The Rhetorics of the Past: History, Argument, and Collective Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Rhetoric?

What is Rhetoric? Rhetoric – the art of persuading someone through your speech and writing. It is a discourse (form of communication) that aims to improve the capability of writers or speakers to inform, persuade, or motivate a particular audience in certain situations. Origin – ancient Greece became the birthplace of rhetoric (effective speech/writing) in the fifth century B.C. Even Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle were arms deep in theories on the most effective means of persuasion. Examples Martin Luther King, Jr. – “I Have a Dream” Abraham Lincoln – “Gettysburg Address” There are many more famous speakers who use rhetoric. Can you think of other examples? Why is rhetoric in writing so important? Writing more effectively saves time. Things to Consider Audience – Who are you writing to? Purpose – Why are you writing this? What’s the point? Adjust your voice, tone, and persona to accommodate your communication situation. For every writing project, you can best determine what you want to say and how you want to say it by analyzing your rhetorical situation (which is sometimes called your communication situation). Learning to think rhetorically is one of the most important benefits of education! Successful leaders and decision makers are capable of making good decisions because they have learned to examine problems from a rhetorical perspective. Successful writers have learned they can write a more effective document in less time by thinking rhetorically. By simply thinking rhetorically, someone can utilize many mental activities – such as focusing on identifying the needs of a particular audience or situation. Ask yourself: Who’s going to read this? In what way can I persuade my audience? . -

Ockham's Razor and Chemistry

Ockham’s Razor and Chemistry * Roald Hoffmann, Vladimir I. Minkin, Barry K. Carpenter Abstract: We begin by presenting William of Ockham’s various formulations of his principle of parsimony, Ockham’s Razor. We then define a reaction mechanism and tell a personal story of how Ockham’s Razor entered the study of one such mechanism. A small history of methodologies related to Ock- ham’s Razor, least action and least motion, follows. This is all done in the context of the chemical (and scientific) community’s almost unthinking accep- tance of the principle as heuristically valuable. Which is not matched, to put it mildly, by current philosophical attitudes toward Ockham’s Razor. What ensues is a dialogue, pro and con. We first present a context for questioning, within chemistry, the fundamental assumption that underlies Ockham’s Ra- zor, namely that the world is simple. Then we argue that in more than one pragmatic way the Razor proves useful, without at all assuming a simple world. Ockham’s Razor is an instruction in an operating manual, not a world view. Continuing the argument, we look at the multiplicity and continuity of con- certed reaction mechanisms, and at principal component and Bayesian analysis (two ways in which Ockham’s Razor is embedded into modern statistics). The dangers to the chemical imagination from a rigid adherence to an Ockham’s Razor perspective, and the benefits of the use of this venerable and practical principle are given, we hope, their due. Keywords: Ockham’s Razor , reaction mechanism , principle of least action , prin- ciple of least motion , principal component analysis , Bayesian analysis . -

The Geologic Time Scale Is the Eon

Exploring Geologic Time Poster Illustrated Teacher's Guide #35-1145 Paper #35-1146 Laminated Background Geologic Time Scale Basics The history of the Earth covers a vast expanse of time, so scientists divide it into smaller sections that are associ- ated with particular events that have occurred in the past.The approximate time range of each time span is shown on the poster.The largest time span of the geologic time scale is the eon. It is an indefinitely long period of time that contains at least two eras. Geologic time is divided into two eons.The more ancient eon is called the Precambrian, and the more recent is the Phanerozoic. Each eon is subdivided into smaller spans called eras.The Precambrian eon is divided from most ancient into the Hadean era, Archean era, and Proterozoic era. See Figure 1. Precambrian Eon Proterozoic Era 2500 - 550 million years ago Archaean Era 3800 - 2500 million years ago Hadean Era 4600 - 3800 million years ago Figure 1. Eras of the Precambrian Eon Single-celled and simple multicelled organisms first developed during the Precambrian eon. There are many fos- sils from this time because the sea-dwelling creatures were trapped in sediments and preserved. The Phanerozoic eon is subdivided into three eras – the Paleozoic era, Mesozoic era, and Cenozoic era. An era is often divided into several smaller time spans called periods. For example, the Paleozoic era is divided into the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous,and Permian periods. Paleozoic Era Permian Period 300 - 250 million years ago Carboniferous Period 350 - 300 million years ago Devonian Period 400 - 350 million years ago Silurian Period 450 - 400 million years ago Ordovician Period 500 - 450 million years ago Cambrian Period 550 - 500 million years ago Figure 2. -

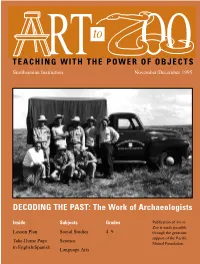

DECODING the PAST: the Work of Archaeologists

to TEACHINGRT WITH THE POWER OOOF OBJECTS Smithsonian Institution November/December 1995 DECODING THE PAST: The Work of Archaeologists Inside Subjects Grades Publication of Art to Zoo is made possible Lesson Plan Social Studies 4–9 through the generous support of the Pacific Take-Home Page Science Mutual Foundation. in English/Spanish Language Arts CONTENTS Introduction page 3 Lesson Plan Step 1 page 6 Worksheet 1 page 7 Lesson Plan Step 2 page 8 Worksheet 2 page 9 Lesson Plan Step 3 page 10 Take-Home Page page 11 Take-Home Page in Spanish page 13 Resources page 15 Art to Zoo’s purpose is to help teachers bring into their classrooms the educational power of museums and other community resources. Art to Zoo draws on the Smithsonian’s hundreds of exhibitions and programs—from art, history, and science to aviation and folklife—to create classroom- ready materials for grades four through nine. Each of the four annual issues explores a single topic through an interdisciplinary, multicultural Above photo: The layering of the soil can tell archaeologists much about the past. (Big Bend Reservoir, South Dakota) approach. The Smithsonian invites teachers to duplicate Cover photo: Smithsonian Institution archaeologists take a Art to Zoo materials for educational use. break during the River Basin Survey project, circa 1950. DECODING THE PAST: The Work of Archaeologists Whether you’re ten or one hundred years old, you have a sense of the past—the human perception of the passage of time, as recent as an hour ago or as far back as a decade ago. -

The Philosophy and Physics of Time Travel: the Possibility of Time Travel

University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well Honors Capstone Projects Student Scholarship 2017 The Philosophy and Physics of Time Travel: The Possibility of Time Travel Ramitha Rupasinghe University of Minnesota, Morris, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/honors Part of the Philosophy Commons, and the Physics Commons Recommended Citation Rupasinghe, Ramitha, "The Philosophy and Physics of Time Travel: The Possibility of Time Travel" (2017). Honors Capstone Projects. 1. https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/honors/1 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Philosophy and Physics of Time Travel: The possibility of time travel Ramitha Rupasinghe IS 4994H - Honors Capstone Project Defense Panel – Pieranna Garavaso, Michael Korth, James Togeas University of Minnesota, Morris Spring 2017 1. Introduction Time is mysterious. Philosophers and scientists have pondered the question of what time might be for centuries and yet till this day, we don’t know what it is. Everyone talks about time, in fact, it’s the most common noun per the Oxford Dictionary. It’s in everything from history to music to culture. Despite time’s mysterious nature there are a lot of things that we can discuss in a logical manner. Time travel on the other hand is even more mysterious. -

History Vs. the Past

IN JCB an occasional newsletter of the john carter brown library History vs. the Past In an incidental remark, Virginia Woolf advised a young writer: “Nothing has really he past is an “ocean of events that once happened until you have described it.” That is T happened,” explained the renowned Pol- the essential truth. ish philosopher, Leszek Kolakowski, in re- What we witness at the jcb every day are marks delivered last year after he was awarded scholars sifting through the plenitude of the the Kluge Prize ($1 million) by the Library of recorded past, both texts and images, manu- Congress. Those past events, he said, are “re- scripts and print, to construct “history”—art constructed by us on the basis of our present history, literary history, ethnohistory, and so experience—and it is only this present experi- forth. The books they are using were earlier ence, our present reconstruction of the past, efforts to articulate something about the times, that is real, not the past as such.” about past happenings. There is, then, in fact, Kolakowski spoke the obvious truth, but he should have emphasized the selectivity of that reconstruction of elements from the past, since the infinite detail and totality of the past, as of course he knows, can never be reconstructed. The writing of history is a process of highly selective reconstruction of features of the past. Confusion occurs sometimes when we use the word “history” to mean not just historical writ- ing but also as a synonym for the entirety of past happenings. “History was made today,” some reporter somewhere probably wrote when the Boston Red Sox won a world series, but the game itself did not make history; the reporter, in writing about the game, “made” history (although prob- ably not enduring history). -

Dr. Hugh Blair

; DR. HUGH BLAIR. This venerable clergyman was a lineal descendant from an antient family in the west of Scotland ; he was born on the 7th of April I71i5. The fortune of his father had been much impaired, but not so as to prevent him from giving his son a liberal education. After going through the usual course at the high school, Hugh Blair became a student at the university of Edinburgh, in October 1730. From the delicacy of his constitution he was unable to partake much in the sports of the boys, but preferred amusing himself in his solitary walks by repeating the poems of others, and sometimes attempting to make some of his own. When he became a student at the university, liis constitution grew more vigorous, and he could pursue both the amusements and the studies proper for his age. In all his classes he attracted attention, but in the logic class he was particularly distinguished and, while attending it, he composed an essay on the Beautiful, in wliich the bent of his genius first displayed itself, both to liimself and to others. In the year 1739, when the course of Mr. Blair's academical studies was nearly finished, he published a thesis, " De Fundamentis et Obligatione Legis Natures.^'' The discussion, though short, is able. After spending eleven years at the university in the study of literature, philosophy, and divinity, Mr. Blair was licensed to preach by the presbytery of Edinburgh, in 1741. In the pulpit his doctrines were sound and practical, and his language elegant : oue sermon of his in the west church was particularly noticed, it arrested the attention of a very numerous congregation. -

The End Series Topic: New Heavens & New Earth We've Been Studying “THE END” from the Book of Revelation of John. Or

The End Series Topic: New Heavens & New Earth We’ve been studying “THE END” from the Book of Revelation of John. Or in the Greek “Apokalypsis Ioannou” Apocalypse means, “uncovering” or “unveiling” REVIEW/// Whiteboard The final big picture piece we want to cover in this series. New Heaven and Earth Revelation 21 introduces the eternal future planned by God Read Revelation 21:1-7 &10-13, 16, 21, 24-26 A New Heaven and a New Earth 21 Then I saw “a new heaven and a new earth,”[a] for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and there was no longer any sea. 2 I saw the Holy City, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband. 3 And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “Look! God’s dwelling place is now among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God. 4 ‘He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death’[b] or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.” 5 He who was seated on the throne said, “I am making everything new!” Then he said, “Write this down, for these words are trustworthy and true.” 6 He said to me: “It is done. I am the Alpha and the Omega, the Beginning and the End. To the thirsty I will give water without cost from the spring of the water of life. -

Enhancing the Students' Rhetoric Attainments in Teaching of College

Sino-US English Teaching, July 2019, Vol. 16, No. 7, 300-305 doi:10.17265/1539-8072/2019.07.003 D DAVID PUBLISHING Enhancing the Students’ Rhetoric Attainments in Teaching of College English Intensive Reading ZHANG Rong-gen Shanghai Publishing and Printing College, Shanghai, China Beginning with various definitions of rhetoric, the paper gives a survey of some common English rhetoric figures found in College English intensive reading, such as metaphor, simile, transferred epithet, allusion, hyperbole, personification, metonymy, antithesis, onomatopoeia, double negative, inversion, rhetoric question, parady, transferred negation, and the like. By elaborating the functions of those rhetoric figures, the paper attempts to enhance the students’ rhetoric attainments and arouse their interest in learning English. Keywords: rhetoric attainments, rhetoric figures, College English teaching Introduction Some students often complain that the teaching of College English intensive reading course is so monotonous. It is really the case. How can a tasteless person feel his delicious food? And a certain rhetoric attainment is the prerequisite for the student to enjoy this “delicious food” of College English intensive reading course. The category of rhetoric is quite broad, one of which definitions is given by Aristotle as the art of public speaking by means of persuasion (Aristotle, 1954, pp. 2-12); and Hartwell extends the definition of rhetoric as the art of using words in speaking or writing (Hartwell & Bentley, 1982, pp. 1-15). That is to say, rhetoric contains both the art of public speaking and the method of composition. According to Chen Wangdao, a modern Chinese rhetorician, rhetoric includes both active rhetoric and passive rhetoric. -

U.S. FEI Dressage Calendar Policies and Procedures

U.S. FEI Dressage Calendar Policies and Procedures Overview The aim of these policies and procedures is to produce the most effective U.S. sporting calendar. It is important to note at the outset, that these policies and procedures do not replace the USEF Licensing and/or Mileage Rules. USEF may submit dates on the FEI calendar for events that are conditionally approved in advance of an Organizer receiving their one (1) year Federation license. However, an event/competition is not USEF approved unless and until a Federation license has been issued. Organizers must be very clear that an event appearing on the FEI Calendar does not equate to approval of the Federation license for this event. Ultimate approval lies with the USEF Board of Directors and is demonstrated by a properly executed competition licensed agreement. Applications, Review, Approval, and Fees USEF Application Deadline Applications for events wishing to be submitted to the FEI by October 1st for the following calendar year must be submitted to USEF no later than May 1. Any application after the below deadlines has NO guarantee of being submitted to the FEI for the applicable October 1st deadline. USEF Review Procedure (All dates in the following timeline are approximate) May 1 – June 15: USEF Staff and USEF Dressage Competitions Working Group will review the proposed dates and identify areas of concern and/or opportunity in the calendars. These areas of concern and/or opportunities will be communicated to the impacted OCs with the intent of working with OCs to resolve the areas of concern and/or opportunity prior to further review of the calendar. -

It's About Time: Opportunities & Challenges for U.S

I t’s About Time: Opportunities & Challenges for U.S. Geochronology About Time: Opportunities & Challenges for t’s It’s About Time: Opportunities & Challenges for U.S. Geochronology 222508_Cover_r1.indd 1 2/23/15 6:11 PM A view of the Bowen River valley, demonstrating the dramatic scenery and glacial imprint found in Fiordland National Park, New Zealand. Recent innovations in geochronology have quantified how such landscapes developed through time; Shuster et al., 2011. Photo taken Cover photo: The Grand Canyon, recording nearly two billion years of Earth history (photo courtesy of Dr. Scott Chandler) from near the summit of Sheerdown Peak (looking north); by J. Sanders. 222508_Cover.indd 2 2/21/15 8:41 AM DEEP TIME is what separates geology from all other sciences. This report presents recommendations for improving how we measure time (geochronometry) and use it to understand a broad range of Earth processes (geochronology). 222508_Text.indd 3 2/21/15 8:42 AM FRONT MATTER Written by: T. M. Harrison, S. L. Baldwin, M. Caffee, G. E. Gehrels, B. Schoene, D. L. Shuster, and B. S. Singer Reviews and other commentary provided by: S. A. Bowring, P. Copeland, R. L. Edwards, K. A. Farley, and K. V. Hodges This report is drawn from the presentations and discussions held at a workshop prior to the V.M. Goldschmidt in Sacramento, California (June 7, 2014), a discussion at the 14th International Thermochronology Conference in Chamonix, France (September 9, 2014), and a Town Hall meeting at the Geological Society of America Annual Meeting in Vancouver, Canada (October 21, 2014) This report was provided to representatives of the National Science Foundation, the U.S. -

Occam's Razor in Science: a Case Study from Biogeography

Biology and Philosophy (2007) 22:193–215 Ó Springer 2006 DOI 10.1007/s10539-006-9027-9 Occam’s Razor in science: a case study from biogeography A. BAKER Department of Philosophy, Swarthmore College, 500 College Avenue, Swarthmore, 19081, USA (e-mail: [email protected]) Received 22 June 2004; accepted 16 March 2006 Introduction There is a widespread philosophical presumption – deep-rooted and often unarticulated – that a theory whose ontology exceeds that of its competitors is at a prima facie disadvantage. This presumption that ontologically more parsi- monious theories are preferable appears in many guises. Often it remains im- plicit. Sometimes it is invoked as a primitive, self-evident proposition that cannot be further justified or elaborated upon (for example at the beginning of Good- man and Quine’s 1947 paper,1 and in Quine’s remarks about his taste for ‘‘clear skies’’ and ‘‘desert landscapes’’). Other times it is elevated to the status of a ‘‘Principle’’ and labeled as such (for example, the ‘‘Principle of Parsimony’’). However, perhaps it is best known by the name ‘‘Occam’s (or Ockham’s) Razor.’’ The question I wish to address in this paper is whether Occam’s Razor is a methodological principle of science. In addition to being a significant issue in its own right, I am also interested in potential connections between attitudes towards parsimony in science and in philosophy. Metaphysicians might once have aimed to justify the use of Occam’s Razor in science by appeal to aprioriphilosophical principles. The rise of scientific naturalism in the second half of the 20th Century has undercut this style of approach.