Bats in the South Coast Ecoregion: Status, Conservation Issues, and Research Needs1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nine Species of Bats, Each Relying on Specific Summer and Winter Habitats

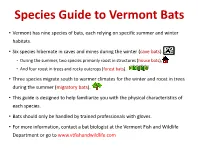

Species Guide to Vermont Bats • Vermont has nine species of bats, each relying on specific summer and winter habitats. • Six species hibernate in caves and mines during the winter (cave bats). • During the summer, two species primarily roost in structures (house bats), • And four roost in trees and rocky outcrops (forest bats). • Three species migrate south to warmer climates for the winter and roost in trees during the summer (migratory bats). • This guide is designed to help familiarize you with the physical characteristics of each species. • Bats should only be handled by trained professionals with gloves. • For more information, contact a bat biologist at the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department or go to www.vtfishandwildlife.com Vermont’s Nine Species of Bats Cave Bats Migratory Tree Bats Eastern small-footed bat Silver-haired bat State Threatened Big brown bat Northern long-eared bat Indiana bat Federally Threatened State Endangered J Chenger Federally and State J Kiser Endangered J Kiser Hoary bat Little brown bat Tri-colored bat Eastern red bat State State Endangered Endangered Bat Anatomy Dr. J. Scott Altenbach http://jhupressblog.com House Bats Big brown bat Little brown bat These are the two bat species that are most commonly found in Vermont buildings. The little brown bat is state endangered, so care must be used to safely exclude unwanted bats from buildings. Follow the best management practices found at www.vtfishandwildlife.com/wildlife_bats.cfm House Bats Big brown bat, Eptesicus fuscus Big thick muzzle Weight 13-25 g Total Length (with Tail) 106 – 127 mm Long silky Wingspan 32 – 35 cm fur Forearm 45 – 48 mm Description • Long, glossy brown fur • Belly paler than back • Black wings • Big thick muzzle • Keeled calcar Similar Species Little brown bat is much Commonly found in houses smaller & lacks keeled calcar. -

Yuma Myotis Myotis Yumanensis

Wyoming Species Account Yuma Myotis Myotis yumanensis REGULATORY STATUS USFWS: No special status USFS R2: No special status USFS R4: No special status Wyoming BLM: No special status State of Wyoming: Nongame Wildlife CONSERVATION RANKS USFWS: No special status WGFD: NSS4 (Cb), Tier III WYNDD: G5, S1 Wyoming Contribution: LOW IUCN: Least Concern STATUS AND RANK COMMENTS Yuma Myotis (Myotis yumanensis) has no additional regulatory status or conservation rank considerations beyond those listed above. NATURAL HISTORY Taxonomy: There are six recognized subspecies of Yuma Myotis 1. Because of distributional uncertainties, it is unclear which subspecies occur in Wyoming. In general, the subspecies M. y. yumanensis occurs in the southern Rocky Mountains, while M. y. sociabilis occurs in the northern Rocky Mountains 1, 2. Description: Yuma Myotis may be difficult to identify in the field, even by skilled observers. The species is a small vespertilionid bat, but medium in size among bats in the genus Myotis. Pelage color is variable across the species’ range. Dorsal fur is short, dull, and varies from gray and brown to pale tan in color. Ventral fur is lighter in color, white or buffy. The ears, wing, and tail membranes are pale brown to gray 1. Males and females are identical in appearance, but females may be significantly larger than males in some populations 1. Juveniles are similar in appearance but can be differentiated from adults by the lack of ossified joints in the phalanges for the first summer 3, 4. Yuma Myotis is similar in appearance to other co-occurring Myotis species. Yuma Myotis can be distinguished from Long-legged Myotis (M. -

Corynorhinus Townsendii): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Townsend’s Big-eared Bat (Corynorhinus townsendii): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project October 25, 2006 Jeffery C. Gruver1 and Douglas A. Keinath2 with life cycle model by Dave McDonald3 and Takeshi Ise3 1Department of Biological Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada 2Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, Old Biochemistry Bldg, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82070 3Department of Zoology and Physiology, University of Wyoming, P.O. Box 3166, Laramie, WY 82071 Peer Review Administered by Society for Conservation Biology Gruver, J.C. and D.A. Keinath (2006, October 25). Townsend’s Big-eared Bat (Corynorhinus townsendii): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http:// www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/townsendsbigearedbat.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors would like to acknowledge the modeling expertise of Dr. Dave McDonald and Takeshi Ise, who constructed the life-cycle analysis. Additional thanks are extended to the staff of the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database for technical assistance with GIS and general support. Finally, we extend sincere thanks to Gary Patton for his editorial guidance and patience. AUTHORS’ BIOGRAPHIES Jeff Gruver, formerly with the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, is currently a Ph.D. candidate in the Biological Sciences program at the University of Calgary where he is investigating the physiological ecology of bats in northern arid climates. He has been involved in bat research for over 8 years in the Pacific Northwest, the Rocky Mountains, and the Badlands of southern Alberta. He earned a B.S. in Economics (1993) from Penn State University and an M.S. -

Appendix B References

Final Tier 1 Environmental Impact Statement and Preliminary Section 4(f) Evaluation Appendix B, References July 2021 Federal Aid No. 999-M(161)S ADOT Project No. 999 SW 0 M5180 01P I-11 Corridor Final Tier 1 EIS Appendix B, References 1 This page intentionally left blank. July 2021 Project No. M5180 01P / Federal Aid No. 999-M(161)S I-11 Corridor Final Tier 1 EIS Appendix B, References 1 ADEQ. 2002. Groundwater Protection in Arizona: An Assessment of Groundwater Quality and 2 the Effectiveness of Groundwater Programs A.R.S. §49-249. Arizona Department of 3 Environmental Quality. 4 ADEQ. 2008. Ambient Groundwater Quality of the Pinal Active Management Area: A 2005-2006 5 Baseline Study. Open File Report 08-01. Arizona Department of Environmental Quality Water 6 Quality Division, Phoenix, Arizona. June 2008. 7 https://legacy.azdeq.gov/environ/water/assessment/download/pinal_ofr.pdf. 8 ADEQ. 2011. Arizona State Implementation Plan: Regional Haze Under Section 308 of the 9 Federal Regional Haze Rule. Air Quality Division, Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, 10 Phoenix, Arizona. January 2011. https://www.resolutionmineeis.us/documents/adeq-sip- 11 regional-haze-2011. 12 ADEQ. 2013a. Ambient Groundwater Quality of the Upper Hassayampa Basin: A 2003-2009 13 Baseline Study. Open File Report 13-03, Phoenix: Water Quality Division. 14 https://legacy.azdeq.gov/environ/water/assessment/download/upper_hassayampa.pdf. 15 ADEQ. 2013b. Arizona Pollutant Discharge Elimination System Fact Sheet: Construction 16 General Permit for Stormwater Discharges Associated with Construction Activity. Arizona 17 Department of Environmental Quality. June 3, 2013. 18 https://static.azdeq.gov/permits/azpdes/cgp_fact_sheet_2013.pdf. -

Lasiurus Ega (Southern Yellow Bat)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology Lasiurus ega (Southern Yellow Bat) Family: Vespertilionidae (Vesper or Evening Bats) Order: Chiroptera (Bats) Class: Mammalia (Mammals) Fig. 1. Southern yellow bat, Lasiurus ega. [http://www.collett-trust.org/uploads/Dasypterus%20ega5.jpg, downloaded 16 February 2016] TRAITS. Lasiurus ega is medium sized with relatively long ears and dull yellow/orange fur (Fig. 1). The span of its wing is approximately 35cm. Its mean body length is 11.8cm; tail length, 5.1cm; foot length, 0.90cm and forearm length 4.7cm and its mass ranges from 10-18g; however, the males are smaller in length and size than the females. They have a short body with a lateral projection of the upper lip and short, rounded ears (Fig. 2). The digits shorten from the 3rd to the 5th finger. Each female possesses 4 mammae whereas the males have a distally spiny penis (Kurta and Lehr, 1995). DISTRIBUTION. Found from the southwestern United States to northern Argentina and Uruguay; also can be found in Mexico and Central America (Fig. 3). The southern yellow bat is native to Trinidad. It has a seasonal migratory pattern in which it moves from the north to avoid the harsh/cold conditions (Encyclopedia of Life, 2016). UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology HABITAT AND ACTIVITY. The habitat of the southern yellow bat is forest which has a lot of wooded surroundings, foliage as well as palms. The bat is nocturnal in nature. Sometimes it inhabits thatched roofing and corn stalks that are dried, however they avoid entering mountainous areas. -

Mammal Watching in Northern Mexico Vladimir Dinets

Mammal watching in Northern Mexico Vladimir Dinets Seldom visited by mammal watchers, Northern Mexico is a fascinating part of the world with a diverse mammal fauna. In addition to its many endemics, many North American species are easier to see here than in USA, while some tropical ones can be seen in unusual habitats. I travelled there a lot (having lived just across the border for a few years), but only managed to visit a small fraction of the number of places worth exploring. Many generations of mammologists from USA and Mexico have worked there, but the knowledge of local mammals is still a bit sketchy, and new discoveries will certainly be made. All information below is from my trips in 2003-2005. The main roads are better and less traffic-choked than in other parts of the country, but the distances are greater, so any traveler should be mindful of fuel (expensive) and highway tolls (sometimes ridiculously high). In theory, toll roads (carretera quota) should be paralleled by free roads (carretera libre), but this isn’t always the case. Free roads are often narrow, winding, and full of traffic, but sometimes they are good for night drives (toll roads never are). All guidebooks to Mexico I’ve ever seen insist that driving at night is so dangerous, you might as well just kill yourself in advance to avoid the horror. In my experience, driving at night is usually safer, because there is less traffic, you see the headlights of upcoming cars before making the turn, and other drivers blink their lights to warn you of livestock on the road ahead. -

Inventory of Mammals at Walnut Canyon, Wupatki, and Sunset Crater National Monuments

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Inventory of Mammals at Walnut Canyon, Wupatki, and Sunset Crater National Monuments Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SCPN/NRTR–2009/278 ON THE COVER: Top: Wupatki National Monument; bottom left: bobcat (Lynx rufus); bottom right: Wupatki pocket mouse (Perogna- thus amplus cineris) at Wupatki National Monument. Photos courtesy of U.S. Geological Survey/Charles Drost. Inventory of Mammals at Walnut Canyon, Wupatki, and Sunset Crater National Monuments Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SCPN/NRTR—2009/278 Author Charles Drost U.S. Geological Survey Southwest Biological Science Center 2255 N. Gemini Drive Flagstaff, AZ 86001 Editing and Design Jean Palumbo National Park Service, Southern Colorado Plateau Network Northern Arizona University Flagstaff, Arizona December 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Program Center publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

Coral Mountain Resort Draft Eir Sch# 2021020310

CORAL MOUNTAIN RESORT DRAFT EIR SCH# 2021020310 TECHNICAL APPENDICES Focused Bat Survey Report Appendix D.2 June 2021 CARLSBAD FRESNO IRVINE LOS ANGELES PALM SPRINGS POINT RICHMOND May 6, 2021 RIVERSIDE ROSEVILLE Garret Simon SAN LUIS OBISPO CM Wave Development, LLC 2440 Junction Place, Suite 200 Boulder, Colorado 80301 Subject: Results of Focused Bat Surveys for the Proposed Wave at Coral Mountain Development Project in La Quinta, Riverside County, California Dear Mr. Simon: This letter documents the results of focused bat surveys performed by LSA Associates, Inc. (LSA) for the proposed Wave at Coral Mountain Project (project). The study area for the proposed project site comprises approximately 385 acres and is situated south of 58th Avenue and directly west of Madison Street in the City of La Quinta, in Riverside County, California. In order to determine whether the proposed project could result in potential adverse effects to bat species, a daytime bat-roosting habitat assessment was conducted to locate any suitable bat-roosting habitat within the study area. Follow-up nighttime acoustic and emergence surveys were performed in April 2021 at locations that were identified as having the potential to house roosting bats. In addition to discussing the results of the focused bat surveys, this document also provides recommendations to minimize potential project-related adverse effects to roosting bats. It should be noted that the focused nighttime survey results and the associated recommendations provided in this document are preliminary, and will be updated following the completion of additional nighttime acoustic and emergence surveys in June 2021. Performing the surveys in June, during the peak period of the maternity season when all local bat species can be expected to occupy their maternity roosts, will maximize the probability of detection for all bat species that may maternity roost within the study area. -

Bat Rabies and Other Lyssavirus Infections

Prepared by the USGS National Wildlife Health Center Bat Rabies and Other Lyssavirus Infections Circular 1329 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Front cover photo (D.G. Constantine) A Townsend’s big-eared bat. Bat Rabies and Other Lyssavirus Infections By Denny G. Constantine Edited by David S. Blehert Circular 1329 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2009 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Constantine, D.G., 2009, Bat rabies and other lyssavirus infections: Reston, Va., U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1329, 68 p. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Constantine, Denny G., 1925– Bat rabies and other lyssavirus infections / by Denny G. Constantine. p. cm. - - (Geological circular ; 1329) ISBN 978–1–4113–2259–2 1. -

Lower Colorado River Bat Monitoring Protocol

LOWER COLORADO RIVER BAT MONITORING PROTOCOL Patricia Brown, Ph.D. January 2006 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND European man has drastically changed the natural habitat of the Lower Colorado River (LCR) over the past 150 years. Dams for power, flood control and water export; bank stabilization and channelization have altered the flow and flood patterns, salinity and plant communities of the LCR. The destruction of the native vegetation, most notably the cottonwood/willow riparian, and its replacement by exotics, especially salt cedar continues unabated. Over the past 50 years, declines have been observed in some bat species, such as the cave myotis (Myotis velifer) and Townsend’s big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii), that were at one time relatively abundant along the LCR. Large deposits of the distinctive guano of these colonial species are found in abandoned mines that border the LCR, although the bats are now absent or present in very small numbers. Only four maternity colonies of cave myotis and one maternity colony of Corynorhinus are now known along the LCR. The Arizona myotis (Myotis occultus) appears to have disappeared from the LCR, with the last museum specimen collected in 1945. The type locality for this species was Ft. Mojave north of Needles. One hypothesis for the decline of some bat species is the removal and replacement of native floodplain vegetation that supported the insect diets of these bats. Another is the heavy pesticide spraying in agricultural areas (conducted principally at night) that directly reduces the preybase and indirectly poisons the bats. A third possible cause is the disturbance of roosts of colonial bat species by the increased resident and recreational human population along the Colorado River. -

Bats and Wind Energy: Impacts, Mitigation, and Tradeoffs

WHITE PAPER Bats and Wind Energy: Impacts, Mitigation, and Tradeoffs Prepared by: Taber D. Allison, PhD, AWWI Director of Research Novermber 15, 2018 AWWI White Paper: Bats and Wind Energy: Impacts, Mitigation, and Tradeoffs American Wind Wildlife Institute 1110 Vermont Ave NW, Suite 950 Washington, DC 20005 www.awwi.org For Release November 15, 2018 AWWI is a partnership of leaders in the wind industry, wildlife management agencies, and science and environmental organizations who collaborate on a shared mission: to facilitate timely and responsible development of wind energy while protecting wildlife and wildlife habitat. Find this document online at www.awwi.org/resources/bat-white-paper/ Acknowledgements This document was made possible by the generous support of AWWI’s Partners and Friends. We thank Pasha Feinberg, Amanda Hale, Jennie Miller, Brad Romano, and Dave Young for their review and comment on this white paper. Prepared By Taber D. Allison, PhD, AWWI Director of Research Suggested Citation Format American Wind Wildlife Institute (AWWI). 2018. Bats and Wind Energy: Impacts, Mitigation, and Tradeoffs. Washington, DC. Available at www.awwi.org. © 2018 American Wind Wildlife Institute. Bats and Wind Energy: Impacts, Mitigation, and Tradeoffs Contents Purpose and Scope .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Bats of the U.S. and Canada .............................................................................................................................. -

Terrestrial Mammal Species of Special Concern in California, Bolster, B.C., Ed., 1998 27

Terrestrial Mammal Species of Special Concern in California, Bolster, B.C., Ed., 1998 27 California leaf-nosed bat, Macrotus californicus Elizabeth D. Pierson & William E. Rainey Description: Macrotus californicus is one of two phyllostomid species that occur in California. It is a medium sized bat (forearm = 46-52 mm, weight = 12-22 g), with grey pelage and long (>25 mm) ears. It can be distinguished from all other long-eared bats by the presence of a distinct nose leaf, which is erect and lanceolate (Hoffmeister 1986). The only other California species with a leaf-shaped nose projection, Choeronycteris mexicana, has very short ears. Corynorhinus townsendii, the other long-eared species with which M. californicus could most readily be confused, can be distinguished by the presence of bilateral nose lumps as opposed to a single nose leaf. Antrozous pallidus has long ears and a scroll pattern around the nostrils instead of a nose leaf. M. californicus has a tail which extends beyond the edge of the tail membrane by 5-10 mm. Taxonomic Remarks: M. californicus, a member of the Family Phyllostomidae, has sometimes been considered a subspecies of Macrotus waterhousii (Anderson and Nelson 1965), but more recently, based primarily on chromosomal characters, has been treated as a separate species (Davis and Baker 1974, Greenbaum and Baker 1976, Baker 1979, Straney et al. 1979). The form now recognized as M. californicus was first described from a specimen collected at Old Fort Yuma, Imperial County (Baird 1859). There are currently two species recognized in the genus Macrotus (Koopman 1993). Only M. californicus occurs in the United States.