAIN, C’EST : CRTV - Chaîne publique généraliste du Cameroun. RTB - Toujours au cœur des grands évènements. Chaîne publique généraliste du Burkina Faso. UNE OFFRE DE TELE CONGO - Plus jamais sans vous. Chaîne généraliste nationale publique du Congo (Brazzaville). RTI - Chaîne généraliste nationale publique de la Côte d’Ivoire. ORTB - Votre partenaire pour les grands évènements. Chaîne de télévision publique généraliste du Bénin. RTG1- Chaîne de télévision publique généraliste du Gabon. -

Board Agenda and Report Packet

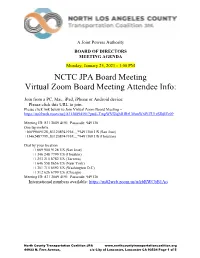

A Joint Powers Authority BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING AGENDA Monday, January 25, 2021 - 1:00 PM NCTC JPA Board Meeting Virtual Zoom Board Meeting Attendee Info: Join from a PC, Mac, iPad, iPhone or Android device: Please click this URL to join. Please click link below to Join Virtual Zoom Board Meeting – https://us02web.zoom.us/j/83120894191?pwd=TmpWVGlqMHRzU0hmWnlYZU1zSDdlZz09 Meeting ID: 831 2089 4191 Passcode: 949130 One tap mobile +16699009128,,83120894191#,,,,*949130# US (San Jose) +13462487799,,83120894191#,,,,*949130# US (Houston) Dial by your location +1 669 900 9128 US (San Jose) +1 346 248 7799 US (Houston) +1 253 215 8782 US (Tacoma) +1 646 558 8656 US (New York) +1 301 715 8592 US (Washington D.C) +1 312 626 6799 US (Chicago) Meeting ID: 831 2089 4191 Passcode: 949130 International numbers available: https://us02web.zoom.us/u/kbRWCbB1Ao North County Transportation Coalition JPA www.northcountytransportationcoalition.org 44933 N. Fern Avenue, c/o City of Lancaster, Lancaster CA 93534 Page 1 of 5 NCTC JPA BOARD OF DIRECTORS BOARD MEMBERS Chair, Supervisor Kathryn Barger, 5th Supervisorial District, County of Los Angeles Mark Pestrella, Director of Public Works, County of Los Angeles Victor Lindenheim, County of Los Angeles Austin Bishop, Council Member, City of Palmdale Laura Bettencourt, Council Member, City of Palmdale Bart Avery, City of Palmdale Marvin Crist, Vice Mayor, City of Lancaster Kenneth Mann, Council Member, City of Lancaster Jason Caudle, City Manager, City of Lancaster Marsha McLean, Council Member, City of Santa Clarita Robert Newman, Director of Public Works, City of Santa Clarita Vacant, City of Santa Clarita EX-OFFICIO BOARD MEMBERS Macy Neshati, Antelope Valley Transit Authority Adrian Aguilar, Santa Clarita Transit BOARD MEMBER ALTERNATES Dave Perry, County of Los Angeles Juan Carrillo, Council Member, City of Palmdale Mike Hennawy, City of Santa Clarita NCTC JPA STAFF Executive Director: Arthur V. -

General Conference 16Th Session 30 November – 4 December 2015, Vienna, Austria

www.unido.org General Conference 16th Session 30 November – 4 December 2015, Vienna, Austria Sustainable industrialization for shared prosperity UNIDO focusing on Sustainable Development Goals #SDG9: Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation. Contents General Conference Overview 3 Snapshot of Side Events 24 Highlights from Keynote Speeches 4 UNIDO Open Data Platform 27 The Conference in Pictures 10 Introducing UNIDO Goodwill Ambassador, Janne Vangen Solheim, Fourth UNIDO Forum on Inclusive and Norway 27 Sustainable Industrial Development 12 The Least Developed Countries Second Donor Meeting 15 Ministerial Conference 28 UNIDO’s Cooperation with the General Conference Outcomes 30 European Union and the European Investment Bank 22 Looking Forward 32 2 General Conference Overview Vienna, Austria Partnership (PCP). The PCP is being General Conference Overview piloted in Ethiopia and Senegal and has just been extended to Peru. During the Conference, participants agreed that: Sustainable • UNIDO’s thematic priorities fully reflect the economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainable development; Industrialization for • The Organization’s role will be pivotal in implementing Goal 9 and the 2030 Agenda; Shared Prosperity • UNIDO is well equipped to deliver on the SDGs to eradicate poverty, create jobs, combat environmental degradation and promote sustainable economic growth; The sixteenth session of the General “important role of UNIDO in providing • The Organization offers valuable Conference of the United Nations decent livelihoods, especially in those services which are, inter alia, helping Industrial Development Organization countries from which we are now to tackle the root causes of migration (UNIDO) took place in Vienna, Austria, receiving refugees”. by supporting job creation. -

The World Economic Forum – a Partner in Shaping History

The World Economic Forum A Partner in Shaping History The First 40 Years 1971 - 2010 The World Economic Forum A Partner in Shaping History The First 40 Years 1971 - 2010 © 2009 World Economic Forum All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system. World Economic Forum 91-93 route de la Capite CH-1223 Cologny/Geneva Switzerland Tel.: +41 (0)22 869 1212 Fax +41 (0)22 786 2744 e-mail: [email protected] www.weforum.org Photographs by swiss image.ch, Pascal Imsand and Richard Kalvar/Magnum ISBN-10: 92-95044-30-4 ISBN-13: 978-92-95044-30-2 “Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back, always ineffective, concerning all acts of initiative (and creation). There is one elementary truth the ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one’s favour all manner of unforeseen incidents and meetings and material assistance which no man could have dreamed would have come his way. Whatever you can do or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, power and magic in it. Begin it now.” Goethe CONTENTS Foreword 1 Acknowledgements 3 1971 – The First Year 5 1972 – The Triumph of an Idea 13 1973 – The Davos Manifesto 15 1974 – In the Midst of Recession 19 -

Annual Report 2004

SES GLOBAL Annual Report 2004 Yo ur Satellite Connection to the World www.ses-global.com SES C/029/04.05 E Annual Report 2004 Through our family of regional operating companies, the SES Group offers the leading portfolio of satellite-centric services around the world. 2004 2003 Financial summary EUR millions EUR millions Total revenues 1,146.6 1,207.5 EBITDA 842.1 942.8 Operating profit 307.3 371.7 Profit of the Group 229.9 205.4 Net operating cash flow 882.1 873.8 Free cash flow 222.0 940.3 Capital expenditure 531.6 317.0 Net debt 1,619.7 1,699.1 Shareholders’ equity 3,217.0 3,247.8 Earnings per A share (EUR) 0.38 0.34 Dividend per A share (EUR) 0.30* 0.22 Employees 985 789 Key performance ratios in % EBITDA margin 73.4 78.1 Net income margin 20.0 17.0 Return on average equity 7.1 6.0 Net debt / EBITDA 1.9 1.8 Net debt / shareholders’ equity 50.3 52.3 * Recommended by Directors and subject to shareholder approval. Contents SES GLOBAL S.A. consolidated accounts 4 Chairman’s statement 43 Report of the independent auditor 6 President and CEO’s statement 44 Consolidated balance sheet 46 Consolidated profit and loss account Operations review 47 Consolidated statement of cash flow 8 SES GLOBAL 48 Consolidated statement of changes in 12 SES ASTRA shareholders’ equity 18 SES AMERICOM 49 Notes to the consolidated accounts 24 Global partners SES GLOBAL S.A. annual accounts Corporate governance 71 Report of the independent auditor 29 SES GLOBAL shareholders 72 Balance sheet 30 Report of the Chairman on corporate governance 73 Profit and loss account Annual General meeting of the shareholders Statement of changes in shareholders’ equity 31 Board of Directors 74 Notes to the SES GLOBAL S.A. -

Title the TRANSFER and DIFFUSION of HUMAN RESOURCE (HR) POLICIES and PRACTICES of EUROPEAN MULTINATIONAL COMPANIES (Mncs) to THEIR NIGERIAN SUBSIDIARIES

Title THE TRANSFER AND DIFFUSION OF HUMAN RESOURCE (HR) POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF EUROPEAN MULTINATIONAL COMPANIES (MNCs) TO THEIR NIGERIAN SUBSIDIARIES Name: Dr. Janet Francis Akhile This is a digitised version of a dissertation submitted to the University of Bedfordshire. It is available to view only. This item is subject to copyright. THE TRANSFER AND DIFFUSION OF HUMAN RESOURCE (HR) POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF EUROPEAN MULTINATIONAL COMPANIES (MNCs) TO THEIR NIGERIAN SUBSIDIARIES J.F. AKHILE 2019 UNIVERSITY OF BEDFORDSHIRE i THE TRANSFER AND DIFFUSION OF HUMAN RESOURCE (HR) POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF EUROPEAN MULTINATIONAL COMPANIES (MNCs) TO THEIR NIGERIAN SUBSIDIARIES By J.F. AKHILE A thesis submitted to the University of Bedfordshire in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2019 ii THE TRANSFER AND DIFFUSION OF HUMAN RESOURCE (HR) POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF EUROPEAN MULTINATIONAL COMPANIES (MNCs) TO THEIR NIGERIAN SUBSIDIARIES J. F AKHILE ABSTRACT Human resource (HR) practices diffusion within multinational companies (MNCs) is an imperative area of research for strategic international human resource management (SIHRM). The existing literature noted that there are critical factors that affect the transfer and diffusion process of human resource practices. This research seeks to address certain shortcomings in existing SIHRM literature, in particular the lack of work on human resource policies and practices adopted by multinationals operating in developing sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries. This research extends the focus of SIHRM literature beyond MNCs parent companies into the subsidiary’s context in developing SSA country. This work builds from broader analytical frameworks to examine and interpret the dynamic underlying process of human resource practices diffused. -

Pdf, 643.50 Kb

Technological Innovation Policy in China: The Lessons, and the Necessary Changes Ahead Xiaolan Fu Technology and Management Centre for Development Department of International Development, University of Oxford [email protected] Wing Thye Woo Department of Economics, University of California, Davis Jeffrey Cheah Institute on Southeast Asia, Sunway University School of Economics, Fudan University [email protected] Jun Hou Technology and Management Centre for Development Department of International Development, University of Oxford [email protected] 29 February 2016 Abstract China has now moved considerably away from being an imitative latecomer to technology toward to being an innovation-driven economy. The key lessons from China’s experience are that (1) there is synergy between External Knowledge and Indigenous Innovation because the process of learning the tacit knowledge required in using the foreign technology fully is made easier by strong in-house R&D capability; (2) the open innovation approach is very important because it allows multiple driving forces -- the state, the private sector and MNEs – with each playing a changing role over time; and (3) the commencement of foreign technology transfer and investment in indigenous innovation should go hand in hand. Without the numerous well- funded programs to build up the innovation infrastructure to increase the absorptive capacity of Chinese firms, foreign technology would have remained static technology embedded in imported machines and would not have strengthened indigenous technological capability. However, China could still end up in the middle-income trap, unless it undertakes a series of critical reforms in its innovation regime in order to keep moving up growth trajectories that are increasingly skill-intensive and technology-intensive. -

1Dbw) =^ @Dxrz 4Gxc 5A^\ 8Ap`

M V 4G?;>A410;C8<>A4)=dlidZmeZg^ZcXZdjgcdgi]ZgccZ^\]Wdgq8]bXST Learn to Dance Classes Forming Now • Alex/Landmark • Tysons Corner • Bethesda • Gaithersburg • Silver Spring w www.arthurmurraydc.comww.arthurmurraydc.com 1 1-800-503-6769-800-503-6769 Call for free lesson © 2002 AMI, Inc. : IN;EB<:MBHG H? u PPP'P:LABG@MHGIHLM'<HF(>QIK>LL u F:K<A++%+))/u -- 5A44++ P^]g^l]Zr 1dbW)=^@dXRZ4gXc5a^\8aP` LZrl]^\blbhgmhpbma]kZp_hk\^lpbee_Zeemh_nmnk^ik^lb]^gml Ma^ik^lb]^gmlihd^_hkg^ZkerZgahnk ZmZPabm^Ahnl^g^pl\hg_^k^g\^%iZkmh_ F0B78=6C>=kIk^lb]^gm;nlalZb]Mn^l]Zr ;nlalZb]%Z\dghpe^]`bg`fblmZd^lZlma^ Zg^ph__^glbo^mh^Zl^:f^kb\ZglÍngaZi& maZm:f^kb\Zg_hk\^lpbeek^fZbgbgBkZj Ngbm^]LmZm^lpZl_hk\^]mhlpbm\amZ\mb\l ibg^llpbmama^pZkZg]_^eehpK^in[eb\ZglÍ _hkr^ZklZg]bmpbee[^nimhZ_nmnk^ik^lb& Zg]\aZg`^Zk^\hglmkn\mbhglmkZm^`rmaZm Zgqb^mrZ[hnm_Zee^e^\mbhgl'A^_Z\^]ld^imb& ]^gmmh]^\b]^pa^gmh[kbg`ma^fZeeahf^' h__^k^]mZk`^ml_hkbglnk`^gml' \Zejn^lmbhglZ[hnmBkZj]nkbg`ZgZii^Zk& ;nm]^_rbg`\kbmb\lZg]ieng`bg`iheel%a^ A^Zelhk^c^\m^]Zll^kmbhgl[rBkZjÍl_hkf^k Zg\^Fhg]Zrbg<e^o^eZg]%Zg]ieZglZghma^k ]^\eZk^]%ÊBÍfhimbfblmb\p^Íeeln\\^^]'B_ bgm^kbfikbf^fbgblm^kmaZmma^\hngmkraZ] Z]]k^lllhhghgBkZj' ghm%BÍ]ineehnkmkhhilhnm'Ë _Zee^gbgmh\bobepZkZfb]l^\mZkbZgobhe^g\^maZm In[eb\lniihkm_hkma^pZkZg]_hk;nla -ICHAEL3MITH RIGHT FACESYEARSINPRISON Ma^ik^lb]^gmk^c^\m^]\Zeel_hkma^ aZle^_mfhk^maZg*%)))BkZjbl]^Z]lbg\^ma^ abfl^e_aZl_Zee^gbgk^\^gmfhgmal%c^hi& k^lb`gZmbhgh_=^_^gl^L^\k^mZkr=hgZe] [hf[bg`eZlmfhgmah_ZLabbm^Fnlebflakbg^' Zk]bsbg`ma^ihebmb\Ze\ZibmZea^\eZbf^] 2^]eXRcTS)6Wj<]gV^WYd\ Knfl_^e]%\ab^_Zk\abm^\mh_pZklbgBkZjZg]