Nesting and Foraging by a Pair of Striped Honeyeaters at Baradine, New South Wales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birding Oxley Creek Common Brisbane, Australia

Birding Oxley Creek Common Brisbane, Australia Hugh Possingham and Mat Gilfedder – January 2011 [email protected] www.ecology.uq.edu.au 3379 9388 (h) Other photos, records and comments contributed by: Cathy Gilfedder, Mike Bennett, David Niland, Mark Roberts, Pete Kyne, Conrad Hoskin, Chris Sanderson, Angela Wardell-Johnson, Denis Mollison. This guide provides information about the birds, and how to bird on, Oxley Creek Common. This is a public park (access restricted to the yellow parts of the map, page 6). Over 185 species have been recorded on Oxley Creek Common in the last 83 years, making it one of the best birding spots in Brisbane. This guide is complimented by a full annotated list of the species seen in, or from, the Common. How to get there Oxley Creek Common is in the suburb of Rocklea and is well signposted from Sherwood Road. If approaching from the east (Ipswich Road side), pass the Rocklea Markets and turn left before the bridge crossing Oxley Creek. If approaching from the west (Sherwood side) turn right about 100 m after the bridge over Oxley Creek. The gate is always open. Amenities The main development at Oxley Creek Common is the Red Shed, which is beside the car park (plenty of space). The Red Shed has toilets (composting), water, covered seating, and BBQ facilities. The toilets close about 8pm and open very early. The paths are flat, wide and easy to walk or cycle. When to arrive The diversity of waterbirds is a feature of the Common and these can be good at any time of the day. -

Australia South Australian Outback 8Th June to 23Rd June 2021 (13 Days)

Australia South Australian Outback 8th June to 23rd June 2021 (13 days) Splendid Fairywren by Dennis Braddy RBL South Australian Outback Itinerary 2 Nowhere is Australia’s vast Outback country more varied, prolific and accessible than in the south of the country. Beginning and ending in Adelaide, we’ll traverse the region’s superb network of national parks and reserves before venturing along the remote, endemic-rich and legendary Strzelecki and Birdsville Tracks in search of a wealth of Australia’s most spectacular, specialised and enigmatic endemics such as Grey and Black Falcons, Letter-winged Kite, Black-breasted Buzzard, Chestnut- breasted and Banded Whiteface, Gibberbird, Yellow, Crimson and Orange Chats, Inland Dotterel, Flock Bronzewing, spectacular Scarlet-chested and Regent Parrots, Copperback and Cinnamon Quail- thrushes, Banded Stilt, White-browed Treecreeper, Red-lored and Gilbert’s Whistlers, an incredible array of range-restricted Grasswrens, the rare and nomadic Black and Pied Honeyeaters, Black-eared Cuckoo and the incredible Major Mitchell’s Cockatoo. THE TOUR AT A GLANCE… THE SOUTH AUTRALIAN OUTBACK ITINERARY Day 1 Arrival in Adelaide Day 2 Adelaide to Berri Days 3 & 4 Glue Pot Reserve and Calperum Station Day 5 Berri to Wilpena Pound and Flinders Ranges National Park Day 6 Wilpena Pound to Lyndhurst Day 7 Strzelecki Track Day 8 Lyndhurst to Mungerranie via Marree and Birdsville Track Day 9 Mungerranie and Birdsville Track area Day 10 Mungerranie to Port Augusta Day 11 Port Augusta area Day 12 Port Augusta to Adelaide Day 13 Adelaide and depart RBL South Australian Outback Itinerary 3 TOUR MAP… RBL South Australian Outback Itinerary 4 THE TOUR IN DETAIL… Day 1. -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania. -

Brookfield CP Bird List

Bird list for BROOKFIELD CONSERVATION PARK -34.34837 °N 139.50173 °E 34°20’54” S 139°30’06” E 54 362200 6198200 or new birdssa.asn.au ……………. …………….. …………… …………….. … …......... ……… Observers: ………………………………………………………………….. Phone: (H) ……………………………… (M) ………………………………… ..………………………………………………………………………………. Email: …………..…………………………………………………… Date: ……..…………………………. Start Time: ……………………… End Time: ……………………… Codes (leave blank for Present) D = Dead H = Heard O = Overhead B = Breeding B1 = Mating B2 = Nest Building B3 = Nest with eggs B4 = Nest with chicks B5 = Dependent fledglings B6 = Bird on nest NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. Rainbow Bee-eater Mulga Parrot Eastern Bluebonnet Red-rumped Parrot Australian Boobook *Feral Pigeon Common Bronzewing Crested Pigeon Australian Bustard Spur-winged Plover Little Buttonquail (Masked Lapwing) Painted Buttonquail Stubble Quail Cockatiel Mallee Ringneck Sulphur-crested Cockatoo (Australian Ringneck) Little Corella Yellow Rosella Black-eared Cuckoo (Crimson Rosella) Fan-tailed Cuckoo Collared Sparrowhawk Horsfield's Bronze Cuckoo Grey Teal Pallid Cuckoo Shining Bronze Cuckoo Peaceful Dove Maned Duck Pacific Black Duck Little Eagle Wedge-tailed Eagle Emu Brown Falcon Peregrine Falcon Tawny Frogmouth Galah Brown Goshawk Australasian Grebe Spotted Harrier White-faced Heron Australian Hobby Nankeen Kestrel Red-backed Kingfisher Black Kite Black-shouldered Kite Whistling Kite Laughing Kookaburra Banded Lapwing Musk Lorikeet Purple-crowned Lorikeet Malleefowl Spotted Nightjar Australian Owlet-nightjar Australian Owlet-nightjar Blue-winged Parrot Elegant Parrot If Species in BOLD are seen a “Rare Bird Record Report” should be submitted. SEASONS – Spring: September, October, November; Summer: December, January, February; Autumn: March, April May; Winter: June, July, August IT IS IMPORTANT THAT ONLY BIRDS SEEN WITHIN THE RESERVE ARE RECORDED ON THIS LIST. -

OF the TOWNSVILLE REGION LAKE ROSS the Beautiful Lake Ross Stores Over 200,000 Megalitres of Water and Supplies up to 80% of Townsville’S Drinking Water

BIRDS OF THE TOWNSVILLE REGION LAKE ROSS The beautiful Lake Ross stores over 200,000 megalitres of water and supplies up to 80% of Townsville’s drinking water. The Ross River Dam wall stretches 8.3km across the Ross River floodplain, providing additional flood mitigation benefit to downstream communities. The Dam’s extensive shallow margins and fringing woodlands provide habitat for over 200 species of birds. At times, the number of Australian Pelicans, Black Swans, Eurasian Coots and Hardhead ducks can run into the thousands – a magic sight to behold. The Dam is also the breeding area for the White-bellied Sea-Eagle and the Osprey. The park around the Dam and the base of the spillway are ideal habitat for bush birds. The borrow pits across the road from the dam also support a wide variety of water birds for some months after each wet season. Lake Ross and the borrow pits are located at the end of Riverway Drive, about 14km past Thuringowa Central. Birds likely to be seen include: Australasian Darter, Little Pied Cormorant, Australian Pelican, White-faced Heron, Little Egret, Eastern Great Egret, Intermediate Egret, Australian White Ibis, Royal Spoonbill, Black Kite, White-bellied Sea-Eagle, Australian Bustard, Rainbow Lorikeet, Pale-headed Rosella, Blue-winged Kookaburra, Rainbow Bee-eater, Helmeted Friarbird, Yellow Honeyeater, Brown Honeyeater, Spangled Drongo, White-bellied Cuckoo-shrike, Pied Butcherbird, Great Bowerbird, Nutmeg Mannikin, Olive-backed Sunbird. White-faced Heron ROSS RIVER The Ross River winds its way through Townsville from Ross Dam to the mouth of the river near the Townsville Port. -

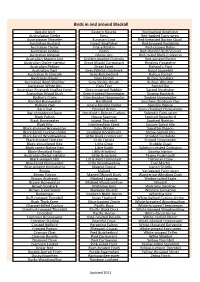

Birds in and Around Blackall

Birds in and around Blackall Apostle bird Eastern Rosella Red backed Kingfisher Australasian Grebe Emu Red-backed Fairy-wren Australasian Shoveler Eurasian Coot Red-breasted Button Quail Australian Bustard Forest Kingfisher Red-browed Pardalote Australian Darter Friary Martin Red-capped Robin Australian Hobby Galah Red-chested Buttonquail Australian Magpie Glossy Ibis Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo Australian Magpie-lark Golden-headed Cisticola Red-winged Parrot Australian Owlet-nightjar Great (Black) Cormorant Restless Flycatcher Australian Pelican Great Egret Richard’s Pipit Australian Pipit Grey (White) Goshawk Royal Spoonbill Australian Pratincole Grey Butcherbird Rufous Fantail Australian Raven Grey Fantail Rufous Songlark Australian Reed Warbler Grey Shrike-thrush Rufous Whistler Australian White Ibis Grey Teal Sacred Ibis Australian Ringneck (mallee form) Grey-crowned Babbler Sacred Kingfisher Australian Wood Duck Grey-fronted Honeyeater Singing Bushlark Baillon’s Crake Grey-headed Honeyeater Singing Honeyeater Banded Honeyeater Hardhead Southern Boobook Owl Barking Owl Hoary-headed Grebe Spinifex Pigeon Barn Owl Hooded Robin Spiny-cheeked Honeyeater Bar-shouldered Dove Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo Splendid Fairy-wren Black Falcon House Sparrow Spotted Bowerbird Black Honeyeater Inland Thornbill Spotted Nightjar Black Kite Intermediate Egret Square-tailed kite Black-chinned Honeyeater Jacky Winter Squatter Pigeon Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike Laughing Kookaburra Straw-necked Ibis Black-faced Woodswallow Little Black Cormorant Striated Pardalote -

Conserving Migratory and Nomadic Species

Conserving migratory and nomadic species Claire Alice Runge A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2015 School of Biological Sciences Abstract Migration is an incredible phenomenon. Across cultures it moves and inspires us, from the first song of a migratory bird arriving in spring, to the sight of thousands of migratory wildebeest thundering across African plains. Not only important to us as humans, migratory species play a major role in ecosystem functioning across the globe. Migratory species use multiple landscapes and can have dramatically different ecologies across their lifecycle, making huge contributions to resource fluxes and nutrient transport. However, migrants around the world are in decline. In this thesis I examine our conservation response to these declines, exploring how well current approaches account for the unique needs of migratory species, and develop ways to improve on these. The movements of migratory species across time and space make their conservation a multidimensional problem, requiring actions to mitigate threats across jurisdictions, across habitat types and across time. Incorporating such linkages can make a dramatic difference to conservation success, yet migratory species are often treated for the purposes of conservation planning as if they were stationary, ignoring the complex linkages between sites and resources. In this thesis I measure how well existing global conservation networks represent these linkages, discovering major gaps in our current protection of migratory species. I then go on to develop tools for improving conservation of migratory species across two areas: prioritizing actions across species and designing conservation networks. Protected areas are one of our most effective conservation tools, and expanding the global protected area estate remains a priority at an international level. -

A Preliminary Assessment of Faunal Values Within and Adjacent EPC 1029, Styx Basin, Central-East Queensland

A preliminary assessment of faunal values within and adjacent EPC 1029, Styx Basin, central-east Queensland ) Prepared for Yeats Consulting Engineers by Ed Meyer, Ecological Consultant,S Luscombe Street, Runcorn QLD 4113 ([email protected]) Conditions of use This report may only be used for the purposes for which it was commissioned. The use of this report, or part thereof, for any other reason or purpose is prohibited without the written consent of the author. Front cover: Fauna recorded from EPC 1029 during March 2011 surveys. Clockwise from upper left: ornamental snake (Denisonia maculata); squatter pigeon (southern race) (Geophaps scripta scripta); metallic snake-eyed skink (Cryptoblepharus metal/icus); and eastern sedgefrog (Litoria tal/ax). ©Edward Meyer 2011 5 Luscombe Street, Runcorn QLD 4113 E-mail:[email protected] Version 2 _ 3 August 2011 2 Table of contents 1. Summary 4 2. Background 6 Description of study area 6 Nomenclature 6 Abbreviations and acronyms 7 3. Methodology 9 General approach 9 ) Desktop assessment 9 Likelihood of occurrence assessments 10 Field surveys 11 Survey conditions 15 Survey limitations 15 4. Results 17 Desktop assessment findings 17 Likelihood of occurrence assessments 17 Field survey results -fauna 20 Field survey results - fauna habitat 22 Habitat for conservation significant species 28 ) 5. Summary and conclusions 37 6. References 38 Appendix A: Fauna previously recorded from Desktop Assessment Study Area 41 Appendix B: likelihood of occurrence assessments for conservation significant fauna 57 Appendix C: March 2011 survey results 73 Appendix D: Habitat photos 85 Appendix E: Habitat assessment proforma 100 3 1. Summary The faunal values of land within and adjacent Exploration Permit for Coal (EPe) 1029 were investigated by way of desktop review of existing information as well as field surveys carried out in late March 201l. -

Birds on Farms

Border Rivers Birds on Farms INTRODUCTION Grain & Graze Forty-seven mixed farms within nine regions around Australia took part in BR All collecting ecological data for the biodiversityBorder section of the nationalRivers Grain Region and Graze project. Table 1 Bird Survey Statistics Farms Farms Native bird species 105 183 This factsheet outlines the results from bird surveys, conducted in Spring 2006 and Autumn 2006-2007, on five farms within the Border Rivers Region in Introduced bird species 1 6 Queensland and New South Wales. Listed Threatened Species** 7 33 NSW Listed Species 1 11 Four paddock types were surveyed, Crop, Rotation, Pasture and Remnant (see overleaf for link to methods). Although, more bird species were recorded Priority Species 3 15 in remnant vegetation, birds were also frequently observed in other land use ** State and/or Federally types (Table 2). Table 2 List of bird species recorded in each paddock in all of the 5 Border Rivers Region farms. Food Food Common Name Preference Crop Rotation Pasture RemnantCommon Name Preference Crop Rotation Pasture Remnant Grey-crowned Babbler (N) I 1 3 1 2 3 4 Brown Goshawk IC 4 Varied Sittella I 3 White-faced Heron IC 3 White-winged Triller IGF 3 3 4 5 White-necked Heron IC 3 Striped Honeyeater IN 1 3 1 3 2 3 4 Olive-backed Oriole IF 3 Blue-faced Honeyeater IN 1 1 2 3 5 Pacific Black Duck IG 3 5 Brown Honeyeater IN 5 Little Button-quail IG 3 Red-winged Parrot G 1 1 2 5 Noisy Miner IN 4 1 2 3 4 5 3 1 2 3 4 5 Wedge-tailed Eagle C 4 2 3 5 Little Friarbird IN 1 3 Brown Thornbill I -

SBOC Full Bird List

Box 1722 Mildura Vic 3502 BirdLife Mildura - Full Bird List Please advise if you see birds not on this list Date Notes Locality March 2012 Observers # Denotes Rarer Species Emu Grey Falcon # Malleefowl Black Falcon Stubble Quail Peregrine Falcon Brown Quail Brolga Plumed Whistling-Duck Purple Swamphen Musk Duck Buff-banded Rail Freckled Duck Baillon's Crake Black Swan Australian Spotted Crake Australian Shelduck Spotless Crake Australian Wood Duck Black-tailed Native-hen Pink-eared Duck Dusky Moorhen Australasian Shoveler Eurasian Coot Grey Teal Australian Bustard # Chestnut Teal Bush Stone-curlew Pacific Black Duck Black-winged Stilt Hardhead Red-necked Avocet Blue-billed Duck Banded Stilt Australasian Grebe Red-capped Plover Hoary-headed Grebe Double-banded Plover Great Crested Grebe Inland Dotterel Rock Dove Black-fronted Dotterel Common Bronzewing Red-kneed Dotterel Crested Pigeon Banded Lapwing Diamond Dove Masked Lapwing Peaceful Dove Australian Painted Snipe # Tawny Frogmouth Latham's Snipe # Spotted Nightjar Black-tailed Godwit Australian Owlet-nightjar Bar-tailed Godwit White-throated Needletail Common Sandpiper # Fork-tailed Swift Common Greenshank Australasian Darter Marsh Sandpiper Little Pied Cormorant Wood Sandpiper # Great Cormorant Ruddy Turnstone Little Black Cormorant Red-necked Stint Pied Cormorant Sharp-tailed Sandpiper Australian Pelican Curlew Sandpiper Australasian Bittern Painted Button-quail # Australian Little Bittern Red-chested Button-quail White-necked Heron Little Button-quail Eastern Great Egret Australian -

Bird Check List

BIRD CHECK LIST Emu Cuckoos & Coucal Pelicans Fan-tailed Cuckoo(h) Australian Pelica Eagles, Hawks & Harriers Horsfield’s Bronze cuckoo Black-shouldered Kite Pheasant Coucal Stilts, Avocets & Plovers Square-tailed Kit Black-winged Stilt Black Kite Cranes Black-fronted Dotteral Whistling Kite Brolga Masked Lapwing White-bellied Sea-eagle Swamp Harrier Grebes Herons, Egrets & Bitterns Brown Goshawk Australasian Grebe(b) White-faced Heron(b) Collared Sparrowhawk Great Crested Grebe(b) White- necked Heron(b) Wedge-tailed Eagle Great Egret Little Eagle Owls & Night Birds Intermediate Egret Brown Falcon Tawny Frogmouth Nankeen Night Heron Peregrine Falcon Australian Nightjar Australian Hobby Treecreepers Nankeen Kestrel Crakes & Rails White-throated Treecreeper Purple Swamphen(b) Cockatoos & Parrots Dusky Moorhen(b) Pigeons & Doves Galah Eurasian Coot(b Emerald Dove (h) Sulphur- crested Cockatoo Darter & Cormorants Common Bronzewing (h) Rainbow Lorikeet Darter(b) Crested Pigeon Cockatiel Little Pied Cormorant(b) Squatter Pigeon Little Lorikeet Pied Cormorant Peaceful Dove Australian King Parrot Little Black Cormorant Bar-shouldered Dove Red-winged Parrot Wonga Pigeon(h) Pale-headed Rosella Swiftlets & Swifts Budgerigar White-throated Needletail Ibis, Spoonbills & Stork Fork-tailed Swift Australian White Ibis Quails Straw-necked Ibis Brown Quail Bustard Yellow-billed Spoonbill Bustard Geese, Ducks & Swan Fairy-wrens Plumed Whistling-duck(b) Kingfishers, Bee-eater & Superb Fairy-wren Wandering Whistling duck(b) Dollarbird Variegated Fairy-wren -

Assessing the Sustainability of Native Fauna in NSW State of the Catchments 2010

State of the catchments 2010 Native fauna Technical report series Monitoring, evaluation and reporting program Assessing the sustainability of native fauna in NSW State of the catchments 2010 Paul Mahon Scott King Clare O’Brien Candida Barclay Philip Gleeson Allen McIlwee Sandra Penman Martin Schulz Office of Environment and Heritage Monitoring, evaluation and reporting program Technical report series Native vegetation Native fauna Threatened species Invasive species Riverine ecosystems Groundwater Marine waters Wetlands Estuaries and coastal lakes Soil condition Land management within capability Economic sustainability and social well-being Capacity to manage natural resources © 2011 State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage The State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) has compiled this technical report in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. OEH shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to