MUSE Issue 14, June 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendices 2011–12

Art GAllery of New South wAleS appendices 2011–12 Sponsorship 73 Philanthropy and bequests received 73 Art prizes, grants and scholarships 75 Gallery publications for sale 75 Visitor numbers 76 Exhibitions listing 77 Aged and disability access programs and services 78 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander programs and services 79 Multicultural policies and services plan 80 Electronic service delivery 81 Overseas travel 82 Collection – purchases 83 Collection – gifts 85 Collection – loans 88 Staff, volunteers and interns 94 Staff publications, presentations and related activities 96 Customer service delivery 101 Compliance reporting 101 Image details and credits 102 masterpieces from the Musée Grants received SPONSORSHIP National Picasso, Paris During 2011–12 the following funding was received: UBS Contemporary galleries program partner entity Project $ amount VisAsia Council of the Art Sponsors Gallery of New South Wales Nelson Meers foundation Barry Pearce curator emeritus project 75,000 as at 30 June 2012 Asian exhibition program partner CAf America Conservation work The flood in 44,292 the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit ANZ Principal sponsor: Archibald, Japan foundation Contemporary Asia 2,273 wynne and Sulman Prizes 2012 President’s Council TOTAL 121,565 Avant Card Support sponsor: general Members of the President’s Council as at 30 June 2012 Bank of America Merill Lynch Conservation support for The flood Steven lowy AM, Westfield PHILANTHROPY AC; Kenneth r reed; Charles in the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit Holdings, President & Denyse -

2013 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census and Survey

2013 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census and Survey 43-51 Cowper Wharf Road September 2013 Woolloomooloo NSW 2011 w: www.mgnsw.org.au t: 61 2 9358 1760 Introduction • This report is presented in two parts: The 2013 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census and the 2013 NSW Small to Medium Museum & Gallery Survey. • The data for both studies was collected in the period February to May 2013. • This report presents the first comprehensive survey of the small to medium museum & gallery sector undertaken by Museums & Galleries NSW since 2008 • It is also the first comprehensive census of the museum & gallery sector undertaken since 1999. Images used by permission. Cover images L to R Glasshouse, Port Macquarie; Eden Killer Whale Museum , Eden; Australian Fossil and Mineral Museum, Bathurst; Lighting Ridge Museum Lightning Ridge; Hawkesbury Gallery, Windsor; Newcastle Museum , Newcastle; Bathurst Regional Gallery, Bathurst; Campbelltown arts Centre, Campbelltown, Armidale Aboriginal Keeping place and Cultural Centre, Armidale; Australian Centre for Photography, Paddington; Australian Country Music Hall of Fame, Tamworth; Powerhouse Museum, Tamworth 2 Table of contents Background 5 Objectives 6 Methodology 7 Definitions 9 2013 Museums and Gallery Sector Census Background 13 Results 15 Catergorisation by Practice 17 2013 Small to Medium Museums & Gallery Sector Survey Executive Summary 21 Results 27 Conclusions 75 Appendices 81 3 Acknowledgements Museums & Galleries NSW (M&G NSW) would like to acknowledge and thank: • The organisations and individuals -

Faculty of Law Handbook 1995 Faculty of Law Handbook 1995 ©The University of Sydney 1994 ISSN 1034-2656

The University of Sydney Faculty of Law Handbook 1995 Faculty of Law Handbook 1995 ©The University of Sydney 1994 ISSN 1034-2656 The address of the Law School is: The University of Sydney Law School 173-5 Phillip Street Sydney, N.S.W. 2000 Telephone (02) 232 5944 Document Exchange No: DX 983 Facsimile: (02) 221 5635 The address of the University is: The University of Sydney N.S.W. 2006 Telephone 351 2222 Setin 10 on 11.5 Palatino by the Publications Unit, The University of Sydney and printed in Australia by Printing Headquarters, Sydney. Text printed on 80gsm recycled bond, using recycled milk cartons. Welcome from the Dean iv Location of the Law School vi How to use the handbook vii 1. Staff 1 2. History of the Faculty of Law 3 3. Law courses 4 4. Undergraduate degree requirements 7 Resolutions of the Senate and the Faculty 7 5. Courses of study 12 6. Guide for law students and other Faculty information 24 The Law School Building 24 Guide for law students 24 Other Faculty information 29 Law Library 29 Sydney Law School Foundation 30 Sydney Law Review 30 Australian Centre for Environmental Law 30 Institute of Criminology 31 Centre for Plain Legal Language 31 Centre for Asian and Pacific Law 31 Faculty societies and student representation 32 Semester and vacation dates 33 The Allen Allen and Hemsley Visiting Fellowship 33 Undergraduate scholarships and prizes 34 7. Employment 36 Main Campus map 39 The legal profession in each jurisdiction was almost entirely self-regulating (and there was no doubt it was a profession, and not a mere 'occupation' or 'service industry'). -

Georgia Kriz “We Aren’T Worth Enough to Them” Reviews Revues

Week 4, Semester 2, 2014 HONI I SHRUNK THE KIDS ILLUSTRATION BY AIMY NGUYEN p.12 Arrested at Leard p.15 In defense of the WWE Georgia Kriz “We aren’t worth enough to them” reviews revues. This past weekend it rained a lot. place, prevalence and prominence of However, since non-faculty lower tiers of funding, and thus can This was unfortunate for the cast cultural, minority and non-faculty revues traditionally receive less only book the smallest Seymour of Queer Revue, because the Union revues. funding than their faculty-backed space. And in order to graduate assigns us the Manning Forecourt counterparts, their road has not to the higher tiers of funding, to rehearse in on the weekends, and The problems facing non-faculty been easy. The Union allocates revues have to sell out this theatre so, when confronted with a veritable revues begin at their inception. between $4000 and $8000 to each completely. But with a limited downpour on Sunday morning, Entering the crowded revue revue. According to a spokesperson budget to spend on production, props we were forced to shop around for marketplace is an uphill battle from the Programs Office, the exact and advertising, smaller revues are another space. for new revues. After a period of amount allocated depends solely significantly hamstrung. And for dormancy, in 2011 several women upon which Seymour Centre theatre Queer Revue and Jew Revue, there But with all other rehearsal attempted to revive the Wom*n’s space a revue can sell out. Both Jew is no faculty to fall back on to fill the spaces occupied by faculty revues Revue. -

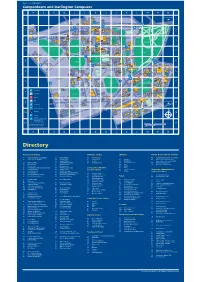

Camperdown and Darlington Campuses

Map Code: 0102_MAIN Camperdown and Darlington Campuses A BCDEFGHJKLMNO To Central Station Margaret 1 ARUNDEL STREETTelfer Laurel Tree 1 Building House ROSS STREETNo.1-3 KERRIDGE PLACE Ross Mackie ARUNDEL STREET WAY Street Selle Building BROAD House ROAD Footbridge UNIVERSITY PARRAMATTA AVENUE GATE LARKIN Theatre Edgeworth Botany LANE Baxter's 2 David Lawn Lodge 2 Medical Building Macleay Building Foundation J.R.A. McMillan STREET ROSS STREET Heydon-Laurence Holme Building Fisher Tennis Building Building GOSPER GATE AVENUE SPARKES Building Cottage Courts STREET R.D. Watt ROAD Great Hall Ross St. Building Building SCIENCE W Gate- LN AGRICULTURE EL Bank E O Information keepers S RUSSELL PLACE R McMaster Building P T Centre UNIVERSITY H Lodge Building J.D. E A R Wallace S Badham N I N Stewart AV Pharmacy E X S N Theatre Building E U ITI TUNN E Building V A Building S Round I E C R The H Evelyn D N 3 OO House ROAD 3 D L L O Quadrangle C A PLAC Williams Veterinary John Woolley S RE T King George VI GRAFF N EK N ERSITY Building Science E Building I LA ROA K TECHNOLOGY LANE N M Swimming Pool Conference I L E I Fisher G Brennan MacCallum F Griffith Taylor UNIV E Centre W Library R Building Building McMaster Annexe MacLaurin BARF University Oval MANNING ROAD Hall CITY R.M.C. Gunn No.2 Building Education St. John's Oval Old Building G ROAD Fisher Teachers' MANNIN Stack 4 College Manning 4 House Manning Education Squash Anderson Stuart Victoria Park H.K. -

Education Resource

Education Resource This education resource has been developed by the Art Gallery of New South Wales and is also available online An Art Gallery of New South Wales exhibition toured by Museums & Galleries NSW DRAWING ACTIVITIES Draw with black pencil on white paper then with white pencil on black paper. How does the effect differ? Shade a piece of white paper using a thick piece of charcoal then use an eraser to draw into the tone to reveal white lines and shapes. Experiment with unconventional materials such as shoe polish and mud on flattened cardboard boxes. Use water on a paved surface to create ephemeral drawings. Document your drawings before they disappear. How do the documented forms differ from the originals? How did drawing with an eraser, shoe polish, mud and water compare to drawing with a pencil? What do you need to consider differently as an artist? How did handling these materials make you feel? Did you prefer one material to another? Create a line drawing with a pencil, a tonal drawing with charcoal and a loose ink drawing with a brush – all depicting the same subject. Compare your finished drawings. What were some of the positive and negatives of each approach? Is there one you prefer, and why? Draw without taking your drawing utensil off the page. What was challenging about this exercise? Draw something from observation without looking down at your drawing. Are you pleased with the result? What did you learn? Create a series of abstract pencil drawings using colours that reflect the way you feel. -

5-7 December, Sydney, Australia

IRUG 13 5-7 December, Sydney, Australia 25 Years Supporting Cultural Heritage Science This conference is proudly funded by the NSW Government in association with ThermoFisher Scientific; Renishaw PLC; Sydney Analytical Vibrational Spectroscopy Core Research Facility, The University of Sydney; Agilent Technologies Australia Pty Ltd; Bruker Pty Ltd, Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences; and the John Morris Group. Conference Committee • Paula Dredge, Conference Convenor, Art Gallery of NSW • Suzanne Lomax, National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA • Boris Pretzel, (IRUG Chair for Europe & Africa), Victoria and Albert Museum, London • Beth Price, (IRUG Chair for North & South America), Philadelphia Museum of Art Scientific Review Committee • Marcello Picollo, (IRUG chair for Asia, Australia & Oceania) Institute of Applied Physics “Nello Carrara” Sesto Fiorentino, Italy • Danilo Bersani, University of Parma, Parma, Italy • Elizabeth Carter, Sydney Analytical, The University of Sydney, Australia • Silvia Centeno, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA • Wim Fremout, Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, Brussels, Belgium • Suzanne de Grout, Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, Amsterdam, The Netherlands • Kate Helwig, Canadian Conservation Institute, Ottawa, Canada • Suzanne Lomax, National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA • Richard Newman, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA • Gillian Osmond, Queensland Art Gallery|Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, Australia • Catherine Patterson, Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles, USA -

The James Gleeson Oral History Collection

research library Painted in words: the James Gleeson oral history collection It doesn't matter how the paint is put on, as long as something is said. Jackson Pollock Rosemary Madigan Eingana 1968 The Research Library at the National Gallery of Australia Oral history has an interesting place in a museum carved English lime wood collects catalogues raisonn•, auction catalogues, rare serials context. It revolves around the power and reliability of 61.0 x364.8 x30.4cm and books and other printed and pictorial media relating memory and the spoken word in an environment that National Gallery of Australia, Canberra to the visual arts. In addition to bibliographic collections, more often values the written word, the document, the Purchased 1980 the library keeps manuscripts and documentary material image and the object. Spoken words have a number of Murray Griffin such as diaries, photographs and ephemera. It also holds qualities that make them different from other ways of Rabbit trapper's daughter 1936 communicating. They are able to capture the emotions linocut, printed in colour, from a collection of ninety-eight recorded interviews and multiple blocks behind what it means to be a person who is living printed image 35.0 x 27.8 cm transcripts with Australian artists created in the late 1970s, and making art at a particular time in history. And the National Gallery of Australia, before the National Gallery of Australia was built. Canberra storytelling in the interview captures both the pleasures of The interviews were conducted by the well-known memory and the act of creativity. -

Inge King Eulogy

Inge King Memorial Service NGV Great Hall, Monday 9 May 2016, 10:30 am I’m deeply honoured to be speaking today about Inge’s extraordinary career. I’m conscious of there being many others eminently qualified to speak, including Professors Judith Trimble and Sasha Grishin, each of whom have published eloquent monographs on Inge, and Professors Margaret Plant and Jenny Zimmer, who have both written informed, extended essays for two of Inge’s earliest survey exhibitions. In addition the NGV’s curator of Australian art, David Hurlston, and former NGV curator and recently retired director of the Geelong Gallery, Geoffrey Edwards, have both worked closely with Inge in the sensitive presentation of two retrospectives held here at the gallery, in 1992 and 2014. In the presence of such a wealth of knowledge and experience, I’m frankly humbled to have been asked to speak. I’d like to briefly mention how I came to know Inge, if only to contextualise my appearance here. Inge was arguably the best-known member of the Centre Five group, which forms the subject of my PhD thesis. I began reading about her work in 2008, while still living in Ireland and planning a return to Australia after a nine-year absence. The reading prompted faint memories of seeing her work at the Queensland Art Gallery while still a student in Brisbane. The following year, six months after embarking on doctoral studies at Melbourne University, I finally met my appointed supervisor, Professor Charles Green, who had until then been on sabbatical. One of the first things he said to me at that meeting was: ‘Now, you do know I’m Inge King’s godson, don’t you?’ Well, no, I didn’t. -

Teacher Lesson Plan Surrealism – an Introductory Study of Australian Artists

Teacher Lesson Plan Surrealism – An introductory study of Australian artists Lesson Title: Surrealism – An introductory study of Australian artists Stage: Year 10 - Stage 5 Year Group: 15-16 years old Resources/Props: Work books and writing materials, or digital device equivalents National Gallery of Australia website information page: Twentieth Century Australian Art - James Gleeson The Citadel 1945 National Gallery of Australia website link: Australian art: Surrealism National Gallery of Australia website link: Dada and Surrealism Downloadable worksheets: Surrealism-Australian artist study Acrylic paints and their choice of cardboard, canvas or composition board Language/vocabulary: Reality, unrealistic, depiction, landscape, minimal, movement, Surrealism, citadel, subversion purpose, influential, prominent, Surrealist, international, dada, collage, photographs, sculpture, influenced, critical, analysis, stimulus, characteristics, expressionistic, juxtaposition, distorted, exaggerated, symbolism, imagery, fantasy, inspiration, elements, primary, secondary, society, culture, exquisite corpse, horror, hallucination, satire, anarchy, subconscious, incongruous, mimetic, biomorphism Lesson Overview: In this lesson, students will be introduced to the international Surrealist art movement of the 1920’s and its influence on a number of Australian artists who adopted it to convey their strong feelings about war, politics and philosophy in the early 20th century. Students will be able to identify the differences between conventional and Surrealist -

Genetic Counsellor

Genetic Counsellor Reports to Professor Glenda Halliday Brain and Mind Centre Organisational area Faculty of Medicine Central Clinical School Position summary The Genetic Counsellor will provide research participants and/or their family members with information and support regarding any genetic risks associated with the neurodegenerative conditions being researched, the implications for the participant and their families in participating in the genetic research, and whether participants have any concerns or issues that warrant other health professional referrals. More information about the specific role requirements can be found in the position description at the end of this document. Location Charles Perkins Centre Camperdown/Darlington Campus Type of appointment Full-time fixed term opportunity for 3 years. Flexible working arrangements will also be considered. Salary Remuneration package: $97,156 p.a. (which includes a base salary Level 6 $82,098 p.a., leave loading and up to 17% employer’s contribution to superannuation). How to apply All applications must be submitted online via the University of Sydney careers website. Visit sydney.edu.au/recruitment and search by reference number 2231/1017 for more information and to apply. 1 For further information For information on position responsibilities and requirements, please see the position description attached at the end of this document. Intending applicants are welcome to seek further information about the position from: Jude Amal Raj Research Officer 02 9351 0753 [email protected] For enquiries regarding the recruitment process, please contact: Sarah Daji Talent Acquisition Consultant 02 8627 6362 [email protected] The University of Sydney About us The University of Sydney is a leading, comprehensive research and teaching university. -

The University Archives – Record 2015

THE UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES 2015 Cover image: Students at Orientation Week with a Dalek, 1983. [G77/1/2360] Forest Stewardship Council (FSC®) is a globally recognised certification overseeing all fibre sourcing standards. This provides guarantees for the consumer that products are made of woodchips from well-managed forests, other controlled sources and reclaimed material with strict environmental, economical social standards. Record The University Archives 2015 edition University of Sydney Telephone Directory, n.d. [P123/1085] Contact us [email protected] 2684 2 9351 +61 Contents Archivist’s notes............................... 2 The pigeonhole waltz: Deflating innovation in wartime Australia ............................ 3 Aboriginal Photographs Research Project: The Generous Mobs .......................12 Conservatorium of Music centenary .......................................16 The Seymour Centre – 40 years in pictures ........................18 Sydney University Regiment ........... 20 Beyond 1914 update ........................21 Book review ................................... 24 Archives news ................................ 26 Selected Accession list.................... 31 General information ....................... 33 Archivist‘s notes With the centenary of WWI in 1914 and of ANZAC this year, not seen before. Our consultation with the communities war has again been a theme in the Archives activities will also enable wider research access to the images during 2015. Elizabeth Gillroy has written an account of where appropriate. a year’s achievements in the Beyond 1914 project. The impact of WWI on the University is explored through an 2015 marks another important centenary, that of the exhibition showing the way University men and women Sydney Conservatorium of Music. To mark this, the experienced, understood and responded to the war, Archives has made a digital copy of the exam results curated by Nyree Morrison, Archivist and Sara Hilder, from the Diploma of the State Conservatorium of Music, Rare Books Librarian.