Fair Trial Concerns in Casement Park Trials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990

From ‘as British as Finchley’ to ‘no selfish strategic interest’: Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990 Fiona Diane McKelvey, BA (Hons), MRes Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences of Ulster University A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Ulster University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 I confirm that the word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words excluding the title page, contents, acknowledgements, summary or abstract, abbreviations, footnotes, diagrams, maps, illustrations, tables, appendices, and references or bibliography Contents Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Abbreviations iii List of Tables v Introduction An Unrequited Love Affair? Unionism and Conservatism, 1885-1979 1 Research Questions, Contribution to Knowledge, Research Methods, Methodology and Structure of Thesis 1 Playing the Orange Card: Westminster and the Home Rule Crises, 1885-1921 10 The Realm of ‘old unhappy far-off things and battles long ago’: Ulster Unionists at Westminster after 1921 18 ‘For God's sake bring me a large Scotch. What a bloody awful country’: 1950-1974 22 Thatcher on the Road to Number Ten, 1975-1979 26 Conclusion 28 Chapter 1 Jack Lynch, Charles J. Haughey and Margaret Thatcher, 1979-1981 31 'Rise and Follow Charlie': Haughey's Journey from the Backbenches to the Taoiseach's Office 34 The Atkins Talks 40 Haughey’s Search for the ‘glittering prize’ 45 The Haughey-Thatcher Meetings 49 Conclusion 65 Chapter 2 Crisis in Ireland: The Hunger Strikes, 1980-1981 -

Reflections on Masculinity Within Northern Ireland's Protestant

The Ulster Boys: reflections on masculinity within Northern Ireland’s Protestant community Alan Bairner (Loughborough University, UK) Introduction According to MacInnes (1998: 2), ‘masculinity does not exist as the property, character trait or aspect of identity of individuals’. Rather, ‘it is an ideology produced by men as a result of the threat posed to the survival of the patriarchal sexual division of labour by the rise of modernity’ (p. 45). Whilst the influence of a perceived ‘crisis of masculinity’ can be overstated, it is irrefutable that many of the traditional sources of male (or, to be more precise, masculine) identity have been eroded throughout the western world (Seidler, 1997).That is not to say that new sources for the construction of masculinity cannot be found. Nor is it intended to imply that men have never previously experienced conflicts of identity. This lecture discusses the construction of masculinity and the related issue of conflicted identity within the context of Northern Ireland’s Protestant community. It begins with some general observations and proceeds to discuss the trajectory of three celebrity Ulster Protestants, two of them sportsmen, and their respective engagement with conflicted identity. As Sugden (1996: 129) notes in his sociological study of boxing, Northern Ireland, and, most significantly, its major city, Belfast, has always been regarded as a home to ‘hard men’. According to Sugden, ‘the “hard men” of the pre-1950s were those who worked in 1 the shipyards, mills and factories, inhabiting a proud, physically tough and exclusively male occupational culture which cast a long shadow over popular recreation outside the workplace’. -

In Defense of Propaganda: the Republican Response to State

IN DEFENSE OF PROPAGANDA: THE REPUBLICAN RESPONSE TO STATE CREATED NARRATIVES WHICH SILENCED POLITICAL SPEECH DURING THE NORTHERN IRISH CONFLICT, 1968-1998 A thesis presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with a Degree of Bachelor of Science in Journalism By Selina Nadeau April 2017 1 This thesis is approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the Department of Journalism Dr. Aimee Edmondson Professor, Journalism Thesis Adviser Dr. Bernhard Debatin Director of Studies, Journalism Dr. Jeremy Webster Dean, Honors Tutorial College 2 Table of Contents 1. History 2. Literature Review 2.1. Reframing the Conflict 2.2.Scholarship about Terrorism in Northern Ireland 2.3.Media Coverage of the Conflict 3. Theoretical Frameworks 3.1.Media Theory 3.2.Theories of Ethnic Identity and Conflict 3.3.Colonialism 3.4.Direct rule 3.5.British Counterterrorism 4. Research Methods 5. Researching the Troubles 5.1.A student walks down the Falls Road 6. Media Censorship during the Troubles 7. Finding Meaning in the Posters from the Troubles 7.1.Claims of Abuse of State Power 7.1.1. Social, political or economic grievances 7.1.2. Criticism of Government Officials 7.1.3. Criticism of the police, army or security forces 7.1.4. Criticism of media or censorship of media 7.2.Calls for Peace 7.2.1. Calls for inclusive all-party peace talks 7.2.2. British withdrawal as the solution 7.3.Appeals to Rights, Freedom, or Liberty 7.3.1. Demands of the Civil Rights Movement 7.3.2. -

When Art Becomes Political: an Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence History & Classics Undergraduate Theses History & Classics 12-15-2018 When Art Becomes Political: An Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011 Maura Wester Providence College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/history_undergrad_theses Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the European History Commons Wester, Maura, "When Art Becomes Political: An Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011" (2018). History & Classics Undergraduate Theses. 6. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/history_undergrad_theses/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History & Classics at DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in History & Classics Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. When Art Becomes Political: An Analysis of Irish Republican Murals 1981 to 2011 by Maura Wester HIS 490 History Honors Thesis Department of History and Classics Providence College Fall 2018 For my Mom and Dad, who encouraged a love of history and showed me what it means to be Irish-American. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………… 1 Outbreak of The Troubles, First Murals CHAPTER ONE …………………………………………………………………….. 11 1981-1989: The Hunger Strike, Republican Growth and Resilience CHAPTER TWO ……………………………………………………………………. 24 1990-1998: Peace Process and Good Friday Agreement CHAPTER THREE ………………………………………………………………… 38 The 2000s/2010s: Murals Post-Peace Agreement CONCLUSION……………………………………………………………………… 59 BIBLIOGRAPHY …………………………………………………………………… 63 iv 1 INTRODUCTION For nearly thirty years in the late twentieth century, sectarian violence between Irish Catholics and Ulster Protestants plagued Northern Ireland. Referred to as “the Troubles,” the violence officially lasted from 1969, when British troops were deployed to the region, until 1998, when the peace agreement, the Good Friday Agreement, was signed. -

Conflict, the Rise of Nations, and the Decay of States: The

Taylor, Peter.Loyalists: War and Peace in Northern Ireland.New York: TV Books, 1999. The Northern Irish terrorist war has by far the greatest ratio of books to casualties: there may be more books than dead. Up until the last decade there was a major gap in the coverage of the three-sided war, namely the loyalist terrorists - or paramilitaries, as they are euphemistically called in Northern Ireland along with the Republicans. Most authors concentrated on the history of "the Troubles" from other perspectives, especially accounts of the British counterinsurgency effort or histories of the Provisional IRA. The only loyalist accounts were a history of the Ulster Volunteer Force by journalist David Boulton in 1973, and an examination of political murder co-authored by two Belfast journalists. This began to change with the publication of Belfast journalist Martin Dillon's The Shankill Butchers in 1989. But this account was almost more in the true crime genre than a military study of the paramilitaries. This was followed by Dillon's Stone Cold, the biography of Ulster Freedom Fighter (UFF - the military wing of the Ulster Defense Association) Michael Stone in 1992. That same year Scottish academic Steve Bruce published an academic analysis of the loyalist terrorists, Red Hand: The Protestant Paramilitaries in Northern Ireland. Bruce wrote a second, shorter work two years later which brought his account up to the loyalist ceasefire of 1994. Unfortunately for outsiders, Bruce and Dillon differed on several points and had little mutual respect. Dillon also wrote about UVF rebel Billy "King Rat" Wright in his 1997 God and the Gun. -

Craobh Peile Uladh2o2o Muineachán an Cabhánversus First Round Saturday 31St October St Tiernach’S Park

CRAOBH PEILE ULADH2O2O MUINEACHÁN AN CABHÁNVERSUS FIRST ROUND SATURDAY 31ST OCTOBER ST TIERNACH’S PARK. 1.15 PM DÚN NA NGALL TÍR VERSUSEOGHAIN QUARTER FINAL SUNDAY 1ST NOVEMBER PÁIRC MACCUMHAILL - 1.30PM DOIRE ARD VERSUSMHACHA QUARTER FINAL SUNDAY 1ST NOVEMBER CELTIC PARK - 4.00 PM RÚNAI: ULSTER.GAA.IE 8 The stands may be silent but we know our communities are standing tall behind us. Help us make your SuperFan voice heard by sharing a video of how you Support Where You’re From on: @supervalu_irl @SuperValuIreland using the #SuperValuSuperFans SUPPORT 371 CRAOBH PEILE ULADH2O2O Where You’re From THIS WEEKEND’S (ALL GAMESGA ARE SUBJECTMES TO WINNER ON THE DAY) @ STVERSUS TIERNACH’S PARK, CLONES SATURDAY 31ST OCTOBER WATCH LIVE ON Ulster GAA Football Senior Championship Round 1 (1:15pm) Réiteoir: Ciaran Branagan (An Dún) Réiteoir ar fuaireachas: Barry Cassidy (Doire) Maor Líne: Cormac Reilly (An Mhí) Oifigeach Taobhlíne: Padraig Hughes (Ard Mhacha) Maoir: Mickey Curran, Conor Curran, Marty Brady & Gavin Corrigan @ PÁIRCVERSUS MAC CUMHAILL, BALLYBOFEY SUNDAY 1ST NOVEMBER WATCH LIVE ON Ulster GAA Football Senior Championship Q Final (1:30pm) Réiteoir: Joe McQuillan (An Cabhán) Réiteoir ar fuaireachas: David Gough (An Mhí) Maor Líne: Barry Judge (Sligeach) Oifigeach Taobhlíne: John Gilmartin (Sligeach) Maoir: Ciaran Brady, Mickey Lee, Jimmy Galligan & TP Gray VERSUS@ CELTIC PARK, DERRY SUNDAY 1ST NOVEMBER WATCH LIVE ON Ulster GAA Football Senior Championship Q Final (4:00pm) Réiteoir: Sean Hurson (Tír Eoghain) Réiteoir ar fuaireachas: Martin McNally (Muineachán) Maor Líne: Sean Laverty (Aontroim) Oifigeach Taobhlíne: Niall McKenna (Muineachán) Maoir: Cathal Forbes, Martin Coney, Mel Taggart & Martin Conway 832 CRAOBH PEILE ULADH2O2O 57 CRAOBH PEILE ULADH2O2O 11422 - UIC Ulster GAA ad.indd 1 10/01/2020 13:53 PRESIDENT’S FOREWORD Fearadh na fáilte romhaibh chuig Craobhchomórtas games. -

“A Peace of Sorts”: a Cultural History of the Belfast Agreement, 1998 to 2007 Eamonn Mcnamara

“A Peace of Sorts”: A Cultural History of the Belfast Agreement, 1998 to 2007 Eamonn McNamara A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy, Australian National University, March 2017 Declaration ii Acknowledgements I would first like to thank Professor Nicholas Brown who agreed to supervise me back in October 2014. Your generosity, insight, patience and hard work have made this thesis what it is. I would also like to thank Dr Ben Mercer, your helpful and perceptive insights not only contributed enormously to my thesis, but helped fund my research by hiring and mentoring me as a tutor. Thank you to Emeritus Professor Elizabeth Malcolm whose knowledge and experience thoroughly enhanced this thesis. I could not have asked for a better panel. I would also like to thank the academic and administrative staff of the ANU’s School of History for their encouragement and support, in Monday afternoon tea, seminars throughout my candidature and especially useful feedback during my Thesis Proposal and Pre-Submission Presentations. I would like to thank the McClay Library at Queen’s University Belfast for allowing me access to their collections and the generous staff of the Linen Hall Library, Belfast City Library and Belfast’s Newspaper Library for all their help. Also thanks to my local libraries, the NLA and the ANU’s Chifley and Menzies libraries. A big thank you to Niamh Baker of the BBC Archives in Belfast for allowing me access to the collection. I would also like to acknowledge Bertie Ahern, Seán Neeson and John Lindsay for their insightful interviews and conversations that added a personal dimension to this thesis. -

Examining the Psychology of Women Participating in Non-State Armed Groups

Gender and Violent Extremism: Examining the Psychology of Women Participating in Non-State Armed Groups by Rebecca Dougherty and P. Kathleen Frier Master of Arts, May 2016 The George Washington University Submitted to The Faculty of The Elliott School of International Affairs of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 13, 2016 Directed by Rebecca Patterson PhD, National Security Policy © Copyright 2016 by Dougherty and Frier All rights reserved ii Dedication The authors wish to dedicate this publication to the family and friends whose support made this project possible. With special thanks to our advisor Dr. Rebecca Patterson, whose guidance and patience have made this a far better report than we could have imagined. We would also like to specially thank Drs. Aisling Swaine and Bill Rolston, whose invaluable advice made our field research possible. iii Acknowledgments The authors wish to acknowledge their fellow graduate students whose peer review during the last year was critical in improving the quality of this report: Jelle Barkema, James Bieszka, Samuel Baynes, Ivana Djukic, Steven Inglis, Katherine Kaneshiro, Diana Montealegre, and Adam Yefet. iv Abstract Gender and Violent Extremism: Examining the Psychology of Women Participating in Non-State Armed Groups There is a presumption that women do not use violence as a means of exercising their political will, because most traditional notions of femininity emphasize motherhood, peacefulness, and stability. Like the repressive power relations between men and women in Islamic State society, the norms that dominated Western culture throughout the early 20th century mirror those affecting women under the IS regime in many ways. -

Age-Friendly Belfast Baseline Report May 14

Baseline Report 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 Age-friendly Belfast Baseline Report CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................ 1 1. INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXT ....................................................................... 7 2. DEMOGRAPHY ............................................................................................... 166 3. DEPRIVATION AND POVERTY ...................................................................... 222 4. OUTDOOR SPACES & BUILDINGS ................................................................. 29 5. TRANSPORTATION .......................................................................................... 34 6. HOUSING .......................................................................................................... 43 7. SOCIAL PARTICIPATION ................................................................................. 56 8. RESPECT & SOCIAL INCLUSION .................................................................... 61 9. CIVIC PARTICIPATION & EMPLOYMENT ....................................................... 66 10. COMMUNICATION & INFORMATION ........................................................... 74 11. COMMUNITY SUPPORT & HEALTH SERVICES ......................................... 78 12. STRATEGIC CONTEXT ................................................................................. 90 13. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS .............................................. 95 APPENDICES APPENDIX 1 SOAs with -

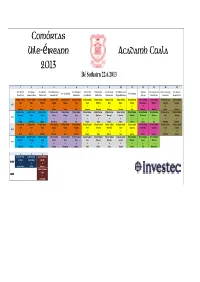

Comórtas Uile-Éireann 2013 Acadamh Cuala

Comórtas Uile-Éireann Acadamh Cuala 2013 Dé Sathairn 22.6.2013 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Páirc Parnell Staid Semple Páirc Mhic Éil Páirc Mhic Easmainn Páirc Uí Nualláin Páirc de hÍde Páirc Bhreifne Páirc Ó Conaire Páirc Mhic Gearailt Eachroim Páirc Loch Garman Páirc an Phiarsaigh Páirc Brewster Páirc Ui Chaoimh Páirc Tailteann Parnell Park Semple stadium McHale Park Casement Park Nowlan Park Dr. Hyde Park Breffni Park O'Connor Park Fitzgerald Stadium Aughrim Wexford Park Pearse Park Brewster Park 07 Boys Football 07 Boys Football 07 Boys Football 07 Boys Football 07 Boys Football 07 Boys Football 05 Boys Hurling 05 Boys Hurling 05 Boys Hurling 05 Boys Hurling 05 Boys Hurling 04 Girls Camogie 04 Girls Camogie 04 Boys Hurling 04 Boys Hurling Cork Mayo Wexford Armagh Galway Clare Cavan Wexford Kerry Mayo Galway Roscommon Kilkenny Limerick Donegal 10:15 v v v v v v v v v v v v v vs v Tipperary Meath Donegal Kilkenny Tyrone Kerry Tipperary Waterford Kilkenny Donegal Cork Tipperary Wexford Galway Tipperary 06 Girls Hurling 06 Girls Hurling 06 Girls Hurling 07 Girls Hurling 07 Girls Hurling 07 Girls Hurling 06 Boys Hurling 06 Boys Hurling 06 Boys Hurling 06 Boys Hurling 05 Girls Hurling 05 Girls Hurling 05 Girls Hurling 04 Boys Hurling 04 Boys Football Tipperary Mayo Carlow Kildare Galway Kerry Cork Tipperary Donegal Limerick Wicklow Westmeath Kilkenny Cork Donegal 10:45 v v v v v v v v v v v v v v v Armagh Waterford Galway Monaghan Limerick Cork Kildare Down Galway Kerry Antrim Galway Clare Waterford Tipperary 07 Boys Hurling 07 Boys -

![Spring Festival Fane 19 [V4]CH (S)P [ONLINE].Qxp Layout 1 14/02/2019 09:09 Page 3](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7952/spring-festival-fane-19-v4-ch-s-p-online-qxp-layout-1-14-02-2019-09-09-page-3-2597952.webp)

Spring Festival Fane 19 [V4]CH (S)P [ONLINE].Qxp Layout 1 14/02/2019 09:09 Page 3

FanE 19 [v4]CH (s)p [ONLINE].qxp_Layout 1 14/02/2019 09:09 Page 1 1-18 March 2019 FÉILE AN SPRING EARRAIGH FESTIVAL LIVE MUSIC|TALKS THEATRE |FAMILY & ST PATRICK’S DAY 1 FUN + MORE! FanE 19 [v4]CH (s)p [ONLINE].qxp_Layout 1 14/02/2019 09:09 Page 2 FÁILTE AGUS SLÁN ABHAILE Féile wishes everyone a great time at this year’s events. Get home safe with our festival transport partners Belfast Taxis CIC, Value Cabs, Translink Metro and Glider. Travel with Translink Make Smart Moves with a DayLink TACSAITHE BHÉAL FEIRSTE smartcard: £3.50 all day travel or Cuideachta Leas an Phobail £3.00 after 9.30am. BELFAST TAXIS C.I.C Click www.translink.co.uk Call 028 90 66 66 30 Tweet @Translink_NI #smartmovers (028) 90 80 90 80 Music on Metro / Gigs on Glider Ceol ar an Metro! / Gigeanna ar an Féile an Phobail Glider www.feilebelfast.com Traditional musicians from Andersonstown Contemporary and Traditional School of Music will board buses to entertain Féile an Phobail passengers. Various Metro routes to and from West Belfast on 141 – 143 Falls Road Wednesday to Friday and Glider on Saturday. Sponsored by Gaeltacht Quarter Translink Metro and Glider. Belfast BT12 6AF Rachaidh ceoltóirí ó Scoil Cheoil Bhaile Andarsan ar bord na T: 00 44 (0) 28 9560 9984 mbusanna ag taisteal bealaí éagsúla ó agus chuig Iarthar Bhéal E: [email protected] Feirste chun siamsa a chur ar fáil do phaisinéirí le ceol traidisiúnta W: www.feilebelfast.com na hÉireann! Urraithe ag Translink Metro agus Glider. -

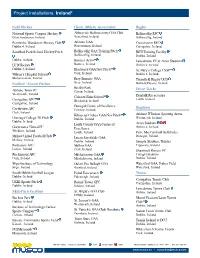

Project Installations: Ireland*

Project Installations: Ireland* Field Hockey Gaelic Athletic Association Rugby National Sports Campus Hockey Abbeyside Ballinacourty GAA Club Ballincollig RFC Blanchardstown, Ireland Waterford, Ireland Ballincollig, Ireland Pembroke Wanderers Hockey Club Athlone GAA Crosshaven RFC Dublin 4, Ireland Roscommon, Ireland Carrigaline, Ireland Sandford Park School Hockey Pitch Ballincollig GAA Training Pitch IRFU Training Facility Ballincollig, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Banteer Astro** Lansdowne FC at Aviva Stadium UCD Hockey Banteer, Ireland Dublin 4, Ireland Dublin 4, Ireland Blackrock GAA New Pitch** St. Mary’s College CSSP** Wilson’s Hospital School Cork, Ireland Dublin 6, Ireland Multyfarnham, Ireland Bray Emmets GAA Thornfield Rugby UCD Bray, Ireland Belfield Downs, Ireland Football / Soccer Pitches Breffni Park Horse Tracks Athlone Town FC Cavan, Ireland Westmeath, Ireland Colaiste Eoin School** Dundalk Racecourse Carrigaline AFC** Blackrock, Ireland Louth, Ireland Carrigaline, Ireland Donegal Centre of Excellence Stadiums Castleview AFC Convoy, Ireland Cork, Ireland Kilmacud Crokes GAA New Pitch** Athl one IT Indoor Sporting Arena Gonzaga College 3G Pitch Dublin, Ireland Westmeath, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Louth County GAA Centre of Aviva Stadium Greystones United FC Excellence Dublin 4, Ireland Wicklow, Ireland Louth, Ireland Pairc MacCumhaill Ballybofey Mallow United Football Club Lucan Sarsfields GAA Donegal, Ireland Mallow, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Semple Stadium, Thurles Portlaoise AFC Mallow GAA Tipperary, Ireland Laoise, Ireland Cork, Ireland Shamrock Rovers FC Rockmount AFC Mitchelstown GAA Tallaght Stadium Cork, Ireland Mitchelstown, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Sligo Institute of Technology Oulart The Ballagh GAA Waterford GAA, Fraher Field Sligo, Ireland Wexford, Ireland Waterford, Ireland South Dublin Football League Pobal Eascarrach Tennis Dublin, Ireland Falcarragh, Ireland Carrigaline Tennis Club UKBL Sports Pitch Round Tower GFC Carrigaline, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Kildare, Ireland Lansdowne Tennis Club Multi-Pitch Facilities St.