Take Me Back: Ghostface's Ghosts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

The Uk's Top 200 Most Requested Songs in 1980'S

The Uk’s top 200 most requested songs in 1980’s 1. Billie Jean - Michael Jackson 2. Into the Groove - Madonna 3. Super Freak Part I - Rick James 4. Beat It - Michael Jackson 5. Funkytown - Lipps Inc. 6. Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This) - Eurythmics 7. Don't You Want Me? - Human League 8. Tainted Love - Soft Cell 9. Like a Virgin - Madonna 10. Blue Monday - New Order 11. When Doves Cry - Prince 12. What I Like About You - The Romantics 13. Push It - Salt N Pepa 14. Celebration - Kool and The Gang 15. Flashdance...What a Feeling - Irene Cara 16. It's Raining Men - The Weather Girls 17. Holiday - Madonna 18. Thriller - Michael Jackson 19. Bad - Michael Jackson 20. 1999 - Prince 21. The Way You Make Me Feel - Michael Jackson 22. I'm So Excited - The Pointer Sisters 23. Electric Slide - Marcia Griffiths 24. Mony Mony - Billy Idol 25. I'm Coming Out - Diana Ross 26. Girls Just Wanna Have Fun - Cyndi Lauper 27. Take Your Time (Do It Right) - The S.O.S. Band 28. Let the Music Play - Shannon 29. Pump Up the Jam - Technotronic feat. Felly 30. Planet Rock - Afrika Bambaataa and The Soul Sonic Force 31. Jump (For My Love) - The Pointer Sisters 32. Fame (I Want To Live Forever) - Irene Cara 33. Let's Groove - Earth, Wind, and Fire 34. It Takes Two (To Make a Thing Go Right) - Rob Base and DJ EZ Rock 35. Pump Up the Volume - M/A/R/R/S 36. I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) - Whitney Houston 37. -

Art to Commerce: the Trajectory of Popular Music Criticism

Art to Commerce: The Trajectory of Popular Music Criticism Thomas Conner and Steve Jones University of Illinois at Chicago [email protected] / [email protected] Abstract This article reports the results of a content and textual analysis of popular music criticism from the 1960s to the 2000s to discern the extent to which criticism has shifted focus from matters of music to matters of business. In part, we believe such a shift to be due likely to increased awareness among journalists and fans of the industrial nature of popular music production, distribution and consumption, and to the disruption of the music industry that began in the late 1990s with the widespread use of the Internet for file sharing. Searching and sorting the Rock’s Backpages database of over 22,000 pieces of music journalism for keywords associated with the business, economics and commercial aspects of popular music, we found several periods during which popular music criticism’s focus on business-related concerns seemed to have increased. The article discusses possible reasons for the increases as well as methods for analyzing a large corpus of popular music criticism texts. Keywords: music journalism, popular music criticism, rock criticism, Rock’s Backpages Though scant scholarship directly addresses this subject, music journalists and bloggers have identified a trend in recent years toward commerce-specific framing when writing about artists, recording and performance. Most music journalists, according to Willoughby (2011), “are writing quasi shareholder reports that chart the movements of artists’ commercial careers” instead of artistic criticism. While there may be many reasons for such a trend, such as the Internet’s rise to prominence not only as a medium for distribution of music but also as a medium for distribution of information about music, might it be possible to discern such a trend? Our goal with the research reported here was an attempt to empirically determine whether such a trend exists and, if so, the extent to which it does. -

Bonnie Pointer Obituary: Legendary Pointer Sisters Singer, Dies at 69 - Legacy.Com

6/11/2020 Bonnie Pointer Obituary: legendary Pointer Sisters singer, dies at 69 - Legacy.com NEWS OBITUARIES Bonnie Pointer (1950–2020), Pointer Sisters singer By Kirk Fox June 8, 2020 Bonnie Pointer started the legendary R&B group The Pointer Sisters with her sisters June and Anita in 1969. She left the group in 1977 for a solo career. Bonnie Pointer - Heaven must have sent you (video/audio edited & remastered) HQ https://www.legacy.com/news/celebrity-deaths/bonnie-pointer-1950-2020-pointer-sisters-singer/ 1/5 6/11/2020 Bonnie Pointer Obituary: legendary Pointer Sisters singer, dies at 69 - Legacy.com Died: Monday, June 8, 2020. (Who else died on June 8?) Details of Death: Died at the age of 69. We invite you to share condolences for Bonnie Pointer in our Guest Book. Singing Star Bonnie, June (1953 – 2006), and Anita started The Pointer Sisters in 1969. Older sister Ruth jo in 1972 and the R&B group had a hit in 1973 with “Yes We Can.” They blended elements of ro funk, and country into their R&B sound featuring the sisters’ terri¦c harmony singing. Bonni wrote their country crossover hit song “Fairytale” in 1974, the song reached the top 20 and wo the Grammy Award for Best song by a duo or group in country music. Bonnie left for a solo ca in 1977, she had a hit disco song in 1979 with her cover of “Heaven Must Have Sent You.” She continued to perform and reunited occasionally with her sisters. What they said about her “It is with great sadness that I have to announce to the fans of the Pointer Sisters that my sist Bonnie died this morning.” “Our family is devastated. -

Warbirds’ No-Dating Policy Exception by JIM HERRIN HERALD-CITIZEN

BIG DISTRICT WIN! CHS tops Stone. B1 Herald-CitizenWEDNESDAY,Herald-Citizen JANUARY 23, 2019 | COOKEVILLE, TENNESSEE 117TH YEAR | NO. 16 50 CENTS Commissioners reject pay raise BY JIM HERRIN “It’s been about 14 years ly enough so that it always The change would have gone “If we feel like we have HERALD-CITIZEN since the last time the coun- attracts good people.” into eff ect as of Sept. 1, 2022 earned a pay increase, we ty commission’s pay was ad- Williams made a motion when a new commission should be required to ex- The Putnam County Com- justed,” said Commissioner to set the pay for commis- takes offi ce. plain it to the public and mission Tuesday rejected Jonathan Williams. “I think sioners at fi ve percent of “We need to build in some tell them why we deserve a proposal that would have it’s safe to say that most the salary for the county kind of mechanism so that it a raise,” she said. “Rather tied their salary to that of of us don’t do this for the mayor, thereby implement- will self-adjust for infl ation than it be something that the county mayor and also money. It’s a public service. ing a system that would over time,” Williams said. automatically happens turned aside a suggestion But, by the same token, I automatically increase their Commissioner Cindy Ad- without us having to say that they give themselves a think it’s important that this pay any time the pay for the ams said that wasn’t a good fl at $50 a month increase. -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

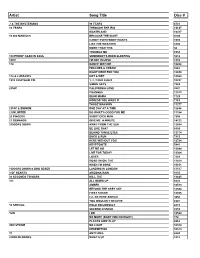

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

Selective Tradition and Structure of Feeling in the 2008 Presidential Election: a Genealogy of “Yes We Can Can”

Selective Tradition and Structure of Feeling in the 2008 Presidential Election: A Genealogy of “Yes We Can Can” BRUCE CURTIS Abstract I examine Raymond Williams’s concepts “structure of feeling” and “selective tradition” in an engagement with the novel technical-musical-cultural politics of the 2008 Barack Obama presidential election campaign. Williams hoped structure of feeling could be used to reveal the existence of pre-emergent, counter-hegemonic cultural forces, forces marginalized through selective tradition. In a genealogy of the Allen Toussaint composition, “Yes We Can Can,” which echoed a key campaign slogan and chant, I detail Toussaint’s ambiguous role in the gentrification of music and dance that descended from New Orleans’s commerce in pleasure. I show that pleasure commerce and struggles against racial segregation were intimately connected. I argue that Toussaint defanged rough subaltern music, but he also promoted a shift in the denotative and connotative uses of language and in the assignments of bodily energy, which Williams held to be evidence of a change in structure of feeling. It is the question of the counter-hegemonic potential of subaltern musical practice that joins Raymond Williams’s theoretical concerns and the implication of Allen Toussaint’s musical work in cultural politics. My address to the question is suggestive and interrogative rather than declarative and definitive. Barack Obama’s 2008 American presidential election and the post-election celebrations were the first to be conducted under the conditions of “web 2.0,” whose rapid spread from the mid-2000s is a historic “cultural break” similar in magnitude and consequence to the earlier generalization of print culture.1 In Stuart Hall’s terms, such breaks are moments in which the cultural conditions of political hegemony change.2 They are underpinned by changes in technological forces, in relations of production and communication. -

Musician Professionals to Make Your Event a Success! with Versatility and Showmanship, Rendezvous’ Journeyman Musicians Will Add a Touch of Class to Your Event

www.rendezvouspdx.com Bookings 503-901-5135 Musician Professionals to Make Your Event a Success! With versatility and showmanship, Rendezvous’ journeyman musicians will add a touch of class to your event. Their musical range and abundant talent provide so many options to entertain your guests! Rendezvous was the featured band on New Year’s Eve at Spirit Mountain Casino in 2011 and on the 2012 Portland Spirit New Year’s Eve Cruise. Here is a sample of the music we love to play: • Swing Standards like In The Mood, Misty, Smoke Gets In Your Eyes, Jump Jive and Wail. • Classic Rock Hits of the 70s through the 90s from the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Beach Boys, and Jerry Lee Lewis to Van Morrison, Journey, Blondie, and Bonnie Raitt. • R & B, Soul and Disco favorites including The Supremes, Donna Summer, Temptations, the Pointer Sisters, and KC and the Sunshine Band. • Country Music favorites from Patsy Cline and Willie Nelson, right up to current country rock hits. See the songlist on the back of this page. Meet the Musicians What Clients Say About Us Linda Lee Michelet - vocals “We knew we wanted the music to be jazzy and classy, but we couldn’t Let Linda add her elegance and class to your even come up with a specific first dance song. They helped us select songs and plan the schedule of the reception. Everybody said it was the best event. A talented and versatile singer, she’s wedding they’d been to—even my grandmother danced!” been noticed by magazines including Port- —Michelle Moravan Sebot land Monthly and More, and has been fea- tured on nationally-syndicated Better TV and “Thanks Rendezvous for a phenomenal time!” locally on OPB TV’s Oregon ArtBeat. -

Celebrate. Remember. Fight Back. Resource Guidebook Celebrate

AMERICAN CANCER SOCIETY RELAY FOR LIFE Celebrate. Remember. Fight Back. Celebrate. Remember. Fight Back. Resource Guidebook Celebrate. Remember. Fight Back. Table of Contents Section I ..........................................................................................................Page 3 What is Celebrate. Remember. Fight Back.? . Overview . Purpose . Roles and Responsibilities . Resources Section II .........................................................................................................Page 9 Celebrate . Opening Ceremony . Survivor/Caregiver Reception . Closing Ceremony . Sample Schedule of Events Section III ......................................................................................................Page 33 Remember . Luminaria Ceremony . Luminaria Lighting and Layout . Complementing Your Luminaria Ceremony Section IV .....................................................................................................Page 57 Fight Back . Fight Back Ceremony . Making the Pledge . Fight Back Activities Section V .......................................................................................................Page 71 Celebrate. Remember. Fight Back. Year-Round . RelayForLife.org . Team Captain and Committee Meetings . Kickoff and Open House Events . Event Communications and Local Media www.RelayForLife.org 1 007831 Deborah Mohlenhoff Deborah Mohlenhoff has been a Relay For Life The first time Mohlenhoff witnessed a team captain, event chair, and an American Luminaria Ceremony, she walked around the -

· 00 Kwajalein Hourglass

·00 KWAJALEIN HOURGLASS VOLUME XXIII, NO 207 U S ARMY KWAJALEIN MISSILE RANGE, MARSHALL ISLANDS MONDAY, OCTOBER 27, 1986 Has nfus. Leaders Fast And Pray For Peace Contras Were To Handle Supply Flights By SAMUEL KOO Assoclated Press Wrlter rlcan beads -- agaInst the By ROBERT PARRY church's facade of pInk and Assoclated Press Wrlter carryIng weapons for the U S - ASSISI, Italy -- UnIted In a beIge stones backed rebels was shot down quest for peace, Pope John Paul As thousands of onlookers MANAGUA, Nlcaragua -- Contra over southern NIcaragua on II and leaders of 11 major non applauded, the pontIff arrlved rebels were supposed to handle Oct 5 He IS beIng trIed be ChrIstIan rellglons, from AfrI In a motorcade from nearby thelr own supply fllghts, but fore a speCIal court, and could can anImIsts to Japanese ShIn Perugla and shook hands WIth Amerlcans took over because be sentenced for up to 30 years tOISts, fasted and prayed to the heads of more than 60 dele the Contras dldn't do the Job for hIS role In SupplYIng the gether today gatIons representIng the spec properly, Amerlcan Eugene Has rebels In a gesture of solIdarIty trum of faIths enfus says "In other words, here, we and support, several of the The fIrst to greet the pope "The operatlon was supposed take these aIrcraft down to world's warrIng governments and was the Dalal Lama, the eXIled to be sold to the Contras," Aguacate (a US-bUIlt aIrfIeld Insurgent groups promIsed to BuddhIst god-kIng of TIbet sald Hasenfus, who was captured In Honduras) Here are these observe the pope's -

The BG News March 11, 2020

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 3-11-2020 The BG News March 11, 2020 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation State University, Bowling Green, "The BG News March 11, 2020" (2020). BG News (Student Newspaper). 9134. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/9134 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. DEMAND FOR DETAILS bg Opinion: Administration took too long to notify students about COVID-19 response | Page 4 news An independent student press serving the campus and surrounding community, ESTABLISHED 1920 Bowling Green State University Wednesday,March 11, 2020 Volume 99, Issue 29 Microaggressions impact BGSU students Page 2 Songs to get you through the week Page 8 COVID-19 affects MAC attendance Page 11 LOCATED ON BGSU’S CAMPUS FULLY FURNISHED ACADEMIC YEAR AND SUMMER HOUSING AGREEMENTS INDIVIDUAL GRADUATE, FACULTY, AND STAFF HOUSING HOUSING AGREEMENTS www.falconlandingbg.com • 419-806-4478 ALL-INCLUSIVE RATES BEGIN facebook.com/falconlanding/ falconlandingbgsu falconlandingbg AT $640 PER PERSON BG NEWS March 11, 2020 | PAGE 2 Microaggression research shows power of words, need for education Brionna Scebbi explored the way microaggressive words and and “old-fashioned racism,” she said. Editor-in-Chief actions are impacting their peers. Microinsults and microinvalidations Fitzpatrick, a sophomore social work major are more common as they are typically “You’re so articulate.” and ethnic studies minor, was part of the unintentional and based on a person’s panel along with senior graphic design major implicit, or subconscious, biases. -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research.