Remaking Homosociality and Masculinity in Fan Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Fanfic in Negotiation: Livejournal, Archive of Our Own, and the Affordances of Read-Write Platforms

Digital fanfic in negotiation: LiveJournal, Archive of our Own, and the affordances of read-write platforms. Introduction Fanfiction is the unauthorized rewriting or adaptation of popular media narratives, utilizing corporately owned characters, settings and storylines to tell an individual writer’s own story (self-ref, 2017). It is often abbreviated to fanfic or even fic, and exists in a thoroughly grey legal area between copyright infringement and fair use (Tushnet 1997, McCardle 2011). Though there were a few cases of cease-and-desist letters sent to fan writers in the twentieth century, media corporations now understand it is useless to attempt to prosecute fanfic writers – for one thing, there are simply too many of us,1 and for another it would be terrible publicity. Though modern fanfic can be reliably dated to the 1960s (Jenkins 1992), it is now primarily an online practice, and the fastest growing form of writing in the world (self ref). This paper uses participant observation and online ethnography to explore how fanfiction archives utilize digital affordances. Following Murray, I will argue that a robust understanding of digital read-write platforms needs to account for the social and legal context of digital fiction as well as its technological affordances. Whilst the online platform LiveJournal in some ways channels user creativity towards a more self-evidentially ‘digital’ texts than its successor in the Archive of Our Own (A03), the Archive encourages greater reader interactivity at the level of archive and sorting. I will demonstrate that in some ways, the A03 recoups some of the cultural capital and use value of print. -

* White House Discloses Another Tape Missing

* White House discloses another tape missing .AlifnuCTO ; (AP)--The White House disclosed in court Wednesday that an 18-minute segment is missing from vet another subpoenaed -roidential atergate tape, and the ludge suggested all the subpoenaed material be placed in the courts custody. Chief U.S. District Court Judge John J. Firin; suggested that the whitee House voluntarily turn over custody of the tapes. If it does not, he said the special Watergate prosecutor should issue a subpoena. "ft is not because the court doesn't trust the hite ,Ouse," 4ric i said, but added, "This is another instance that convinces the court to take custody." white H!oue lawyer J. "red. .;shwrdt said the 1.8-ninute lapse in the tape was discovered only Tuesday evening on a tape recording made June 20, 1972. !reviouslv the "hite House had disclosed that a four- minute telephone conversation on that date between President Nixon and then Attorne. General John N. Mitch- ell xent unrecorded. The other June 20 tae made on the automatic White house e recording epuinment as1 a two-and-a-half hour face-to-Face conversation between the President and aides H.R. Haldeman and John 1). Fhrlichman. They talked with Nixon short]- after they not with then Counsel John W. Dean I.I, itchell and others. Cuzhardt said the lansed 1.8 minutes are recorded only as an audible tone and no conversations can be heard. The two tanes were cut three da-s after the June 17, 1972, breab-in of Democratic Party hea'iuartors in the Uatergate Office Buildin !. -

Audiences, Gender and Community in Fan Vidding Katharina M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2011 "Veni, Vidi, Vids!" audiences, gender and community in Fan Vidding Katharina M. Freund University of Wollongong, [email protected] Recommended Citation Freund, Katharina M., "Veni, Vidi, Vids!" audiences, gender and community in Fan Vidding, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications, Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, 2011. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3447 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] “Veni, Vidi, Vids!”: Audiences, Gender and Community in Fan Vidding A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy From University of Wollongong by Katharina Freund (BA Hons) School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications 2011 CERTIFICATION I, Katharina Freund, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Arts Faculty, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Katharina Freund 30 September, 2011 i ABSTRACT This thesis documents and analyses the contemporary community of (mostly) female fan video editors, known as vidders, through a triangulated, ethnographic study. It provides historical and contextual background for the development of the vidding community, and explores the role of agency among this specialised audience community. Utilising semiotic theory, it offers a theoretical language for understanding the structure and function of remix videos. -

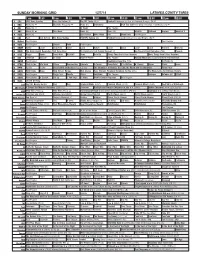

Sunday Morning Grid 12/7/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/7/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Swimming PGA Tour Golf Hero World Challenge, Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Wildlife Outback Explore World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Indianapolis Colts at Cleveland Browns. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR The Omni Health Revolution With Tana Amen Dr. Fuhrman’s End Dieting Forever! Å Joy Bauer’s Food Remedies (TVG) Deepak 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Holiday Heist (2011) Lacey Chabert, Rick Malambri. 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 (2011) (G) The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Fútbol MLS 50 KOCE Wild Kratts Maya Rick Steves’ Europe Rick Steves Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) The Roosevelts: An Intimate History 52 KVEA Paid Program Raggs New. -

Winter 2003 Vol. 26 No. 1 College of Arts & Sciences

WINTER 2003 VOL. 26 NO. 1 COLLEGE OF ARTS & SCIENCES Dean Kumble R. Subbaswamy Executive Associate Dean David Zaret Associate Dean for Research and Infrastructure Ted Widlanski Associate Dean for Undergraduate Education Linda Smith Associate Dean for Program Development and Graduate Education Michael McGerr Executive Director of Development/Alumni Programming Tom Herbert Managing Editor Anne Kibbler COLLEGE OF ARTS & SCIENCES ALUMNI ASSOCIATION BOARD President Martha A. Tardy, BA’56 Vice President Kathryn Ann Krueger, M.D., BA’80 Secretary/Treasurer Dan M. Cougill, BA’75, MBA’77 Executive Council Representative THE COLLEGE OF ARTS & SCIENCES OFFERS THESE AREAS OF STUDY: James M. Rogers, BS’56 African Studies History & Philosophy of Science BOARD MEMBERS African-American and African Diaspora Studies India Studies Animal Behavior Individualized Major Program Ann M. Anderson, BA’87 Anthropology Information Technology John E. Burks Jr., PhD’79 Apparel Merchandising Interior Design Douglas G. Dayhoff, BA’92 Astronomy & Astrophysics International Studies Lisa A. Marchal, BA'96 Audiology & Hearing Science Italian John D. Papageorge, BA’89 Biochemistry Jewish Studies Dan Peterson, BS’84 Biology Latin American & Caribbean Studies Sheila M. Schroeder, BA’83 Central Eurasian Studies Liberal Arts & Management Chemistry Linguistics Janet S. Smith, BA’67 Classical Civilization Mathematics Alan Spears, BA’79, MPA’81, JD’90 Classical Studies Medieval Studies Frank Violi, BA’80 Cognitive Science Microbiology William V. West, BA’96 Communication & Culture -

Masculinity, Homosociality, and Violence Among Fraternity Men

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Honors Scholar Theses Honors Scholar Program Spring 5-1-2020 Brothers as Men: Masculinity, Homosociality, and Violence Among Fraternity Men Daniel McCloskey [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation McCloskey, Daniel, "Brothers as Men: Masculinity, Homosociality, and Violence Among Fraternity Men" (2020). Honors Scholar Theses. 717. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses/717 Brothers as Men: Masculinity, Homosociality, and Violence Among Fraternity Men by Daniel T. McCloskey Honors Thesis and University Scholar Project Department of Anthropology University of Connecticut University Scholar Committee: Dr. Françoise Dussart, Chair Dr. Pamela Erickson Dr. Daisy Reyes Honors Advisor: Dr. Alexia Smith May 2020 McCloskey, 2020 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 3 Chapter 1: Introduction 5 Chapter 2: Gender 14 Chapter 3: Masculinity 25 Chapter 4: Homosociality 43 Chapter 5: Violence 61 Chapter 6: Conclusions 78 Bibliography 82 Appendices 86 McCloskey, 2020 3 Acknowledgements As much as I have dedicated my time and energies to this thesis, this work would not have been possible without the insight and guidance of so many people including my committee, my professors, programs at the University of Connecticut, my friends, and my family. While there are not words in the English language to fully express my appreciation and gratitude to these individuals, I will now do my best to make an attempt. First and foremost, I must acknowledge the role of the committee that helped me through this project. I would like to thank Dr. Françoise Dussart for her guidance throughout this process. -

Prosociality and a Sociosexual Hypothesis for the Evolution of Same-Sex Attraction in Humans

fpsyg-10-02955 January 10, 2020 Time: 9:34 # 1 PERSPECTIVE published: 16 January 2020 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02955 Prosociality and a Sociosexual Hypothesis for the Evolution of Same-Sex Attraction in Humans Andrew B. Barron1* and Brian Hare2 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2 Department of Evolutionary Anthropology, Center for Cognitive Science, Duke University, Durham, NC, United States Human same-sex sexual attraction (SSSA) has long been considered to be an evolutionary puzzle. The trait is clearly biological: it is widespread and has a strong additive genetic basis, but how SSSA has evolved remains a subject of debate. Of itself, homosexual sexual behavior will not yield offspring, and consequently individuals expressing strong SSSA that are mostly or exclusively homosexual are presumed to have lower fitness and reproductive success. How then did the trait evolve, and how is it maintained in populations? Here we develop a novel argument for the evolution of SSSA that focuses on the likely adaptive social consequences of SSSA. We argue that same sex sexual attraction evolved as just one of a suite of traits responding to strong selection for ease of social integration or prosocial behavior. A strong driver of Edited by: recent human behavioral evolution has been selection for reduced reactive aggression, Antonio Benítez-Burraco, University of Seville, Spain increased social affiliation, social communication, and ease of social integration. In many Reviewed by: prosocial mammals sex has adopted new social functions in contexts of social bonding, Jaroslava Varella Valentova, social reinforcement, appeasement, and play. We argue that for humans the social University of São Paulo, Brazil Rafael Lucas Rodriguez, functions and benefits of sex apply to same-sex sexual behavior as well as heterosexual University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, behavior. -

': the Making and Mauling of Churchill's People (BBC1, 1974-75)

Williams J, Greaves I. ‘Must We Wait 'til Doomsday?’: The Making and Mauling of Churchill's People (BBC1, 1974-75). Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 2017, 37(1), 82-95 Copyright: This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television on 19th April 2017, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/01439685.2016.1272804 DOI link to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01439685.2016.1272804 Date deposited: 31/12/2016 Embargo release date: 19 October 2018 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk ‘MUST WE WAIT 'TIL DOOMSDAY?’: THE MAKING AND MAULING OF CHURCHILL’S PEOPLE (BBC1, 1974-75) Ian Greaves and John Williams Correspondence: John Williams, 12 Queens Road, Whitley Bay NE26 3BJ, UK. E-mail: [email protected] In 1974, the lofty ambition of a BBC drama producer to manufacture a ‘prestige’ international hit along the lines of Elizabeth R (BBC2, 1971) came unstuck. In this case study, the authors consider the plight of Churchill’s People (BBC1, 1974-75) during a time of economic strife in the UK and industrial unrest at the BBC, and ask how a series which combined so many skilled writers, directors and actors could result in such a poorly-received end product. Churchill’s People is also placed in a wider context to assess its ‘neglected’ status, the authors drawing parallels with other historical drama of the era. The series’ qualification for being ‘forgotten’ is considered in relation to its struggle in the ratings against strong competition, the ‘blacking out’ by unions of production at the BBC for eight weeks and the subsequent pressures on transmission times, prompting the authors’ consideration of a more qualified definition of ‘lost’ drama, i.e. -

How Harry Potter Became the Boy Who Lived Forever

12/17/12 How Harry Potter Became the Boy Who Lived Forever ‑‑ Printout ‑‑ TIME Back to Article Click to Print Thursday, Jul. 07, 2011 The Boy Who Lived Forever By Lev Grossman J.K. Rowling probably isn't going to write any more Harry Potter books. That doesn't mean there won't be any more. It just means they won't be written by J.K. Rowling. Instead they'll be written by people like Racheline Maltese. Maltese is 38. She's an actor and a professional writer — journalism, cultural criticism, fiction, poetry. She describes herself as queer. She lives in New York City. She's a fan of Harry Potter. Sometimes she writes stories about Harry and the other characters from the Potterverse and posts them online for free. "For me, it's sort of like an acting or improvisation exercise," Maltese says. "You have known characters. You apply a set of given circumstances to them. Then you wait and see what happens." (See a Harry Potter primer.) Maltese is a writer of fan fiction: stories and novels that make use of the characters and settings from other people's professional creative work. Fan fiction is what literature might look like if it were reinvented from scratch after a nuclear apocalypse by a band of brilliant pop-culture junkies trapped in a sealed bunker. They don't do it for money. That's not what it's about. The writers write it and put it up online just for the satisfaction. They're fans, but they're not silent, couchbound consumers of media. -

How Existing Social Norms Can Help Shape the Next Generation of User-Generated Content

Everything I Need To Know I Learned from Fandom: How Existing Social Norms Can Help Shape the Next Generation of User-Generated Content ABSTRACT With the growing popularity of YouTube and other platforms for user-generated content, such as blogs and wikis, copyright holders are increasingly concerned about potential infringing uses of their content. However, when enforcing their copyrights, owners often do not distinguish between direct piracy, such as uploading an entire episode of a television show, and transformative works, such as a fan-made video that incorporates clips from a television show. The line can be a difficult one to draw. However, there is at least one source of user- generated content that has existed for decades and that clearly differentiates itself from piracy: fandom and “fan fiction” writers. This note traces the history of fan communities and the copyright issues associated with fiction that borrows characters and settings that the fan-author did not create. The author discusses established social norms within these communities that developed to deal with copyright issues, such as requirements for non-commercial use and attribution, and how these norms track to Creative Commons licenses. The author argues that widespread use of these licenses, granting copyrighted works “some rights reserved” instead of “all rights reserved,” would allow copyright holders to give their consumers some creative freedom in creating transformative works, while maintaining the control needed to combat piracy. However, the author also suggests a more immediate solution: copyright holders, in making decisions concerning copyright enforcement, should consider using the norms associated with established user-generated content communities as a framework for drawing a line between transformative work and piracy. -

The Role of Chivalry in Medieval and Modern Society Grace M

HUMANITIES All Roads Lead to Homosociality: The Role of Chivalry in Medieval and Modern Society Grace M. McDougall Faculty Mentor: Dr. Karma Lochrie, Department of English, Indiana University Bloomington ABSTRACT This paper examines the role of chivalry in Marie de France’s lais, focusing on Guigemar with support from Bisclavret. One of the most-studied authors of the medieval period, Marie de France channels the values, anxieties, and societal dynamics of her time by both adhering to and pushing against literary norms. Guigemar and Bisclavret present near-perfect examples of knighthood according to chivalric norms, save for two flaws: Guigemar has no love for women, and Bisclavret is a werewolf. The treatment of these knights and their peculiarities reveals the strict expectations of masculinity and the risks of breaking from them. I pay particular attention to the importance of humility in chivalric masculinity and the ways in which their peculiarities affect their relationships, especially with other men. Guigemar shows that humility, rather than courage, martial skill, or courtesy, was the most important chivalric value. Humility is so essential because the main role of chivalry was to preserve the relationships between men that formed the basis of medieval society. I argue that understanding the cultural history of chivalry is important for modern audiences because the concept of chivalry is still used by many groups to legitimize and promote their interests and continues to shape our perceptions of masculinity and gender dynamics. While what we think of chivalry has changed greatly since Marie de France’s time, the ends of chivalry remain the same—to promote the interests of those in positions of power. -

An Exploration of Female and Male Homosocial Bonds in DH Lawrence's

Student ID: 200614777 ENGL3318: Final Year Project 2014/15 Dr Fiona Becket An exploration of female and male homosocial bonds in D. H. Lawrence’s ‘serious English novels’ ENGL 3318: Final Year Project Tutor: Dr Fiona Becket Student ID: 200614777 1 Student ID: 200614777 ENGL3318: Final Year Project 2014/15 Dr Fiona Becket Introduction………………………………………………………………… 3 I. Female Homosociality in The Rainbow………………………… 4 II. Female Homosociality in Women in Love……………………… 9 III. Male Homosociality in Women in Love………………………… 15 IV. Male Homosociality in Aaron’s Rod……………………………. 20 Conclusion………………………………………………………………….. 25 Bibliography………………………………………………………………… 26 2 Student ID: 200614777 ENGL3318: Final Year Project 2014/15 Dr Fiona Becket Introduction To focus exclusively on homosocial relationships, ‘the social bonds between persons of the same sex’, may seem like an odd choice when studying a writer like D. H. Lawrence.1 Lawrence himself stated that ‘The great relationship, for humanity, will always be the relation between man and woman. The relation between man and man, woman and woman, parent and child, will always be subsidiary.’2 His attitude towards sex, gender and the nature and importance of homosocial relationships, however, were subject to many changes throughout his career. These changes, I argue, are most visible in three closely related novels written across a seven-year span. The first is the female-focused narrative of The Rainbow, banned for obscenity upon publication due to its protagonist’s lesbian affair.3 The second is its sequel, Women in Love, best-known for the ambiguous relationship between its male protagonists, but whose female relationships are also worth studying. The last novel is Aaron’s Rod, a text in which the titular protagonist relinquishes his ties to his family and country and explores the possibilities of bonds with other men.