Revisiting Overton Park: Political and Judicial Controls Over Administrative Actions Affecting the Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birding at T. O. Fuller and Nearby Areas

Birds of T. O. Fuller State Park 1500 Mitchell Road, Memphis, Tennessee 38109 / 901-543-7581 T.O. Fuller State Park occurs on a bluff overlooking the floodplain of the Mississippi River. Lying in the heart of the Mississippi Flyway, the park offers great opportunities to see migrating birds in the spring and fall. Look for warblers, vireos, thrushes and flycatchers along the eight miles of park trails and along forest edges. A new wildlife enhancement area containing four miles of paved trails is under development and will consist of floodplain wetlands, wildflower valleys, native grassy meadows, and upland ponds. The area has already attracted rare black-bellied whistling ducks, and nesting black-necked stilts. TO Fuller now has 140 species of birds observed. Responsible Birding - Do not endanger the welfare of birds. - Tread lightly and respect bird habitat. - Silence is golden. - Do not use electronic sound devices to attract birds during nesting season, May-July. - Take extra care when in a nesting area. - Always respect the law and the rights of others, violators subject to prosecution. - Do not trespass on private property. - Avoid pointing your binoculars at other people or their homes. - Limit group sizes in areas that are not conducive to large crowds. Helpful Links Tennessee Birding Trails www.tnbirdingtrail.org Field Checklist of Tennessee Birds www.tnwatchablewildlife.org eBird Hotspots and Sightings www.ebird.org www.tnstateparks.com Tennessee Ornithological Society www.tnbirds.org Indigo Bunting Tennessee State Parks Birding -

Overton Park Court Apartments View the Final National Register Nomination

United States Department of the Interior National Register Listed National Park Service 6/28/2021 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form MP100006712 This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name Overton Park Court Apartments Other names/site number Park Lane Apartments Name of related multiple property listing Historic Residential Resources of Memphis, Shelby County, TN 2. Location Street & Number: 2095 Poplar Avenue City or town: Memphis State: TN County: Shelby Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: N/A Zip: 38104_________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __X_ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide X local Applicable National Register Criteria: X A B X C D Signature of certifying official/Title: Date Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer, Tennessee Historical Commission State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Memphis Zoo: the Memphis Zoo, Located in Midtown Memphis, Tennessee, Is Home to More Than 3,500 Animals Representing Over 500 Different Species

Memphis Zoo: The Memphis Zoo, located in Midtown Memphis, Tennessee, is home to more than 3,500 animals representing over 500 different species. Created in April 1906, the zoo has been a major tenant of Overton Park for more than 100 years. The land currently designated to the Memphis Zoo was defined by the Overton Park master plan in 1988, it is owned by the City of Memphis. Adults (12-59) $15, Parking $5; 9am-5pm. www.memphiszoo.org National Civil Rights Museum: The National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee, USA, was built around the former Lorraine Motel at 450 Mulberry Street, where Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated on April 4 1968. The Lorraine Motel remained open following King's assassination until it was foreclosed in 1982. Adults $12, Child (4-17) $ 8.50; 9am-5pm. www.civilrightsmuseum.org Incredible Pizza: Great Food, Fun, Family and Friends! A huge buffet, 4 cool dining rooms, indoor Go-Karts, Bumper Cars, Arcade, and much more! Wednesday 11am- 8:30pm, Friday-Sunday 11am-10pm. www.incrediblepizza.com Laser Quest: is great family fun and entertainment, perfect for birthday parties and youth group events. Youth group packages, Prices vary according to group size. Wednesday 6pm- 9pm, Friday-Saturday 4-11pm. www.laserquest.com Putt-Putt: Family Entertainment Center, Laser Tag Arena, Driving Range, Batting Cages, Go Karts, Bumper Boats, Ropes Course, Miniature Golf, Arcade, Birthday Parties, Corporate Events, Lock-In, School Groups. Indoor activities open at 8am, Outdoor activities begin at 4pm. Groups 15 or more call 901-338-5314. www.golfandgamesmemphis.com Overton Park: Overton Park is a large, 342-acre public park in Midtown Memphis, Tennessee. -

Of Memphis and Memphis Land Other Incentives Available to Companies May 16-May 22 Bank Officials Formally Opened Fairway That Hire Veterans Will Be Available

May 16-22, 2014, Vol.7, Issue 21 REHABBING VOLVO BUILDING IN MEMPHIS CENTER IN MISS. Right-handed pitcher The Volvo Group Jason Motte is using his »will build a rehab assignment with 1 million-square-foot the Memphis Redbirds distribution center in to regain his pre- Byhalia that should Tommy John surgery employ around 250. Its form for the St. Louis expected completion is Cardinals. • P. 2 2 the end of 2014. • P. 1 3 SHELBY • FAYEttE • TiptON • MadisON CULTURE OF HEALTH MBGH encouraging local companies to promote wellness in workplace P. 1 6 Medtronic employees Jeremy Tincher, left, and Craig Squires jog along a 2-mile path around the perimeter of the company's Memphis campus during their lunch break. (Memphis News/Andrew J. Breig) LAND GRAB AT GROWING WITH OVERTON PARK TECHNOLOGY Midtown park’s Michael Hatcher’s greensward usage landscaping firm has conflict sparks call for always embraced garage. • P. 1 8 technology. • P. 1 2 DIGEST: PAGE 2 | INKED/RECAP: PAGE 8 | FINANCIAL SERVICES: PAGE 11 | NEWSMAKERS: PAGE 21 | EDITORIAL: PAGE 30 A Publication of The Daily News Publishing Co. | www.thememphisnews.com 2 May 16-22, 2014 www.thememphisnews.com weekly digest Get news daily from The Daily News, www.memphisdailynews.com. Fairway Manor THE MEMPHIS NEWS | almanac can have on leadership, accountability and Development Opens revenue. Information about tax credits and City of Memphis and Memphis Land other incentives available to companies MAY 16-MAY 22 Bank officials formally opened Fairway that hire veterans will be available. This week in Memphis history: Manor Thursday, May 15, in southwest Cliff Yager, founder and managing Memphis. -

Saul Brown Photograph Collection

Saul Brown Photograph Collection Memphis Public Library and Information Center Memphis and Shelby County Room Collection processed by Emily Baker with special thanks to Wayne Dowdy and Gina Cordell 2010 1 Saul Brown Biography 3 Scope and Provenance 3 Contents Summary 4 Detailed Finding Aid 6 Name Index 109 2 Saul Brown Biography Saul Brown was born in 1910 in New York to Russian immigrants. As a young adult, Brown attended Tech High School in Memphis and graduated from the Memphis Academy of Fine Arts with a degree in Fine Art. Brown served in the Air Force during World War II. After graduation, he found work with Loew’s Theaters, where he created publicity displays. Brown worked as a staff photographer for the Memphis Press-Scimitar for twenty years, retiring in April of 1980 as the newspaper’s chief photographer. After retirement, Brown continued taking publicity photographs for various Memphis theaters as well as images of public figures, personal friends, and Memphis and its residents. He received the Freedom Foundation Award in 1972. In 1986, Brown donated $5,000 to Memphis State University to establish the Saul Brown/Memphis Press Scimitar Award, awarded to students in news journalism and news photography beginning in the 1987-1988 academic year. In 1987, due to his financial support of the school’s academic fund, Brown was granted membership in the school’s Presidents Club. Saul Brown passed away in Memphis on March 13, 1992 at the home of Myron Taylor, the brother of Mildred, his late wife. Scope and Provenance The Saul Brown Photograph Collection was donated to the Memphis Public Library and Information Center in 2007. -

Historic Sites*

*Descriptions and photographsofthesitesappear onthefollowingpages. 480 Hancock Sullivan Johnson Pickett Clay Claiborne Macon Hawkins n to Scott Campbell g Stewart Montgomery Robertson Sumner in e Fentress h Carter al Grainger s ousd Jackson Overton Union n a C Tr ble i he am Greene W o Lake Obion Henry ath H ic Weakley Houston am Smith n Anderson U Wilson Putnam Morgan Jefferson Dickson Davidson Benton Cocke Selected Tennessee Historic Sites* Dyer Humphreys DeKalb Cumberland Gibson Carroll White Williamson Roane n Sevier le Rutherford Cannon do da u r Hickman n Lo Blount de Crockett re au Warren n Bu L Henderson Va Bledsoe Madison Perry Maury Rhea S Haywood e s Monroe Decatur Lewis Bedford Coffee q ig u e McMinn Tipton Grundy at Chester ch M Marshall ie Moore Bradley TENNESSEE BLUEBOOK Fayette Hardeman Wayne Lawrence Giles Hamilton Shelby McNairy Hardin Polk Lincoln Franklin Marion 1. Victorian Village, Memphis 19. Mansker's Station & Bowen-Campbell House, 2. Hunt/Phelan House, Memphis Goodlettsville 3. Graceland, Memphis 20. Jack Daniel's Distillery, Lynchburg 4. Chucalissa Prehistoric Indian Village, Memphis 21. Cordell Hull Birthplace and Museum, Byrdstown 5. Beale Street Historic District, Memphis 22. Chickamauga/Chattanooga National Military Park, 6. Alex Haley Home and Museum, Henning Chattanooga 7. Reelfoot Lake, Tiptonville 23. Rhea County Courthouse, Dayton 8. Ames Plantation, Grand Junction 24. York Grist Mill/Home of Alvin C. York, Pall Mall 9. Pinson Mounds State Park, Pinson 25. Rugby 10. Shiloh National Military Park, Shiloh 26. The Graphite Reactor (X-10) at Oak Ridge National 11. Natchez Trace Parkway, Hohenwald Laboratory, Oak Ridge 12. -

The Fvnr!RGREENEWS

THE BURHOW LIBRARY The FVnr!RGREENEWS A A'eiglt!Jorltood Newspaper Sponsored b!J f/ollintine- Evergreen Community Action Association of the newcomers obtained a state charter in 1892 for the Baron Hirsch Benevolent Society in honor of this Jewish philanthropist. The name stuck and the history of the Hirseh History pre sent Baron Hirsch congregation dates back to this period. by Rick Thomas The congregation had 50 members in 1900 and most of its activity was still centered downtown. However, new immigrants, mostly from R us s i a, soon made the synagogue too small. Consequently, a new building was built in 1914 at Washington and 4th. Although the size of the community varied during the next decades, mem bership surpassed 500 families in 1941. Again the con gregation outgrew the synagogue and many members moved to what is now the mid-town area (including the V/B community). To many people, the growing membership and chang ing residential patterns offered an opportunity to build a magnificent temple. In 1945, the 1 and at Vollentine and Evergreen was purchased for $20,000 and two ad joining lots were later bought for $27,750. An architect was retained in 1946 and WILLIAM GERBER supervised initial planning. PHILIP BELZ oversaw the final stages. In 1952 the educational building was completed and in 1955 ground was broken for a new synagogue. The cornerstone was a block of Jerusalem marble and mixed with the mortar was a sack of earth brought here from Mt. Zion. Today Baron Hirsch has a congregation of over 15 00 members of which about a third live in the V/E com munity. -

Memphis Voices: Oral Histories on Race Relations, Civil Rights, and Politics

Memphis Voices: Oral Histories on Race Relations, Civil Rights, and Politics By Elizabeth Gritter New Albany, Indiana: Elizabeth Gritter Publishing 2016 Copyright 2016 1 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………..3 Chapter 1: The Civil Rights Struggle in Memphis in the 1950s………………………………21 Chapter 2: “The Ballot as the Voice of the People”: The Volunteer Ticket Campaign of 1959……………………………………………………………………………..67 Chapter 3: Direct-Action Efforts from 1960 to 1962………………………………………….105 Chapter 4: Formal Political Efforts from 1960 to 1963………………………………………..151 Chapter 5: Civil Rights Developments from 1962 to 1969……………………………………195 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………..245 Appendix: Brief Biographies of Interview Subjects…………………………………………..275 Selected Bibliography………………………………………………………………………….281 2 Introduction In 2015, the nation commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the Voting Rights Act, which enabled the majority of eligible African Americans in the South to be able to vote and led to the rise of black elected officials in the region. Recent years also have seen the marking of the 50th anniversary of both the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed discrimination in public accommodations and employment, and Freedom Summer, when black and white college students journeyed to Mississippi to wage voting rights campaigns there. Yet, in Memphis, Tennessee, African Americans historically faced few barriers to voting. While black southerners elsewhere were killed and harassed for trying to exert their right to vote, black Memphians could vote and used that right as a tool to advance civil rights. Throughout the 1900s, they held the balance of power in elections, ran black candidates for political office, and engaged in voter registration campaigns. Black Memphians in 1964 elected the first black state legislator in Tennessee since the late nineteenth century. -

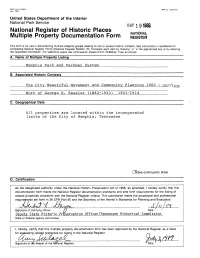

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER

NFS Form 10-900-b QMB No 1024-0018 (Jan 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bufietin 16). Compfete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing _____Memphis Park and Parkway System__________________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts _____The City Beautiful Movement and Community Planning 1900 - 1977/1,939 Work of George E. Kessler (1862-1923) "1901-1914 C. Geographical Data All properties are located within the incorporated limits of the City of Memphis, Tennessee See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. Signature of certifying official f Date •' Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer/Tennessee Historical Commission State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

CONCEPT MAP Concept for a Regional Network of Connected Green Infrastructure

MID-SOUTH REGIONAL GREENPRINT CONCEPT MAP Concept for a Regional Network of Connected Green Infrastructure Mississippi River Trail (MRT) TIPTON continues north COUNTY T E N N E S S E E TIPTON COUNTY To Hatchie River and MASON Dyersburg To Covington To Hatchie River Orgill 50 Park 25 Wapanocca National Wildlife Refuge BRADEN Meeman-Shelby MILLINGTON Forest State Park 2 45 23 44 A R K A N S A S GALLAWAY 14 To Wapanocca 15 31 24 ARLINGTON To Somerville Eagle 11 CRITTENDEN Lake Refuge COUNTY 15 Firestone 36 Park Davy 12 5 Crockett SUNSET 37 Park 53 38 Nesbit Park 12 MARION 6 To Oakland LAKELAND 16 BARTLETT 1 13 24 31 JFK Park FAYETTE Mississippi 8 Greenbelt 27 COUNTY Park Tilden 3 5 Rodgers 1 10 35 Park 25 28 WEST Mud Island 26 54 MEMPHIS Park 20 Overton Park Tom Lee 20 SHELBY To Forrest City 30 Shelby Farms Park Park COUNTY 17 MEMPHIS 2 Herb Parsons Lake 47 State Park Presidents 8 46 Island 17 14 Audubon Park 40 34 MLK Riverside 6 33 Park 22 16 30 To Marianna r 29 Mississippi River 13 Trail (MRT) e 18 GERMAN- continues south v 52 18 TOWN Frank Road Wolf River Wetland i 26 Park Wildlife Refuge Area 16 R 4 To Horseshoe T.O Fuller 48 Lake i 42 State Park 28 p 49 i p 39 s s COLLIER- s i 4 VILLE To Ghost M i s PIPERTON 9 River Mike Rose Soccer Complex 55 41 43 11 29 7 SOUTH- To Marshall HAVEN County 19 24 7 23 HORN OLIVE Hernando Southaven LAKE BRANCH Desoto Park Central Park MARSHALL 19 Snowden 3 35 Grove Park 32 Wooten Olive Branch COUNTY Park 27 City Park WALLS Horseshoe Lake 10 57 56 34 DESOTO To Holly COUNTY58 51 Springs Key On-Street Connectors -

Wise and Wild Wednesdays Elk Creature Feature Panda News

New Event — Wise and Wild Wednesdays Elk Creature Feature March / April 2009 Panda News PUBLISHED FOR FRIENDS OF THE ME mp HIS ZOO EXZOO- BERANCE! JILL MAYBRY Exzooberance™ is a bimonthly Memphis Zoological Society publication providing information for friends of the Memphis Zoo. Send comments to MZS, 2000 Prentiss Place, 3 4 Memphis, TN 38112, call (901) 276-WILD or log onto www.memphiszoo.org. Vol. XVIII, No. 2 Memphis Zoological Society Board of Directors as of December 2008 Officers: Carol W. Prentiss, Chair Kelly Truitt, Vice Chair Gene Holcomb, Treasurer Joseph C. DeWane, M.D., Secretary MidSouth Chevy Directors: full page ad F. Norfleet Abston Karl A. Schledwitz Robert A. Cox Lucy Shaw Thomas C. Richard C. Shaw Farnsworth, III Diane Smith Diana Hull Brooke Sparks Henry A. Hutton John W. Stokes, Jr. Dorothy Kirsch Steven Underwood Robert C. Lanier Joe Warren Joyce A. Mollerup Robin P. Watson Jason Rothschild Russell T. Wigginton, Jr. Honorary Lifetime Directors: Donna K. Fisher Roger T. Knox, President Emeritus Scott P. Ledbetter Frank M. Norfleet Senator James R. Sasser Rebecca Webb Wilson Ex Officio: Dr. Chuck Brady, Zoo President & CEO Pete Aviotti, Jr., Special Assistant to Mayor In this issue: Departments: Bill Morrison, City Council Representative Nora Fernandez, Docent/Volunteer Representative 3 Creature Feature: Elk 4 Spot You at the Zoo Credits: Abbey Dane, Editor / Writer Brian Carter, Managing Editor As we get closer to the grand opening of Teton 7 Education Programs Geri Meltzer, Art Director Trek this fall, continue learning about the Jennifer Coleman, Copy Editor Toof Printing, Printer animals that will call this exhibit home. -

Memphis Downtown

328000 328000 . ADINA HOLLAND DELRAY BERRY OAKCREST THISTLE TERRACE NEW D P OINT AVE. ST. AUDUBON CORNING TWIN ST. BATTLEFIELD DALE WINDY GAP DR. CV. RESTBROOK DR. WINNIE AVE. ST. R ADINA WINDY ST. LIE ST. ST. RD. ST. DR. RD. RD. RIDGE BURNHAM DR. GIL- DR. DR. DR. ST. DR. SUN ST. BEL- LEAU S. BROWNS- CARD- CIR. DR. AVE. DR. TRAIL ST. HAWKINS DR. ST. RESTBROOK MEADE DR. ELMO ST. AVE. SOC- ST. BROOKVIEW FORTNER CV. SCRAPE ST. ORRO ELMO CV. FRED- ST. LOCK ONIA LONGMONT BATTLE- MADDOX TWIN E AVE. LAKES HALLVIEW AVE. VILLE CV. INAL 3 DR. DR. AVE. ST. CV. L CV. DR. FALCON THISTLE- CV. C CELESTE AVE. DR. L DR. RIDGE KNOLL WMPS DR. DR. HWY. VALLEY BAY RD. I NORDSTROM FIELD DR. 204 N CV. CV. RIVER ST. ALPENA DR. DR. CLAIRE ST. SU NGROVE FELIPE LN. V E GRASSY HILL FLOYD CEDELL CORNING RD. EVANGELICAL RD. LN. CV. AVE. LN. DR. ST. LN. S POINT DR. COLEMAN G NAYLOR AVE. FLOYD DR. IRMA DR. LONG- DR. CV. CV. ALTURIA RD. DOVE CALL CV. N DR. DR. CV. CV. DR. WOLF CHRISTIAN RD. RIDGE FLOYD DR. E RD. SUNRISE ST. WINSTON GAYLE DR. CV. PARFET W DUMAS EARLY DORADO PRYOR DR. ST. RD. FIAT AVE. ST. MONT CV. G R AVE. DR. RD. SCHOOL RALEIGH STATION BROWNSVILLE O RD. CV. ST. N LN. R ST. CV. WESTRIDGE PIKE CLARION DR. CELESTE LINE TWIN- CV. I DOWNS B WALDEN MEADOW ST. ROAD 852000 768000 DR. P.O. L COUNTRY KNOLL CV. ST. DR.