Wisconsin Death Trip: an Excursion Into the Midwestern Gothic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Alcalá COMISIÓN DE ESTUDIOS OFICIALES DE POSGRADO Y DOCTORADO

� Universidad /::.. f .. :::::. de Alcalá COMISIÓN DE ESTUDIOS OFICIALES DE POSGRADO Y DOCTORADO ACTA DE EVALUACIÓN DE LA TESIS DOCTORAL Año académico 201Ci/W DOCTORANDO: SERRANO MOYA, MARIA ELENA D.N.1./PASAPORTE: ****0558D PROGRAMA DE DOCTORADO: D402 ESTUDIOS NORTEAMERICANOS DPTO. COORDINADOR DEL PROGRAMA: INSTITUTO FRANKLIN TITULACIÓN DE DOCTOR EN: DOCTOR/A POR LA UNIVERSIDAD DE ALCALÁ En el día de hoy 12/09/19, reunido el tribunal de evaluación nombrado por la Comisión de Estudios Oficiales de Posgrado y Doctorado de la Universidad y constituido por los miembros que suscriben la presente Acta, el aspirante defendió su Tesis Doctoral, elaborada bajo la dirección de JULIO CAÑERO SERRANO// DAVID RÍO RAIGADAS. Sobre el siguiente tema: VIEWS OF NATIVEAMERICANS IN CONTEMPORARY U.S. AMERICAN CINEMA Finalizada la defensa y discusión de la tesis, el tribunal acordó otorgar la CALIFICACIÓN GLOBAL 1 de (no apto, ) aprobado, notable y sobresaliente : _=-s·--'o---'g""'--/\.-E._5_---'-/l i..,-/ _&_v_J_�..::;_________ ______ Alca la, de Henares, .............,t-z. de ........J&Pr.........../015"{(,.......... de ..........2'Dl7.. .J ,,:: EL SECRETARIO u EL PRESIDENTE .J ,,:: UJ Q Q ,,:: Q V) " Fdo.: AITOR UJ Fdo.: FRANCISCO MANUEL SÁEZ DE ADANA HERRERO Fdo.:MARGARITA ESTÉVEZ SAÁ > IBARROLLA ARMENDARIZ z ;::, Con fe0hag.E_de__ ��{� e__ � j:l1a Comisión Delegada de la Comisión de Estudios Oficiales de Posgrado, a la vista de los votos emitidos de manera anónima por el tribunal que ha juzgado la tesis, resuelve: FIRMA DEL ALUMNO, O Conceder la Mención de "Cum Laude" � No conceder la Mención de "Cum Laude" La Secretariade la Comisión Delegada Fdo.: SERRANO MOYA, MARIA ELENA 1 La calificación podrá ser "no apto" "aprobado" "notable" y "sobresaliente". -

The University of Bradford Institutional Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bradford Scholars The University of Bradford Institutional Repository http://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk This work is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our Policy Document available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this work please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published online version may require a subscription. Citation: Goodall M (2016) Spaghetti savages: cinematic perversions of 'Django Kill'. In: Broughton L (Ed.) Critical perspectives on the Western: from A Fistful of Dollars to Django Unchained. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. 199-212. Copyright statement: © 2016. Rowman & Littlefield. All rights reserved. Reproduced in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. ‘Spaghetti Savages’: the cinematic perversions of Django Kill Mark Goodall Introduction: the ‘Savage Western’ …The world of the Italian western is that of an insecure environment of grotesqueness, abounding in almost surrealistic dimensions, in which violence reigns1 The truth in stories always generates fear2 It is widely accepted that the ‘Spaghetti Western’, one of the most vivid genres in cinematic history, began with Sergio Leone’s 1964 film Per un pugno di dollari/A Fistful of Dollars. Although A Fistful of Dollars was not the first Italian Western per se, it was the first to present a set of individual and distinctive traits for which Latino versions of the myths of the West would subsequently become known. In short, Leone’s much imitated film served to introduce a sense of ‘separate generic identity’3 to the Italian Western The blank, amoral character of ‘The Man With No Name’, played by the American television actor Clint Eastwood, was something of a surprise initially but his cool manner under extreme provocation from all sides was an engaging and powerful attribute. -

The 15Th International Gothic Association Conference A

The 15th International Gothic Association Conference Lewis University, Romeoville, Illinois July 30 - August 2, 2019 Speakers, Abstracts, and Biographies A NICOLE ACETO “Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut”: The Terror of Domestic Femininity in Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House Abstract From the beginning of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, ordinary domestic spaces are inextricably tied with insanity. In describing the setting for her haunted house novel, she makes the audience aware that every part of the house conforms to the ideal of the conservative American home: walls are described as upright, and “doors [are] sensibly shut” (my emphasis). This opening paragraph ensures that the audience visualizes a house much like their own, despite the description of the house as “not sane.” The equation of the story with conventional American families is extended through Jackson’s main character of Eleanor, the obedient daughter, and main antagonist Hugh Crain, the tyrannical patriarch who guards the house and the movement of the heroine within its walls, much like traditional British gothic novels. Using Freud’s theory of the uncanny to explain Eleanor’s relationship with Hill House, as well as Anne Radcliffe’s conception of terror as a stimulating emotion, I will explore the ways in which Eleanor is both drawn to and repelled by Hill House, and, by extension, confinement within traditional domestic roles. This combination of emotions makes her the perfect victim of Hugh Crain’s prisonlike home, eventually entrapping her within its walls. I argue that Jackson is commenting on the restriction of women within domestic roles, and the insanity that ensues when women accept this restriction. -

Contemporary Australian Gothic Theatre Sound Miles Henry O'neil

Contemporary Australian Gothic Theatre Sound Miles Henry O’Neil ORCID ID: 0000-0003-0192-7783 Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2018 Faculty of Victorian College of the Arts & Melbourne Conservatorium of Music University of Melbourne Abstract This practice-based research analyses the significance of sonic dramaturgies in the development and proliferation of contemporary Australian Gothic theatre. Taking an acoustemological approach, I consider the dramaturgical role of sound and argue that it is imperative to the construction and understanding of contemporary Gothic theatre and that academic criticism is emergent in its understanding. By analysing companies and practitioners of contemporary Australian Gothic theatre, I identify and articulate their innovative contributions towards what has been called “the Sonic Turn”. My case studies include Black Lung Theatre and Whaling Firm and practitioner Tamara Saulwick. I argue that the state of Victoria has a particular place in the development of contemporary Gothic theatre and highlight the importance of the influences of Gothic Rock, rock band aesthetics, Nick Cave, and the Gothic myths and legends and specific landscapes of Victoria. I identify dramaturgical languages that describe the function of sound in the work of these practitioners and the crucial emergence of sound as a dominant affective device and its use in representing imagined landscapes of post-colonial Australia. I also analyse sound in relation to concepts of horror and trauma. I position my practice and my work as co-artistic director of the Suitcase Royale within the Sonic Turn and in relation to other Gothic theatre companies and practitioners. -

Thesis Complete

“BECAUSE SOME STORIES DO LIVE FOREVER”: STEPHEN KING’S THE DARK TOWER SERIES AS MODERN ROMANCE BY RACHEL MCMURRAY Submitted to the graduate degree program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ___________________________________ Chairperson Prof. Misty Schieberle ___________________________________ Prof. Giselle Anatol ___________________________________ Prof. Kathryn Conrad Date Defended: April 6, 2012 ii The Thesis Committee for RACHEL MCMURRAY certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: “BECAUSE SOME STORIES DO LIVE FOREVER”: STEPHEN KING’S THE DARK TOWER SERIES AS MODERN ROMANCE ________________________________ Chairperson Prof. Misty Schieberle Date approved: April 6, 2012 iii Abstract Stephen King’s Dark Tower series is a seven-volume work that contains elements from myths, fairy tales, American westerns, legends, popular culture, Gothic literature, and medieval romance. Few scholars have engaged with this series, most likely due to its recent completion in 2004 and its massive length, but those who do examine the Dark Tower focus on classifying its genre, with little success. As opposed to the work of the few scholars who have critically engaged with King’s work (and the smaller number still who have written about the Dark Tower), I will examine the ways in which he blends genres and then go further than scholars like Patrick McAleer, Heidi Strengell, James Egan, and Tony Magistrale, to argue that King’s use of motifs, character types, and structure has created his own contemporary version of a medieval romance in the Arthurian tradition. My analysis of King’s work through this lens of Arthurian romance crosses continents and centuries in an attempt to bring together medieval studies and contemporary American fiction. -

Richard Brautigan Committed Suicide in a House He Owned in Bolinas, California, a Small Coastal Town Some Twenty Miles North of San Francisco

by Jay Boyer PS m W4 13 no .19 o o Boise State University Western Writers Series Number 79 By Jay Boyer Arizona State University Editors: Wayne Chatterton James H. Maguire Business Manager: James Hadden Cover Design and Illustration by Amy Skov, Copyright 1987 Boise State University, Boise, Idah o Copyright 1987 by the Boise State University Western Writers Series ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Libra ry of Congress Card No. 87·70030 International Standard Book No. Cl-8843().()78.1 Selections from Tlu AbQrlion, T1u Hawklim Mr.mster, Willard and His Bawl ing Trophies, Sombrero Falkme, and Dreaming ofBabylon are reprinted by per mission of Simon & Schuster. Printed in the United States of America by Boise State University Printing and Graphics Services Boise, Idaho At the age of forty-nine, Richard Brautigan committed suicide in a house he owned in Bolinas, California, a small coastal town some twenty miles north of San Francisco. Files from the Marin County Coroner's office and the office of the Sheriff of Marin Coun ty suggest that he stood at the foot of his bed looking out a window and put a handgun to his head, a Smith & Wesson .44 Magnum he'd borrowed from his friend Jimmy Sakata, the sixty year-old proprietor of Cho-Cho's, a Japanese restaurant in San Fran cisco that Brautigan was particularly fond of. He shot himself around the first of October 1984. The precise date of his suicide cannot be determined since he was living alone at the time and his body, so badly decomposed that it defied recognition, was not discovered until 25 October 1984. -

Glowing Like Phosphorus: Dorothea Tanning and the Sedona Western

Journal of Surrealism and the Americas 10:1 (2019), 84-105 84 Glowing Like Phosphorus: Dorothea Tanning and the Sedona Western Catriona McAra Leeds Arts University I like the work of Dorothea Tanning because the domain of the marvelous is her native country… —Max Ernst, 1944 People often speak of being profoundly affected by Sedona, the Arizonian red rock country where Dorothea Tanning and Max Ernst decamped in 1946. Following the skyscraper urbanity of the claustrophobic New York art scene, Sedona offered restorative possibilities for the surrealist imagination as a faraway sanctuary. Patrick Waldberg described their rudimentary desert retreat as “a pioneer’s cabin such as one sees in westerns.”1 Ernst was also fascinated by Native American artefacts, and in Sedona his penchant was well catered for in the collectable shape of colorful Hopi and Katsina figures and other ritual objects which decorated his living quarters with Tanning. After frequenting curio dealers during his time in New York, as well as purchasing souvenirs at a trading post near the Grand Canyon, he had built up a sizeable collection of indigenous art forms, such as Northern Pacific Kwakiutl totems.2 Indeed, Ernst first came across the red rock country of the Southwest in 1941, on a return journey to the West Coast with his son Jimmy Ernst and third wife Peggy Guggenheim. As is now well-known, he coveted Sedona due to the landscape’s prophetic likeness to his earlier paintings such as La ville entière (The Entire City) (1934-37). Roland Penrose tells us: “the surroundings were astonishingly like the most fantastic landscapes Max had painted before ever seeing the Wild West. -

Author Last Prefix

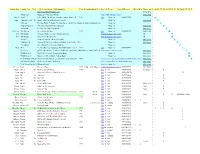

Author_First - Author_Last Prefix - Title -- Last Update 2003-August-16 Year SettingMulticultural ThemesAmazonLvl Theme Own i SBN (no i ) AR LevelAR ptsComments RecAtwellBourque (A)ChicagoCalif (B)Frstbrn24 CDCEGirls (D)MacKnight (F)NewberyOaklandPat RiefRAllison USDTCY (P)W X * * http://www.WelchEnglish.com/ i Merged List of0 Recommended and Favorite Books for Adolescent Readers * * About.com About.com - Historical Fiction http://childrensbooks.about.com/cs/historicalfiction/i http://childrensbooks.about.com/cs/historicalfiction/0 Nancie * Atwell In the Middle: New Understandings About Writing, Reading,1998 and Learning http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0867093749/timstore06-20* * Book List i 0867093749 1 A Louise * Bourque (and GwenThe Johnson)Book Ladies' List of Students' Favorites * * Book List i http://www.qesnrecit.qc.ca/ela/refs/books.htm1 B * * Chicago Chicago Public Schools - Reading List (recommended books for high school students) * * Book List i 1 C * * Dept of Ed, Calif * Reading List for California Students * * Book List i http://www.cde.ca.gov/literaturelist/litsearch.asp1 D * * Frstbrn24 Reading List 2002: Firstbrn24 * * Book List i http://pages.ivillage.com/frstbrn24/readinglist2002.htm1 F Kathleen * G - Odean Great Books for Girls 1997 http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0345450213/timstore06-20* * Book List 1 i 0345450213 Updated 20021 edition also availableG Eric * MacKnight Favourite Books as chosen by my students http://homepage.mac.com/ericmacknight/favbks.htmli UK 1 M Eric * MacKnight Independent Reading -

II Book.Indd

Subaltern Narratives: A Critical Stance Editors Dr K Ravichandran Dr C Anita EMERALD PUBLISHERS Subaltern Narratives: A Critical Stance Editors Dr. K. Ravichandran Dr C Anita © Emerald Publishers, 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microfilm, xerography, or any other means, or incorporated into any information retrieval system, electronic or mechanical, without the written permission of the copyright holder. Published by Olivannan Gopalakrishnan Emerald Publishers 15A, First Floor, Casa Major Road Egmore, Chennai – 600 008. : +91 44 28193206, 42146994 : [email protected] : www.emeraldpublishers.com Price : ` 00 ISBN : 978-8xxxxxxxxx Printed at xxxxxxx Contents 1. Realization A Critical Analysis of Amiri Baraka’s Slave - Ship 1 2. Race and Racism in Chimamanda Ngozi’s Americanah 5 3. Science and Philosophy in The Calcutta Chromosomes 9 4. Suppression and Caste Feud in Bama’s Karukku 13 5. Patriarchy and Feministic views in Jaishree Misra’s Ancient Promises 18 6. Black Feminism in Toni Morrison’s Sula 24 7. Mother –Daughter Relationship as a Key Note of Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy 28 8. Gender Discrimination 31 9. Postcolonial literature: Dynamics of Diaspora 34 10. Social Conditions of Africans in Petals of Blood 41 11. Cinder: The Fantasy of Young Adult 45 12. Narrating Childhood in Aravind Malagatti’s Government Brahmana: From a Subaltern Perspectives 47 13. Feminism in Shashi Deshpane’s Novels 58 14. Rxxxxxxxxxxx 61 15. A study of Neo Hoo –Doo Philosophy in Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo 66 16. Self- Confi nment of Masha in Chekhov’s Three Sisters 69 17. -

I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

I Thesis/Dissertation Sheet I Australia's -1 Global UNSW University I SYDN�Y I Surname/Family Name Dempsey Given Name/s Claire Kathleen Marsden Abbreviation for degree as give in the University calendar MPhil Faculty UNSW Canberra I School School of Humanities and Social Sciences Thesis Title 'A quick kiss in the dark from a stranger': Stephen King and the Short Story Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) There has been significant scholarly attention paid to both the short story genre and the Gothic mode, and to the influence of significant American writers, such as Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne and H.P. Lovecraft, on the evolution of these. However, relatively little consideration appears to have been offeredto the I contribution of popular writers to the development of the short story and of Gothic fiction. In the Westernworld in the twenty-firstcentury there is perhaps no contemporary popular writer of the short story in the Gothic mode I whose name is more familiar than that of Stephen King. This thesis will explore the contribution of Stephen King to the heritage of American short stories, with specific reference to the American Gothic tradition, the I impact of Poe, Hawthorneand Lovecrafton his fiction, and the significance of the numerous adaptations of his works forthe screen. I examine Stephen King's distinctive style, recurring themes, the adaptability of his work I across various media, and his status within American popular culture. Stephen King's contribution to the short story genre, I argue, is premised on his attention to the general reader and to the evolution of the genre itself, I providing as he does a conduit between contemporary an_d classic short fiction. -

HOLLYWOOD's WEST: the American Frontier in Film, Television, And

o HOLLYWOOD’S WEST WEST*FrontMtr.pmd 1 8/31/05, 4:52 PM This page intentionally left blank HOLLYWOOD’S WEST The American Frontier in o Film, Television, and History EDITED BY PETER C. ROLLINS JOHN E. O’CONNOR THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY WEST*FrontMtr.pmd 3 8/31/05, 4:52 PM Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2005 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508–4008 www.kentuckypress.com 0908070605 54321 “Challenging Legends, Complicating Border Lines: The Concept of ‘Frontera’ in John Sayles’s Lone Star” © 2005 by Kimberly Sultze. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hollywood’s West : The American frontier in film, television, and history / edited by Peter C. Rollins and John E. O'Connor. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8131-2354-2 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Western films—United States—History and criticism. 2. Western television programs—United States. I. O'Connor, John E. II. Rollins, Peter C. PN1995.9.W4A44 2005 791.436'278--dc22 2005018026 This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

Film Music and Film Genre

Film Music and Film Genre Mark Brownrigg A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Stirling April 2003 FILM MUSIC AND FILM GENRE CONTENTS Page Abstract Acknowledgments 11 Chapter One: IntroductionIntroduction, Literature Review and Methodology 1 LiteratureFilm Review Music and Genre 3 MethodologyGenre and Film Music 15 10 Chapter Two: Film Music: Form and Function TheIntroduction Link with Romanticism 22 24 The Silent Film and Beyond 26 FilmTheConclusion Function Music of Film Form Music 3733 29 Chapter Three: IntroductionFilm Music and Film Genre 38 FilmProblems and of Genre Classification Theory 4341 FilmAltman Music and Genre and GenreTheory 4945 ConclusionOpening Titles and Generic Location 61 52 Chapter Four: IntroductionMusic and the Western 62 The Western and American Identity: the Influence of Aaron Copland 63 Folk Music, Religious Music and Popular Song 66 The SingingWest Cowboy, the Guitar and other Instruments 73 Evocative of the "Indian""Westering" Music 7977 CavalryNative and American Civil War WesternsMusic 84 86 PastoralDown andMexico Family Westerns Way 89 90 Chapter Four contd.: The Spaghetti Western 95 "Revisionist" Westerns 99 The "Post - Western" 103 "Modern-Day" Westerns 107 Impact on Films in other Genres 110 Conclusion 111 Chapter Five: Music and the Horror Film Introduction 112 Tonality/Atonality 115 An Assault on Pitch 118 Regular Use of Discord 119 Fragmentation 121 Chromaticism 122 The A voidance of Melody 123 Tessitura in extremis and Unorthodox Playing Techniques 124 Pedal Point