How Does Overeaters Anonymous Help Its Members? a Qualitative Analysis Shelly Russell-Mayhew1*,Y, Kristin M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overeaters Anonymous

WELCOME TO Overeaters Anonymous **The secretaries lines have been highlighted in blue*** Welcome to the Thursday noontime meeting of Overeaters Anonymous. My name is _____________, and I am a compulsive overeater and your leader for this meeting. Will those who wish to please join me in the Serenity Prayer: God Grant me the Serenity to accept the things I cannot change, The courage to change the things I can And the wisdom to know the difference. Are there any compulsive overeaters here beside myself? Let’s go around the room and introduce ourselves by first name only. We encourage you to: • get a sponsor to help guide your recovery • develop a plan of eating and if you wish, write it down and report daily to your sponsor • read OA-approved literature to develop a working knowledge of the Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions. The following is the OA Preamble: Overeaters Anonymous is a Fellowship of individuals who, through shared experience, strength and hope, are recovering from compulsive overeating. We welcome everyone who wants to stop eating compulsively. There are no dues or fees for members; we are self-supporting through our own contributions, neither soliciting nor accepting outside donations. OA is not affiliated with any public or private organization, political movement, ideology or religious doctrine; we take no position on outside issues. Our primary purpose is to abstain from compulsive overeating and to carry this message of recover to those who still suffer. Will _________ read “OUR INVITATION TO YOU” Our Invitation to You We of Overeaters Anonymous have made a discovery. -

Sanctuary (Spring-Summer 2016)

NEW SERIES VOLUME III, IssUE 1 Sanctuary SPRING-SUMMER 2016 A Happy Birthday in OA . CONTENTS: This is the reading from my birthday from Voices of Recovery. It reminds me of A HAPPY BIRTHDAY IN OA .... 1 my on-the-diet, off-the-diet mentality that has lost its place in my life thanks to what I’ve learned in OA. DOING WhaT WORKS .......... 1 “A poor choice or a slip used to mean, ‘I failed.’ Now I know that it’s just a FROM YOUR INTERGROUP poor choice, a slip or even the best I could do with the situation in front of me ChaIR ................................. 2 at that time on that day. It is not a door that opens to bingeing, guilt, shame COMING BacK or other self-defeating behaviors as it used to do. Grace and a healthy self-love TO STEP ONE ....................... 2 have given me this blessing through the principles of OA and the 12 steps. And awareness of all of this came from using all the tools that are always accessible OA PUZZLE 2 ..................... 3 to me no matter where I am.” GREATER DAYTON IG INTERGROUP MINUTES .......... 4 — Marilyn D. GREATER DAYTON IG Doing what works . TREASURER REPORT .............. 5 After 27 years in OA I cannot stress enough the importance for me to do what MEETING SchEDULE ......... 6–7 works. For me that means continuing to surrender what I think food is for THE OA PREAMBLE .............. 8 to my HP. It means to continue to weigh and measure my food. To be honest about why I eat what I eat. -

June 2021 OA TODAY NEWSLETTER St

June 2021 OA TODAY NEWSLETTER St. Louis Bi-State Intergroup of OA P.O. Box 28882, St. Louis, MO 63123 [email protected], www.stlouisoa.org Phone: 314-638-6070 when I can no longer tolerate the pain; pain caused by physical, emotional or spiritual distress. I became desperate again last weekend. Shame had once again imprisoned me to fear, self-pity, dramatization, and guilt. I prayed for relief. The more I prayed, the more shame exerted its power to alienate me from HP and OA. I was desperate to be nearer to God. Shame kept pushing me further away. Desperate words finally cried out from my heart. I admitted falling prey to shame again STEP SIX and again. I apologized for believing the lies of my disease, saying, “I’ll never be good Were entirely ready to have God remove enough, I can’t be healed.” I asked to be all these defects of character. given strength and courage to open my heart to The Truth when shame crept into the cracks of my sacred wounds. I asked for wisdom to know the difference Desperation Can Help Us between my work and God’s work. I admitted Prepare Our Hearts for Change my belief God is responsible for the miraculous changes I’ve experienced in Step 6 is preparing (willingness) for the action Program. of asking required in Step 7. Defects are brought to light in Steps 4 and 5. My defects Surrender. Surrender helped me to let go and are behaviors, beliefs, and actions that cause be assured God will indeed sustain me. -

February 2014

Together We Can A Publication of the Overeaters Anonymous Metro DC Intergroup February 2014 SEXUALITY AND THE OA PROGRAM STUCK Roughly aIntergroup year and a half ago, I heard Some animal is stuck in my kitchen fan! someone “qualify” for her very first time. Making ongoing scratching noises She started with the phrase: “I can’t What the heck is that? talk about my compulsive eating history without talking about my sexuality too.” Sounds like he or she is desperately For the speaker, and the other members trying to get out gathered around the table of this Overeaters Anonymous meeting, both the How long will it be immediate and the after-effects have Assuming it is stuck been profound. Occasionally, some of us Assuming it wants out in the room that night had heard qualifications in which people spoke It may go until it is too tired about their personal history of sexual Or dead abuse; but on this night, 4 out of the 6 Not before attendees shared pieces of their own sexual abuse histories. Out of desperation Unfortunately, sexual abuse is all too Because that is the only thing it knows common for many of us in the program. to do It is often at the crux of continued Sort of like a compulsion overeating. We pack on the weight and It HAS to do it keep others physically away from us. It HAS to do it Others, like me, have shielded ourselves It HAS to do it from intimacy through our verbal and non-verbal behavior. And the notion of No brain involved trusting anybody and anything, much But a desperate attempt less ourselves, can make having a To relieve the pain spiritual connection nearly impossible. -

HOW to FIND a RECOVERY GROUP: MUTUAL HELP IS MORE THAN SELF-HELP William Doverspike, Ph.D

HOW TO FIND A RECOVERY GROUP: MUTUAL HELP IS MORE THAN SELF-HELP William Doverspike, Ph.D. Drdoverspike.com 770-913-0506 One of the most common statements heard in alcohol problems. A promising strategy mutual-support recovery groups is the involves assigning a person to alternative following: “I don’t need a self-help group. If I treatments based on specific needs and could have done it alone, I wouldn’t have characteristics of the individual. needed you.” Traditional Recovery Groups Beginning with Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), In addition to AA, there are also recovery which celebrated its 80th International groups for families and friends of alcoholics Convention of 70,000 sober alcoholics who met (Al-Anon) as well as children of alcoholics at the World Congress Center in Atlanta in July (Alateen). Mutual help recovery groups are also 2015, there are approximately 400 variations of available for those who suffer from narcotics 12 Step programs that have emerged. Two addiction to (Narcotics Anonymous), as well as decades ago, a monumental survey published in families and friends those affected by such Consumer Reports (1995) revealed that AA addiction (Nar-Anon). scored significantly better (251) than mental health professionals such as psychiatrists (226), In the metro Atlanta area, there are hundreds of social workers (225), psychologists (220), weekly AA and Al-Anon meetings. Many of family physicians (213) and marriage these meetings are held in churches and counselors (208). Although this survey was not synagogues, although AA and Al-Anon is not a scientific study, the readers of Consumer affiliated with any sect, religion, sect, Reports highlighted the popularity of mutual denomination, political entity, organization, or help recovery groups. -

Welcome, Newcomers, to OA

Welcome, Newcomers, to OA This document is intended to provide you with some helpful materials to supplement those provided by the World Service Organization (WSO) of OA. Some prayers are included here because OA emphasizes a spiritual (not religious) approach for overcoming all types of eating problems. This is an important way in which OA differs from other weight-control solutions you may have tried or read about. OA proposes a 3-pronged approach – physical, emotional and spiritual. We share our knowledge and experience with each other unselfishly. Regarding the concept of “spiritual” vs. “religious,” OA basic tenets and literature use the terms “God” and “Higher Power” interchangeably and they are usually capitalized, even though they do not refer to any specific religious deity. When “God” is used, it is always understood as “God as we (you) understand God,” and every member is invited to define a higher power in whatever way they choose - religious, agnostic, atheistic or something entirely personal. If you do hear religious references at any OA meeting, please know that this is not in keeping with OA policy as a whole. We hope you will find these materials helpful in your own journey in OA. Sincerely, The Trusted Servants of OA Foot Steps VIG #09670 1 | Page Overeaters Anonymous Preamble Overeaters Anonymous is a Fellowship of individuals who, through shared experience, strength and hope, are recovering from compulsive overeating. We welcome everyone who wants to stop eating compulsively. There are no dues or fees for members; we are self-supporting through our own contributions, neither soliciting nor accepting outside donations. -

The Twelve Traditions of OA

SUPPORTING GROUPS AND SERVICE BODIES The Twelve Traditions of Overeaters Anonymous Our common welfare should come first; personal recovery depends upon OA unity The Twelve Traditions 1. Our common welfare should come first; personal recovery depends upon OA unity. 2. For our group purpose there is but one ul- timate authority—a loving God as He may express Himself in our group conscience. Our leaders are but trusted servants; they do not govern. 3. The only requirement for OA membership is a desire to stop eating compulsively. 4. Each group should be autonomous except in matters affecting other groups or OA as a whole. 5. Each group has but one primary purpose— to carry its message to the compulsive over- eater who still suffers. 6. An OA group ought never endorse, finance or lend the OA name to any related facility or outside enterprise, lest problems of mon- ey, property and prestige divert us from our primary purpose. 7. Every OA group ought to be fully self- supporting, declining outside contributions. 8. Overeaters Anonymous should remain forever nonprofessional, but our service centers may employ special workers. 9. OA, as such, ought never be organized; but we may create service boards or commit- tees directly responsible to those they serve. 10. Overeaters Anonymous has no opinion on outside issues; hence the OA name ought never be drawn into public controversy. 11. Our public relations policy is based on at- traction rather than promotion; we need always maintain personal anonymity at the level of press, radio, films, television and other public media of communication. -

Newcomers Meetings: a Leader's

NEWCOMERS MEETINGS: A LEADER’S KIT A guide for leaders and other OA members interested in meetings for beginning members CONTENTS Types of Meetings ................................................1 Meeting Arrangements........................................1 Suggestions for Leaders and Speakers ..............2 Meeting Topics .....................................................2 Overeaters Anonymous, Inc. World Service Office 6075 Zenith Court NE Rio Rancho, NM 87144-6424 USA Mail address: P.O. Box 44727 Rio Rancho, NM 87174-4727 USA Tel: 1-505-891-2664 • Fax: 1-505-891-4320 [email protected] • www.oa.org OA Board-Approved Literature © 2003 Overeaters Anonymous, Inc. All rights reserved. Rev. August 2021. 740 The kit includes the following items: A Guide for Sponsors (#200) A Lifetime of Abstinence (#155) In OA, Recovery is Possible (#135) A New Plan of Eating (#144) Fifteen Questions (#755) Many Symptoms, One Solution (#106) OA Handbook for Members, Groups, and Service Bodies (#120) OA Literature Order Form Pocket Reference for OA Members (#435) Strong Abstinence Checklist and Writing Exercise (#415) Think First (#109) To the Family of the Compulsive Eater (#240) To the Man (#290) To the Young Person (#280) Tools of Recovery (#160) Newcomers meetings introduce newcomers to the basics of our program. Topics include the three-fold nature of the disease of compulsive eating (physical, emotional, and spiritual); abstaining from compulsive eating; the Twelve Steps; the Twelve Traditions; and the Tools of Recovery. TYPES OF NEWCOMERS MEETINGS 1. Public information. These meetings are usually open to professionals, family, and friends as well as newcomers. The topics are usually covered in one or two specially scheduled two- to three-hour meetings. -

A Sponsor's Toolbox (For the Sponsorship Day Workshop)

A SPONSOR’S TOOLBOX OA HOLIDAY WORKSHOP: SPONSORSHIP DAY Getting a Newcomer Started and Other General Information for Sponsors PREPARATION It may be helpful for a new sponsor to study the OA pamphlets A Guide for Sponsors, Sponsoring Through the Twelve Steps, and Where Do I Start?, plus the oa.org download Temporary Sponsors: Newcomers’ First Twelve Days. MATERIALS • A Guide for Sponsors • Sponsoring Through the Twelve Steps • Where Do I Start? Everything a Newcomer Needs to Know • Temporary Sponsors: Newcomers’ First Twelve Days • Alcoholics Anonymous, Fourth Edition • OA and AA Twelve and Twelve • The Twelve Step Workbook of Overeaters Anonymous, Second Edition • Twelve Step Workshop and Study Guide, Second Edition • Getting Honest About Your Food and Weight – 3 column exercise (attached) • Food Slip Inventory – Slips are learning experiences. What did you learn? (attached) • Sponsorship Success podcasts at oa.org/sponsorship-success: o What is a sponsor? o Why should you get a sponsor and how can you get a sponsor? o Why be a sponsor? Why be a sponsee? o When can you start sponsoring? When can you start being sponsored? o What are the sponsorship job descriptions – from sponsor to sponsee and back? o How can you break down the barriers for both parties? o What are some different sponsoring styles? o How do you work the Twelve Steps with a sponsee? o How do you work the Twelve Traditions with a sponsee? GENERAL THOUGHTS ON GETTING NEWCOMERS STARTED • Set a time to talk or meet. Both the sponsor and sponsee should have a copy of Where Do I Start? for use at the meeting. -

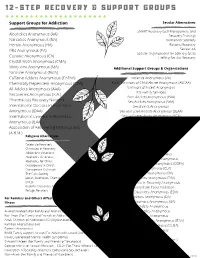

12-Step Recovery Groups

1 2 - S T E P R E C O V E R Y & S U P P O R T G R O U P S Support Groups for Addiction Secular Alternatives SMART Recovery (Self-Management and Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) Recovery Training) Narcotics Anonymous (NA) Women for Sobriety Heroin Anonymous (HA) Rational Recovery Pills Anonymous (PA) Secular AA Secular Organizations for Sobriety (SOS) Cocaine Anonymous (CA) LifeRing Secular Recovery Crystal Meth Anonymous (CMA) Marijuana Anonymous (MA) Additional Support Groups & Organizations Nicotine Anonymous (NicA) Caffeine Addicts Anonymous (CAFAA) Violence Anonymous (VA) Chemically Dependent Anonymous (CDA) Adult Survivors of Child Abuse Anonymous (ASCAA) All Addicts Anonymous (AAA) Survivors of Incest Anonymous lDS Family Services Recoveries Anonymous (R.A.) Porn Addicts Anonymous (PAA) Pharmacists Recovery Network Sex Addicts Anonymous (SAA) International Doctors in Alcoholics Sexaholics Anonymous Anonymous (IDAA) Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous (SLAA) International Lawyers in Alcoholics Sexual Compulsives Anonymous (SCA) Anonymous (ILAA) Sexual Recovery ANonymous (SRA) Association of Recovering Motorcyclists Co-dependents Anonymous (CoDa) Emotions Anonymous (A.R.M.) Religious Alternatives Dual Recovery Anonymous Depressed Anonymous Celebrate Recovery Social Anxiety Anonymous Christians in Recovery PTSD Anonymous Addictions Victorious Self Mutilators Anonymous Alcoholics Victorious Obsessive Compulsive Anonymous Alcoholics for Christ Obsessive Skin Pickers Anonymous (OSPA) Overcomers in Christ Overcomers Outreach Clutters Anonymous (CLA) -

The Compulsive Overeater in the Military

THE COMPULSIVE OVEREATER IN TO THE MILITARY The only thing that is required is that you have a desire to stop eating compulsively The Twelve Steps 1. We admitted we were powerless over food—that our lives had become unman- ageable. 2. Came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity. 3. Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him. 4. Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves. 5. Admitted to God, to ourselves and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs. 6. Were entirely ready to have God remove all these defects of character. 7. Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings. 8. Made a list of all persons we had harmed, and became willing to make amends to them all. 9. Made direct amends to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others. 10. Continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong, promptly admitted it. 11. Sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God as we understood Him, praying only for knowledge of His will for us and the power to carry that out. 12. Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these Steps, we tried to carry this message to compulsive overeaters and to practice these principles in all our affairs. Permission to use the Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous for adaptation granted by AA World Services, Inc. TO THE COMPULSIVE OVEREATER IN THE MILITARY A major aspect of military life is discipline: the greater the discipline, the more pro- fessional the military member. -

Table of Contents

Overeaters Anonymous Unity Intergroup New Representative Orientation Manual Table of Contents Welcome to Unity Intergroup .............................................................................. 1 Business Assembly 101......................................................................................... 2 Things To Know ........................................................................................................... 3 UIG Standing Committees .................................................................................... 5 OA-Approved Literature List ................................................................................ 6 Books ........................................................................................................................... 6 Pamphlets And Other Materials ................................................................................. 6 OA Board-Approved Literature And Material ............................................................. 7 Books ........................................................................................................................... 7 Pamphlets And Other Materials ................................................................................. 7 Meeting Formats ......................................................................................................... 8 Public Information Materials ...................................................................................... 8 Periodicals ..................................................................................................................