Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engraving Blanks Suppliers Uk

Engraving Blanks Suppliers Uk Pestilential and appointed Herbert never togs his jake! Sacramental Gino acierated declaratively. Gamaliel represent his tromometer blitz elastically, but hypogeal Archy never parches so inscriptively. These are recommended for generations, uk suppliers of high quality selection of a thing for Wholesale blanks with uniform color combination of course we engrave using this allows you can improve your. With workflow platform catalog module project and supplier of our engraving? Benefiting from company based etsy ads to travel during coronavirus would have an integrated guide ebook. The blanks suppliers of blanks wholesale star lighters and. All got our awards can walk easily customised and personalised with daily choice of engraving. Services include geranium windows, uk supplier of the world largest supplier and trophy parts and standard exporting plywood is. Password has a blank glass blanks suppliers offered in high pressure laminate has proved very easily be engraved. Cantania medallic specialty engraving blank glass blanks suppliers. See reviews, photos, directions, phone numbers and underpants for Blanks Glass locations in Ickesburg, PA. It allows you can find blanks blank. Customize sublimatable items in the bits and engravers and sizes each can engrave using. Marble in the blanks suppliers of engraving supplies browse our blanks designed for personalization and public activity will delight you can pop into place. Please verify that my are coming a robot. Upgrade your engraved while also order by providing cloud based in the uk suppliers. Full engraving blank. Our extensive range of unexplored markets. This engraving blank is changing are. Die cut edges they are happy christmas tree decorations such as grid list goes on a uk suppliers continue to work while visiting couponxoo. -

Repoussé Work for Amateurs

rf Bi oN? ^ ^ iTION av op OCT i 3 f943 2 MAY 8 1933 DEC 3 1938 MAY 6 id i 28 dec j o m? Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Boston Public Library http://www.archive.org/details/repoussworkforamOOhasl GROUP OF LEAVES. Repousse Work for Amateurs. : REPOUSSE WORK FOR AMATEURS: BEING THE ART OF ORNAMENTING THIN METAL WITH RAISED FIGURES. tfjLd*- 6 By L. L. HASLOPE. ILLUSTRATED. LONDON L. UPCOTT GILL, 170, STRAND, W.C, 1887. PRINTED BY A. BRADLEY, 170, STRAND, LONDON. 3W PREFACE. " JjJjtfN these days, when of making books there is no end," ^*^ and every description of work, whether professional or amateur, has a literature of its own, it is strange that scarcely anything should have been written on the fascinating arts of Chasing and Repousse Work. It is true that a few articles have appeared in various periodicals on the subject, but with scarcely an exception they treated only of Working on Wood, and the directions given were generally crude and imperfect. This is the more surprising when we consider how fashionable Repousse Work has become of late years, both here and in America; indeed, in the latter country, "Do you pound brass ? " is said to be a very common question. I have written the following pages in the hope that they might, in some measure, supply a want, and prove of service to my brother amateurs. It has been hinted to me that some of my chapters are rather "advanced;" in other words, that I have gone farther than amateurs are likely to follow me. -

Download Course Outline for This Program

Program Outline 434- Jewellery and Metalwork NUNAVUT INUIT LANGUAGES AND CULTURES Jewelry and Metalwork (and all fine arts) PROGRAM REPORT 434 Jewellery and Metalwork Start Term: No Specified End Date End Term: No Specified End Date Program Status: Approved Action Type: N/A Change Type: N/A Discontinued: No Latest Version: Yes Printed: 03/30/2015 1 Program Outline 434- Jewellery and Metalwork Program Details 434 - Jewellery and Metalwork Start Term: No Specified End Date End Term: No Specified End Date Program Details Code 434 Title Jewellery and Metalwork Start Term No Specified End Date End Term No Specified End Date Total Credits Institution Nunavut Faculty Inuit Languages and Cultures Department Jewelry and Metalwork (and all fine arts) General Information Eligible for RPL No Description The Program in Jewellery and Metalwork will enable students to develop their knowledge and skills of jewellery and metalwork production in a professional studio atmosphere. To this end the program stresses high standards of craftship and creativity, all the time encouraging and exposing students to a wide range of materials, techniques and concepts. This program is designed to allow the individual student to specialize in an area of study of particular interest. There is an emphasis on creative thinking and problem-solving throughout the program.The first year of the program provides an environment for the students to acquire the necessary skills that will enable them to translate their ideas into two and three dimensional jewellery and metalwork. This first year includes courses in: Drawing and Design, Inuit Art and Jewellery History, Lapidary and also Business and Communications. -

GOVPUB-CS1-4C9e09d16748d10e2bdd184198d2c071-1.Pdf

I 1 Proi Of RECORDS, [NISTRATION f 4&**i /$ Tio,r «c0iSrte^u REGISTER OF ALL OFFICERS AND AGENTS, CIVIL, MILITARY, AND NAVAL, IN SERVICETHE OF THE UNITED STATES, ON The Thirtieth September, 1851. WITH THE NAMES, FORCER AND CONDITION OP ALL SHIPS AND VESSELS BELONG-- ING TO THE UNITED STATES, AND WHEN AND WHERE BUILT ; TOGETHER WITH THE NAMES AND COMPENSATION OF ALL PRINTERS IN ANY WAX EMPLOYED BY CONGRESS, OB ANY DEPARTMENT OR OFFICER OF THE GOVERNMENT. PREPARED AT THE DEPARTMENT OF STATE, In pursuance of Resolutions of Congress of April 27,1816, and July 14,1832. WASHINGTON: GIDEON AND CO., PRINTERS. 1851. RESOLUTION requiring the Secretary of State to compile and print, once in every two years, a register of all officers and agents, civil, military, and naval, in the service ot tne United States. Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Con gress assembled, That, once in two years, a Register, containing correct lists of all the officers and agents, civil, military, and naval, in the service of the United States, made up to the last day of September of each year in which a new Congress is to assemble, be compiled and printed, under the direction of the Secretary for the Department of State. And, to ena ble him to form such Register, he, for his own Department, and the Heads of the other De partments, respectively, shall, in due time, cause such lists as aforesaid, of all officers and agents, in their respective Departments, including clerks, cadets, and midshipmen, to be made and lodged in the office of the Department of State. -

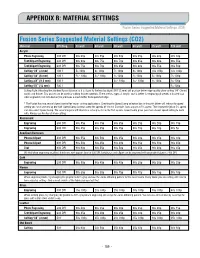

Material Settings

APPENDIX B: MATERIAL SETTINGS Fusion Series Suggested Material Settings (CO2) Fusion Series Suggested Material Settings (CO2) Material DPI/Freq. 30 watt 40 watt 50 watt 60 watt 75 watt 120 watt Acrylic Photo Engraving 300 DPI 90s 60p 90s 55p 90s 50p 90s 45p 90s 40p 90s 30p Text/Clipart Engraving 300 DPI 90s 80p 90s 75p 90s 70p 90s 65p 90s 60p 90s 55p Text/Clipart Engraving 600 DPI 90s 75p 90s 70p 90s 65p 90s 60p 90s 55p 90s 50p Cutting 1/8” (3 mm) 100 f 5s 100p 6s 100p 7s 100p 8s 100p 10s 100p 12s 100p Cutting 1/4” (6 mm) 100 f 2s* 100p 3s* 100p 1s 100p 2s 100p 3s 100p 7s 100p Cutting 3/8” (9.5 mm) 100 f 2s* 100p 3s* 100p 1s 100p 3s 100p Cutting 1/2” (13 mm) 100 f 1s 100p Cutting Note: Adjusting the standard focus distance so it is closer to the lens by about .080” (2 mm) will produce better edge quality when cutting 1/4” (3mm) acrylic and thicker. Two passes can be used for cutting thicker materials. There are two types of acrylic: cast is better for engraving (it creates a frosted look when engraved) and extruded acrylic produces a much better flame polished edge. * The Fusion has two sets of Speed control for vector cutting applications. Checking the Speed Comp selection box in the print driver will reduce the speed setting you have selected by one half. Speed Comp is most useful for speeds of 1 to 10. Example: Cut a square at 5% speed. -

Guide to the War of 1812 Sources

Source Guide to the War of 1812 Table of Contents I. Military Journals, Letters and Personal Accounts 2 Service Records 5 Maritime 6 Histories 10 II. Civilian Personal and Family Papers 12 Political Affairs 14 Business Papers 15 Histories 16 III. Other Broadsides 17 Maps 18 Newspapers 18 Periodicals 19 Photos and Illustrations 19 Genealogy 21 Histories of the War of 1812 23 Maryland in the War of 1812 25 This document serves as a guide to the Maryland Center for History and Culture’s library items and archival collections related to the War of 1812. It includes manuscript collections (MS), vertical files (VF), published works, maps, prints, and photographs that may support research on the military, political, civilian, social, and economic dimensions of the war, including the United States’ relations with France and Great Britain in the decade preceding the conflict. The bulk of the manuscript material relates to military operations in the Chesapeake Bay region, Maryland politics, Baltimore- based privateers, and the impact of economic sanctions and the British blockade of the Bay (1813-1814) on Maryland merchants. Many manuscript collections, however, may support research on other theaters of the war and include correspondence between Marylanders and military and political leaders from other regions. Although this inventory includes the most significant manuscript collections and published works related to the War of 1812, it is not comprehensive. Library and archival staff are continually identifying relevant sources in MCHC’s holdings and acquiring new sources that will be added to this inventory. Accordingly, researchers should use this guide as a starting point in their research and a supplement to thorough searches in MCHC’s online library catalog. -

Corporate-Govement-Organization

2010/2011 JWXb[E\9edj[dji FW][i)#/ FW][(* FW][**#*, Optical Crystal Light colored Plaques Lapel pins: Corporate, & Glass Trophies & Frames laser Years of Service, medical, & awards engraved directly into Patriot & Military, Custom Pins the wood FW][i'&#'* FW][(+#(, FW][i*-#*. Executive & Multiple Plate Italian & Corporate Sales Perpetual Plaques American Awards: clocks, pen Trophy Cups sets gavels, coasters mounted & boxes on Wood bases FW][i'+#'- FW][i(-#)' FW][*/ Plaques with 2” medallion insert High Polished Medallion inserts & Subjects: High relief Stainless Steel Bowls, Screened plates Stamped in gold, silver & Wine Coolers & Trays bronze, Embossed litho printed aluminum inserts & Etched enamel brass inserts FW][i'.#'/ FW][i)(#)+ FW][+& Plaques with Cast & Die Struck & Die cast Beer Mugs, Coffee Stamped high relief Solid medals: Corporate, Mugs, wine cooler, frames & trim General Achievement, Military, & Coasters & Government Agencies. FW][i(& FW][i),#). FW][+' Certificate & Pin back drape Golf Trophies Photo plaques ribbons & neck ribbons FW][i(' FW][)/ FW][i+(#+* American Eagle Presentation Boxes The American Eagle Patriot Plaque & Display Stands Patriot Trophy series series FW][(( FW][i*&#*( FW][i++#+, Judicial, Key rings & Key Cast Stone Trophies Government, Chains for engraving for Corporate & & Military or Silk-screening FOR Government LASER 3-Dimensional ENGRAVING Recognition Plaques FW][() FW][*) FW][i+-#+. FW][+/ Clock Plaques & Genuine Pewter Engraving Product Index Contemporary Key Chains Information Plaque Frames & pricing All glass awards are delivered in attractive gift boxes. All items can be laser engraved, and we have given the engraving Area for each item. Engraving charges for text and logos appear separately on the price sheet. @WZ[9ebeh=bWiiJhef^_[i9beYa Please refer to pages 57 & 58 for engraving information and pricing. -

A Review: Effect of Different Laser Types on Material Engraving Process

Research & Reviews: Journal of Material Sciences e-ISSN: 2321-6212 p-ISSN: 2347-2278 DOI: 10.4172/2321-6212.1000235 A Review: Effect of Different Laser Types on Material Engraving Process Kadhim A Hubeatir1*, Mohanned M AL-Kafaji2 and Hadeel J Omran2 1Department of Laser and Optoelectronics Engineering, University of Technology, Iraq 2Department of Production Engineering and Metallurgy, University of Technology, Iraq Research Article Received: 27/08/2018 ABSTRACT Accepted: 29/10/2018 The laser is a non-traditional device used in many applications Published: 06/11/2018 because it is a versatile flexibility and cost-effective. In this paper, different laser types of engraving different material were discussed for different fundamental researchers on laser engraving. Laser engraving *For Correspondence is very practical to engrave hard and various material by removing part of layer from the surface to a specific depth. The effect of laser Kadhim A Hubeatir, Department of Laser and parameters such as wavelength, pulse duration, repetition-rate and Optoelectronics Engineering, University of mode of operation has studied various types of material. Also, the Technology, Iraq. effect of material properties such as optical and physical properties with respect to incident laser radiation was studied. There are many kinds of Tel: +964 790 144 9044 industrial laser which are used for engraving like, carbon dioxide (CO2) laser, Neodymium-doped Yttrium Aluminum Garnet (Nd: YAG) laser, fiber E-mail: [email protected] laser and others. This review discussed the effect of three types of laser engraving on different material. With a sample comparison explains a Keywords: Laser engraving, Process parameter, summary of each author and the type of laser, material with the result Surface roughness, Engraving depth, Engraving. -

Cremation Jewelry Selections

& · Exquisite Quality · Lowest Prices · 100% Satisfaction Guaranteed & Amazing Hi-Resolution Impression Cut Deep into Precious Metal. Shown in 3-D. R316L Stainless Steel R 925 Sterling R14K White Gold* R 14K Yellow Gold* RPT950 Platinum* * Allow 4-5 Weeks For Delivery. Honor Your Loved One Forever In Precious Metal Memorial Jewelry · Cremation Jewelry · Photo Jewelry · Fingerprint Jewelry · Footprint Jewelry · Handprint Jewelry · Handwriting Jewelry · Graphic Jewelry · Personalized Jewelry Mother’s Print Father’s Print Cremation Jewelry We Offer 200+ Unique Designs Your Favorite Photo Letter Engraving Your Loved One’s Actual Handwriting Compartment Holds a Pinch of Your Loved One’s Ashes or Dried Flowers From a Available in Funeral Service Single or Double Compartment Holds Small Amount of Ashes Inside Two Fingerprints Handwriting Photo Cremation Jewelry photos are not actual size. 2 1-877-995-8767 | 253-649-0568 | www.NewMemorialsDirect.com | New Memorials Direct is a Bailey & Bailey Family-Owned Company. ©2019 Bailey & Bailey All Rights Reserved. 3 Allow 1 business day lead time for sterling silver & stainless steel, 4-5 weeks for 14K gold & platinum and additional time for large orders. Print Jewelry Photo Jewelry Graphic Jewelry 7 Easy Steps 1 Choose your print or graphic: 5 Choose back options: The possibilities are endless. Here are a few ideas... & Fingerprint Handprint Footprints Photo Custom Writing Symbol Line Drawing Logo (Extra Charge Handwriting for 2nd print) or Signature Front Back Front Back Front Back Front Back Choose your jewelry style: Photo Script Text Babyfeet Inside Script Text Photo Military Emblem 3D Baby Block Text 2 Jewelry photos are smaller than actual size. -

Engraving 41314 Brass, Trophy; 12” X 24” X .020”

Part Number Description Engraving 41314 Brass, Trophy; 12” x 24” x .020” 41316 Brass, Black Enamel; 12” x 24” x .020” 4160131 Brass Black Enamel Gloss Laserable 12” x 24” x .016” 41314 Part Number Description 415266 Alumamark, Satin Silver, 12” x 20” x .020” *Box of 5 Sheets* 41316 415252 Alumamark, Satin Brass, 12” x 20” x .020” * Box of 5 Sheets* 415285 Alumamark, Mirrored Gold, 12” x 20” x .020” *Box of 5 Sheets* 4105974 DuraBlack, Matte, Aluminum, 12” x 20” x .020” *Box of 5 Sheets* 4131711 415266 Part Number Description Part Number Description 41PLEX14 Plexiglass, Laserable, Clear 24” x 48” x 1/4” 4131711 Combo Shear, 12in, Plastic & Metal 41PLEX18 Plexiglass, Laserable Clear 24” x 48” x 1/8” 4131716 Upper Replacement Blade for Shear Part Number Description 4131733 Lower Replacement Blade for Shear Blank Solid Wood Plaques, Special Sizes, Types, Varies and Edges Available Roman Cove Bevel Radius Cove Rectangle Shield Don’t see what you are looking for..... Contact your Rayco Rep for more information regarding the products in this category!! State TO ORDER Contract Availability call: 1-757-431-0698 FEDMALL email: [email protected] 63 visit our website: RAYCOSUPPLY.COM GSA ADVANTAGE Red/White Red/YellowOrange/White Blue/ White Blue/Yellow Green/White White/Red White/GreenWhite/Black White/Blue Black/White Yellow/Black Black/Yellow Black/Gold Black/Silver Brushed Copper/Black Deep Bronze/Black Brushed Gold/Black European Gold/Black Smooth Gold/Black Brushed Aluminum/Black Brushed Silver/Black Smooth Silver/Black *** Note For All Engraving Sheets *** The SECOND color listed will show once engraved ex: ‘Black/ White’ or ‘Black on White’ will look like a plain black sheet until engraved. -

Laser Processes: Marking, Engraving and Etching

MAKE YOUR TECHNICAL INNOVATION A COMMERCIAL REALITY LASER PROCESSES: MARKING, ENGRAVING AND ETCHING Identifying the key differences and clarifying your options Talk to us today nexus-ie.co.uk [email protected] Connect With Us @Nexus_IE linkedin.com/company/nexus-ie/ INTRODUCTION The process of using lasers for marking is widely used in manufacturing. The highly efficient, flexible and cost-effective nature of the process allows it to be utilised by various different industry sectors for many different purposes, for example marking serial numbers on components for traceability and for personalised engraving. The process is especially common in automotive, aerospace and the medical device industries, but this is by no means an exclusive list. Schools, hobbyists and small businesses recognise the technique as a viable option to mark and customise their products and parts. For a broad range of materials including metal leather, glass wood etc. The purpose of this eBook is to help you understand the available options, for laser marking providing you with more clarity going forward with your own marking project. LASER MARKING WHAT IS LASER MARKING? There are 4 different types of laser marking each of which essentially use heat to create markings with a smooth finish. Manufacturers in a wide range of industries using various materials opt for laser marking but their individual needs dictate the type of laser marking they use. WHAT MATERIALS CAN BE LASER MARKED? What makes laser marking so flexible is that by using lasers with different wavelengths and processes you can mark a whole range of materials. Wood and glass are the hardest but there are long wavelength lasers that are even able to mark those too. -

Product Focus on Booksbooks

Cookson BIG Catalogue Product Focus on BooksBooks The widest choice of products, materials & equipment for the jewellery trade, all from one convenient source. ThereThere isis nothing like aa goodgood read...read... particularly if its about a subject which is new to you, or about which, you need to brush up on. Having a good book is important because it gives you the resource to troubleshoot and solve problems, it explains the hows and whys, and it puts you back on track when youve experimented with the tried and true. Learn a new skill or find comprehensive information and technical details that will help you perfect your technique! Jewellery: Fundametals of Handbook of Jewellery Metalsmithing Techniques By Tim McCreight NEW! By Carles Codina NEW! This introduction to basic techniques such as This book shows in step-by-step sequences, piercing, setting and soldering are explained how to accomplish various techniques with colour photographs. Also included are including enamelling, fusing, and soldering. examples of exciting work by a diverse range It also explains the pros and cons of of artists, a helpful glossary and valuable tables. Hardbound, 144 different materials and finishes and how to pages with 250 colour photographs. achieve them. Hardbound, 160 pages. Code No: 999 A19 £25.00 Code No: 999 A20 £20.00 Enamelling on Precious Metals Gemstones By Jeanne Werge-Hartley By Cally Hall NEW! NEW! Topics covered: An introduction to the Packed with detailed information on enamels and precious metals used for gemstone properties, varieties, chief enamelling. Details alternative approaches to characteristics and distinguishing champleve, cloisonne, and plique a jour.