Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy Research Paper 84 November 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cholera Risk Assessment in Kano State, Nigeria: a Historical Review, Mapping of Hotspots and Evaluation of Contextual Factors

PLOS NEGLECTED TROPICAL DISEASES RESEARCH ARTICLE The cholera risk assessment in Kano State, Nigeria: A historical review, mapping of hotspots and evaluation of contextual factors 1 2 2 2 Moise Chi NgwaID *, Chikwe Ihekweazu , Tochi OkworID , Sebastian Yennan , 2 3 4 5 Nanpring Williams , Kelly ElimianID , Nura Yahaya Karaye , Imam Wada BelloID , David A. Sack1 1 Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America, 2 Nigeria Centre for Disease Control, Abuja, Nigeria, 3 Department of a1111111111 Microbiology, University of Benin, Nigeria, 4 Department of Public Health and Disease Control, Kano State a1111111111 Ministry of Health, Kano, Nigeria, 5 Department of Public Health and Disease Control, Ministry of Health a1111111111 Kano, Kano, Nigeria a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS Nigeria is endemic for cholera since 1970, and Kano State report outbreaks annually with Citation: Ngwa MC, Ihekweazu C, Okwor T, Yennan high case fatality ratios ranging from 4.98%/2010 to 5.10%/2018 over the last decade. How- S, Williams N, Elimian K, et al. (2021) The cholera ever, interventions focused on cholera prevention and control have been hampered by a risk assessment in Kano State, Nigeria: A historical lack of understanding of hotspot Local Government Areas (LGAs) that trigger and sustain review, mapping of hotspots and evaluation of contextual factors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 15(1): yearly outbreaks. The goal of this study was to identify and categorize cholera hotspots in e0009046. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. Kano State to inform a national plan for disease control and elimination in the State. -

Downloads/14Th%20Qterly%20Final%20 Se%2024%20Oct%2012.Pdf)

Representation in REDD Responsive Forest Governance Initiative (RFGI) Research Programme The Responsive Forest Governance Initiative (RFGI) is a research and training program, focusing on environmental governance in Africa. It is jointly managed by the Council for the Development of Social Sciences Research in Africa (CODESRIA), the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign (UIUC). It is funded by the Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA). The RFGI activities are focused on 12 countries: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, DR Congo, Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda. The initiative is also training young, in-country policy researchers in order to build an Africa-wide network of environmental governance analysts. Nations worldwide have introduced decentralization reforms aspiring to make local government responsive and accountable to the needs and aspirations of citizens so as to improve equity, service delivery and resource management. Natural resources, especially forests, play an important role in these decentralizations since they provide local governments and local people with needed revenue, wealth, and subsistence. Responsive local governments can provide forest resource-dependent populations the flexibility they need to manage, adapt to and remain resilient in their changing environment. RFGI aims to enhance and help institutionalize widespread responsive and accountable local governance processes that reduce vulnerability, enhance local wellbeing, and improve forest management with a special focus on developing safeguards and guidelines to ensure fair and equitable implementation of the Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) and climate-adaptation interventions. REDD+ is a global Programme for disbursing funds, primarily to pay national governments of developing countries, to reduce forest carbon emission. -

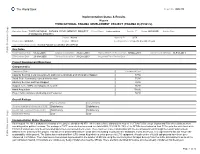

The World Bank Implementation Status & Results

The World Bank Report No: ISR4370 Implementation Status & Results Nigeria THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (FADAMA III) (P096572) Operation Name: THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 7 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: (FADAMA III) (P096572) Country: Nigeria Approval FY: 2009 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): National Fadama Coordination Office(NFCO) Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 01-Jul-2008 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date 07-Nov-2011 Last Archived ISR Date 11-Feb-2011 Effectiveness Date 23-Mar-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Capacity Building, Local Government, and Communications and Information Support 87.50 Small-Scale Community-owned Infrastructure 75.00 Advisory Services and Input Support 39.50 Support to the ADPs and Adaptive Research 36.50 Asset Acquisition 150.00 Project Administration, Monitoring and Evaluation 58.80 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Low Low Implementation Status Overview As at August 19, 2011, disbursement status of the project stands at 46.87%. All the states have disbursed to most of the FCAs/FUGs except Jigawa and Edo where disbursement was delayed for political reasons. The savings in FUEF accounts has increased to a total ofN66,133,814.76. 75% of the SFCOs have federated their FCAs up to the state level while FCAs in 8 states have only been federated up to the Local Government levels. -

Violence in Nigeria's North West

Violence in Nigeria’s North West: Rolling Back the Mayhem Africa Report N°288 | 18 May 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Community Conflicts, Criminal Gangs and Jihadists ...................................................... 5 A. Farmers and Vigilantes versus Herders and Bandits ................................................ 6 B. Criminal Violence ...................................................................................................... 9 C. Jihadist Violence ........................................................................................................ 11 III. Effects of Violence ............................................................................................................ 15 A. Humanitarian and Social Impact .............................................................................. 15 B. Economic Impact ....................................................................................................... 16 C. Impact on Overall National Security ......................................................................... 17 IV. ISWAP, the North West and -

Rural Non-Farm Income and Inequality in Nigeria

2. BACKGROUND INFORMATION, DATA AND SURVEY AREA The utilized data were collected from five different villages surveyed in rural Northern Nigeria between 2004 and 2005. These villages are situated within the Hadejia-Nguru floodplain wetlands of Jigawa state in Northern Nigeria. Data were collected from 200 households selected using a multi-stage stratified random sampling approach. The first sampling stratum was selection of the dry savanna region of northern Nigeria, which comprises six states: Sokoto, Kebbi, Zamfara, Kano, Kaduna and Jigawa. The second stratum was the selection of Jigawa state. Two important elements informed this choice. First, Jigawa state, which was carved out of Kano state in August 1991, has the highest rural population in Nigeria; about 93 percent of the state’s population dwells in rural areas3. Second, agriculture is the dominant sector of the state’s economy, providing employment for over 90 percent of the active labor force. For effective grassroots coverage of the various agricultural activities in Jigawa state, the Jigawa Agricultural and Rural Development (JARDA) is divided into four operational zones that are headquartered in the cities of Birni Kudu, Gumel, Hadejia and Kazaure. Hadejia was selected for this study, forming the third stratum of sampling. Within the Hadejia emirate, there are eight Local Government Areas (LGAs): Auyo, Birniwa, Hadejia, Kaffin-Hausa, Mallam Madori, Kaugama, Kirikasamma and Guri. Kirikasamma LGA was selected for this study, representing the fourth sampling stratum. Kirikassama LGA was specifically chosen because of the area’s intensive economic development and correspondingly higher human population compared to many other parts of Nigeria. In the fifth stratum of sampling, five villages were selected from Kirikassama LGA: Jiyan, Likori, Matarar Galadima, Turabu and Madachi. -

Preliminary Assessment of the Distribution of Large Mammals Within Idanre Forest Reserve, Ondo State, Nigeria

Awoku and Ogunjemite, 2019 Journal of Research in Forestry, Wildlife & Environment Vol. 11(4) December, 2019 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] http://www.ajol.info/index.php/jrfwe 140 jfewr ©2019 - jfewr Publications This work is licensed under a ISBN: 2141 – 1778 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Awoku and Ogunjemite, 2019 License PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF THE DISTRIBUTION OF LARGE MAMMALS WITHIN IDANRE FOREST RESERVE, ONDO STATE, NIGERIA Awoku, G. S. and Ogunjemite, B. G. Department of Ecotourism and Wildlife Management, Federal University of Technology, Akure. Corresponding Author email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The distribution of large mammals in Idanre Forest Reserve was assessed using the line transect method with a total number of five (5) transect lines and employing the use of Global Positioning System (GPS) to take the different points and location of different species of large mammals both sighted directly and indirectly. It was observed that transect C and D (within the undisturbed forest) 45 and 38 sightings respectively which were evenly distributed within this transects. It was also observed that transect C had 30.41 % the highest rate occurrence in terms of distribution of signs of large mammals. The study also revealed that in terms of vegetation cover preference, all of the large mammals were distributed with the undisturbed forest habitat while the Cephalophus silvicultor were not distributed within the disturbed forest and the farm land .Also, all the primates were available within all the habitat types with the exception of Cercocerbus torquatus which is not distributed within the Cercocebus torquatus farmland. The research revealed that there are still some significant amounts of large mammals within the reserve and if well conserved in terms of enforcement of strict adherence to forest laws, there will be an increase in terms of the distribution within their natural habitat and reduced dispersal outside their natural place of abode. -

International Journal of Arts and Humanities (IJAH) Bahir Dar- Ethiopia Vol

IJAH VOL 4 (3) SEPTEMBER, 2015 55 International Journal of Arts and Humanities (IJAH) Bahir Dar- Ethiopia Vol. 4(3), S/No 15, September, 2015:55-63 ISSN: 2225-8590 (Print) ISSN 2227-5452 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ijah.v4i3.5 The Metamorphosis of Bourgeoisie Politics in a Modern Nigerian Capitalist State Uji, Wilfred Terlumun, PhD Department of History Federal University Lafia Nasarawa State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Tel: +2347031870998 or +2348094009857 & Uhembe, Ahar Clement Department of Political Science Federal University Lafia, Nasarawa State-Nigeria Abstract The Nigerian military class turned into Bourgeoisie class has credibility problems in the Nigerian state and politics. The paper interrogates their metamorphosis and masquerading character as ploy to delay the people-oriented revolution. The just- concluded PDP party primaries and secondary elections are evidence that demands a verdict. By way of qualitative analysis of relevant secondary sources, predicated on the Marxian political approach, the paper posits that the capitalist palliatives to block the Nigerian people from freeing themselves from the shackles of poverty will soon be a Copyright ©IAARR 2015: www.afrrevjo.net Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info IJAH VOL 4 (3) SEPTEMBER, 2015 56 thing of the past. It is our argument that this situation left unchecked would create problem for Nigeria’s nascent democracy which is not allowed to go through normal party polity and electoral process. The argument of this paper is that the on-going recycling of the Nigerian military class into a bourgeois class as messiahs has a huge possibility for revolution. -

Petroleum Extraction, Agriculture and Local Communities in the Niger Delta

Petroleum Extraction, Agriculture and Local Communities in the Niger Delta. A Case of Ilaje Community. Adedayo Ladelokun Howard University Chapter I: Introduction Petroleum resource exploration and extraction-- ● A crucial economic activity ● Petroleum resources contributed substantially to economic development ● Conversely, petroleum exploration and extraction often induce negative impacts on other economic activities such as agriculture. ● Threatens environmental Safety. ● Ilaje Community,Ondo State,Nigeria, was chosen as a case study. Introduction Cont. ● Location and member states of the Niger Delta. Located in Coastal Southern Region of Nigeria. Map of the Niger Delta region Niger Delta Image of the Niger Delta Source: Ken Saro-Wiwa 20 years on Niger Delta ... Cnn.com Map of Ondo State Showing the 18 Local Government Areas Ilaje Local Government Introduction Cont. ● Population --- Estimated at 46 Million(UNDP) ● Geographical Landmark --- ND Covers area over 70,000 Sq Kilometers (ie 27,000 Miles) ● Occupation --- Farming, Fishing, Canoe Making, Trading, Net Making, and Mat Making. ● Ilaje Community --- Occupies Atlantic Coastline of Ondo State,Nigeria. ● Ilaje Local Government (Polluted Area) was one of the 18 Local Governments in Ondo State, Nigeria. ● Five Local Governments were randomly selected to served as control. Scope of the study This research work will cover Ilaje Community in Ondo State. Ondo State is located in the petroleum producing area of the Niger Delta Ilaje community was mainly into agricultural production Chapter II: Literature Review ● Agriculture in Economic Development of Nigeria: ○ Machinery for life sustenance ○ Supportive role raw material provision for industrial development ○ Todaro MP (2000) viewed role of AG as passive and supportive ○ Precondition for eco developed ○ Rapid structural transformation of the AG sector Literature Review Continues Jhingan M.L (1985) opined that: (a) AG provides food surplus for the rapidly expanding population. -

About the Contributors

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS EDITORS MARINGE, Felix is Head of Research at the School of Education and Assistant Dean for Internationalization and Partnerships in the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. With Dr Emmanuel Ojo, he was host organizer of the Higher Education Research and Policy Network (HERPNET) 10th Regional Higher Education Conference on Sustainable Transformation and Higher Education held in South Africa in September 2015. Felix has the unique experience of working in higher education in three different countries, Zimbabwe; the United Kingdom and in South Africa. Over a thirty year period, Felix has published 60 articles in scholarly journals, written and co-edited 4 books, has 15 chapters in edited books and contributed to national and international research reports. Felix is a full professor of higher education at the School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand (WSoE) specialising in research around leadership, internationalisation and globalisation in higher education. OJO, Emmanuel is lecturer at the School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. He is actively involved in higher education research. His recent publication is a co-authored book chapter focusing on young faculty in South African higher education, titled, Challenges and Opportunities for New Faculty in South African Higher Education Young Faculty in the Twenty-First Century: International Perspectives (pp. 253-283) published by the State University of New York Press (SUNY). He is on the editorial board of two international journals: Journal of Higher Education in Africa (JHEA), a CODESRIA publication and Journal of Human Behaviour in the Social Environment, a Taylor & Francis publication. -

Cooperative Agreement AID-620-A-00002

Cooperative Agreement AID-620-A-00002 Activity Summary Implementing Partner: Family Health International (FHI 360) Activity Name: Strengthening Integrated Delivery of HIV/AIDS Services (SIDHAS) Activity Objective: To sustain cross sectional integration of HIV/AIDS and TB services by building Nigerian capacity to deliver sustainable high quality, comprehensive, prevention, treatment, care and related services. This will be achieved through three key result areas: 1) Increased access to high-quality comprehensive HIV/AIDS and TB prevention, treatment, care and related services through improved efficiencies in service delivery. 2) Improved cross sectional integration of high quality HIV/AIDS and TB services 3) Improved stewardship by Nigerian institutions for the provision of high-quality comprehensive HIV/AIDS and TB services. USAID’s Assistance Objective 3 (AO 3): A sustained, effective Nigerian-led HIV/AIDS and TB response Life of Activity (start and end dates): Sept 12, 2011 – Sept 11, 2016 Report Submitted by: Phyllis Jones-Changa Submission Date: July 30, 2014 2 Table of contents Activity Summary................................................................................................................................... 2 Table of contents................................................................................................................................. 3 Acronyms and abbreviations............................................................................................................. 4 Executive Summary........................................................................................................................... -

The Case Study of Owo LGA, Ondo State, Nigeria

The International Journal Of Engineering And Science (IJES) ||Volume||2 ||Issue|| 9 ||Pages|| 19-31||2013|| ISSN(e): 2319 – 1813 ISSN(p): 2319 – 1805 Geo-Information for Urban Waste Disposal and Management: The Case Study of Owo LGA, Ondo State, Nigeria *1Dr. Michael Ajide Oyinloye and 2Modebola-Fadimine Funmilayo Tokunbo Department of Urban and Regional Planning, School of Environmental Technology, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria --------------------------------------------------------ABSTRACT-------------------------------------------------- Management of waste is a global environmental issue that requires special attention for the maintenance of quality environment. It has been observed that amount, size, nature and complexity of waste generated by man are profoundly influenced by the level of urbanization and intensity of socio-economical development in a given settlement. The problem associated with its management ranges from waste generation, collection, transportation, treatment and disposal. The study involves a kind of multi-criteria evaluation method by using geographical information technology as a practical instrument to determine the most suitable sites of landfill location in Owo Local Government Area of Ondo state. Landsat Enhanced Thematic Mapper plus (ETM+) 2002 and updated 2012 were used to map the most suitable site for waste disposal in Owo LGA. The result indicates that sites were found within the study area. The most suitable sites in the study area are located at 200metre buffer to surface water and 100metre to major and minor roads. The selected areas have 2500metres buffer zone distance from urban areas (built up areas). The study purposes acceptable landfill sites for solid waste disposal in the study area. The results achieved in this study will help policy and decision makers to take appropriate decision in considering sanitary landfill sites. -

408. Population Dynamics in Nigeria.Docx

Invited paper presented at the 6th African Conference of Agricultural Economists, September 23-26, 2019, Abuja, Nigeria Copyright 2019 by [authors]. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. Effect of population dynamics on household sustainable food security among the rural households of Jigawa state, Northwestern Nigeria *Ahungwa1, G. T., 2Sani, R.M., 1Gama, E. N & 1Adeleke, E.A. 1Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, Federal University Dutse, PMB 7156, Dutse, Jigawa State, Nigeria. www.fud.edu.ng 2Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, PMB 0248, Buachi, Nigeria. www.atbu.edu.ng *Corresponding Author Email: [email protected], Phone No: +234 (0) 703 6819 123 Abstract The study examines the effect of population dynamics on sustainable household food security among rural households in Jigawa State, Nigeria. Data collection were based on direct household survey of dietary intake from 266 households using structured questionnaire and supplementary secondary data on aggregate food production and population dynamic parameters were collected from 2001 to 2017 and analysed using food security index and double logarithmic regression model. Empirical results show the dominance of male headed households (93%) with average age of 45 years and household size of 12 members. Result of the construct of household food security index shows that 58% of the households were food insecure; subsisting on 1,667kcal/day/person as against the food security threshold of 2,730. The estimates from regression analysis show that population growth and birthrates increase significantly and consistently the likelihood of food insecurity while death rate and life expectancy exert positive and significant influence on food security.